Editor’s Note: We offer a fine article by a new Lady of the West author, Artemisia Gentileschi. She is a long time friend to us, and we know you will enjoy (and benefit from) her thoughts.

It would seem that science is in the news a lot. People often share “I F***ing Love Science” memes (or the tamer version without the expletive) on Facebook. Various disciplines make the news almost daily. But I wonder if the people who share the memes and preach homage to scientists really “f***ing love science”? Do they love it enough to know its history? To know the source and inspiration for modern science as we know it? To converse with most people, I would answer no. They don’t love science. They “love” science, as long as it serves them and serves to strengthen a narrative. Further, I don’t know that they even truly understand science, the practice.

As Bernard of Chartres, and later Isaac Newton, said, “we are like dwarves perched on the shoulders of giants”. They were following in the footsteps of the Ancients, building upon their knowledge. Just as they learned from the Ancients, like Aristotle and Ptolemy, we have learned from them and others like them. But what drove them? What was their motivation to explore? To learn? To discover more about this world?

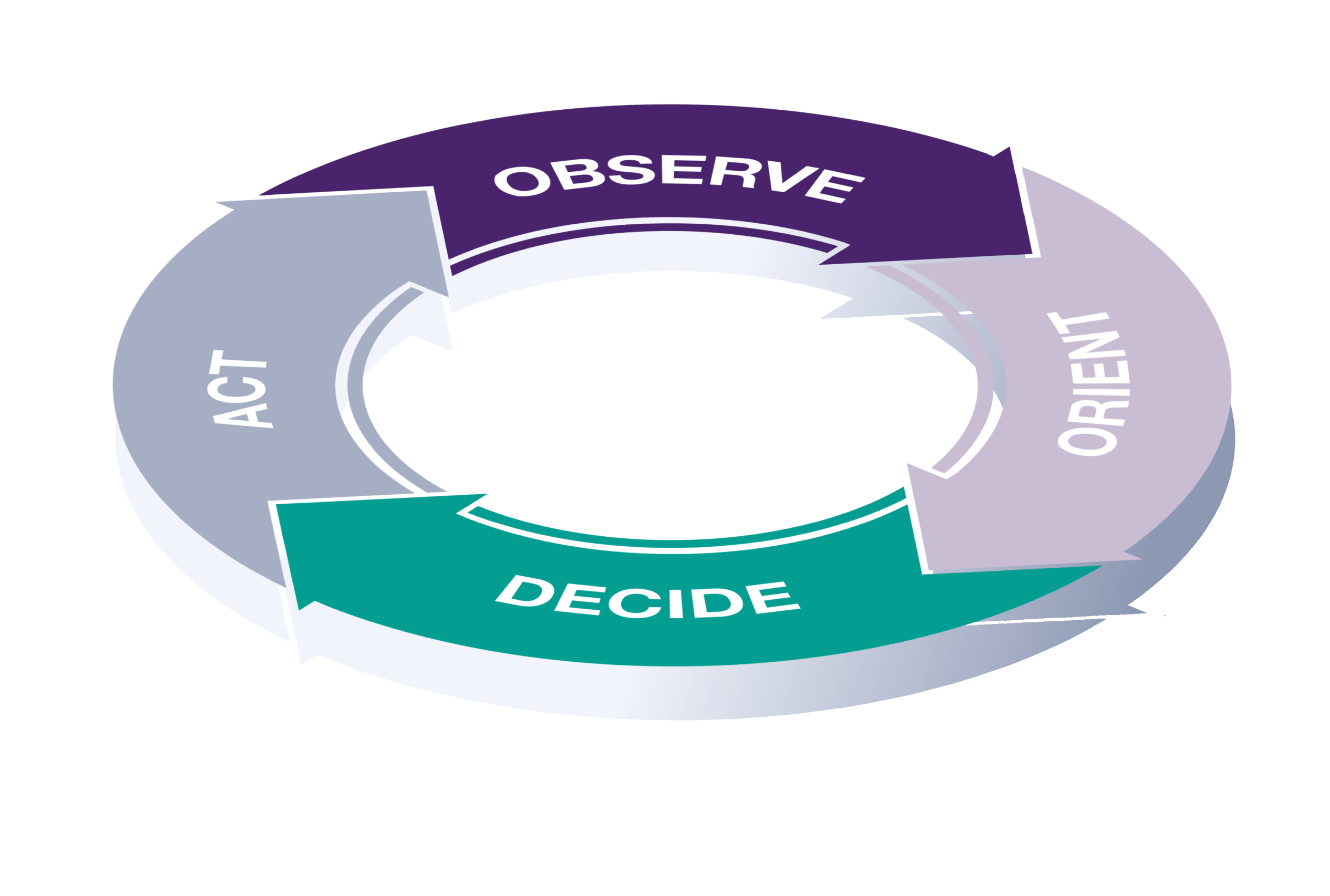

Though the Greeks brought us deductive reasoning, and the Romans excelled at applied science like architecture and engineering, the modern era of science is generally thought to begin with Francis Bacon, who formalized the scientific method as it is practiced today: a falsifiable hypothesis, experimentation and observation, followed by conclusion, whether the hypothesis has been confirmed or apply further refining of the hypothesis and more testing and observation if necessary. The fathers of modern science were not only scientists, but also philosophers and theologians. There is a great benefit in knowing philosophy, as well as science, because there are limits to science, and those knowledgeable in both areas of study can better recognize shortcomings of each process in the quest for knowledge.

The fathers of modern science were not just scientists and philosophers, they were also men of faith. To them there was no divide, no conflict, no battle between science and faith. Rather, their desire to know more about God and the world God made is what drove them in their search for knowledge. The history of science – and the history of the West – is rich with characters. Read more about them. The likes of Newton, Bacon, Mendel, Kepler, Da Vinci, Linnaeus, Faraday, Pasteur are the most well known, but many others made great contributions in various areas of science. Others worth reading about include Blaise Pascal (perhaps best known for his Wager and mathematics), Robert Boyle (chemistry), Athanasius Kircher (partially deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphics, germ theory of disease), Isaac Barrow (taught math to Newton), John Woodward (geologist), William Herschel (astronomy), Jean Deluc (geology and meteorology), James Parkinson (medicine), Humphrey Davy (chemistry), Benjamin Silliman (mineralogist, geologist, founded the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale and the American Journal of Science), Charles Babbage (computers), James Joule (thermodynamics), Henri Fabre (entomology), William Thompson – Lord Kelvin (physics, mathematics, thermodynamics), Joseph Lister (antiseptic surgery), Joseph Maxwell (physics), and many others.

So go ahead. Read about some giants. Show science some love.

Latest from Culture

While Thanksgiving in its present form is a distinctively American holiday, it did not spring Minerva-like

It seemed to me that, having to speak tonight to soldiers, that I ought to speak

A Sherlock Holmes adventure starring Jeremy Brett and Edward Hardwicke.

There seems to be a culminating point not only in all human arts, but in the

This is a marvelous article, and a fine way to start your contributions here. When I read stuff like this, it does sadden me to realize how far we have come down from the lofty heights of the founders of many genres. Like science, like the founding of America. We have turned so far away from God, I hope that enough of us can turn back.

I look forward to reading more of your contributions AG. As somebody who finds a lot of this goes over her head, I love to read articles that can unlock a lot of mysteries for me. Thank you so very much.

Thank you for the kind words Susan. I am glad you enjoyed it and I have some more topics in mind for future articles. One thing I find fascinating about early scientists was how well rounded they were. They didn’t do just one thing. They might simultaneously be a clergyman and inventor who took time to write a monolog on the anatomy of insects, and later that evening enjoy a lively discussion about philosophy. They really were interesting characters.

In taking my own advice, I read up a little on Jean Henri Fabre and found this article and quote:

“It would be easier to tear the flesh from my bones than to rob me of my belief in God,” he said. ” After eighty-seven years of observation and reflection, I can not so much say that I believe in God as that I see Him. Without Him, I understand nothing: without Him all is darkness. My studies have both preserved and strengthened this faith in me, and have even increased it. All epochs have their hobbies, and the hobby of our own epoch is, in my opinion, atheism, which I regard as the influenza of the age.” Jean Henri Fabre

http://newspapers.bc.edu/cgi-bin/bostonsh?a=d&d=BOSTONSH19160701-01.2.26

Fabre wrote many books, including books for children, which I intended to check out. (As if my book want list wasn’t large enough…) 😀

Kind regards,

AG

A G, Excellent article and quote from Fabre, Also when you said “Their desire to know more about God and the world he made is what drove them in their search for knowledge.” That thought is especially relevant, as trying to know God brings one knowledge of his creation and all thats in it. Trying to gain knowledge for knowledges sake will not lead one to the source (Divine creator) of knowledge. Kind of puts “Seek ye first” in a whole new light.

5