Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The World’s Greatest Military Spies and Secret Service Agents, by George Barton (published 1917).

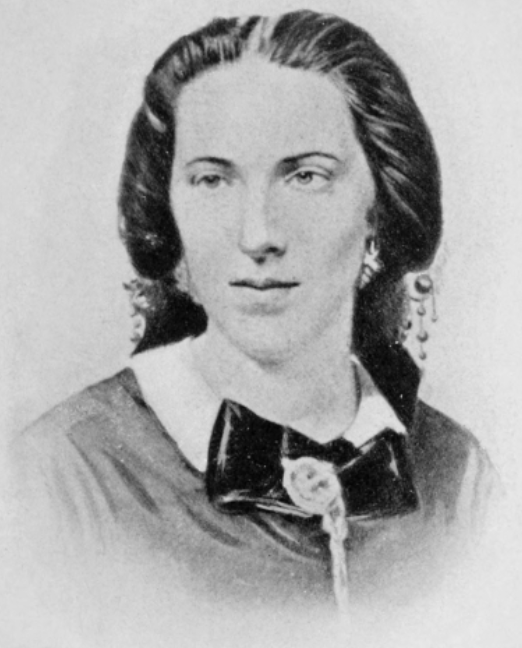

That brilliant writer, Gilbert Chesterton, in one of his paradoxical essays said that a fact, if looked at fiercely, may become an adventure. It is certain that the most important facts in the life of Belle Boyd, the Confederate spy, constitute some of the most thrilling adventures in the great conflict between the sections—the Civil War in the United States.

She was only a girl when the flag was fired on at Sumter and her father and all the members of her family immediately enlisted in the Confederate army. When the Union troops took possession of Martinsburg, Belle Boyd found herself unwillingly inside the Federal lines. She had no formal commission from any of the Southern officers, but circumstances and her ardent nature made her an intense partisan of what was to be “The Lost Cause.”

During the occupation of Martinsburg, she shot a Union soldier, who, she claimed, had insulted a Southern woman. From that moment until the close of the war she was actively engaged either as a spy, a scout or an emissary of the Confederacy. On more than one occasion she attracted the attention of Secretary of War Stanton, and although she served a term in a military prison, she seems to have been treated with unusual leniency. After the war she escaped to England, where she published her autobiography, bitterly assailing the victorious North.

It was in Martinsburg that Belle Boyd first began her work for the Confederacy. The Union officers sometimes left their swords and pistols about the houses which they occupied, and later were surprised and mystified at the strange disappearance of the weapons. They little thought that this mere slip of a girl was the culprit. Still later they were amazed to find that these same swords and pistols had found their way into the hands of the enemy and were being used against them.

But aside from this Belle Boyd made it her business to pick up all the information that was possible concerning the movements and the plans of the Union forces. Every scrap of news she obtained was promptly conveyed to General J. E. B. Stuart and other Confederate officers.

It was about the time of the battle of Bull Run that the Confederate general in command fixed upon Front Royal as a site for a military hospital. Belle Boyd was one of the nurses and many a fevered brow felt the touch of her cool hand and more than one stricken soldier afterwards testified to the loving care he received from this remarkable woman.

Later, Front Royal became the prize of the Union army, and Belle Boyd naturally fell under suspicion. Some remarks of her activities had already reached the front, and the officers kept her under close scrutiny. Fortunately, as she thought, she had been provided with a pass which would permit her to leave the place. Accordingly, the second day after the arrival of the Unionists she packed her grip and prepared to leave the town. As she came from the house she was halted by a Union officer named Captain Bannon.

“Is this Miss Belle Boyd?”

“Yes.”

“Well, I am the Assistant Provost Marshal, and I regret to say that orders have been issued for your detention. It is my duty to inform you that you cannot proceed until your case has been investigated.”

This did not suit the young woman at all. She opened her pocketbook and produced a bit of pasteboard.

“I have here a pass from General Shields. Surely that should be sufficient to permit me to leave the city.”

The young officer was perplexed. He did not care to repudiate a pass issued by General Shields, and at the same time did not wish to disobey the instructions which he had received from his immediate chief.

“I hardly know what to do,” he said. “However, I am going to Baltimore with a squad of men in the morning. I will take you with me and when we get there turn you over to General Dix.”

This program was carried out and the Confederate spy was given a free trip to the monumental city, which she did not want. She was compelled to remain in Baltimore for some time, being kept constantly under the closest supervision. Finally, however, General Dix gave her permission to return to her home. There was no direct evidence against her and it was considered a waste of time and energy to keep her under guard. She was escorted to the boundaries of her old home by two Union soldiers. It was twilight when she arrived at the Shenandoah River. The effects of the war were to be seen on every side. The bridges had been destroyed, and they only managed to cross the river by means of a temporary ferry boat that had been pressed into service.

When she reached her home she found that it had been appropriated as a headquarters by General Shields and the members of his staff. He treated her courteously and said that no harm would befall her if she was discreet and attended to her own business. She was told that a small house adjoining the family dwelling had been set aside for her use, and that the soldiers would be given orders not to molest her in any way.

But the young daughter of the Confederacy kept her eyes and ears open and the night before the departure of General Shields, who was to give battle to General Jackson, she learned that a council of war was to be held in the drawing-room of the Boyd home. Just over this apartment was a bedroom containing a large closet. On the night of the council she managed to make her way to this room and slipped into the closet. A hole had been bored through the floor, whether by design or otherwise she was unable to tell. However, she immediately determined to take advantage of what she considered a providential situation.

When the council assembled the girl got down on her hands and knees in the bottom of the closet and placed her ear near the hole in the floor. To her great satisfaction she found that she could distinctly hear all of the conversation. The conference between the Union officers lasted for hours, but she remained motionless and silent until it had been concluded. When the scraping movement of the chairs on the floor below was heard she knew that everything was over so came out of her place of concealment. She was tired and her limbs were so stiff from remaining in that cramped position so long that it was all she could do to move. But she was full of grit and determination and as soon as the coast was clear she hurried across the courtyard and made the best of her way to her own room in the little house and wrote down in cipher—a cipher of her own—everything of importance that she had overheard.

After that it was but a matter of a few minutes to decide on her course of action. She knew that it would be extremely dangerous to call a servant or to do anything that might arouse the officers, who had by this time gone to bed, so she went to the stables and saddled a horse herself, and galloped away in the direction of the mountains. The moon was shining when she started on this wild ride. She had in her possession passes which she had obtained from time to time for Confederate soldiers who were returning south. Without them it would have been impossible for her to have accomplished her purpose. Before she had gone a half mile she was halted by a Federal sentry. He grabbed the bridle of her horse and cried out:

“Where are you going?”

“I am going to visit a sick friend,” was the ready response.

“You can’t do it,” he cried. “You ought to know that you can’t leave this place without a pass.”

“But I have one,” she said, with an engaging smile, and drew out the piece of pasteboard.

The guard looked at it dubiously, but it was in proper form and contained the necessary signature and he grudgingly permitted her to continue on her journey.

Twice again she was halted by sentinels and each time she told the same story and underwent the same experience. Once clear of the chain of sentries she whipped her horse and hurried ahead for a distance of fifteen miles. At that time the animal was in a perfect lather and when she pulled up in front of the frame house which was the dwelling place of her friends the horse was panting and trembling from the unusual exertion. She leaped from the animal’s back and going to the door rapped on it with the butt end of her riding whip. There was no reply, so she hammered harder than ever. Presently a window in the second story was cautiously opened and a head poked out and a voice called:

“Who’s there?”

“Belle Boyd, and I have important intelligence to give to Colonel Ashby.”

“My dear Belle!” shrieked the voice from the window. “Where in the world did you come from and how did you get here?”

“Oh, I forced the sentries,” was the reply, in a matter of fact voice.

Within sixty seconds the girl was in the house and receiving refreshments and telling her strange story to her wondering friend. The horse in the meantime was taken to the stable by a negro and carefully groomed and fed. Only after these important details had been attended to was the girl permitted to tell her story.

“I must see Colonel Ashby,” she said in conclusion, “and if you can tell me where to find him I will go at once.”

She was informed that the Confederate officer and his party were in the woods about a half mile distant from the place in which they were sitting. Just as the girl was ready to go the front door was thrown open and Colonel Ashby stood before her. He looked at her as if she were a ghost and then finally burst forth in amazement:

“My God, Miss Belle, is that you? Where did you come from? Did you drop from the clouds?”

“No,” she said smilingly, “I didn’t. I came on horseback and I have some very important information.”

Whereupon she related the details of the council that had taken place in the Boyd home, and then told the story of her mad ride through the night. She concluded by handing him the cipher, which he said would be communicated to his superior officers at once.

After that she insisted on mounting her horse and returning home again. It was more than two hours’ ride, during which time she ran the blockade of the sleeping sentries with comparative success. Just at dawn when she was in sight of her home one of the sentries she was passing called out:

“Halt or I’ll shoot!”

But she did not halt. On the contrary she whipped her horse until it fairly leaped through the air. She felt that the man was leveling his gun in her direction. She lay flat on her horse’s back with her arms around his neck, and this was done in the very nick of time, for at that same moment a hot bullet came singing past her ears. That was the only serious interruption. In a few minutes she had reached the grounds surrounding the Boyd home. Fortunately no one was in sight. She hurried into the house and went to bed in her aunt’s room just at the break of dawn.

Two days later General Shields marched south with the idea of laying a trap to catch General Jackson. Once again the fearless girl determined to carry the information she possessed to her Confederate friends. Major Tyndale, at that time Provost Marshal, gave Belle Boyd and her cousin a pass to Winchester. Once there a gentleman of standing in the community called on her and handing her a package, said:

“Miss Belle, I am going to ask you to take these letters, and send them through the lines to the Confederate army. One of them is of supreme importance and I beseech you to try and get it safely to General Jackson.”

After the exercise of considerable ingenuity she managed to get a pass to Front Royal. To add to the romantic feature of the business a young Union officer, who admired the girl, offered to escort her to her destination. They went in a carriage, but before starting she made it a point to conceal the Jackson letter inside her dress. The other letters, which were of comparatively small importance, she handed to the Union officer with the remark that she would take them from him when they reached Front Royal. On the way, as she feared, they were stopped by a sentinel. The Union admirer of the Confederate spy explained that they had a pass which would permit them to proceed on their way, but the zealous sentinel insisted on searching them and was highly indignant when he discovered the compromising letters in the hands of the young man. He insisted upon confiscating them, but in the excitement forgot all about the girl, and she was permitted to go unmolested, carrying with her the precious letter intended for General Jackson.

Afterwards she laughingly expressed contrition for having involved an ardent admirer in such a serious plight, but excused herself on the ground that all was fair in war as well as in love. Fortunately, the young man, who was a perfectly loyal Northern soldier, was given the credit of having discovered the papers, which were valuable to his superior officers. Thus do we sometimes make a virtue of necessity.

After Belle Boyd had been in Front Royal for several days she learned that the Confederates were coming to that place, but she also discovered that General Banks was at Strasbourg with 4,000 men; that White was at Harper’s Ferry; Shields and Geary a short distance away, and Frémont below the valley. At a spot which was the vital point all of the separate divisions were expected to meet and coöperate in the destruction of General Jackson. She realized that the Confederates were in a most critical situation and that unless the officers in command were aware of the facts they might rush into a trap which meant possible annihilation.

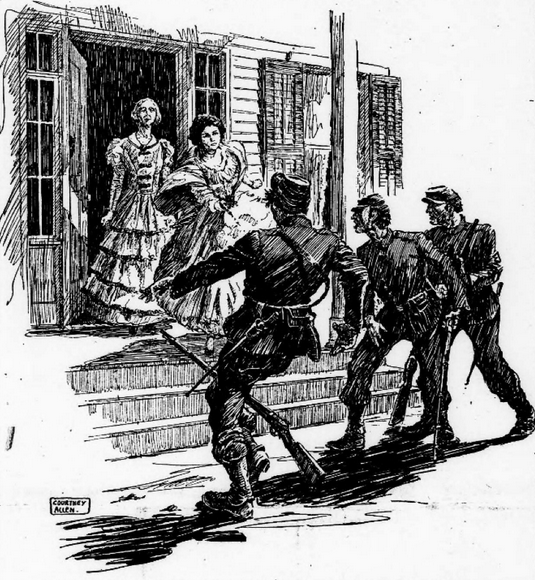

With characteristic promptness she decided on her plan of action. She rushed out to warn the approaching Confederates. On that occasion she wore a dark blue dress with a fancy white apron over it which made her a shining mark for bullets. The Federal pickets fired at her but missed and a shell burst near her at one time, but she threw herself flat on the ground and thus escaped what seemed to be sure death. Presently she came within sight of the approaching Confederates and waved her bonnet as a signal.

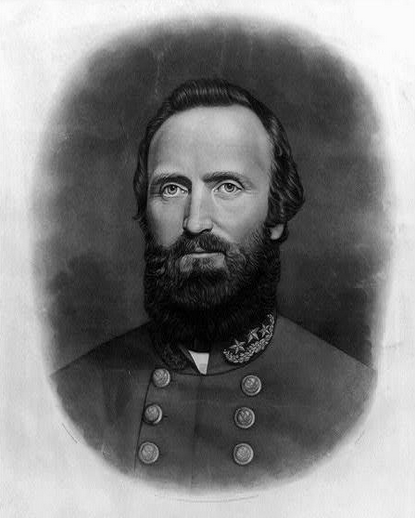

Major Harry Douglass, whom she knew, galloped up and received from her the information, which he immediately transmitted to General Jackson. The result of all this was a rout of the Union forces.

It was in this battle of Bull Run which followed soon afterwards that General Bee, as he rallied his men, shouted:

“There’s Jackson standing like a stonewall!”

From that time, as has been aptly said, the name he received in a baptism of fire displaced that which he had received in a baptism of water.

The number of Union men engaged in the battle of Bull Run was about 18,000, and the number of Confederates somewhat greater.

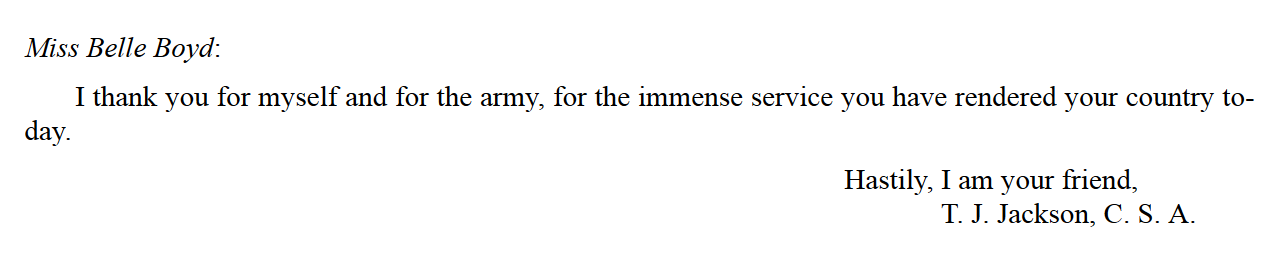

Soon after the engagement the young woman received the following letter, which she prized until the hour of her death.

Shortly before the close of the war Belle Boyd was captured and imprisoned. She escaped and made her way to England. In London she attracted the attention of George Augustus Sala, the famous writer. She had been married in the meantime and her husband, Lieutenant Hardage of the Confederate army, was among those taken prisoner by the Union forces.

While abroad she became financially embarrassed; indeed, at one time she was reduced to actual want. A stranger in a strange land, sick in mind and body, she was in a pitiable condition. Mr. Sala wrote a letter to the London Times explaining her sad state and roundly abusing the United States Government which had, he said, not only imprisoned her husband but was also “barbarous enough to place him in irons.”

British sympathies were very strongly with the South at that time, and as a result of this plea provision was made for the immediate wants of the famous spy. After the war she disappeared from the public gaze, and some years later died in comparative obscurity.

5