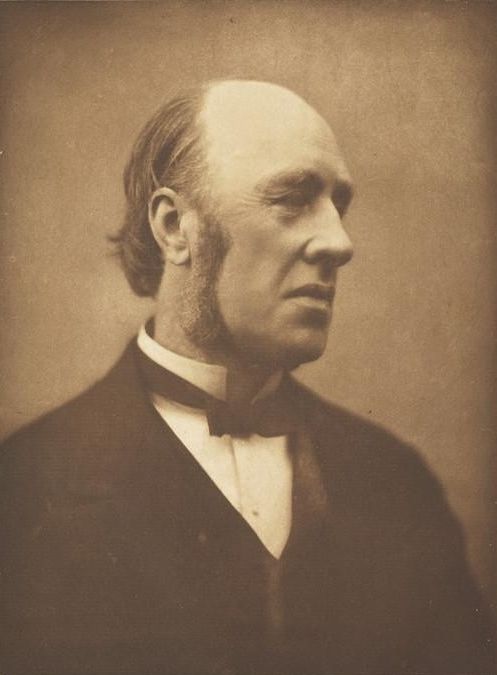

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Historical and Political Essays, by William Edward Hartpole Lecky (published 1908).

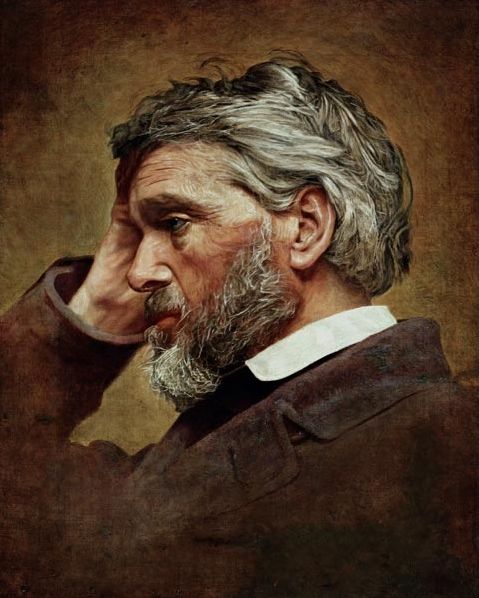

When Carlyle came to London in 1831, bringing with him the ‘Sartor Resartus,’ which is now perhaps the most famous of all his works, it is well known that he applied in turn to three of the principal publishers in London, and that each of them, after due deliberation, positively refused to print his manuscript. When at last, with great difficulty, he procured its admission into ‘Fraser’s Magazine,’ Carlyle was accustomed to say that he knew of two men who found anything to admire in it. One of them was the great American writer, Emerson, who afterwards superintended its publication in America. The other was a priest from Cork, who wrote to say that he wished to take in ‘Fraser’s Magazine’ as long as anything by this writer appeared in it. On the other hand, several persons told Fraser that they would stop taking in the magazine if any more of such nonsense appeared in it. The editor wrote to Carlyle that the work had been received with ‘unqualified disapprobation.’ Five years elapsed before it was reprinted as a separate book, and in order that it should be reprinted it was found necessary for a number of Carlyle’s private friends to club together and guarantee the publisher from loss by engaging to take three hundred copies. But when, a few years before his death, a cheap edition of Carlyle’s works was published, ‘Sartor Resartus’ had acquired such a popularity that thirty thousand copies were almost immediately sold, and since his death it has been reprinted in a sixpenny form; it has penetrated far and wide through all classes, and it is now, I suppose, one of the most popular and most influential of the books that were published in England in the second quarter of the century.

Such a contrast between the first reception and the later judgment of a book is very remarkable, and it applies more or less to all Carlyle’s earlier writings. It is a memorable fact in the literary history of the nineteenth century that one of the greatest and most industrious writers in England lived for many years in such poverty that he often thought of abandoning literature and emigrating to the colonies, and he would probably have done so if he had not found in public lecturing a means of supplying his frugal wants. The cause of this long-continued neglect is partly, no doubt, to be found in his style, for, like Browning, Carlyle wrote an English which was so contorted and sometimes so obscure that his readers had to be slowly educated into understanding, or at least enjoying, it. But there are other and deeper causes which I propose to devote the short time at my disposal to indicating.

It has been truly said that there are two great classes among writers. There are those who are echoes and there are those who are voices. There are some writers who represent faithfully and express strongly the dominant tendencies, opinions, habits, characteristics of their age, collecting as in a focus the half-formed thoughts that are prevailing around them, giving them an articulate voice, and by the force of their advocacy greatly strengthening them. There are others who either start new ways of thinking for which the public around them are still unprepared, or who throw themselves into opposition to the dominant tendencies of their times, pointing out the evils and dangers connected with them, and dwelling specially on neglected truths. It is not surprising that the first class are by far the most popular. The public is much like Narcissus in the fable, who fell in love with his own reflection in the water. All men like to find their own opinions expressed with a power and eloquence they cannot themselves attain, and most men dislike a writer who, in the first flush of a great enthusiasm, points out all that can be said on the other side. But when the first enthusiasm is over—when the prevailing tendency has fully triumphed and the evils and defects connected with it are disclosed—the words of this unpopular or neglected teacher will begin to gather weight. It will be found that although he may not have been wiser than those who advocated the other side, yet his words contained exactly that kind of truth which was most needed or most generally forgotten, and his reputation will steadily rise.

This appears to me to have been very much the position which Carlyle occupied towards the chief questions of his day, and it explains, I think, in a great degree the growth of his influence. It is remarkable, indeed, how many things there are in his writings which appeared paradoxes when he wrote, and which now seem almost truisms. Thus at a time when the political and intellectual ascendancy of France over the Continent was at its height, Carlyle was one of the few men who clearly recognised the essential greatness that lay hid in Germany, and especially in Prussia—a greatness which after the wars of 1866 and 1870 became very evident to the world. He was one of the first men in England to recognise the importance of German literature, and especially the supreme greatness of Goethe. His translation of ‘Wilhelm Meister’ was published in 1824, and his noble essay on Goethe in 1832; but at first it seemed to find scarcely any echo. The editor for whom he wrote it reported that all the opinions he could gather about this essay were ‘eminently unfavourable.’ De Quincey, who of all English critics was believed to know Germany best, and Jeffrey, who exercised the greatest influence on English literary opinion, combined to depreciate or ridicule Goethe. But there is now no educated man who disputes that Carlyle in this matter was essentially right, and that his critics were wholly wrong. And to turn to subjects more directly connected with England, Carlyle wrote at a time when the whole school of what was called advanced thought rested upon the theory that the province of Government ought to be made as small as possible, and that all the relations of classes should be reduced to simple, temporary contracts founded on mutual interest. According to this theory, it was the one duty of Government to keep order. For the rest it should stand aside, and not attempt to meddle in social or industrial questions. The most complete liberty of thought and action should be established, and everything should be left to unrestricted competition—to the free play of unprivileged, untrammeled, unguided social forces. This was the theory which was called orthodox political economy—the laisser-faire system—the philosophy of competition or supply and demand, and it was incessantly denounced by Carlyle as Mammon worship, as ‘devil take the hindmost,’ as ‘pure egoism’; ‘the shabbiest gospel that had been taught among men.’ He declared that in the long run no society could flourish, or even permanently cohere, if the only relation between man and man was a mere money tie. He maintained that what he called the condition of England question, or, in other words, the great mass of struggling, anarchical poverty that was growing up in the chief centres of population, was a question which imperiously demanded the most strenuous Government intervention—which was, in fact, far more important than any of the purely political questions. The whole system of factory legislation, the whole system of legislation about working men’s dwellings, which has taken place in this century, has been a realisation of the ideas of Carlyle. When Carlyle first wrote, it was the received opinion that the education of the people was a matter in which the Government should in no degree interfere, and that it ought to be left altogether to individuals, or Churches, or societies. In his work on Chartism, which was published as early as 1834, Carlyle argued that the ‘universal education of the people’ was an indispensable duty of the Government. It was not until about twenty years ago that this duty was fully recognised in England. In the same work he maintained that State-aided, State-organised, State-directed emigration must one day be undertaken on a large scale, as the only efficient agent in coping with the great masses of growing pauperism. In his ‘Past and Present,’ which was published in 1843, he threw out another idea which has proved very prolific, and which is probably destined to become still more so. It is that it may become both possible and needful for the master worker ‘to grant his workers permanent interest in his enterprise and theirs.’

It is evident how much less strange those ideas appear now than they did when they were first put out some fifty years ago. One of the most remarkable changes that has taken place during the lives of men who are still of middle age has been in the opinion of advanced thinkers about the function of Government. In the early days of Carlyle the whole set, or lie[1], of opinion in England was towards cutting in all directions the bands of Government control, diminishing as much as possible the sphere of Government functions or interference. It was a revolt against the old Tory system of paternal Government, against the system of Guilds, against the State regulations which once prevailed in all departments of industrial life. In the present generation it is not too much to say that the current has been absolutely reversed. The constantly increasing tendency, whenever any abuse of any kind is discovered, is to call upon Parliament to make a law to remedy it. Every year the network of regulation is strengthened; every year there is an increasing disposition to enlarge and multiply the functions, powers, and responsibilities of Government. I should not be dealing sincerely with you if I did not express my own opinion that this tendency carries with it dangers even more serious than those of the opposite exaggerations of a past century: dangers to character by sapping the spirit of self-reliance and independence; dangers to liberty by accustoming men to the constant interference of authority, and abridging in innumerable ways the freedom of action and choice. I wish I could persuade those who form their estimate of the province of Government from Carlyle’s ‘Past and Present’ and ‘Latter-day Pamphlets’ to study also the admirable little treatise of Herbert Spencer, called ‘The Man and the State,’ in which the opposite side is argued. What I have said, however, is sufficient to show how remarkably Carlyle, in some of the parts of his teaching that were once the most unpopular, anticipated tendencies which only became very apparent in practical politics when he was an old man or after his death.

The main and fundamental part of his teaching is the supreme sanctity of work; the duty imposed on every human being, be he rich or be he poor, to find a life-purpose and to follow it out strenuously and honestly. ‘All true work,’ he said, ‘is religion’; and the essence of every sound religion is, ‘Know thy work and do it.’ In his conception of life all true dignity and nobility grows out of the honest discharge of practical duty. He had always a strong sympathy with the feudal system which annexed indissolubly the idea of public function with the possession of property. The great landlord who is wisely governing large districts and using all his influence to diffuse order, comfort, education, and civilisation among his tenantry; the captain of industry who is faithfully and honestly organising the labour of thousands, and regarding his task as a moral duty; the rich man who, with all the means of enjoyment at his feet, devotes his energies ‘to make some nook of God’s creation a little fruitfuller, better, more worthy of God—to make some human hearts a little wiser, manfuller, happier, more blessed,’ always received his admiration and applause. No one, on the other hand, spoke with more contempt of a governing class which had ceased to govern; of titles which had lost their original meaning, and no longer implied or expressed duties performed; of wealth that was employed solely or mainly in selfish enjoyment or in idle show. It was Carlyle’s deep conviction that the best test of the moral worth of every nation, class, and individual, is to be found in their standard of work and in their dislike to a useless and idle life. As is well known, he had no sympathy with the prevailing political ideas. He believed that men were not only not equal, but were profoundly unequal; that it was the first interest of society that the wisest men should be selected as its leaders, and that the popular methods of finding the wisest were by no means those which were most likely to succeed. ‘No British man’ he complained, ‘can attain to be a statesman or chief of workers till he has first proved himself a chief of talkers.’ ‘The two greatest nations in the world, the English and American, are all going to wind and tongue.’ He believed much more than his contemporaries did that there was need and room in our modern English life for strong Government organisation, guidance, discipline, reverence, obedience, and control. ‘Wise command, wise obedience,’ he wrote in one of his ‘Latter-day Pamphlets,’ ‘the capability of these two is the best measure of culture and human virtue in every man.’

There is another class of workers to which he himself belonged—the men who are the teachers of mankind. He taught them by his example as well as by his precepts. Whatever else may be said about Carlyle, no one can question that he took his literary vocation most seriously. He was for a long time a very poor man, but he never sought wealth by advocating popular opinions, by pandering to common prejudices, or by veiling most unpalatable beliefs. In the vast mass of literature which he has bequeathed to us there is no scamped[2] work, and every competent judge has recognised the untiring and conscientious accuracy with which he verified and sifted the minutest fact. His standard of truthfulness was extremely high, and one of his great quarrels with his age was that it was an age of half-beliefs and insincere professions. He maintained the religious beliefs which had once been living realities had to often degenerated into mere formulas, untruly professed or mechanically repeated with the lips only, and without any genuine or heartfelt conviction. He often repeated a saying of Coleridge: ‘They do not believe—they only believe what they believe.’ He used to speak of men who ‘played false with their intellects’; or, in other words, turned away their minds from unwelcome truths and by allowing their wishes or interests to sway their judgments, persuaded or half-persuaded themselves to believe whatever they wished. A firm grasp of facts, he maintained, was the first characteristic of an honest mind; the main element in all honest, intellectual work. His own special talent was the gift of insight, the power of looking into the heart of things, piercing to essential facts, discerning the real characters of men, their true measure of genuine, solid worth. Creeds, professions, opinions, circumstances, all these are the externals or clothes of men. It is necessary to look behind them and beyond them if we would reach the genuine human heart. One of the reasons why he detested what he called stump oratory was because he believed it to be the great school of insincerity. Its end was not truth, but plausibility. It was the effort of interested[3] men to throw opinions into such forms as might most captivate uninstructed men; to keep back every unpopular side; to magnify everything in them that was seductive. He once said to me that two great curses seemed to him eating away the heart of worth of the English people. One was drink. The other was stump oratory, which accustomed men to say without shame what they did not in their hearts believe to be true, and accustomed their hearers to accept such a proceeding as perfectly natural. And the same strong passion for veracity he carried into his judgment of other forms of work. Rightly or wrongly, he believed that the standard of conscientious work had been lowered in England through the feverish competition of modern times, and under the system of what he called ‘cheap and nasty’; that English work had lost something of its old solidity and worth, and was now made rather to captivate than to wear. Carlyle saw in this much more than an industrial change. He maintained that the love and pride of thorough work had long been a pre-eminently English quality, that it was the very tap-root of the moral worth of the English character, and that anything that tended to weaken it was a grave moral evil.

It is worth while trying to understand what truth underlay those parts of his teaching which seem most repulsive. The worship of force, which is so apparent in many of his writings, is a striking example. He was often accused of teaching that might is right. He always answered that he had not done so—that what he taught was that right is might; that by the providential constitution of the Universe truth in the long run is sure to be stronger than falsehood; that good will prevail over evil, and that right and might, though they differ widely in short periods of time, would in long spaces prove to be identical. Nothing, he was accustomed to say, seemed weaker than the Christian religion when the disciples assembled in the upper room; yet it was in truth the strongest thing in the world, and it accordingly prevailed. It was one of his favorite sayings ‘that the soul of the Universe is just,’ and he believed therefore that the ultimate fate of nations, whether it be good or bad, was very much what they deserved. It is curious to observe the analogy between this teaching and the doctrine of the survival of the fittest, which a very different teacher—Charles Darwin—has made so conspicuous.

He scandalised—and I think with a good deal of reason—most of his contemporaries by the ridicule which he threw upon the career of Howard, and upon the great movement for prison reform which was so actively pursued in his time. Much of what he wrote on this subject is, to me at least, very repulsive; but you will generally find in the most extravagant utterances of Carlyle that there is some true meaning at bottom. He maintained that the passion for reforming and improving prisons and prison-life had been carried in England to such a point that the lot of a convicted criminal was often much better that of an honest and struggling artisan. He believed that a just and wise distribution of compassion is a most important element of national well-being, and that the English people are very apt to be indifferent to great masses of unobtrusive, struggling, honourable, unsensational poverty at their very doors, while they fall into paroxysms of emotion about the actors in some sensational crime, about some seductive murderess, about the wrongs of some far-off and often half-savage race. ‘In one of these Lancashire weavers dying with hunger there is more thought and heart, a greater arithmetical amount of misery and desperation, than in whole gangs of Quashees.’[4] He maintained, too, that a strain of sentiment about criminals was very prevalent in his day, which tended seriously to obliterate or diminish the real difference between right and wrong. He hated with an intense hatred that whole system of philosophy which denied that there was a deep, essential, fundamental difference between right and wrong, and turned the whole matter into a mere calculation of interests. He was accustomed to say that one of the chief merits of Christianity was that it taught that right and wrong were as far apart as Heaven and Hell, and that no greater calamity can befall a nation than a weakening of the righteous hatred of evil.

The parts of Carlyle’s teaching on which I have dwelt to-day will be chiefly found in his ‘Past and Present,’ his ‘Heroes and Hero Worship,’ his ‘Latter-day Pamphlets,’ his ‘Chartism,’ and in the two admirable essays called ‘Signs of the Times’ and ‘Characteristics.’ In my own opinion, though Carlyle teaches much, his writings are most valuable as a moral force. Very few great writers have maintained more steadily that the moral element is the deepest and most important part of our being, deeper and stronger than all intellectual considerations. In his writings, amid much that has imperishable value, there is, I think, much that is exaggerated, much that is one-sided, much that is unwise. But no one can be imbued with his teaching without finding it a great moral tonic, and deriving from it a nobler, braver, and more unworldly conception of human life.

___________________________________

[1] Direction, trend [ed.]

[2] Perfunctory or inadequate [ed.]

[3] Having an interest or involvement; not impartial [ed.]

[4] Natives of the West Indies [ed.]

A very interesting article – but the following section : “There is another class of workers…” to ” …It was the effort of interested” is mistakenly printed twice before the full paragraph is eventually given!

Corrected. Thanks for noting this.