Editor’s note: The following comprises the eighth chapter of Defenders of the Faith: The Christian Apologists of the Second and Third Centuries, by the Rev. Frederick Watson. M.A. (published 1879).

CHAPTER VIII

The Latin Apologists

We pass on to consider the Latin Apologists, who lived in the 3rd century A.D. We do not find them, as we might have expected, in the Church of Rome. In these early times she was distinguished rather for her zeal for the purity of the faith than for her learning. The African Church, now so utterly fallen to decay, gave to the Christians the earliest defenders who wrote in the Latin tongue.

TERTULLIAN. 150-220 A.D.

The first in time, and in other respects the most important of all the Latin Apologists, is Tertullian. Of his life we know little, but his works are most numerous and valuable, and leave untouched few points relating to Christian faith and practice. Amongst them are contained four treatises of an Apologetic nature. Two only need be considered by us, his “Apologetic Book,” and his “Testimony of the Soul.”

The Apology. — No early defence of the Christians can be compared in force and completeness with the ” Apologetic Book ” of Tertullian. We miss, indeed, that moderation, and elegance, and wide sympathy, which are found so markedly in the “Embassy” of Athenagoras. One cannot help feeling that Tertullian’s logic was too keen for his purpose. He seems to wish to prove his case, rather than to win his cause. It was dangerous and impolitic to press home arguments, when the enemy had material power on his side. Retort was out of place in an Apology. It only embittered the controversy, and conciliation was required. Such considerations were, however, quite beneath Tertullian’s notice. He seems to have been of a stern and harsh character. His own religion, and his judgment on that of others, were hard and unsympathizing. Hence we find him attacking the heathen with relentless vigour. His is not the tone of a suppliant pleading for toleration. He demands justice. Arraigned as a criminal at the bar, he accuses and condemns his judges.

His Apology was addressed to the governors and proconsulars of Africa, and was written almost exactly at the commencement of the third century. Like most of the Apologies, it is an appeal to the authorities that the Christians should not be condemned unheard. Tertullian opens his case by objecting to the mode of procedure at the trials. The forms of law were not observed. The accused were not allowed to defend themselves against the popular accusations. Their treatment was wholly different from that adopted at the trials of other criminals. When accused of the crime of Christianity, confession of guilt was followed by torture to force them to a denial of guilt. On the other hand, a denial of their guilt was at once accepted, and they were let go free. Inasmuch as, in the courts, all turned on the answer to the question, “Are you a Christian?” it came to pass that the title Christian summed up in one word all the reproaches and accusations which the hatred of the times had invented. What is there in this name to excite your hatred? whether it be Christian, which speaks of anointing and Christ our founder, or Chrestian, as you wrongly call it, which tells of sweetness and benignity.

Proceeding from the trial to the accusation (c. 4), Tertullian is the first of the Apologists who goes fairly into the charge, that the Christians formed a body unrecognized by law.

When the Christians had been able to prove their innocence of the crimes charged against them, their accusers fell back on the authority of the laws, and said, “It is not lawful for you to exist.” Tertullian argues that justice is the foundation of law. A thing should be unlawful, not because men wish it so to be, but because it ought so to be. This particular law has not dropped down from heaven; if it is a bad one, it can be repealed. Laws have been changed, are being changed every day, and many still require to be changed; then why not this, if reason be shown? He remarks that the laws against the Christians were only enforced by unjust and wicked emperors, — emperors like Nero, the first to assail them, and like Domitian, a man of the same type in cruelty; emperors like Trajan, Antoninus Pius, or Marcus Aurelius, had never persecuted them.[1] “What sort of laws,” he asks, “are these which the impious only use against us? Moreover, who are you, that you should set yourselves up as protectors of the laws and institutions of your fathers? Where is the ancient simplicity of life, and purity of morals? It is utterly gone. What has become of your ancient religion? You have introduced new gods. In your dress, your food, your style of life, in your opinions, and even in your speech, you have renounced your ancestors.

Proceeding to the charges of immorality, Tertullian argues that they rest, notwithstanding watches and surprises, on rumour only. “Everybody knows what sort of a thing rumour is; it is essentially lying. Even its truths are mixed with falsehood; it is the very designation of uncertainty. It has no place when proof is given and the truth is known. Does any but a fool put his trust in it? Yet it is the only witness you can bring against us (c. 8). Moreover, these charges are intrinsically improbable. Human nature is incapable of such baseness. Christians are men as well as you.” Then, curiously but characteristically enough, Tertullian turns round (c. 9), and retorts the same charges against the heathen; in so doing, he overthrows, of course, this last argument.

The theological charge next receives his attention (c. 10). “You do not,” said the heathen, “worship the gods, and you do not offer sacrifice to the Emperor.” His answer is, “No, we do not; for the gods you worship are no gods at all.” To prove his point he examines the statements made concerning them in heathen books; he shows that they are not gods by nature, but originally men; that they were not made gods, either because the great God needed their aid, or wished to reward their merit (c. 11). The God who created and ordered the world in the beginning, needed no help from men for the governing of it. The merits of the heathen deities were not of a kind to have raised them to heaven, but rather to have sunk them into the lowest depths of hell. As for the images of the gods, in what do they differ from common vessels and utensils?

He draws an amusing parallel between the making of images and the persecuting of Christians. The heathen make gods in the same way that they kill Christians. “In their fashioning you fix them to frames, and in our execution you fix us to crosses and stakes; you tear our sides with claws, you use axes, and planes, and rasps on every member of their body. We are headless when you have done your worst upon us, they are headless before you have used your lead, and glue, and nails. You drive us to wild beasts, and lions and tigers are their constant attendants. We are burnt in the fire, and so is the metal of which they are composed. We are condemned to the mines, and from thence their original lump came. We are banished to islands, — in islands it is common for the gods to be born or to die. Spite of all this, ‘They are gods to us,’ you say (c. 12). Indeed! How is it, then, that you are convicted of impious and sacrilegious conduct to them? With you, deity depends upon a decision of the Senate. With you, gods are pledged, sold, broken up, changed into cooking-pots and firepans. With you, deity is made a gain of and farmed out to the highest bidder. The more sacred a god is, the larger is the tax he pays. Majesty is made a source of gain. Religion goes about the taverns begging. You enrol amongst your ancient gods your prostitutes, and sorcerers, and infamous court pages (c. 14). You offer as sacrifices diseased and dying animals (c. 15). You insult your objects of worship, in your books and theatres by your scoffs, in their temples and at their very altars by your crimes” (c. 16).

After denying the truth of certain absurd stories as to the object of the Christian worship, Tertullian describes what that object really is (c. 17). It is the one God, the Creator of all things, Invisible, Incomprehensible, the true God because immensely great. To Him His great and manifold works, and the simple soul of man bear witness (c. 18). Not these alone, His written Word also, — the writings of just men on whom He poured His Spirit; ancient writings, as the facts of history show (c. 1 9); true writings, as the fulfilment of prophecy proves (c. 20).

Up to this point, no Christian, as distinguished from Jewish, elements, have been introduced; but now Tertullian states the fundamental distinction between Judaism and Christianity (c. 21). The Jews consider Christ to be a mere man; the Christians believe Him to be God. He describes the nature of Christ’s divinity. He is the Word of God, by whom all things were made. As the rays proceed forth from the sun, and there is no division, so the Son of God came forth from His Father, and yet the two are one. The Word was made flesh and dwelt amongst us, and proved His divinity by His wonderful works in His life, and His death, and His resurrection. Of these things Pilate was a witness, who sent an account of them to Tiberius. Is there, then, anything in the origin and Founder of our Name that should cause you to persecute it so cruelly? Your duty is to search and see whether the divinity of Christ is true. If the acceptance of its truth transforms a man and makes him truly good, then you are bound (as we have felt ourselves already) to renounce the worship of other gods.

Tertullian now describes what the heathen worship really is. It is worship of demons. It is they who give to the heathen religion its power over men. They are the cause of all the mischief on the face of the world. Their great business is the ruin of mankind. Still, all unwillingly, they are most effective witnesses for Christ. When those possessed by them are brought to us, and we adjure them in the name of Christ, they confess what they are, even the gods you worship, and they bear testimony to the truth of Christian doctrine. Fearing Christ in God, and God in Christ, they become subject to the servants of God and Christ (c. 23). So at one touch and breathing, overwhelmed by the thought and realization of the judgment fires, they leave at our command the bodies they have entered, unwilling and distressed, and put to open shame (c. 24). The whole confession of these beings, in which they declare they are no gods, and that there is no God but one, — the God whom we adore, is quite sufficient to clear us from the crime of treason against the Roman religion. If these gods have no existence, there is no religion in the case. Even if they have an existence, is it not generally held that there is One above them? Can we give His glory to another? Under any circumstances is unwilling homage of any value? All other nations, provinces, and even cities, have their own gods, why should we only be prevented from having a religion of our own?

The objection is now started, If the Christian theory is true, the heathen gods are no gods at all, and yet history shows that the Romans have been prosperous because they have been pious. Tertullian is treading on delicate ground now, and he is not the man to tread delicately (c. 25, 26). He proves, and proves conclusively, that history does not bear out this theory. The Romans were great before they were religious; they triumphed over gods, and not till then worshipped them. But he is not satisfied with this. He finds instances where the gods did not exercise their power in the defence of their worshippers, and he brings these forward as proofs of want of power. Non-exercise of Divine power, according to Tertullian, proves its non-existence. Every martyrdom showed the fallacy of this argument.

The last charge Tertullian meets is that of treason against the Emperor (c. 28). It was based simply on the fact that the Christians refused to pay him divine worship (c. 28-36). As Tertullian explains, the Christian religion forbids its followers to invoke a mere man — even the ruler of the world; but it requires them to invoke God for his safety, and to pay him the respect due to his position and to the minister of God (c. 32). They have special reasons for their prayers, for with the fall of the Roman empire will come the violent commotions which are impending over the whole world. As usual, Tertullian is not satisfied with showing that the Christians are loyal, but he proceeds to show that they alone are loyal (c. 35-38), he points to the prevalence of treason. In spite of the provocation the Christians have received, their names are not to be found in the lists of conspirators; their numbers make them formidable, but their principles make them harmless (c. 37).

Tertullian next explains (c. 38, 39) the nature of the Christian Society, with the intention of showing that it contains none of the characteristics of a faction, nothing to make it formidable to the State, and, therefore, nothing to prevent its toleration. He asserts (c. 40) that the Christians, so far from being the cause of public calamity, have been in reality the very salt of the earth. He meets and denies the charge of unprofitableness in the concerns of life (c. 42). He boasts of the superior morality of the Christians (c. 43, 44), and ascribes it to their rule of life, which is not human, but divine (c. 45).

And now we notice one of the characteristics of the Latin Apologists (c. 46): he is most anxious to maintain the independent claims of Christianity. Unbelief, convinced of the worth of Christianity, suggested that it was, notwithstanding, not really divine, but only a kind of philosophy. Innocence, justice, patience, sobriety, and chastity, were just the very things which the philosophers counselled and professed. “Is this so?” says Tertullian, “then why do you not treat us like the philosophers? No one compels a philosopher to sacrifice or take an oath. Nay, they openly overthrow your gods, and you applaud them for it. But are we, indeed, like the philosophers? Far from it. The name of philosophers drives out no wicked spirits; philosophers merely affect to hold the truth, and all the while they corrupt it. We Christians ardently and intensely long for it, and maintain it in its integrity. We are like philosophers neither in our knowledge nor in our ways. The philosophers do not know God; but He has been revealed to us. The philosophers do not practise the virtues they recommend: we must and do. No doubt the teachings of the philosophers and the Christians are, in some respects, similar (c. 47). The reason is, the poets and sophists have drunk from the fountain of the prophets. At least we are entitled to argue that our doctrines are not utterly foolish, if like to those of your wisest men (c. 49). The ideas, which in them are called sublime speculations and illustrious discoveries, cannot be called in us presumptuous speculations. If they are men of wisdom, we cannot be fools.”

Tertullian concludes by appealing against the heathen cruelty (c. 50). The Christians glory in their sufferings, but they do not suffer willingly. They desire to suffer as the soldier longs for war. In suffering they reap glory and spoil, and in death they win the victory. The cruelty of the heathen is of no avail; the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church; the deeds of the Christians find more disciples than the words of the philosophers. No one who sees the fortitude of the Christians, fails to inquire what is the cause of it; no one who has inquired, fails to embrace their doctrines ; no one who has embraced their doctrines, is unwilling to suffer for them, and thus obtain from God full forgiveness.

Tertullian’s Apology is remarkable for its arrangement. He had a definite plan, and he always kept to it. He shows great discretion in the choice of his authorities. Elsewhere, he constantly quotes the Scriptures ; here, very rarely. When he alludes to them, it is not to appeal to their authority but as containing information on Christian doctrine. Whatever its faults, the Apology of Tertullian holds the first place among the apologies of the age. It meets the accusations fully and completely, and so accomplishes its chief purpose. No one can fail to admire its earnest spirit. Although narrow and harsh in its judgments, it is the warm appeal of a warm heart.

The Testimony of the Soul. — We must not pass over, without notice, the argument against heathenism we find in Tertullian’s treatise ‘On the Testimony of the Soul.’ He alone, of all the Apologists, refuses to search heathen literature for testimonies in favour of Christianity. Such arguments, he conceived, were easily set aside; they required great research for their acquisition, and a retentive memory for their use. So, in their place, he calls in a new witness, a witness more simple and better known — The soul of man ; meaning thereby that part of man’s nature which makes him a rational being in the highest degree capable of thought and knowledge. He will not have, indeed, the soul trained, and fashioned in, and corrupted by, the wisdom of the world, but the soul simple, rude, unlearned, untaught, as far as might be, except by itself and its Author. Not yet Christian, he presses it for a testimony on behalf of Christians. He draws this testimony from certain expressions which it uses naturally and constantly. When expressing its hopes and wishes, it does not invoke the gods for help, but it says, “Which may God grant,” “If God so will.” It thus acknowledges that there is One who is God and Sovereign. Yet again, it says, “God is good,” and “God does good,” and thus it declares the nature of God; and, by contrast, it seems to imply that man is evil, and has departed from God. It says, “God sees all; I commend thee to God:” “May God repay”; “God shall judge betwixt us”; and thus it confesses God’s providence, His power, His justice, and a future retribution. It gives these testimonies whilst in the temples, and whilst engaged in the sacred rites. In the immediate presence of its gods, it appeals to the God who is elsewhere. And, besides, it gives a testimony to the immortality of the soul. When it speaks of the dead, it says, “Poor man.” Why is a dead man poor, if he has lost the burden of life, and is beyond the feeling of pain? It curses the dead who have wronged it, and it blesses the dead to whom it is indebted for favours. It thus shows that they are not, in its idea, beyond the reach of blessing and curse. It says of one lately dead, “He is gone.” He is expected to return, then. Nor can these testimonies be considered frivolous or feeble when it is recollected that the soul derives all its knowledge from Nature, and that Nature’s teachings are derived from God. Is it a wonderful thing that, fallen though it is, it cannot forget its Creator, His goodness and His law, and its own end? Is it wonderful that, being divine in its origin, its revelation agrees with those made by God to His people in the Jewish Scriptures?

There is an obvious answer to this argument which Tertullian mentions. The expressions he has alleged may be only an accommodation to existing prejudices; they may have had their origin and become common from arguments used in books. To meet this, he appeals to the nature of language. A word is but an embodiment of a thought: thoughts are the offspring of the soul; words existed long before books; before the cultivated poet or philosopher came the rude and simple man. We have then to search for the origin of such expressions in the nature of man, who found need for them as expressing some deep feeling within him, or some truth which had been revealed to him from the beginning. If, indeed, the soul has taken them from writings at all, it must have done so from the earlier and not later ones, and the Scriptures of God are much more ancient than any secular literature.

And so Tertullian calls upon the heathen to give credence to the witness of the soul. He asks them to consider how it is it uses Christian phrases, though it hates Christians. From the whole wide world its testimony comes. “There is not a soul of man that does not,” he says, “from the light that is in itself, proclaim the very things we are not permitted to speak above our breath. Most justly, then, every soul is a culprit as well as a witness. In the measure that it testifies for truth, the guilt of error lies on it. On the day of judgment it will stand before the courts of God without a word to say. Thou proclaimest God, O soul, but thou didst not seek to know Him. Evil spirits were detested by thee, and yet they were the objects of thy adoration; the punishments of hell were foreseen by thee, but no care was taken to avoid them; thou hadst a savour of Christianity, and withal wert the persecutor of Christians.”

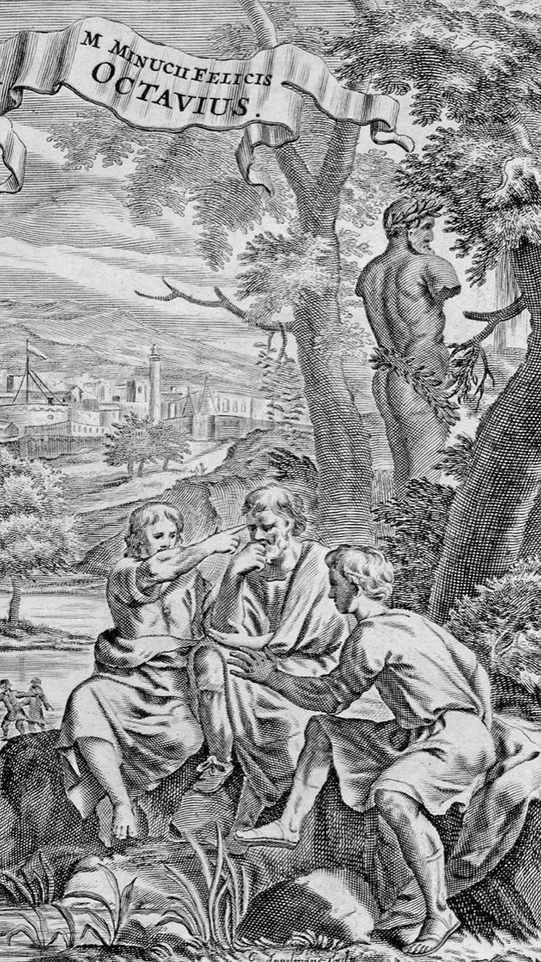

MINUCIUS FELIX. 2OO-25O A.D. CIRCA.

The Octavius of Minucius Felix is a lively and elegant Apology in the form of a dialogue between a Christian, Octavius (whence its name), and a heathen, Caecilius. It is remarkable for giving a clear and complete picture of the Christians and their religion as they appeared in the eyes of the heathen world. In the introduction Minucius describes Octavius, then dead, as his most intimate friend. “He had been,” he says, “my confidant in my love affairs, and my companion in my mistakes. When I emerged from the abyss of darkness into the light of wisdom and truth, he did not cast me off, but, — what is more glorious, — he outstripped me.” The scene (so to speak) of the dialogue is laid as follows: On one occasion Octavius had come to Rome during the vacation time to visit Minucius. Along with Caecilius, a constant companion of the latter, they had gone to Ostia to take the mineral baths. Early one morning they were all walking together along the banks of the Tiber close to its mouth, and enjoying the gently-breathing air and soft yielding sand. Caecilius perceived an image of the Egyptian god Serapis, and following the custom of the superstitious common people, he raised his hand to his mouth and kissed it. At once Octavius reproved Minucius for suffering his friend to remain in the darkness of idolatry. It was not the part of a good man so to do. The error of his friend was reflected upon himself. At the moment nothing more seems to have been said on the subject. They have now come to the sea-shore, and they walk along the beach. “There the gently rippling wave was smoothing the outside sands, as if it would level them for a promenade; and as the sea is always restless even when the winds are lulled, it came up on the shore, although not with waves crested and foaming, yet with waves crisped and curling. Just then we were excessively delighted at its vagaries, as on the very thresh old of the water we were wetting the soles of our feet, and now the wave broke over them, and then retiring sucked itself to itself.” As they walked along, Octavius beguiled the way with stories of navigation. On their return they came to a place where boats were lying on wooden slips, and they saw some boys eagerly gesticulating as they played at throwing shells into the sea. “This play is; to choose a shell from the shore, rubbed and made smooth by the tossing of the waves; to take hold of the shell in a horizontal position with the fingers; to whirl it along sloping and as low down as possible on the waves, that when thrown it may either skim the back of the wave, or may swim as it glides along with a smooth impulse, or may spring up as it cleaves the top of the waves, and rise as if lifted up with repeated springs. That boy claimed to be conqueror whose shell both went out furthest and leaped up most frequently.”

All this while Caecilius was silent and sulky, and Minucius asks, “What is the matter? Why are you not so lively as usual?” The answer is, that he is nettled at Octavius’ speech and indirect imputation of folly, and is anxious for an argument with him. He suggests that they seat themselves on the rocky barriers that are placed for the protection of the baths, and argue there. The suggestion is carried out, Minucius is placed in the middle as arbiter, and Caecilius begins.

After reminding Minucius that, though a Christian, he as judge must hold the balance even, he begins by remarking that there is no difficulty in making plain that all human affairs are doubtful, uncertain, and unsettled, and that all things are rather probable than true. Such being the case, all men must be indignant that certain persons, and these unskilled in learning, and strangers to literature, and without knowledge of the common arts, should dare to determine with certainty matters on which different religions differed, and on which philosophy still deliberated. When you examine Creation, you cannot find its origin. When you observe events in the world, you can find no order or discrimination, and no distinction between the good and the bad. Fortune unrestrained by laws seems to be ruling over us. Under these circumstances it is better to receive the teaching of our ancestors, and to assert no opinion about the gods. Each people has its national rites of worship, and adores its local gods. The Romans, adoring all divinities, have conquered all nations. Their wars have always been religious. When conquered at home, they still worshipped the gods who had not taken care of them; when conquerors abroad, they venerated the conquered deities. In all directions they seek for the gods of the strangers and make them their own. Experience has shown that this devotion is expedient. This attention to religion has given prosperity. Neglected auguries have brought with them disaster. The philosophers are not, therefore, to be listened to when they strive to undermine a religion so ancient, so useful, and so wholesome. Much less is it to be tolerated that men of a reprobate, and unlawful, and desperate faction, gathered from the lowest dregs of the people, leagued together by nightly meetings and inhuman rites, a people skulking and shunning the light, should rage against the gods. This wicked confederacy grows daily, and assuredly ought to be rooted out and execrated. Its worship is secret, by report abominable, certainly suspicious. Unless it was vile, why do its followers conceal it so carefully ? Why have they no altars, no temples or acknowledged images.

Proceeding to discuss Christian doctrines, The Providence of God extending over each and all, The destruction by fire of the eternal order constituted by the Divine laws of nature, The resurrection of the body after it has been resolved into dust, are marked out by Caecilius as specially foolish. He argues that the present condition of the Christians is a sufficient proof of the vanity of their hopes. The greater part of them are in want and cold, and their God suffers it. Why? Because he is either unwilling or unable to assist his people. Those who dream of immortality are shaken by danger, consumed by fever, and torn by pain. Yes, and they have special troubles. For them were threats, punishments, fines, and crosses not for adoration, but for torture. Who was that God who was able to bring them to life again, when He was unable to help them whilst in life? Of all men they were the most miserable in life, and there was nothing beyond. Cease, Caecilius exhorts them in conclusion, to pry into the regions of the sky. All matters relating to the gods are uncertain, and had far better be left as we find them. And now Caecilius has talked himself out of his temper, and exults in the prospect of a decided victory; but Minucius asks him to restrain his self-approval till he has heard the other side.

Octavius, in his reply, first remarks on the doubtful position of his opponent, at one time believing the gods, at another quite doubtful on the subject. He answers the objection brought against the Christians as illiterate, poor, unskilled people, by remarking that wisdom is not obtained by wealth, but implanted by nature. It is quite true that man ought to know himself, and should study the works of nature. But when you lift up your eyes to heaven, and look into the things below and around, what can possibly be more evident than that there is some God of most excellent intelligence by whom all nature is inspired, moved, nourished, and governed? The movements of the stars in the heavens, and the order of the seasons upon earth, the ebbs and flows of the tides, and the perpetual flowing of the fountains and rivers, the varied faculties of the animals, and, above all, men, with their body of upright stature, and many members all beautiful and necessary, all having the same general form, and yet so unlike in special features, — all these need a Supreme Artificer and perfect Intelligence to create, to fashion, and to arrange them.

Proceeding to show that God’s care is manifestly exerted, not only over the whole universe, but over its several parts, he makes a remark specially interesting to us: “Britain,” he says, “is deficient in sunshine, but is refreshed by the warmth of the sea that flows around it.” The house of the world, he argues, being thus beautiful and well-ordered, the Lord of the house must be far greater and more glorious. The analogy of the history of the world shows that that Lord is one; the authority of the Divine empire cannot be sundered. Such is God’s greatness that He is incomprehensible, and so a name cannot be given Him. Nor is this necessary. Being unique, He needs not to be distinguished from others by a name. All these truths are confirmed by the discourse of the common people, and the testimonies of poets and the wisest philosophers. Why, then, should men be carried away by the errors of their credulous ancestors?

Going into detail, Octavius shows the human origin of the gods, the ridiculous and corrupting character of their history and their rites of worship. He dissociates Roman prosperity from Roman religion. He shows that the oracles were unreliable, and traces their power to the demons. He claims that the demons are subject to the powers of the Christians. He rebuts the accusations of immorality and unworthy and infamous objects of worship; and he contrasts the lives of Christians with those of heathens.

Not by a small bodily mark, as Caecilius had supposed, are Christians distinguished, but very plainly by the sign of innocency and modesty. They love one another, because they do not know how to hate. They call one another brethren, because they are born of one God and Parent, because they are companions in faith, and co-heirs in hope.

Nor again is it for purposes of concealment that they have no temples, and altars, and images. Image of God there can be none, except man. Temple of God cannot be built, since the world itself cannot contain Him. The sacrifices to be offered to God are not sheep and cattle — His own gift to men; but a good soul, and a pure mind, and a sincere judgment. Certainly the God whom Christians worship, they can neither show nor see. We cannot even look upon or into His works, how then can we look upon Himself? And yet He is not far away and ignorant of men’s doings. All things are full of Him. We live under His eyes, and even in His bosom.

After showing the possibility of a dissolution of all things, and adducing the argument from analogy which nature gives to the doctrine of the resurrection, he points out that God permits suffering as a trial and discipline. God’s soldier is neither forsaken in suffering, nor brought to an end by death. The Christian may seem to be miserable, but is not really so. Those only are truly wretched who know not God. Apart from the knowledge of God, what solid happiness can there be, since death must come? Like a dream, happiness slips away before it is grasped. The Christians use this world as not abusing it, and have their innocent enjoyments here; but they live in contemplation of the future, and are animated by the hope of future happiness.

When Octavius ceases to speak there is silence for a time, and then Caecilius breaks forth: “I do not wait for the decision. We are both conquerors; Octavius has conquered me, and I have conquered error. I yield to God. I have many questions yet to ask, not in a spirit of doubt but of inquiry.”

After a few words from Minucius, all separate, glad and cheerful. Caecilius, to rejoice that he had believed ; Octavius, to rejoice that he had conquered; and Minucius, the friend of both, to rejoice for both reasons alike.

CYPRIAN. 200-258 A.D.

Cyprian’s life was momentous in its issues, but his Apologetic treatises are short, and of no great importance, and are, in part, derived from the writings of former Apologists. His address to Demetrian, proconsul of Africa, contains a remarkable description of the sufferings the Christians had to endure: “You deprive,” he says, “the innocent, the just, the dear to God, of their home; you spoil them of their estate, you load them with chains, you shut them up in prison, you punish them with the sword, with the wild beasts, with the flames. Nor, indeed, are you content that we should have a brief endurance of suffering, and a simple and swift exhaustion of pains. You set on foot tedious tortures, by tearing our bodies; you multiply numerous punishments, by lacerating our vitals; nor can your brutality and fierceness be content with ordinary tortures. Your ingenious cruelty devises new sufferings. “Why,” he asks, “do you turn your attention to the weakness of our body? Why do you strive with the feebleness of this earthly flesh? Contend rather with the strength of the mind; break down the power of the soul; destroy our faith; conquer, if you can, by discussion; overcome by reason; or, if your gods have any deity and power, let them themselves rise to their own vindication, let them defend themselves by their own majesty.” He goes on to show that the heathen gods are all unable to protect themselves. They are the demons whom the Christians cast out. “Oh, would you but hear and see them when they are adjured by us, and are tortured with spiritual scourges, and are ejected from the possessed bodies with torture of words, when, howling and groaning at the voice of man and the power of God, feeling the stripes and blows, they confess the judgment to come! Come and acknowledge that what we say is true; and since you say that you thus worship gods, believe even those whom you worship; or, if you will even believe yourself, he (i.e. the demon) who has now possessed your breast, who has now darkened your mind with the night of ignorance, shall speak concerning yourself in your hearing; you will see that we are entreated by those whom you entreat, that we are feared by those whom you fear, and whom you adore; you will see that under our hands they stand bound and tremble as captives, whom you look up to and venerate as lords; assuredly, even thus you might be confounded in those errors of yours, when you see and hear gods, at once, upon our interrogation, betraying what they are, and even in your presence unable to conceal these deceits and trickeries of theirs.”

The claim which Cyprian here makes is a very remarkable one; and he is not alone in making it. Every Apologist, with one exception (Clement of Alexandria), asserts that the power of casting out devils was a power continuing in, and being constantly exercised by, the Christian Church. Tertullian is quite ready to rest the Christian cause on the result of the encounter of any Christian with any demoniac.

ARNOBIUS. 300 A.D. CIRCA.

Arnobius’s Apology is of great value. His rhetorical power was great. He wrote from the standpoint of an unbeliever, for he was not yet admitted into the Christian Church, and was evidently still ignorant of many of her doctrines. A professor of rhetoric at Sicca, in Africa, he had been active in his attacks on Christianity, and devoted in his worship of images. When he wished to become a Christian (led by visions, Jerome tells us), his sincerity was at first suspected, and he composed his Apology as a pledge of his good faith. Amongst all the Apologists he is able most clearly to distinguish the Christian and the heathen miracles. His exposure of heathenism contains passages of scathing, though somewhat too redundant, eloquence. Many of these have been already quoted in a compressed form.

Inasmuch as Christianity was well known when Arnobius wrote, he naturally touches on matters which had not been noticed by former Apologists. The writings of the New Testament were in heathen hands, and they were objected to as containing barbarisms and solecisms. Arnobius asks how the truth of the substance is affected by the roughness of the form. The Christians discuss matters far removed from mere display; and they consider how they may benefit their hearers, not how they may tickle their ears.

He discusses at great length the nature of the soul. He denies that it is immortal, or that it comes direct from God. If it were born of God, men’s lives would be pure, and their beliefs one and the same. He thinks that naturally a man does not differ in kind from the animals. He suggests an experiment to prove his point. He supposes an infant brought up in a place where no sound or cry, no beast or bird, no storm or man, ever comes. He is to be tended by a dumb nurse, and to be fed on an invariable vegetable diet. He is to drink no wine, but only water from the spring. Thus he is to pass his life for twenty or thirty years, and then he is to be brought into the assemblies of men and questioned who and what he is. Will he not stand speechless, with less wit and sense than any beast, ignorant of the names and natures of the things offered to him? Arnobius thinks that you have here a man in his natural condition, and that his utter ignorance shows that his soul cannot have a divine origin. Of course, the fallacy of his argument lies here, that faculties, if uneducated and undeveloped, are wholly lost. Arnobius took care to preserve the bodily life of his infant with food, he left the soul unprovided with food, and it necessarily perished.

In his seventh book he has an elaborate argument against material sacrifices. He wants to know for what reason they are offered. Are the gods of heaven nourished by them? Surely not, since they are immortal. Moreover, the substance of the sacrifice is not consumed by them, but by fire. What pleasure can the gods above take in the slaughter of harmless creatures? Even we, half savage men, take some pity when we see the victims bleeding. They are offered, men say, that the gods may lay aside their anger. But can passion be felt by the Deity? If it can, why should the killing of a pig, or the consuming of a pullet, or the blood of a goose, or a goat, or a peacock, bring them relief? Are the gods like little boys, who give up their fits of passion when gifts of sparrows, or dolls, or ponies, are made to them? Then again, why should the burden of men’s sins be cast on the innocent animals? He pictures an ox addressing Jupiter, and saying, that he had never done him wrong, or celebrated his games irreverently, or polluted his sacred groves. Man was the cause of all wickedness, why then should he (an ox) be slain to soothe the divine anger? Again, Arnobius objects, does not experience show that the sacrifices are of no avail for procuring benefits? Is it not dishonouring to the gods to suppose that their gifts are an object of sale, to be purchased by rich scoundrels, beyond the reach of the pious if poor? The gods, though not benefited, are honoured by the sacrifices, it is said. What! honoured by that foul smell which is emitted by burning hides, by bones, by bristles, by the fleeces of lambs, and the feathers of fowls! What kind of honour is it to invite a god to a banquet of blood, which he shares with dogs? What kind of honour is it to set on fire piles of wood, to hide the heavens with smoke, to darken with gloomy blackness the images of the gods? If dogs and asses, and swallows, and pigs were to offer sacrifices to you, how would you like it? Supposing the swallows consecrated flies to you, and the asses put hay upon your altars and poured out libations of chaff; supposing that the dogs placed bones on your altars, and the pigs poured out a horrid mess from their troughs, would you not be inflamed with rage? And then your sacrificial laws by which you offer different animals to different gods, how destitute of reason are they? Why do you offer a bull’s blood to Jupiter, and a goat to Bacchus, and a barren heifer to Proserpine? In a similar manner he exposes the folly of offering wine to the gods, as if they could be thirsty, and he shows how utterly impossible it is that they can take delight in the shameless games which are celebrated in their honour. He traces all these vicious opinions to this cause: — Men were unable to know what God is, they were unable to discern Him by the power of reason, and so they fashioned gods for themselves and like themselves.

LACTANTIUS. 250-325 A.D.

Lactantius’s ‘Divine Institutions’ was written when persecution had ceased. In the latter part of his work he goes quite beyond the Apologetic limits. His object was a very ambitious one. It was so to plead the Christian cause, as not only to overthrow former writers against it with all their writings, but also to cut off from future writers the whole power of writing and of replying. With one blow he hopes to overthrow all accusers of righteousness. He only asks for attention (v. 4), and then he will assuredly effect that man must either embrace Christian doctrine, or at least cease to deride it. He compares his work with that of other Apologists. Tertullian sought only to answer accusers, he seeks to instruct. Cyprian did not handle his subject as he ought, for he endeavoured to refute his adversaries by testimonies from Scripture which they did not admit, instead of by arguments and reason (v. 4). He intends to use the testimonies of philosophers and historians. There have been wanting amongst us, he says (v. 1), suitable and skilful teachers, who might vigorously and sharply refute public errors, and who might defend the whole cause of truth with elegance and copiousness. Tertullian had little readiness of speech, was not sufficiently polished, and was very obscure. He undertakes to plead the cause of truth with distinctness and elegance of speech, in order that it may flow with greater power into the minds of men, being both provided with its own force, and adorned with brilliancy of speech (i. 1).

If we had no other evidence than this criticism of former Apologists, and this self-complacent application of his own powers, we should, I think, be justified in assuming that the Apologetic period had nearly come to an end, and that Christians were no longer struggling for existence. Lactantius falls into some of the errors which he points out in others. If he is more eloquent, he is less forcible than some of those who had gone before. The most interesting part of his work is his refutation of Philosophy. He has a clear idea of the nature and causes of its failure, and he does not refuse to give it credit for that which it had been able to achieve. His work is not a defence of Christians from accusations; he defends them, indeed, from the charge of foolishness, but does not refer to any charges of immorality or impiety. Christianity was much better known than in the first Apologists’ time. The ground was cleared for a work like the ‘Divine Institutions,’ which should discuss in greater detail the nature and evidence of a religion which had, single-handed, fought a battle against the Roman State, and won a complete victory.

CONCLUSION.

And now our task is complete. We cannot sum up our results better than in the noble words of an unknown Apologist.

“The Christians are distinguished from other men, neither by country, nor language, nor the customs which they observe. For they neither inhabit cities of their own, nor employ a peculiar form of speech, nor lead a life which is marked out by any singularity. Their course of conduct has not been devised by any speculation of inquisitive men; nor do they proclaim themselves the advocates of any merely human doctrine. Inhabiting, as lot may determine, Greek as well as barbarian cities, following the customs of the natives with respect to clothing, food, and other matters, they display to us their wonderful and confessedly paradoxical mode of life. They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share all things with others, and yet endure all things as aliens. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers. They marry, as do all others, and beget children, but they do not destroy their offspring. They have a common table, but not an impure one. They are in the flesh, but they do not live after the flesh. They pass their days on earth, but they are citizens of heaven. They obey the prescribed laws, and at the same time surpass the laws by their lives. They love all men, and are persecuted by all. They are unknown and condemned; they are put to death, and restored to life. They are poor, yet make many rich; they are in lack of all things, and yet abound in all; they are dishonoured, and yet in their very dishonour are glorified. They are evil spoken of, and yet are justified; they are reviled, and bless; they are insulted, and repay the insult with honour; they do good, yet are punished as evil-doers. When punished, they rejoice as if quickened into life. They are assailed by the Jews as foreigners, and are persecuted by the Greeks; and yet those who hate them are unable to assign any reason for their hatred. To sum up all in one word; what the soul is in the body, that are the Christians in the world. The soul is dispersed through all the members of the body, and Christians are dispersed through all the cities of the world. The soul dwells in the body, yet is not of the body; and Christians dwell in the world, yet are not of the world. The invisible soul is guarded by the visible body; and Christians are indeed known to be in the world, but their godliness remains invisible. The flesh hates the soul, and wars against it, though itself suffering no injury, because it is prevented from enjoying pleasures. The world, also, hates the Christians, though in no wise injured, because they abjure pleasures. The soul loves the flesh that hates it, and loves also the members; Christians likewise love those that hate them. The soul is imprisoned in the body, yet preserves that very body; and Christians are confined in the world as in a prison, and yet they are the preservers of the world. The immortal soul dwells in a mortal tabernacle; and Christians dwell as sojourners in corruptible bodies, looking for an incorruptible dwelling in the heavens. The soul, when but ill provided with food and drink, becomes better; in like manner, the Christians, though subjected day by day to punishment, increase the more in number. God has assigned them this illustrious position, which it were unlawful for them to forsake.” How had all this come to pass? No mere “earthly invention” or “human system of opinion” had been committed to them, but truly “God Himself had sent from heaven and placed among men, Him who is the Truth, and the holy and incomprehensible Word, and had firmly established Him in their hearts. He did not, as might have been supposed, send to men any servant, or angel, or ruler in heaven or earth, but the very Creator and Fashioner of all things. Did He send Him for the purpose of exercising tyranny, or inspiring fear? By no means; but in clemency and meekness. As the king sends his son, so sent He Him. As God, He sent Him; as to men, He sent Him: as a Saviour, He sent Him. As calling us, not vengefully pursuing us, as loving us, not judging us, He sent Him. He will yet send Him to judge us, and who shall endure His appearing? Do you not see (the Christians) exposed to wild beasts, that they may be persuaded to deny the Lord, and yet not overcome? Do you not see that the more of them are punished, the greater becomes the number of the rest? This does not seem to be the work of men. THIS IS THE POWER OF GOD.”

FINIS.

___________________________________

[1] Facts seem to be against Tertullian here.