Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 15 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 14: Doughboy White)

_____________________________________________________________________________

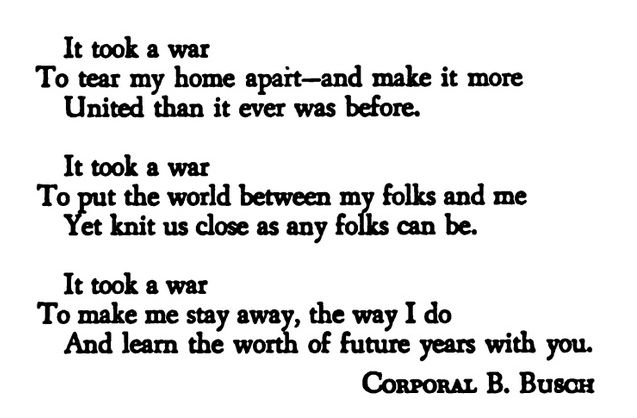

WITH THE 24TH DIVISION ON LEYTE. — At least once each day, some soldier in this front line division loses his wife thru divorce. And every day at least two other men who have been overseas more than 18 months are informed by the War Department their wives have become mothers. On three occasions this year, two men have discovered they were married to the same woman. While between 400 and 500 divorces a year among approximately 15,000 men seems a relatively low percentage, it must be remembered that by far the majority of soldiers are not married. Causes for divorce boil down to this basic reason: the wives have found somebody new.

(from a dispatch by Arthur Vesey, Chicago Tribune Correspondent.)

____________________________________________________________________________

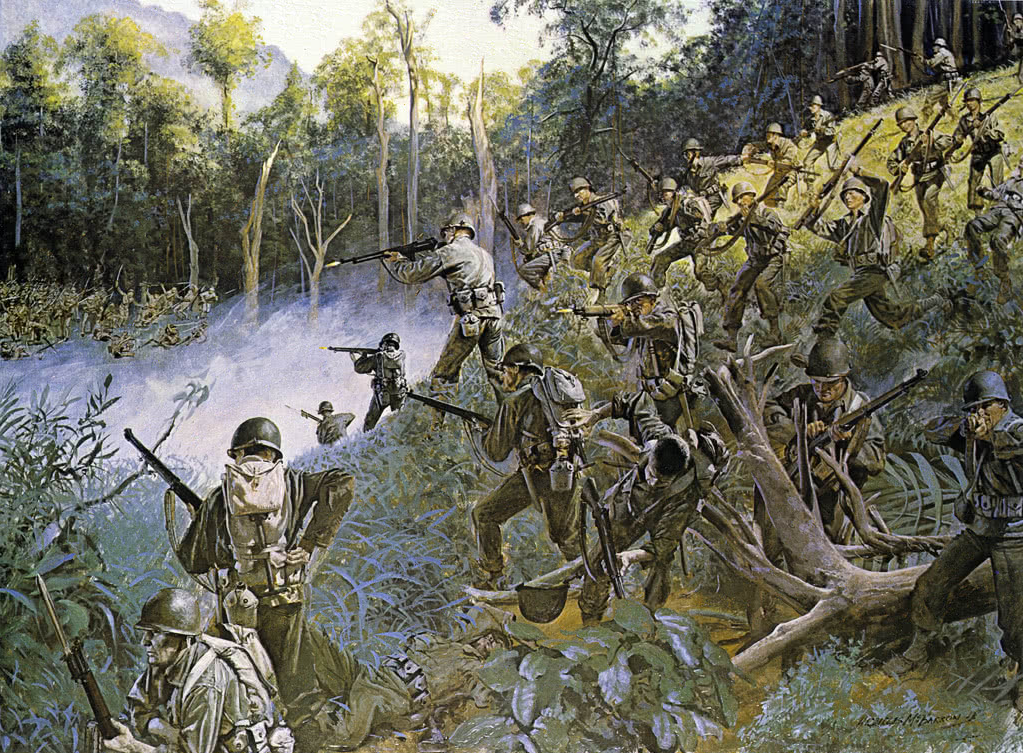

Five hundred and sixty Americans met a test of loyalty on wild and lonely Kilay Ridge. Three hundred and fifty came back whole. Through twenty-five days of hardship and death not one wavered in courage and faith.

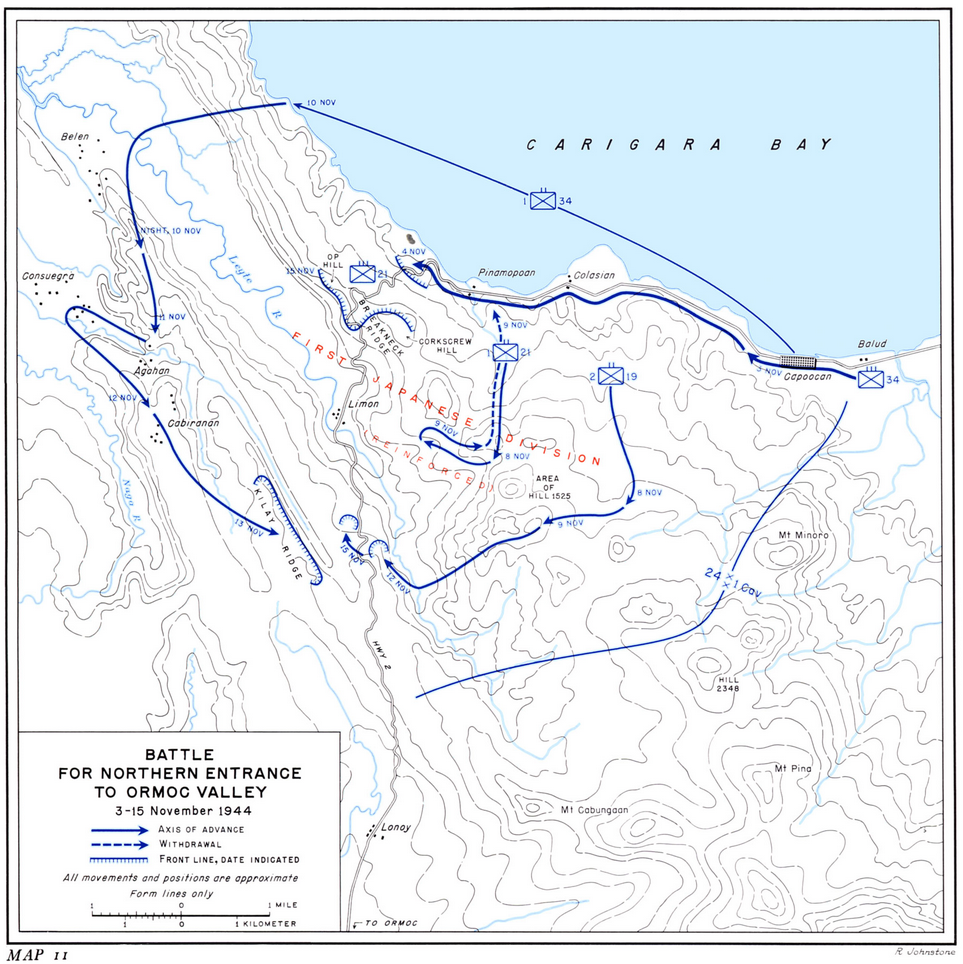

On November 9, before the final breaking of Breakneck Ridge began, the Division’s planners asked themselves, “Where will the Japanese make their next big stand after we have driven them from Breakneck Ridge?”

Aerial photographs showed a long massif of dominating ground four thousand yards south-west of Breakneck Ridge. Geographical maps merely showed a void, with the headwaters of the Naga River springing from this void. Native mountaineers called it Kilay Ridge.

The Division Commander pointed at mist-shrouded Kilay Ridge. “There,” he said. “We must deny Kilay Ridge to the enemy before he can fall back on it. Seizure of Kilay Ridge will disorganize his entire rear. Clifford, you do it.”

Tall, stalwart, adventurous Lieutenant Colonel Thomas E. Clifford nodded. It was a job to his liking. Through the West Virginian’s rugged, easy joviality his eyes shone steel-hard. He alerted his battalion, the First Battalion of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment.[1]

The battalion left Capoocan at dawn, November 10, in eighteen amphibious tractors. It was accompanied by a party of artillery observers. The “Alligators” skirted the coast and made an uncontested landing seven miles to the northwest. The battalion pushed up a stream which flowed under a somber tunnel of vegetation, drove inland and reached Hill 827 by noon. After a brief rest the force thrust through unexplored wilderness, counting progress in yards per hour, guided by one of the many tributaries of the Leyte River. By nightfall it bivouacked on a ridge over looking the river south of the barrio of Helen. Roving patrols found no trace of Japanese.

The order for this mission had come suddenly. His battalion reduced in strength to 560 men by twenty-one days of fighting, Colonel Clifford had summoned even cooks and truck drivers to join the expedition. All vehicles had been left behind. Equipment had to be hand-carried. The battalion’s anti-tank guns had been left in Capoocan; anti-tank gunners were employed to carry lighter weapons and ammunition. “Dog” Company — the heavy weapons team — had left behind two-thirds of its machine guns and mortars. Its hands were needed to carry ammunition for the few guns and mortars taken on the trek. Rations carried by each man were reduced to a minimum. Food, in an emergency, may be found in the jungle; ammunition never. Maps were soon discovered to be violently inaccurate, and Clifford was forced to rely on the haphazard knowledge of native pathfinders. The terrain was the same wildly broken, dimly trailed, desperately overgrown country which faced other units fighting south of Carigara Bay. The tangle of ferns and vines was house-high. The weather was a nightmare of rain and fog.

A ration drop was scheduled for the morning of November 11. But the hills and jungles were blanketed by dense mists. Unable to find the battalion, the transport planes returned to their base.

That day the column forded the Leyte River and seven tributaries of the Naga River and set up a perimeter near a barrio named Agahang. The soldiers spent the evening foraging for wild bananas and breadfruit. Pencils, belt buckles and odd coins were swapped for chickens, potatoes and rice. The forest dwellers were astounded to see Americans. In three years they had barely seen a Jap.

On the morning of November 12, in a pouring rain, the planes identified the battalion’s position by the red and yellow smoke from chemical grenades. The planes dropped food and supplies and the column pushed on across a dozen streams and bizarre mountain country to a point two miles south of the village of Consuegra. Simultaneously a force of amphibious tanks skirted twenty-five miles of rugged shoreline and churned up the Naga River. They brought more rations and ammunition. Patrols reconnoitering in native canoes found that the maze of streams defied navigation above Consuegra. At the latter point a supply base was established on the river’s edge.

On this day Colonel Clifford was contacted by an officer of a guerilla battalion operating in the mountains.[2] The guerilla leader oriented Clifford about his own position and that of Japanese forces guarding the western flanks of the Ormoc Valley. During the later stages of the mission this guerilla force fought bravely to secure the battalion’s rear.

Among native volunteers there appeared a husky, middle-aged Filipino. He was barefooted and he wore a battered straw hat. Slung over his shoulder he carried a primitive shotgun. “I want to speak to the American commander,” he said.

“What can I do for you?” asked Clifford.

“I want to help. My name is Kilay.” “Kilay?” The native nodded. “I am the owner of Kilay Ridge,” he said. “I know it as I know the lines of my hand. The Japanese have set a price on my head. Now I shall go back with you.”

“Fine,” said Clifford. After that they called him Joe Kilay. He was a first-class guide. He fought shoulder to shoulder with the battalion’s men — until a sniper’s bullet pierced his chest. “Joe” Kilay, Patriot, lies buried now in the lonely American cemetery on Kilay Ridge.

On November 12, Sergeant Donald P. Mason of Frame, West Virginia, led his platoon to occupy a wooded hill. No one expected to find Japs on the hill. But sudden machine gun fire stopped the platoon’s right flank. Mason quickly sized up the situation. He told the men on the right to lie tight and to reply the fire. Then he crossed over to his two squads on the left. These he led in a charge to the hilltop.

The Japanese immediately counter-attacked with superior numbers.

“Keep the bums off this hill,” ordered Mason.

Three times the Japs attacked; three times they were repulsed with bayonets and grenades.

On November 13, Colonel Clifford split his battalion into two forces. They moved against Kilay Ridge over separate routes. Their advance was swift and quiet. They occupied all dominating features of the ridge without a fight. The top of the ridge was studded with prepared defenses. But not an enemy was in them. It was clear that the Japanese had intended to use Kilay Ridge as a bastion for their further defense of the Ormoc Valley. Clifford’s force had caught them completely off guard.

Kilay Ridge is three miles long. Its southeastern tip lies three thousand yards south of the town of Limon. The top of the ridge towers nearly a thousand feet over the Ormoc Road. It is very narrow in some of its portions, with cliff-like sides and jungle-covered precipices, but in places its crest widens to about four hundred yards. The top of the ridge is broken into a series of knolls which delighted the artillery observers. For fifteen miles the Ormoc Valley lay open to their gaze. The Ormoc Road, one thousand yards to the east, was visible in places; but elsewhere other ridges between Kilay and the highway obscured the view. Colonel Clifford decided that it was imperative to prevent the enemy from seizing these intervening ridges. Only then could complete support be given to friendly forces driving south from Breakneck Ridge.

On November 14, the battalion transformed Kilay Ridge into a fortress miles in the enemy’s rear. Each company and each platoon was assigned its section of the massif. The summits of the knolls were organized into strongpoints. Trails crossing the ridge were blocked. Reconnaissance patrols ranged near and far to assemble a picture of Japanese positions. Preparations were made for artillery concentrations upon likely avenues of enemy approach.

Scouts were dispatched in an attempt to contact Colonel Spragins’ “lost battalion” at the Ormoc Road block — without success.

Then Clifford called for volunteers among his men to conduct carrying parties of Filipinos to and from the jungle supply dump at Consuegra. Champion among these guides was to be Corporal Lawrence DePaolo, a truck driver from Lodi, New Jersey. On five occasions DePaolo led food and ammunition rains over many miles of extremely difficult terrain controlled by enemy forces.

By the end of the day the Japanese something was amiss on Kilay Ridge.

Toward evening artillery fire struck the battalion’s perimeter. Though rain water half filled the foxholes, Clifford’s men ducked low. Through the thunder of shell explosions they listened to the distant rumble of an artillery barrage pounding Breakneck Ridge, far to the north.

Before dawn, battalion outposts heard distant shouting which seemed to come from the direction of the Ormoc Road. And there were the sounds of digging.

“Moles,” muttered Clifford, “busy yellow moles.”

A combat patrol pulled out to investigate a ridge rising between the battalion’s position and the road. They found a company of Japanese. The Japs had dug in there during the night. The patrol slew five sentries and then withdrew to report its findings. Papers taken from the dead showed them to be members of the First Imperial Division. Their ridge position was henceforth known as “Mole Ridge.”

Later, other patrols by-passed Mole Ridge. They pushed through to the Ormoc Road. They found no trace of Spragins’ roadblock battalion. But they observed a disorganization of traffic on the road which told them that Spragins’ men were busy, if unseen.

Not much happened that day. On Kilay and on Mole Ridge the opposing forces sat in mud and eyed each other through a universe of rain.

November 16 was a day of combat patrols. The Japanese knew that Kilay Ridge was in American hands. They massed forces to eliminate the intruders who were a deadly threat to an eventual retreat from Breakneck Ridge. Both sides dispatched spear heads to feel out the enemy’s strength.

A patrol led by a cook, Mess Sergeant Jose Carrasquillo, from Long Island City, penetrated boldly to the crest of Mole Ridge. It found the ridge clear of Japs. But Carrasquillo discovered an other ridge, eastward of Mole Ridge, and somewhat lower. He observed Japs diligently digging emplacements on this second ridge, which overlooked the Ormoc Road. Carrasquillo named it “Busyman’s Ridge.” Then the cook returned to Kilay Ridge and reported what he had seen.

Meanwhile the company chewed K-rations.

Colonel Clifford dispatched a task force to seize Mole Ridge. It occupied the crest and dug in. In turn it sent a lesser force toward Busyman’s Ridge. A sharp fire fight developed. The second force fell back on Mole Ridge, leaving one of their own dead and carrying seven wounded.

A third spearhead then by-passed Busyman’s Ridge in another attempt to contact the roadblock battalion. This was not successful. Several other patrols sent out on the same mission also failed to find Spragins’ beleaguered force. All patrols reported fire fights with Japanese detachments guarding the Ormoc Road.

A day later, shortly after dawn, a “Dog” Company patrol cut through jungle in a wide arc to determine Japanese strength on Busyman’s Ridge. It was trapped by two Japanese counter-patrols. After a brief and unequal fight it was forced to scatter in a swamp-filled ravine. Only three of the scouts returned: a critically wounded soldier carried by his two comrades. The others were missing and were never heard from again.

Hostile artillery fire falling into the battalion perimeter indicated the presence of a hidden enemy observation post overlooking the American positions. Sergeant Frank Huber, of Milwaukee, led a patrol to ferret out the observers’ perch. They crossed two streams and then they came upon an uncertain trail. The trail twisted uphill to a ridge some 1,500 yards from their own positions.

A scout said, “Look!”

Through the undergrowth, parallel to the trail, ran a telephone wire. The insulation of this wire was rust-red.

“Jap wire,” said Huber. “Let’s follow it.”

They left the trail and crept through the brush, following the wire. The wire led into a little clearing. At the edge of the clearing ten yards away squatted a Jap. The Jap was armed with a machine gun and he was peering down the trail.

The scout unleashed a single shot from his Garand. The Jap dropped dead.

“Sit still,” whispered Huber. “There must be more around than one.”

They waited in silence. Nothing happened. Huber’s eyes followed the telephone wire across the clearing — and saw that it seemed to lead into the ground near the gnarled base of a tree. Then he saw something else; he saw a muddy piece of canvas flapping in the wind squall.

Huber crept into the clearing to investigate the canvas. His comrades held their breath. They lay in wait, covering their leader.

Frank Huber found that the canvas was part of the camouflage of a Japanese position. He motioned his patrol forward. They surrounded the canvas. Upon signal they yanked it aside.

There were four holes, and there were two Japs in each of the holes. The Japs sprawled in the mud. Two of the eight wore officers’ insignia. Nothing moved. The eyes of seven of the Japs were closed. Only the eyes of one were open in a lifeless stare.

A soldier picked up a handful of mud and threw it into the face of the Jap whose eyes were open. The eyes blinked. Instantly every man of the patrol blazed away into the holes. There was an agony of writhing and yelps and then the shooting ceased and there was only a fading moan. The largest of the holes contained the end of the rust-red wire and a telephone.

Later that day, two companies attacked Busyman’s Ridge. There were two hundred Japs entrenched with rifles, machine guns, mortars and artillery. Fifty-six Japanese were killed. Meanwhile, another force of Japanese counter-attacked from the flank and “Baker” Company was cut off from the battalion.

When darkness fell, “Baker” Company was still surrounded. Its commander reported a number of wounded. Three Japanese machine guns were firing into its tight perimeter on Busyman’s Ridge. The knolls and canyons between it and Kilay Ridge were loud with the crackling of snipers’ rifles.

Clifford called for volunteers. He himself was first to respond to his call. He led the volunteers in a thrust to “B” Company’s perimeter on Busyman’s Ridge. The firing continued unabated. Clifford assembled the wounded and proposed to carry them back to Kilay Ridge. There an aid station had been established. In the treacherous terrain four men were needed to carry each of the disabled soldiers in relays. The company commander protested that he could not spare so many men if he were to hold the ridge through the night. Clifford thereupon freed four of the litter bearers for combat.

“I’ll carry one of the boys,” the colonel said.

With that he hoisted a wounded private on his back and led his relief party through a mile of rain forest and sniper fire back to Kilay Ridge.

A battalion lineman, Technician Thurlow Rice of East Booth- bay, Maine, heard a wounded soldier cry for help. Hostile machine gun, mortar and rifle fire raked the area. An aid man dashed by in the direction of the cries for help. Rice climbed out of his foxhole to help the aid man carry the wounded soldier to cover. While they lugged their comrade through thickets, the corpsman gave a grunt.

“What’s the matter?” asked Rice.

“I’m hit,” the corpsman said.

“Jesus Christ,” said Rice. “Keep still and let me help you.”

Bullets whined through the jungle. There was the flash and crash of mortar shells bursting in the treetops. Rice was down on his knees, working over his two wounded comrades. The aid man muttered instructions. Rice followed the instructions. He disinfected the wounds and bandaged them and the wounded were ready to be moved.

The corpsman said, “There’s another wounded guy somewhere. I heard him groan.”

Rice crawled through the underbrush until he had found the groaning man. He bandaged him and gave him sulfa and dragged him to the spot where the corpsman lay with the soldier who had been hit first. Just then a long burst of machine gun fire struck among the group. One was killed outright. Another of the wounded was hit three times. A second corpsman rushed forward and Rice helped him to carry the survivors to cover. Thurlow Rice was loyal: loyal to his buddies, to his country, to his wife, Katherine. Death took him a few months later.

In the gray morning of November 18, all machine guns of the battalion were moved from the perimeter to give supporting fire for an attack on Busyman’s Ridge. Patrols pushed forward by Captain Edger W. Rapin of Bensenville, Illinois, “Dog” Company’s commander, surprised a detachment of twenty-five Japs. The Japs were cooking over two fires. Volleys from Garands ended their breakfast. Seventeen were killed and the survivors scattered in all directions.

But a reconnaissance patrol led by Captain Rapin was ambushed by an enemy force of superior strength. In the first flash of bullets the lead scout died. The second scout fell wounded less than ten yards in front of the ambush — holes dug under the immense trunk of a fallen tree. Machine guns chattered and rifles cracked and nothing could be seen of the firers. The patrol deployed in a skirmish line and held its ground.

Captain Rapin saw that the wounded man was unable to move out of the path of fire. Flat to the ground, the captain crawled forward to rescue his scout. He reached the side of the scout and began to drag him toward a hollow in the ground. Then machine gun bullets struck. The disabled scout was hit again. Captain Rapin was hit.

The wounded captain struggled in desperation to pull the scout to the rear. His own strength was dwindling with the loss of blood. Then he saw that the scout was already dead.

A young Texan, Corporal Arlton Brower, of Avery, now took command of the patrol. He maneuvered the survivors to a spot from where they could fire on the ambush from three yards distance. Captain Rapin was rescued. Corporal Brower then made two attempts to bring back the bodies of the scouts. Sprays of hostile bullets drove him back.

The battalion attacked. Fifty-three Japanese met death. “Charlie” Company relieved “Baker” Company on Busyman’s Ridge. “Dog” Company was embroiled in machine gun and mortar fights throughout the day. Two of its corpsmen — dirty, wet and tired as they were — attained the peak of “gallantry in action.”

One was Technician Otto Kirchner-Dean, the adopted son of Reverend Dean of Kingston, New York. Kirchner-Dean saved three wounded men from death. One of the wounded was so hopelessly smashed that the corpsman hesitated to move him. Under machine gun fire the corpsman administered two plasma infusions. The wounded soldier lived.

The other corpsman was Sylvester Davis of East Aurora, New York. Japs threw grenades at him as he crawled forward to rescue a comrade. Davis was wounded in the thigh. But he crawled on, leaving a trail of blood, and he pulled the other man to cover.

Private Frank Falbo of Colver, Pennsylvania, had mounted his machine gun behind a log. He was firing steadily at a Japanese position he could not see. His observer on the slope below the log was shot through the hip. The observer shouted for help. Falbo fired another long burst in the direction of the Japs. Then he jumped over the log and rushed down the slope. He quieted the wounded man and after that he carried him to the shelter of the log.

All through the night enemy artillery fire fell into the perimeter on Mole Ridge. Scattered shells harassed the men on Kilay Ridge. The explosions denied them much needed sleep. A steady rain fell.

Silent men dug new graves in the battalion cemetery.

In the bleak dawn of November 19 the Japanese made their first major bid to recapture Kilay Ridge. The attack came at 7 A.M. It struck the battalion’s flank with ominous force. In their assault waves the Japanese carried light machine guns and mortars. “Baker” Company’s platoons met the brunt of the onset. The Japs attacked with massive fury. Through seven mad hours their charges followed one another like waves lashed by a typhoon.

By 9 A.M. two heavy machine guns had been knocked out of action. The perimeter showed gaps. At this time Japanese detachments began a flanking movement to the right. The battalion’s artillery observers crawled to hidden perches in the onrush and directed shellfire by radio.

By noon “Baker” Company was surrounded and desperately in need of ammunition. Two soldiers volunteered to break through the howling ring of Japs. They were Private Fred Finke of Scottsbluff, Nebraska, and Private Richard Batkies of Quinton, Virginia.

They crept out of the perimeter and slipped through the enemy line, crawling for stretches, rushing from thicket to thicket, lying motionless when Jap assault groups stormed by. They pushed to a knoll where “Able” Company protected the other side of Kilay Ridge. There the two volunteers were greeted with the bark of Garands.

“Don’t shoot,” yelled Finke. “We are Americans.”

The firing stopped and a sullen voice said:

“The hell you say. Who’s your officer?”

‘Tom Rhem,” Finke yelled. “Company ‘Baker.’ “

“Okay,” the voice said. “Come in.”

Soon they left “Able” Company’s line, each loaded down with a hundred pounds of ammunition. They arrived at their own unit while the heaviest Jap attack of the day was under way. Fred Finke collapsed, killed by Jap bullets. Richard Batkies ran along the perimeter, distributing ammunition to the men in the foxholes. Then he returned to his dead comrade. He stared at him as if in mute apology. He picked up Finke’s load of ammunition, and again he ran the length of the foxhole line.

On the embattled perimeter an automatic rifle gunner decided to change his position to a spot which would give him a better field of fire. He slipped from hole to hole and then a Jap machine gun sent a burst of slugs through his belly. In a foxhole a little distance away lay Lieutenant Russel Pyle of Newark, Ohio. All day, between fire from his carbine, Pyle had encouraged the men to his right and left. He heard the wounded B.A.R. man scream. He also saw bullets knife into the muck two feet away.

Keeping close to the ground, Pyle inched out of his hole. He dragged the wounded man back into the foxhole and dressed his wounds and covered him with a poncho and that was all that could be done for him. The soldier begged for water; but water cannot be given to men with belly wounds. Russel Pyle picked up the dying gunners’ B.A.R. He used it with determination.

Inside the perimeter Corpsmen Duncan Stewart and Michael Murphy patched up all casualties who still could crawl. After first aid was given them, the wounded men crawled out of the battle zone under their own power. Stewart and Murphy then plunged through mortar bursts and rescued other wounded who had been lying in the firing lines. As they were carrying back one of the wounded, Corpsman Stewart was hit. Now Murphy worked alone, and he saved them both.

Colonel Clifford prowled about the front to reconnoiter. To ward 2 P.M. he ordered “Baker” Company to fall back a hundred yards to the north and hold there. He reinforced it with “Able” Company teams. Lieutenant Pyle directed the withdrawal. He coolly made the rounds to assure himself that no wounded man, nor weapon, nor supplies were left in the abandoned perimeter.

But there was Sergeant Raymond Kowski of Waterloo, Wisconsin. In the withdrawal Kowski was looking for a friend who had been hit earlier that day. He could not find him. Alone, in loyalty and desperation, he turned back. He ran into the abandoned perimeter to find his wounded friend. He raced along the line of empty, muddy, often blood-stained holes. There was no one in sight. There were only the sounds of Japs scrambling through the undergrowth. Kowski returned on the verge of sobbing.

On the battalion’s field map the abandoned knoll bears the name “Easy Hill.”

“Loss of manpower was due not only to battle casualties, but to the attrition of weather, terrain and climate upon the battalion. The weather was a constant adverse factor. The Ridge surface became a slick mass of mud and slime. Troops could seldom get dry. They had come on foot, carrying all supplies over uncharted terrain, which taxed their strength to the limit. Rations had been meager, and sleep fitful in sodden holes interrupted by outbursts of sniping and artillery fire. Under these conditions men were unable to properly care for themselves and contracted foot ulcers, dysentery and fevers. Colonel Clifford ordered the battalion surgeon to evacuate only the worst cases, leaving the others to fight with what strength remained them, and often on pure guts.”

(from the Division Record)

Clifford felt that every fit man would be needed to defend Kilay Ridge. Before dawn of November 20, he ordered “Charlie” Company to abandon Mole Ridge and Busyman’s Ridge. The withdrawal was accomplished without the knowledge of the Japanese.

After daylight a mass of Japs charged Mole Ridge. They found it empty of Americans, but straddled by bursting American artillery shells placed there at Clifford’s request. An artillery barrage was also laid on the southern reach of Kilay Ridge (“Easy Hill”). The battalion’s observers had crawled to points about one hundred yards from the zone of explosions. But the rain blotted out all visibility. The observers adjusted artillery fire entirely by sound.

At 1 P.M. “Baker” Company attacked Easy Hill to drive the Japs from their toehold on Kilay Ridge. The thumping of mortars paced the infantry charge. “Able” Company, only sixty strong, assaulted a height to the rear of Easy Hill. The attack met heavy gunfire and a curtain of shells from 90 millimeter mortars which had hitherto not been seen in action. The assault units were driven back, and the Japanese counter-attacked.

Private Jesse Harris, a corpsman, of San Jose, California, crossed the zone of mortar bursts to rescue a wounded soldier. He went out a second time to save the life of a fellow aid man who had been cut down by shrapnel.

Corpsman Leo McDonnell of White River, South Dakota, had his foot smashed in action. All the same he dragged himself through the scorched thickets to render first aid to the wounded.

Sergeant Donald Watson of Lewis, Iowa, was badly wounded. He did not give up. He remained with his platoon through two perilous hours until a Jap onrush was repulsed.

Private Nelson Coder of Chanute, Kansas, was hit twice that day. He remained in his foxhole and kept his submachine gun blazing until he was relieved and ordered to the rear.

When darkness came, Japanese machine gun fire into the perimeter became so murderous that “Baker” Company’s men lay flat in the mud, unable to dig their holes for the night. Sergeant James McFarland of Lexington, Kentucky, crawled to an unprotected rise in the ground to direct mortar fire on the enemy guns. In rain and darkness he could not see a thing. He stood up then, to see better. He now saw the red muzzle flashes of the guns, and he told the mortarmen where they should lob their shells. In the fiery fans of exploding shells the Jap gunners ceased firing. They moved away their guns. Now “Baker” Company could dig in. They called for McFarland. There was no answer. James McFarland lay dead in the rain.

Through saturnine jungles trudged a party of artillery observers under the command of Lieutenant James A. Waechter of St. Louis. Darkness overtook the group on the banks of the Naga River. Waechter decided to stop for the night. The men dug shallow foxholes some fifty feet from the west bank of the river.

The night was full of clouds and as dark as the inside of a tomb. There were occasional sheets of lightning, and fireflies meandering among the black barricades of vegetation, and there was the dull croaking of some night bird. No firing disturbed the night.

Waechter did not sleep. The earth beneath him was saturated with moisture. He lay under his poncho and listened to the thin humming of mosquitoes and to the distant growl of an airplane’s engine. He thought of home, of the fighting and dying on Kilay Ridge, of the war and whether the whole agonizing mess would do humanity one whit of good. The hours were long and James Waechter looked at his watch.

It was 3:45 A.M. Nearly three hours until dawn.

A shrill cry stabbed through the night like an invisible rocket. It was a cry different from men’s dying cries in battle. Waechter flung aside his poncho and reached for his carbine and pressed the safety release and listened. No shots were fired. No outcries followed the first. But there were strange gurgling sounds and then there was a loud splash.

Now Waechter was on his feet. He found one foxhole was empty, one man missing. The others searched the ground and the thickets. No trace of the missing man could he found.

With daylight they searched again. They scoured the ground for tracks that might give a clue to the vanished soldier’s whereabouts. They found the man’s rifle at the edge of the river. They found tracks in the mud ajong the river’s edge. A guerilla scout studied the tracks. “Crocodile,” he said. “Crocodile come to fox hole, drag boy into river.”

The morning of November 21 was quiet. A patrol reported that Japanese were digging new emplacements around Kilay Ridge, apparently for reinforcements.

At 2:30 P.M. scouts sighted two strong columns of Japanese converging on the battalion from south-east and north-east. Clifford dispatched a rifle platoon to the northern end of Kilay Ridge to keep open the supply line from Consuegra.

In the late afternoon a transport plane droned low over the ridge. With fine precision it dropped ammunition, a batch of dry blankets, and litters for the wounded.

The Japanese attacked again at dusk. Their charge swept around “Baker” Company’s perimeter and struck a position held by an “Able” Company platoon. The platoon commander, Sergeant Donald Mason, directed the fire even after his hand had been chewed up by shrapnel. Another sergeant, Forest Clark of Webster, Kentucky, plunged through the jungle to bring reinforcements to his now encircled platoon. He saw a Japanese leap out of his path and behind an ironwood tree. Following the rule of “aiming at the middle of what you can see,” the Kentuckyman fired. His bullet penetrated the tree trunk and nailed the Jap. But Forest Clark was wounded. He staggered on through the soggy pulp of ferns and rottenness, bent on the completion of his mission. He half slid, half fell down a jungled incline and came face to face with a Japanese patrol wading along the gravel bottom of a stream. The sergeant knew well the simple sequence of jungle combat: You see nothing; you suddenly come face to face with the enemy; the winner is he who scores the first hits. No one really knew what happened, except that Forest Clark was killed before he could bring aid to his platoon.

“Dog” Company’s heavy mortars pounded to break up the attack. Closest observation was needed to keep the high explosive shells from falling on friendly troops. Sergeant Guy Brown of Bloomfield, Kentucky, volunteered to do the job. He muscled to the flank of the enemy onslaught. The mortar shells fell clean and true.

The Japs discovered the observer in the brush. They sent snipers to destroy him. Brown dodged the snipers. He continued to direct the doings of the mortars. The assault was broken and repulsed. Guy Brown died later of wounds received in battle.

During the fire fight a man was hit and lost his mind. Hands pressed to his wound, he ran about the perimeter, a target to the Japs and an obstruction to the fire of riflemen around him. Corpsman Alfred Smart from Camillus, New York, saw the danger. He sprang out of his hole and pressed the wounded soldier to the ground. Slowly, speaking soothingly, he moved the other to the shelter of a mound of muddy earth. Then Smart discovered that he had left his first aid kit behind.

“I have to get my medicines,” he said. “Will you stay quiet now and not get up again?”

The wounded soldier stared at Smart. He said nothing.

“Will you stay down now? Or do I have to tie you up?”

“I’m all right now,” the other mumbled.

Again Smart crossed the fire-swept perimeter. He retrieved his kit. He bandaged the wounded man, gave him morphine and sulfa, and then surrendered his poncho to keep him warm and safe from the effects of shock.

That evening more graves were dug on Kilay Ridge. The chaplain’s voice was clear and sad.

Look at your fabric

Of labor and sorrow.

Seamy and dark

With despair and disaster,

Turn it— and lo,

The design of the Master!

At daybreak of November 22, Colonel Clifford ordered patrols to probe north and east to test Japanese strength across the battalion’s supply line. The patrols discovered an ambush athwart the trail from Consuegra. They ambushed the ambush and then blasted it with machine gun fire. Eleven Japs were killed.

Except for continuous sniping, the day was quiet until late afternoon. “Baker” Company was immobilized by heavy Japanese fire. The fire came from three sides. At the same time a Banzai assault struck “Able” Company’s perimeter.

The ferocity of the attacks grew as dusk approached. At 6 P.M. five hundred Japs charged “Able” Company with bayonets and grenades. Their unearthly screaming rang through the jungle and the dripping kunai. It was as if every bush and grass blade and tree stump had joined the pandemonium. By all tactical rules a situation such as developed would call for a fighting withdrawal. But Colonel Clifford had orders to hold Kilay Ridge “at all costs”— and hold it he did.

By 8 P.M., “Baker” Company again was completely surrounded. It was ordered to break out and fall back to the rear of “Able’s” line. The company had lost an officer and two sergeants. There were many wounded. A successful withdrawal was made possible only by a covering wall of machine gun and artillery fire, and by the audacity of Lieutenant Thomas Rhem of Memphis, Tennessee and his platoon of riflemen.

Rhem radioed the isolated company to duck low. He lined up his men. He had them fix bayonets and he gave each man three grenades. They pulled the pins and hurled their grenades in quick volleys. Then they stormed forward with Rebel yells.

It worked. The platoon pierced the Japanese block. A few of the enemy were caught huddled in the darkness, praying. Rhem’s “Banzai” platoon killed twenty-five Japs in the charge. It captured five machine guns. And not a man was wounded.

But a litter train of wounded heading for safer ground was ambushed. One wounded soldier was killed.

Private Oronzo Scarcella of Hazelton, Pennsylvania, trotted from foxhole to foxhole. He bandaged four wounded men under fire and then mobilized a squad to carry them to cover. After that Corpsman Scarcella heard that an outpost outside the perimeter had been hit. He made his way through Japanese assault waves and pulled the outpost to safety.

Corporal Paul Lyons of Thomaston, Connecticut, volunteered to act as a litter bearer in the withdrawal. Thus burdened he knew full well that he could not defend himself against attack. The injured man whom he carried was saved. But Paul Lyons was killed by enemy bullets.

The attacks continued into the night. Rain squalls hit Kilay Ridge. The situation became so serious that “Dog” Company’s heavy mortars laid a protective barrage yards in front of “Able” Company lines. The indomitable Clifford ordered that ammunition and supplies be hidden in thickets and gullies so that they would not fall into enemy hands in the event of a break-through.

While the evacuation of the wounded was in progress, a Japanese machine gun fired down a black jungle trail. The evacuation party was forced to cross this trail. Sergeant Oliver A. Young of Carlisle, Arkansas, set out to liquidate the Jap gunners. The six-foot-four former University of Arkansas athlete crawled parallel to the trail in the direction of the gun flashes. He found the machine gun dug in behind a big molave tree.

Young snaked his way up the opposite side of the tree. He made sure that he kept the trunk between him and the spears of fire. Then he stood up and pulled the safety pin from a four-second grenade. He reached his long arms around the tree. He counted:

“One dead Jap… two dead Japs…”

With that he let go the grenade. It exploded before it reached the bottom of the hostile nest. Fragments and shreds of human flesh spattered the base of the tree.

Fragments slashed the Arkansan’s forearm….

Through the confusion of night fighting Lieutenant Thomas McCorlew of Cleveland, Texas, was searching for “Able” Company’s command post. In the blackness of the downpour he bumped into another man. McCorlew put his hand on the man’s shoulder. “Say, Buddy,” he whispered. “Where’s ‘A’ Company?” A startled Jap wheeled and vanished. McCorlew fired — missed.

Clifford thanked his stars that the Japanese command did not press its attacks on November 23.

The battalion was licking its wounds.

There was an attack at 8:30 A.M., but the enemy appeared to have lost morale in the past days’ slaughter. The charge collapsed in mortar fire, which was expertly directed by Staff Sergeant Lester Winkler of Perryville, Missouri.

That day the planes came and two bundles of supplies floated into the battalion position. Japanese observers spotted the place. Machine gun fire and artillery shells furrowed the perimeter.

A patrol pushed through Japanese lines to report the battalion’s predicament to the commander of the division driving south from Breakneck Ridge.[3] On the return trip to Kilay Ridge the patrol was cut off. At the same time it was driven to seek cover because friendly artillery bombarded the surrounding Japanese concentra tions. But led by Fulton Brightwell of Burley, Idaho, a scout, the patrol reached Kilay Ridge after an adventurous ten-hour trek across far mountains. The message it brought back to Clifford said, “Hold fast.”

At dusk enemy reinforcements were observed digging in east of the besieged battalion’s lines.

“A strength report of the battalion as of 23 November showed the following men and officers present for duty: “A” Company, three officers, sixty-two enlisted men; “B” Company, four officers, seventy- one enlisted men; “C” Company, four officers, seventy-five enlisted men; Headquarters and attached personnel, six officers, seventy-one enlisted men.”

(from the Division Record)

For two days, except for patrol activities, sniping, and intermittent harassing fire from artillery and automatic weapons, Kilay Ridge was quiet. There were skirmishes on the battalion’s southern flank. But there was no dangerous offensive action.

On Thanksgiving Day a sickly sun glowed through a pall of clouds. A faint patchwork of light and shadow appeared in the ceiling of jungle and kunai. The men looked at the ghost of the sun, and some of them had tears in their eyes. It was as if a ray of hope had filtered into their terrifying loneliness on Kilay Ridge.

In the evening twilight of November 25, “Able” Company’s sector was savagely attacked with machine guns, mortars and artillery. The assault was repulsed through the quick thinking of an artillery observer. Lieutenant James Waechter rushed to an exposed knoll which gave him observation of the attacking force. He swiftly adjusted a counter barrage.

An enemy shell exploded nearby. The blast tore Waechter’s aid limb from limb. It blew the observer some distance down the slope. Waechter groped, feeling for his bones. Badly shaken, he crept back to his post. He radioed directions until the attack ebbed away in failure.

On November 26 a swarm of Japs dug in astride the supply trail from Consuegra. These Japs were routed in a fire fight by combat patrols.

“On that day Colonel Clifford estimated that a minimum of one reinforced enemy company was operating on his south; at least two reinforced companies on a ridge one kilometer to his east; and a strong but unknown force of enemy troops on the west. If the western force pushed northward, the battalion’s route of withdrawal would be cut off.

“Artillery fire fell into the perimeter throughout the 27th. A patrol from the 128th Infantry arrived to report that reinforcements were enroute. The question was: would they arrive in time?

” “You don’t have to tell me that we are in a tight spot,’ Colonel Clifford messaged. ‘We know it’ “

(from the Division Record)

In the afternoon of November 27, a massive Japanese assault struck “Charlie” Company’s sector of Kilay Ridge. The fight surged up and down the muddy slopes until the thrust was finally repulsed at 8:30 P.M.

During this battle wire fines between the battalion and “Charlie” Company were disrupted. Two men went out in the dark to restore communication, Raymond M. Davis, of Chatsford, Illinois, and Vincent Lyons of Coronado, California.

Davis was a wire chief, Lyons a lineman. In danger of fire from friendly as well as from enemy troops they sensed their way down a crooked trail. Rain and darkness made it difficult to find the break. While one of them searched the line, the other held a submachine gun ready. They had searched the line for one-half mile before they found the break. Its repair restored communication with the front line where the counter-attack was still under way. They then patrolled the wire line until dawn.

Two other soldiers who worked alone in the dark savagery were Corpsman Stanley Lokken of Beloit, Wisconsin, and Sergeant Bill Kurdach of New York City. Kurdach, surrounded by fire, sat half buried in slime on the forward hillside, an observer for “Dog” Company’s mortar crews. Lokken, who is a family man, abandoned the protection of the foxholes to help the wounded. His night’s work ended only when he was critically hit.

The first enemy attack on November 28 came at dawn. While Japanese. assault detachments pushed up the slope, Jap machine gun fire and mortar bursts belching from another ridge forced the riflemen to duck low in their holes. Sergeant Irving Greenberg of New York City crawled down the slope and onto a bluff from which he could track the progress of the attacking force. By a system of self-devised signals he directed the counter fire of the mortar batteries. The attack broke before it attained the crest.

The second attack came at 10 A.M. After a close-range fire fight it was repulsed.

The third attack struck in the dark, at 7:30 P.M. This was the Japs’ most desperate effort to recapture Kilay Ridge. It began with a barrage of 90 millimeter mortars. The “ashcans” hurtled from the rain-sad sky with the devastating power of artillery. Burning jungle cast flickering light on fountains of mud, roots and branches driven into ragged geysers by the explosions. The ridge rocked and trembled. Men quaked under the horror of the concussions. In four foxholes six men were smashed by fragments. Still, one man remained above ground in the barrage: Corpsman John Honeycutt of Rock Springs, Texas. He darted from hole to hole, patching jagged wounds which mortar fragments make.

At eight o’clock heavy machine gun fire from the east joined the mortar cannonade. Simultaneously another brace of machine guns spouted death from the west. The vicious intensity of this cross fire mounted from minute to minute. Jap assault teams were muscling up a gully on the western side of Kilay Ridge. At the same time a determined attack hit “Charlie” Company from the south. Telephone lines from Clifford’s headquarters to all company positions were cut.

“Dragon Red” fought back. Every mortar in the battalion pumped high explosives at top speed. By 8:15 friendly artillery was pounding all lanes of approach to Kilay Ridge. By 8:30 “Charlie” Company’s squads were in the midst of a bayonet fray with superior numbers of Japanese. By 9 o’clock every man of every unit in the battalion was fighting at close quarters. That was more than a battle for a ridge. It was a battle against annihilation. The night was ugly with flash and crash and cry and blood. Rain fell heavily.

“Dog” Company machine gunners stemmed the twenty-seventh Jap onrush since their machine guns had been mounted on the ridge. Section Leader Jewell Caughlin of Bardwell, Kentucky, urged his crew to do the impossible. Sergeant Frank Falbo of Yorkville, Ohio, singing and cursing, worked over guns that had run hot and jammed, until they functioned again. Private George Meyer, of Brooklyn, fired more than five hundred rounds between dusk and midnight and never said a word. Gunner Michael Crispino of Burkeville, Virginia, poured lead into Japs close enough to be scorched by the muzzle flashes of his killing tool.

By 9:30 the Japanese had driven wedges between the company perimeters. By ten o’clock “Charlie” Company was surrounded.

Private Harry Barnes, whose wife lives in Eufala, Alabama, volunteered to get a communication wire through to the isolated company. Alone, armed with a carbine and a roll of wire, he wriggled away in the dark. He laid four hundred yards of wire through Japanese lines. On the way he heard slurring footfalls in the brush and lay still. A detachment, of Japanese with bayonets on their rifles pounced by. Barnes prayed mutely that none would stumble over the wire athwart their course.

Corpsman John Honeycutt heard bursts of Jap grenades in a thicket and then he heard a drawn-out moan. Bent low, he rushed into the thicket.

He found a soldier ensnarled among the roots. The soldier sensed the nearness of another. He lashed out with both feet.

“Hold it,” Honeycutt muttered. “I ain’t a Jap.”

“Something happened,” the soldier gasped.

Honeycutt ran his hands over the fallen comrade. He found that the man’s arm had been blown off at the elbow. There was the end of a splintered bone and the outpulsing of arterial blood.

John Honeycutt forgot the nearness of the Japs. He forgot the battle and the war and home. In downpour and mud and tumult he worked for four hours. He saved his wounded comrade’s life.

The battle pounded through the night. An hour before dawn snipers’ rifles still cracked like whips swung by lunatics, and mortar fire still fell in intermittent showers. Rifleman Florencio Ortiz, of New York City, thought he heard something creep into the area held by his platoon. Most of the men in the platoon were exhausted from the all-night ordeal. They lay in their holes like men in a trance.

Ortiz sat up. There were three Japanese slinking past his hole. The Japs were carrying a machine gun. Ortiz sat still and listened. There was the sound of Japs crawling all around the platoon position. He sprang up and threw a grenade at the group with the machine gun. Before it burst, he shouted:

“Japs! Japs!”

He fired the eight rounds in his rifle, reloaded, fired again. Shadowy shapes darted in the gloom, crumpled and panted. The platoon was aroused. The attack was thrown back.

Florencio Ortiz was killed in action on Christmas Eve.

“Captain George E. Morrissey (of Davenport, Iowa) commanded the Medical Detachment during operations on Kilay Ridge, Leyte, Philippine Islands, from 10 November to 4 December 1944. During this period, Captain Morrissey, through his selfless devotion, tireless energy and surgical skill, successfully treated and evacuated all of the hundred and one casualties sustained during twenty-four days and nights of conflict. Working under the most difficult conditions, often without food and water, always under fire, Captain Morrissey ran a medical service that was an inspiration to the entire force, and resulted in an alleviation of suffering that can never be adequately estimated. His medical duties often required his exposure to direct fire. Working at night by flashlight, he frequently made himself a visible target, as snipers often infiltrated into the perimeter. Duty Status: Battalion Surgeon.”

(from a Field Citation)

At daybreak November 29, the Japanese were still in force on Kilay Ridge. All perimeters were still under attack. The situation was gloomy, but Clifford was still hitting back.

At 9:20 A.M., lookouts on the highest knoll sighted friendly troops working down the Ormoc Valley from the direction of Breakneck Ridge. Colonel Clifford warned these troops by marking Japanese strongholds in their path with smoke shells from heavy mortars. He followed up the smoke shells with high explosive. The mortar shells, as if bent on some joke, struck two enemy ammunition dumps. The dumps blew up.

At 1 P.M. arrived the welcome word that a relief battalion was slogging toward Kilay Ridge. Combat patrols blasted clear the supply line from Consuegra. Meanwhile, Technician Thurlow Rice of East Boothbay, Maine, and Private Raymond Tingle of Madison, Indiana, crawled through a mile of mucky jungle to repair disrupted wire lines between the ridge defenses. The relief battalion arrived at dark.

On the morning of November 30 the Japanese still held 800 yards of Kilay Ridge. A two-battalion assault swept it clean.

On December 1, Clifford — once an All-American footballer from West Point — received a message from higher headquarters which closed with the following words:

“You and your men have not been forgotten. You are the talk of the island. Army beat Notre Dame 59 to 0, worst defeat on record.”

Clifford grinned like a happy boy. (But he never saw another football game. Just before “VJ-Day” we buried his shell-torn body in the muck of Mindanao Island.)

On December 4, the haggard remnants of “Dragon Red” marched back to the coast. They had accounted for more than one thousand dead Japanese in the fighting for Kilay Ridge. When they arrived at Calubian they were greeted with the news that three thousand fresh Japanese troops had landed on the Leyte Peninsula, near San Isidro, five miles to the west. They ate a meal of fresh eggs, and cursing heaven and earth and their own weariness, they slung their rifles and pulled out to meet that new threat….

Since the Red Beach landings seven thousand three hundred Japanese had died in the Division’s path.

Among its own the Division counted one thousand nine hundred and twenty-nine wounded, or missing, or killed.

(Continue to Chapter 16: Another Half Million Coconuts)

________________________________________

[1] “Dragon”— code designation for the Thirty-Fourth Infantry Regiment; “Red”— code designation for its First Battalion.

[2] First Battalion, 96th (Guerilla) Infantry Regiment.

[3] The 32nd Infantry Division.