Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Triggernometry: A Gallery of Gunfighters, by Eugene Cunningham (published 1934).

He married, but not for him any settling down to the role of peaceful, hardworking husband. In fairness to him, he could hardly do that. The locality was simmering, ready for an explosion. He was a marked man. Your gunfighter is always that. Someone is always scheming to kill him and prove himself the better man.

He went from Gonzales toward the King ranch and killed a Mexican highwayman on the road. The next year, while driving a horse-herd, Wes again fell foul of the law. He remarked of this encounter:

“At Willis some fellows tried to arrest me for carrying a pistol. They got the contents thereof, instead.”

There were old warrants by the sheaf, out against him. But Gonzales County was pretty evenly divided between a secret vigilance committee of carpetbaggers and negroes and the citizens of the county who termed themselves law-abiding. These last were Wes Hardin’s allies. They were strong enough to prevent his arrest. But always there was the possibility of private brawls.

One Sublett quarreled with Wes over a tenpin game. The two swapped lead and Sublett got a bullet in the shoulder, while Wes was almost fatally wounded. His friends nursed him and with the State Police sniffing frantically for his hideout, he was shifted from place to place. At last he surrendered to an officer for whom he had complete respect—Sheriff Dick Reagan. He surrendered because two policemen had stumbled on his hiding-place. From his bed, he had battled these, killing one, wounding the other, and himself receiving a new bullet-hole in his thigh. When Reagan came with a posse, to receive Wes’ surrender, an excited posseman shot at Wes and hit him in the knee.

From the jail at Austin where Reagan first took him, Wes was returned to Gonzales. Here he was permitted to escape custody. He got up and about and celebrated the recovery by a saloon-row with one Morgan. He killed Morgan. The carpetbaggers’ committee was hand-in glove with Sheriff Jack Helms. Wes heartily disliked Helms and after some quarreling, the trouble ended in the smoke—with Helms dead.

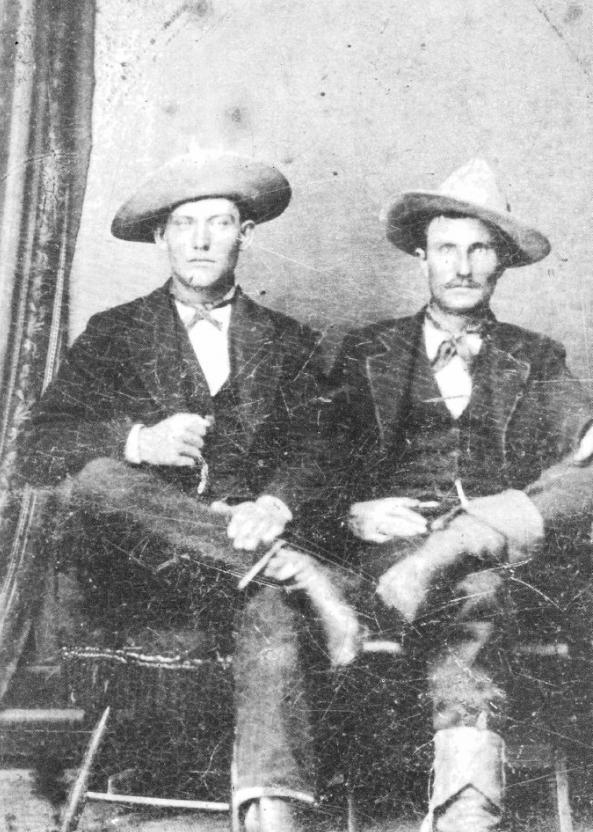

Wes was credited now with at least thirty-nine men. I have mentioned the thirty-one killings of which he ever talked with any detail. There is nothing to show that his notches troubled Wes’ sleep. He felt that every killing was justified—each man he had killed had been attempting to kill him—or at least willing to kill him. It was a bulldog’s existence, that of the frontier, of Texas, in the ’70s. But the charmed life he had led could not preserve its invulnerability forever. The 26th of May, 1874, Wes’ came of age. Twenty-one years old and he had crammed into what is, for most men, merely the beginning of life, the preparation for life, battle, murder, and sudden death. Thirty-nine men…

He went to the races at Comanche that day. The Hardin clan horses took first, second and third. Wes had $3,000 in winnings. He set many a man afoot, then loaned him the horse won on a bet, to ride home again.

Deputy Sheriff Charles Webb, of Brown County, came over to Comanche to capture or kill Wes—or so the news ran—and to kill Wes’ good friend Jim Taylor, for whom a reward was offered. Wes drank steadily. When word came to him that Webb was looking at the sun and remarking that it would go down upon Wes Hardin and Jim Taylor, dead or captured, he laughed.

“Oh, I hope he’ll put it off till dark, or altogether!” he told the men in the saloon.

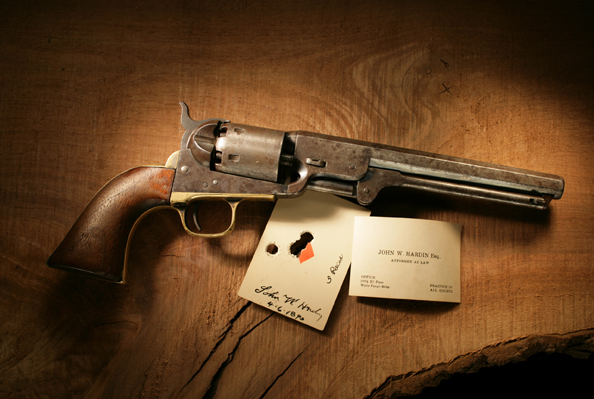

Webb came in. Hardin pushed up to him, looking at the two six-shooters Webb wore. Hardin’s own pistol was out of sight, in the slanting holster sewed to his vest. (His invention, that holster-vest. Jim Gillett wore one in El Paso.) Webb claimed that he had no reason to want John Wesley Hardin. Wes invited him to have a drink and turned slightly away. Bud Dixon, Wes’ cousin, suddenly yelled: “Look out!”

Webb had drawn his six-shooter. He fired and the bullet struck Hardin in the side. Wes jerked out his gun and with the roar of its explosion Charley Webb died, a bullet through his head.

Somewhat later, a mob captured Wes’ brother Joe and his cousins Tom and Bud Dixon, lynched them and went on to shoot two friends of Hardin.

It looked wise to take it on the run. Hardin went to New Orleans, then to Florida. His career in the South was turbulent. He operated saloons in various places. He dealt in cattle and horses and timber. But he was never too busy to gamble and in the natural course of things there were shooting affrays and killings rising out of the young bulldog’s way of living.

Brown Bowen, his wife’s brother, also found Texas too hot for him. There were murder indictments running against Bowen and he found it desirable to slip out of Gonzales County and pay a visit to relatives in Polland, Alabama.

The Rangers were watching Hardin’s relatives, looking for a lead to the wanted gunman. Special Ranger Jack Duncan intercepted a letter addressed to “J. H. Swain, Polland, Alabama” through correspondence Brown Bowen carried on with his father in Gonzales. He and his superior, Lieutenant Armstrong, having conferred with Governor Hubbard in Austin, set out for Polland on Hardin’s trail.

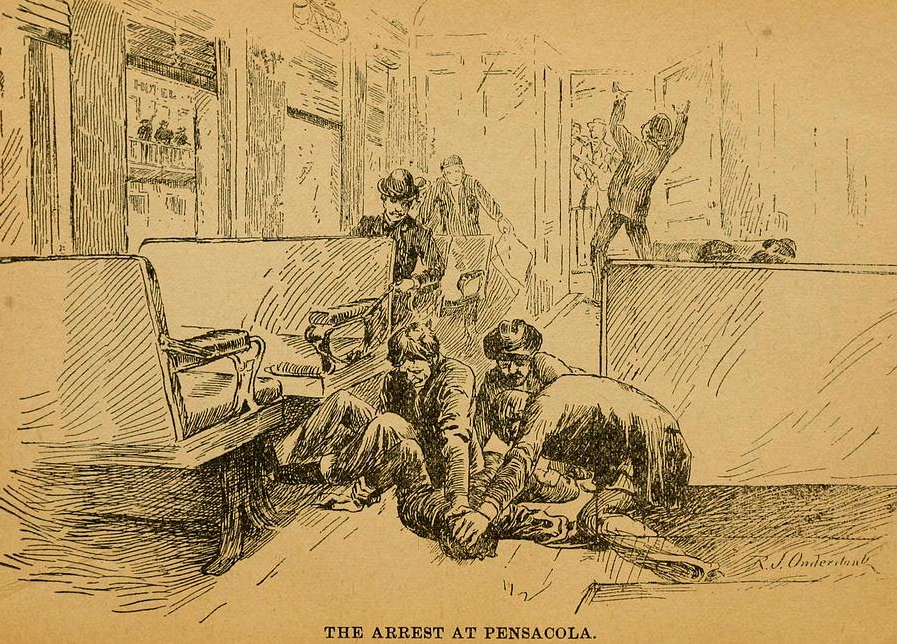

At Pensacola Junction, August 23, 1877, Armstrong and Duncan found Hardin in the smoking car of a train. Several boon companions were with Hardin.

Armstrong had been a sergeant in the company of that famous McNelly who cleaned up the Border country. He was a man fearless to the point of rashness. Duncan was of a different sort, cool, level-headed, calculating. The Rangers had the help of the local sheriff and a posse in making their arrest. Only one of Hardin’s companions showed fight, a boy named Mann, who was shot dead. Hardin was seized before he could draw his pistol. But even with Armstrong’s Colt at his head, he would not surrender. He struggled desperately until overpowered and tied. The posse was all for killing him.

“He’s too brave to kill,” Armstrong told them. “The first man who shoots him—I’ll kill!”

Numerous attempts were made to get Hardin out of the Rangers’ hands, on the trip back to Texas. Some were made by legal authorities enlisted by Mrs. Hardin and her friends. Others were merely gatherings of men resolved to rescue Hardin from Armstrong and Duncan. But the Special Ranger was—in Hardin’s own term— “the wily Jack Duncan.” He foresaw everything; he turned up in court in Mobile in time to quash a habeas corpus hearing; he would not leave the city from the railroad station, but insisted that Hardin be driven out of town several miles to a little siding where the train for Texas might be boarded—and thus avoided collision with Hardin’s friends.

Hardin had now changed his tactics. He played hail-fellow with Armstrong and Duncan. They treated him with the utmost kindness, but not for a moment did Duncan—at least—forget that, with Bill Longley behind the bars, here sat Texas’ most dangerous outlaw, with $4,000 reward on his head.

At Decatur a change of trains was made. The Rangers took Hardin to a hotel room and sent out for meals. Let Hardin tell what happened:

“Jack and Armstrong were now getting intimate with me and when dinner came I suggested the necessity of removing my cuffs and they agreed. Armstrong unlocked the jewelry and started to turn around, exposing his six-shooter to me. Jack jerked him around and pulled his pistol at the same time.

“‘Look out!” he said. ‘John will kill us and escape.’

“Of course I laughed at him and ridiculed the idea. It was really the chance I had been looking for… I intended to jerk Armstrong’s pistol, kill Jack Duncan or make him throw up his hands. I could have made him unlock my shackles, or got the key from his dead body…. That time never came again…”

He must have cursed “wily Jack Duncan” a good many times as the train rolled on toward Texas! He must have thought many a time of those other occasions when the hand of the Law had held him, but had relaxed enough to let him jerk free—thought of the surly, swarthy Smolly, dying on the snowy ridge above the Trinity six years before; of the three State troopers who had gone to sleep in camp and waked only to die…

He had no reason to look ahead with optimism. The factions were at war in Gonzales County. He might well be dragged from jail and lynched as his brother and other relatives had been, at Comanche three years before. If he had to stand trial, it would be in a community bitterly hostile to him.

Nor was he wrong! People flocked to the way stations to see the famous desperado. Some were sympathetic—particularly when they found a handsome young man of pleasant manners and smooth speech—others were hostile, more were merely curious.

Bill Longley—as recorded elsewhere—thought it hard that Hardin should be sentenced to twenty-five years in the penitentiary while he was condemned to death. His complaint seems just. Nobody concerned with Longley’s prosecution has anything to remember with pride. There seems small doubt that Longley was “railroaded” to the gallows without a fair trial.

But Hardin, who complained that he, like Longley, was not permitted to call witnesses because the opposing faction had frightened his witnesses out of the country, was more fortunate in one respect than his rival for gun slinging honors: The State’s own testimony proved that Charley Webb drew his pistol and wounded Hardin before the latter put hand to gun. It could not be charged that Hardin was guilty of murder in the first degree.

But he drew a stiff enough sentence! Twenty-five years in a gun-toting Texas, for killing a man who has already shot you, seems to an unprejudiced observer pretty close to the limit.

While he was held prisoner in Austin jail, his associates were eighty men as desperate, perhaps, as any similar number who could be got together. The Austin Statesman remarks under date of August 29, 1877:

“Some of them are from De Witt and many are considered as desperate characters as Hardin, characterized as ‘the notorious murderer’, though he has not been tried.”

Hardin himself makes much the same remark. He lists as fellow-prisoners Bill Taylor of his own bunch, his brother-in-law, Brown Bowen, John Ringo who was to make six-shooter history in Tombstone and back down the Earps, Manning Clements, John Collins, Jeff Ake, and Pipes and Herndon of the Sam Bass gang.

Certainly, it was a company to make uneasy the jailer! But Lieutenant Reynolds’ Rangers were guarding the neighborhood and he was not an officer whose charges got away.

Hardin was tried for Charley Webb’s killing and, as I have said, suffered the penalties of his turbulent reputation. He was convicted and his enemies were partially satisfied.

He was taken to the penitentiary and it was like his journey from Pensacola Junction—the people thronged to see Wes Hardin. “From the hoary-headed farmer to the little maid hardly in her teens”—all crowded about the wagon where three other prisoners were chained and guarded by a company of Rangers.

He had never before known confinement of more than brief duration. He had been used to good clothing, to boots that fitted. He had been a person of importance in his own community and of notoriety the length and breadth of Texas.

When the prison gates slammed behind him and he was stripped for examination, his hair cropped, his first breakfast of watery coffee, corn bread, fat bacon and molasses put before him, he looked around furiously. It was October 5, 1878. He would be 26 years old the following May. If the State of Texas kept him behind bars for the full sentence prescribed, he would be 50 years old when released—an old man!

He set about his schemes for escape almost at once. But his theory that “in jail even a coward is a brave man” altered with experience to a belief that “convict” and “traitor” were words synonymous. His every plan was reported by stool pigeons. He was beaten unmercifully. He went for long periods to the dungeon. Perhaps he almost envied Brown Bowen, his brother-in law, who was hanged in Cuero for the murder of Thomas Handleman while Hardin lay in Austin Jail.

Months became years. Hardin’s spirit was subdued, if not broken, by confinement and harsh treatment. He gave over attempts to escape, began to study. First it was theology! But soon he decided to take up law.

On February 17, 1894, he was released from Huntsville, and stepped into the open, after more than 15 years of convict-life. Just a month later Governor Jim Hogg granted him full pardon and restoration of citizenship. Prominent men over the state were interested in Hardin. They wrote him friendly letters; they offered him help in establishing himself for a new beginning; they were uniformly cordial and they pointed out to him that, with his intelligence, his courage, he might well be hopeful of the future.

He went home to Gonzales, to his family. He hung out his shingle and began to practice law. But he was too naturally belligerent, too full of strong convictions, ever to keep to the middle of the road. It was a bitter election contest that embroiled him once more in Gonzales politics, factional warfare. He backed one candidate for sheriff and in the course of the struggle bloodshed was very narrowly averted. His man lost and Hardin left Gonzales. He moved to Karnes County.

His wife died shortly after his release. In London, Texas, Hardin married a young girl—hardly more than a child, so the old-timers tell me. He was restless. He lived with his second wife only the briefest time.

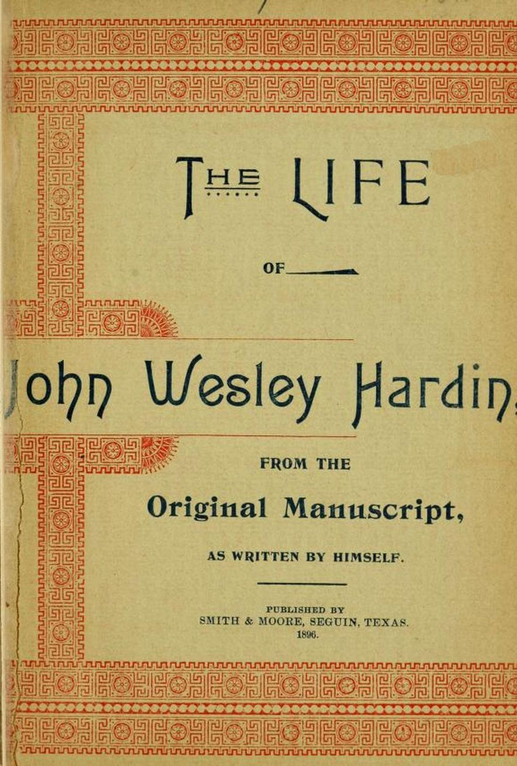

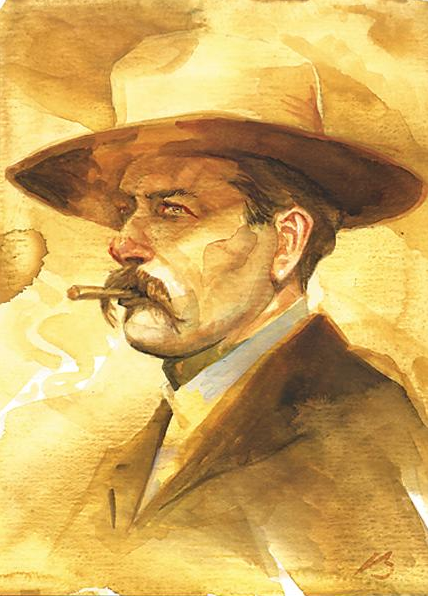

J. Marvin Hunter, historian, editor, who publishes at Bandera a quaint little magazine called The Frontier Times, was setting type in his father’s newspaper office at Mason, in those days. He recalls how a tall, mustached man of middle age came into the office one morning, bearing a thick manuscript. It was a book he wanted published.

“I’m sorry that our press isn’t large enough to handle that sort of work,” Judge Hunter told the stranger. “Whom have I the honor of addressing?”

“John Wesley Hardin,” the other said—with equal courtesy. “This is the story of my life.”

Young Marvin stared open-eyed at the famous gunman who had forty-odd notches on his weapons. He recalls particularly how little Hardin resembled the desperado.

About this time a call came to Hardin, from Pecos City. It was from Jim Miller and, whatever we may think of Miller today, to Hardin it was a clan-call, for Miller was a brother-in-law of Manning Clements and the Hardins and Clementses were cousins.

Jim Miller stands well up at the head of list, among Texas’ cold-eyed killers. His trail across West Texas and New Mexico is a crimson trail. Sometimes he served as a deputy sheriff or deputy marshal. More often he merely rode with quiet tongue across a given scope of range—and his silence would be broken by the sound of his rifle or pistol. Someone would fall dead and there would be the sound of a horse galloping fast away and Jim Miller would report to his paymaster that he had “collected the tail feathers” of such and such a one and—“please send the amount agreed upon.”

In Pecos, he had “tangled ropes” with Bud Frazer, the sheriff. They had a good deal of trouble and finally met on the street and Frazer got into action first. But his shot merely crippled Miller. As the old boys tell it, Frazer upon learning that he had not killed the formidable gunman, left the country in a cloud of dust. He went over to Eddy and ran a livery business. But he had been indicted for assault with intent to kill and the case was transferred to El Paso. Hardin came down to assist in the prosecution.

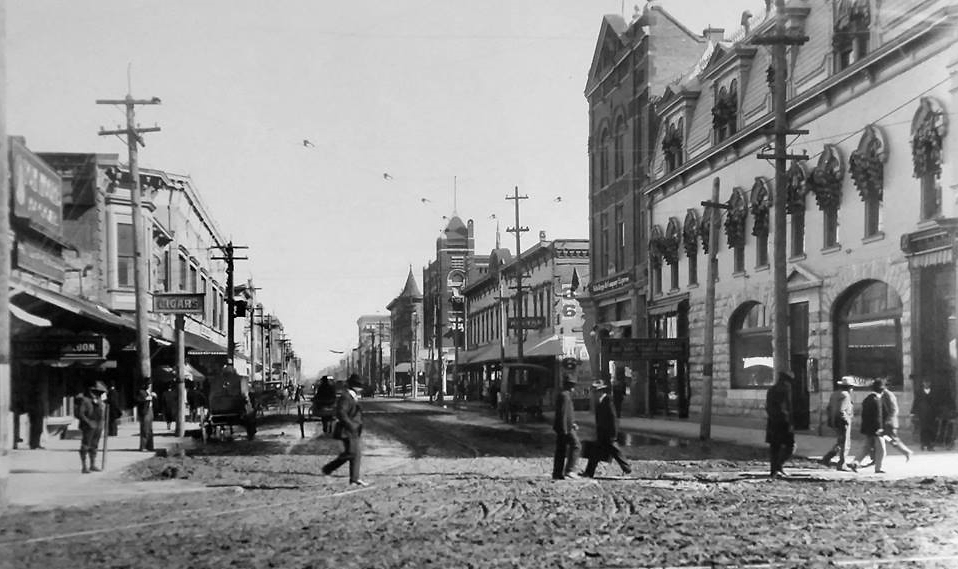

One of the abiding traditions of El Paso has to do with Mayor Johnson’s receipt of the news of Hardin’s coming to town. According to this story, the mayor and a delegation of leading citizens, including Chief of Police Jeff Milton, went down to the train to meet the famous gunman. But not to do him honor. On the contrary, they are said to have warned Hardin that El Paso wanted no desperadoes and his first wild and woolly play would be his last.

Perhaps this occurred. But if so, there is no reflection in the local papers of any such sentiment—none that I can discover, at least—unless a little news-note in the Around Town column, in the Times of April 2, 1895, was directed at John Wesley:

“It is understood that a lot of the people interested in the Frazer-Miller case from Pecos come to El Paso armed to the teeth and they will no doubt be taught the lesson that El Paso has her own peace officers. The day for man killers in this town has passed.”

But Juan Hart, publisher of the Times, no less than “Uncle Jimmy” Smith of the Herald, was a doughty exponent of Personal Journalism and the Times seems to have indirectly championed Bud Frazer in his trouble. At least, under date of March 24, one reads that “Bud Frazer is still very much alive, despite the efforts of the Miller gang at Pecos to exterminate him. He is now in the city from Eddy, where he is conducting a livery business.”

Apparently, John Wesley Hardin did not stand out unfavorably in an El Paso which needed a peace officer like Jeff Milton to preserve order, and which elected a curly wolf like Old John Selman a constable. Indeed, he seems to have produced a very favorable impression, somewhere in the Times office! One has to recall that this was the day of the “Paid Personal.” But, whether he made a call upon the editor and spellbound him, or merely wrote and paid for insertion of the following, the “notice” is nothing if not commendatory:

“Among the leading citizens of Pecos City now in El Paso is John Wesley Hardin, Esq., a leading member of the Pecos City bar. In his younger days Mr. Hardin was as wild as the broad western plains upon which he was raised. But he was a generous, brave-hearted youth, and got into no small amount of trouble for the sake of his friends, and soon gained the reputation for being quick tempered and a dead shot.

“In those days, when one man insulted another, one of the two died then and there. Young Hardin, having a reputation for being a man who never took water, was picked out by every bad man who wanted to make a reputation, and that was where the ‘bad men’ made a mistake, for the young westerner still survives many warm and tragic encounters.

“Forty-one years has steadied the impetuous cowboy down to a quiet, dignified, peaceable man of business. Mr. Hardin is a modest gentleman of pleasant address. But underneath the dignity is a firmness that never yields, except to reason and to law. He is a man who makes friends of all who come in close contact with him.

“He is here as associate attorney for the prosecution in the case of The State vs. Bud Frazer, charged with assault with intent to kill. Mr. Hardin is known all over Texas. He was born and raised in this state.”

Certainly, he could have asked little more in the way of a “write-up!” Not a word about his penitentiary record; nothing but florid recital of his virtues. If he had been running for office as Juan Hart’s candidate, the Times could not have done much more for him!

The jury in the Frazer trial could not agree and Judge Buckler at last discharged them on April 14, 1895. (At a second trial in Colorado City, Frazer was acquitted. Jim Miller later killed Bud in Toyah, Texas, emptying a shotgun into his enemy as Frazer sat at a poker table.)

Hardin looked El Paso over, during those days of the Frazer trial. Apparently, the border suited him. He had already discovered that Texas had not forgotten him. Wherever he went, heads turned and eyes came to him. After fifteen years of repression, small wonder that Hardin began to strut and swell in such an atmosphere.

Even though Mayor Johnson did not warn Hardin to be careful of his conduct in El Paso, any gunfighter with a grain of discretion would have been thoughtful in the Pass City, one thinks!

Jeff Milton, veteran badge wearer, as chief of police rode the town with a firm, if light, hand. Milton is one of the really great old-time officers and as a gun-expert need touch his hat to very, very few!

Old John Selman was of entirely different type. Although he wore the badge at this time, of Constable, Precinct One, and had the backing of prominent citizens, he was of the killer type and there were mysterious blind spots on his backtrail. As a gunman he stood as one of the experts.

Deputy U. S. Marshal George Scarborough, ex-sheriff of Jones County, was another peace officer of the day who did not back water in the face of any sort of gun-competition.

There were other belligerent gentlemen on the stage, men who simply could not understand that anyone might be their superiors at any sort of fighting.

Hardin began the practice of law in El Paso. And out of his very first case came lines that were to tangle his feet and bring about his fall a few months later.

Two cowboys of the period had been “using the sticky loop” in Texas and New Mexico. Vic Queen was a tall, straight, vividly brunette man. His partner, Martin M’Rose, was not so much of a figure, being of middle height and possessed of light brown hair and eyes that did not impress anyone enough to permit memory of their exact color.

The pair were unusual in one respect: They got themselves arrested and so irritated stockmen that, when they jumped bond the Live Stock Protective Association of southeastern New Mexico posted $1,000 reward for the arrest of each, to which their bondsmen added $2.50.

They crossed into Mexico and rode along the safe side of the Rio Grande toward Juarez, El Paso’s neighbor city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Now enters the picture a dashing blonde lady calling herself Mrs. ‘Rose. She followed her consort and Vic Queen and stopped in El Paso. Apparently, she was here before John Wesley Hardin arrived from Pecos.

She had statuesque beauty and she had money. Presently, she was to attract Hardin’s eye. But before this, on March 26, 1895, Jeff Milton had secured the arrest in Juarez of Vic Queen. On April 6, M’Rose was arrested at Magdalena by Beauregard Lee, of Raton, New Mexico. Both men were lodged in the Juarez calaboza and a bitter legal fight began. The New Mexico authorities were trying to extradite the pair. M’Rose and Queen were fighting extradition and attempting to secure their release from jail. In El Paso and Juarez were grim men of two factions, watching each other steadily—friends of the two cow-thieves, and officers from New Mexico who included the redoubtable ex-Texas Ranger captain, George Baylor.

Moving about the town, John Wesley Hardin soon crossed the trail of the blonde lady. And he was retained in the case pending between the New Mexican authorities and the jailed men. Feeling ran higher and became more bitter.

Apparently, Hardin had lost little of either his belligerence or his magic with the Colts. Nor did his weakness for Mrs. M’Rose extend to those whose money was in her custody—$3,000 of it, according to old-time officers who were in position to know. He and his clients had decided to resort to a writ of habeas corpus, in an effort to get M’Rose and Queen back on the Texas side of the Rio Grande. M’Rose’s friends sent Hardin word that if he continued to interfere with the defense plans, he could expect trouble.

The Times of April 23, 1895, carries the following item:

“The toughs who rallied around the imprisoned M’Rose and Queen in Juarez gave it out that they would bulldoze Attorney John Wesley Hardin if he tried professionally to defeat their schemes to defeat extradition. Last night Mr. Hardin met the gang in Juarez and slapped their faces one after another.”

And if Jeff Milton had not been one of Hardin’s companions that evening, one of the men slapped would have died in that saloon backroom where the encounter took place. The arguments pro and con between Hardin and M’Rose’s friends had got to the face-slapping stage. Hardin struck one Fenessy of the other side and, whipping out his pistol, rammed it into Fenessy’s belly. Jeff Milton yelled at him, then argued him out of his intention to kill Fenessy, who had been loudest of the M’Rose faction from the beginning.

It is said that Hardin had lost little of his belligerence or his magic with the Colts… But, studying him in the light of his recorded actions, and the varying testimony of those who knew him well before and after his imprisonment, it seems to me that he was a shell of the young fire-eater who went to Huntsville prison in ’78. I cannot explain him otherwise—the contradictions of his last days.

He drank heavily, drank steadily. He was quarrelsome, given to braggadocio and ferocious glaring. In and around El Paso he swaggered it in the role of The Famous Wes Hardin. He lost at faro – but put hand on six shooter and snarled at the house-men and snatched the money. He scooped in poker-pots without showing his hand, overbearing the other players. But—not always! There were some who refused to be bulldozed by Hardin or anyone else… And herein lies one of the contradictions noted in his conduct! He who had made a joke of the saying that he “took no sass but sassparilla!” did not whip out his lethal Colts when he was crossed.

Jeff Milton denies it, but there are several in El Paso who recall the time when Milton (no longer chief of police) and Hardin had an argument which ended by Milton slapping Hardin’s face—without any return.

And there was “Colonel” Eakins (the title was complimentary, for Eakins was a pioneer real estate man of El Paso)… Eakins was no respecter of persons and when Hardin picked a quarrel with him, Eakins promptly knocked him down and then, to add insult to injury, sat comfortably upon Hardin and was pounding away when old Judge Coldwell rushed up and in a very panic tried to intervene.

“My God!” he cried, to Eakins. “Don’t you know what you are doing? Hardin will kill you for this!”

“So far as I’m concerned,” the doughty Eakins replied, “this is the man who called me a liar!”

M’Rose was dead, now. Hardin had been successful in his campaign to attach Mrs. M’Rose and the M’Rose Queen bankroll. So much so that in his last days, M’Rose in Juarez could not get in touch with the lady. He enlisted Deputy U. S. Marshal George Scarborough and Scarborough tried to persuade the dashing blonde to cross to Juarez and talk to her consort. He returned to M’Rose and reported that the only way M’Rose could talk to Mrs. M’Rose was to come to El Paso.

With $1,250 reward on his head, M’Rose was naturally unwilling to come into the jurisdiction of Texas officers. But thought of the money, or memory of the lady’s charms, got him to mid-river on the Mexican Central trestle one night. Here he stopped. There are conflicting stories concerning what occurred here. I do not profess to know what actually took place, or what circumstances led up to M’Rose’s death. But there were shots and M’Rose was dead.

Jeff Milton, now a Special Ranger, Deputy U. S. Marshal Frank McMahan and Scarborough were indicted for the killing—rather as a technicality, I think— and promptly acquitted.

The result was to make Hardin’s attachment for Mrs. M’Rose almost a regular union. She was addicted to the bottle and the bright lights and given to staging Wild West exhibitions on the street when in her cups. Which brings us to mid-August, 1895…

Hardin was away from town when his mistress created a disturbance and was arrested and fined for carrying a pistol. Young John Selman—so called to distinguish him from his father the constable—was a city policeman and a belligerent soul in his own right. He made the arrest and Hardin was furious when he came back and heard the story.

In my own mind there is no doubt that Selman was perfectly willing to kill Hardin, given opportunity, if not actually “laying for” him. There was much jealousy among the killer-type of gunmen. Each wanted to be cock of the walk. When one killed another, automatically he inherited the dead man’s list of notches.

And the informed had no doubt that someone was going to kill Hardin. He could not strut and brag indefinitely, in such company as El Paso offered. It simply was not on the cards. He would make trouble with some quiet and efficient gentleman and get himself killed, or he would be shot by some glory-hunter.

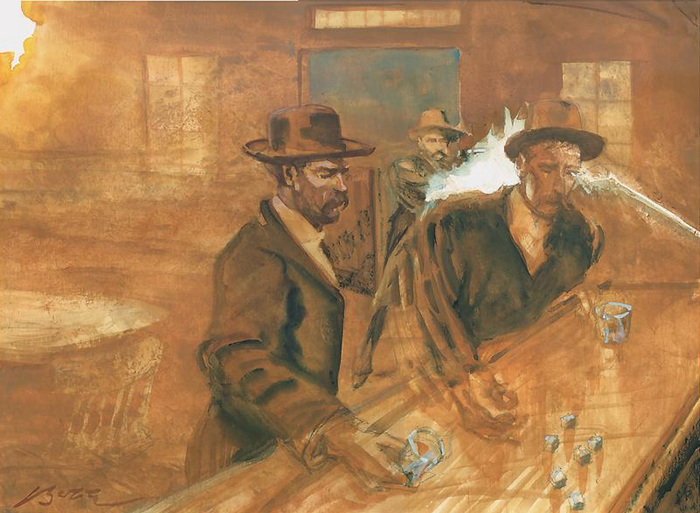

On the evening of August 19, 1895, Hardin encountered Old John Selman near the Acme Saloon of R. B. Stevens, on San Antonio Street. Hardin was reminded of his grievance against Young John, with sight of the constable. By Selman’s testimony, Hardin remarked that Young John was a cowardly This-and-That. They had words and Hardin claimed that he was unarmed.

This assertion is far from convincing. Hardin was always armed. Nor could he have had much hope of making Selman believe the contrary. But, by testimony of Selman, the only witness to the encounter, Hardin went on into the Acme and began shaking dice.

Selman met his son and Captain Carr of the police and told them that he expected trouble—and that the police were to keep out of it, it was a personal matter between Hardin and himself. He sat down on a beer keg outside the Acme. He says that he was seated there when a friend came by and persuaded him to go inside for a drink. But the friend’s testimony conflicts… He says that he found Selman in the saloon and having heard of Hardin’s threats against Selman, warned the constable not to drink! By his testimony, he and Selman walked outside, talking, then returned, he walking ahead of Selman. And he heard shots behind him, as he walked toward the back of the saloon.

He was a cautious man, this grocer-friend of Selman’s. He kept his eyes straight front and walked on out through a cloud of pistol smoke. He saw nothing.

But Hardin, standing at the bar with Henry Brown, fell dead, a bullet through his head, another through his body, a third through the right arm.

Wes’ Hardin, most notorious of Texas’ Six-Shooter Experts, was dead, last of the trio which had summed up Triggernometry in the ’70s, gone at last to join Bill Longley and Ben Thompson.

Selman was tried for the killing and to his counsel insisted that he had not shot Hardin in the back; that Hardin was looking him in the eye and apparently about to draw a pistol when he—Selman—fired.

Ex-Senator A. B. Fall assisted in the defense and he tells me an interesting story in connection with this assertion of Selman’s. He says that he came to town after the killing and agreed to help defend Selman. But he insisted on going over all the case for himself. Examination of Hardin’s hat showed that he had been shot from behind, just as the examining physicians had said— and contrary to Selman’s dogged story.

“I couldn’t help being impressed by Selman’s appearance when he assured me that he had been looking Hardin in the eye,” Fall says. “I knew Selman well and I felt that he wouldn’t lie to me and he had all the appearance of a man telling what he firmly believed. It puzzled me, so I went down to look over the scene of the killing. I stopped at the Acme’s door and looked inside. There was a man standing at the bar and he lifted his head. Then I had the explanation of Selman’s statement. For as that man stared into the mirror, I had the illusion for an instant of looking him straight in the eyes.”

But, be that as it may, Selman was easily acquitted of a charge of murder. Hardin’s reputation, his actions, helped free Selman. John Wesley Hardin was buried in old Concordia Cemetery and the tale of forty-odd notches was told.