Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Types of Naval Officers, Drawn From the History of the British Navy, by A. T. Mahan (published 1902). All spelling in the original.

The first great name in British naval annals belonging distinctively to the eighteenth century rather than to the seventeenth, is that of Edward Hawke. He was born in 1705, of a family of no marked social distinction, his father being a barrister, and his grandfather a London merchant. His mother’s maiden name was Bladen. One of her brothers held an important civil office as Commissioner of Trade and Plantations, and was for many years a member of Parliament. Under the conditions which prevailed then, and for some generations longer, the influence attaching to such positions enabled the holder to advance substantially the professional interests of a naval officer. Promotion in rank, and occupation both in peace and war, were largely a matter of favor. Martin Bladen naturally helped his nephew in this way, a service especially valuable in the earlier part of a career, lifting a man out of a host of competitors and giving him a chance to show what was in him. It may readily be believed that Hawke’s marked professional capacity speedily justified the advantage thus obtained, and he seems to have owed his promotion to post-captain to a superior officer when serving abroad; though it is never possible to affirm that even such apparent official recognition was not due either to an intimation from home, or to the give and take of those who recognized Bismarck’s motto, “Do ut des.”

However this may have been, the service did not suffer by the favors extended to Hawke. Nor was his promotion unduly rapid, to the injury of professional character, as often happened when rank was prematurely reached. It was not till March 20, 1734, that he was “made post,” as the expression went, by Sir Chaloner Ogle into the frigate Flamborough, on the West India Station. Being then twenty-nine years old, in the prime of life for naval efficiency, he had reached the position in which a fair opportunity for all the honors of the profession lay open to him, provided he could secure occupation until he was proved to be indispensable. Here also his uncle’s influence stood good. Although the party with which the experienced politician was identified had gone out of power with Sir Robert Walpole, in 1742, his position on the Board dealing with Colonial affairs left him not without friends. “My colleague, Mr. Cavendish,” he writes, “has already laid in his claim for another ship for you. But after so long a voyage” (he had been away over three years) “I think you should be allowed a little time to spend with your friends on shore. It is some consolation, however, that I have some friends on the new Board of Admiralty.” “There has been a clean sweep,” he says again, “but I hope I may have some friends amongst the new Lords that will upon my account afford you their protection.”

This was in the beginning of 1743, when Hawke had just returned from a protracted cruise on the West India and North American stations, where by far the greater part of his early service was passed. He never again returned there, and very shortly after his uncle’s letter, just quoted, he was appointed to the Berwick, a ship-of-the-line of seventy guns. In command of her he sailed in September, 1743, for the Mediterranean; and a few months after, by his decided and seamanlike course in Mathews’s action, he established his professional reputation and fortunes, the firm foundations of which had been laid during the previous years of arduous but inconspicuous service. Two years later, in 1746, Martin Bladen died, and with him political influence, in the ordinary acceptation, departed from Hawke. Thenceforth professional merit, forced upon men’s recognition, stood him in stead.

He was thirty-nine when he thus first made his mark, in 1744. Prior to this there is not found, in the very scanty records that remain of his career, as in that of all officers of his period while in subordinate positions, any certain proof that he had ever been seriously engaged with an enemy. War against Spain had been declared, October 19, 1739. He had then recently commissioned a fifty-gun ship, the Portland, and in her sailed for the West Indies, where he remained until the autumn of 1742; but the inert manner in which Spain maintained the naval contest, notwithstanding that her transmarine policy was the occasion of the quarrel, and her West Indian possessions obviously endangered, removed all chance of active service on the large scale, except in attacking her colonies; and in none of those enterprises had the Portland been called upon to share.

Meantime, a general European war had begun in 1740, concerning the succession to the Austrian throne; and, in the political combinations which followed, France and Great Britain had as usual ranged themselves on opposite sides, though without declaring war upon each other. Further, there had existed for some time a secret defensive alliance between France and Spain, binding each party to support the other, under certain conditions, with an effective armed force, to be used not for aggressive purposes, but in defence only. It was claimed, indeed, that by so doing the supporting country was not to be considered as going to war, or even as engaged in hostilities, except as regarded the contingent furnished. This view received some countenance from international law, in the stage of development it had then reached; yet it is evident that if a British admiral met a Spanish fleet, of strength fairly matching his own, but found it accompanied by a French division, the commander of which notified him that he had orders to fight if an attack were made, friendly relations between the two nations would be strained near to the breaking point. This had actually occurred to the British Admiral Haddock, in the Mediterranean, in 1741; and conditions essentially similar, but more exasperated, constituted the situation under which Hawke for the first time was brought into an action between two great fleets.

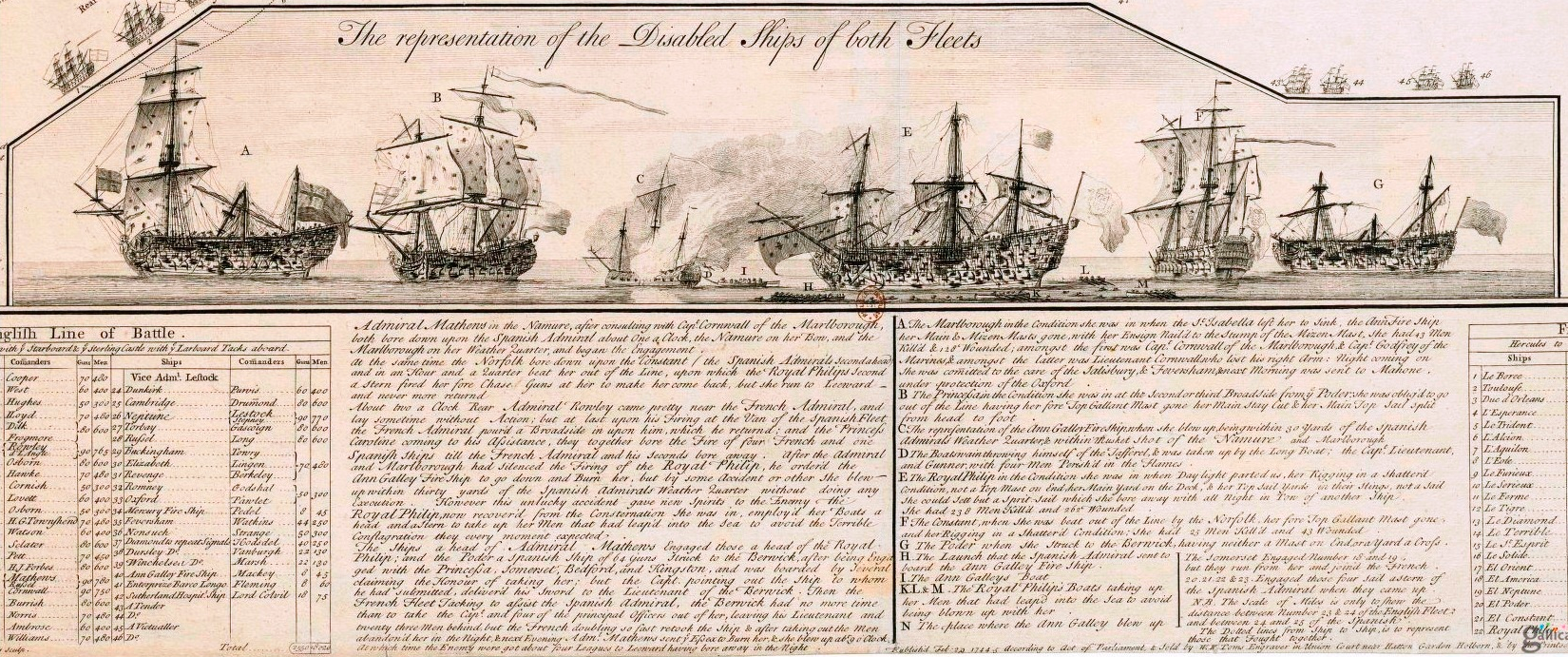

On the 11th of January, 1744, when the Berwick joined the British fleet, it had rendezvoused at the Hyères Islands, a little east of Toulon, watching the movements of twelve Spanish ships-of-the-line, which had taken refuge in the port. As these were unwilling to put to sea trusting to their own strength, the French Admiral De Court was ordered to accompany and protect them when they sailed. This becoming known, Admiral Mathews had concentrated his fleet, which by successive reinforcements—the Berwick among others—numbered twenty-eight of-the-line when the allies, in about equal force, began to come out on the 20th of February.

The action which ensued owes its historical significance wholly to the fact that it illustrated conspicuously, and in more than one detail, the degenerate condition of the official staff of the British navy; the demoralization of ideals, and the low average of professional competency. That there was plenty of good metal was also shown, but the proportion of alloy was dangerously great. That the machinery of the organization was likewise bad, the administrative system culpably negligent as well as inefficient, had been painfully manifested in the equipment of the ships, in the quality of the food, and in the indifferent character of the ships’ crews; but in this respect Hawke had not less to complain of than others, having represented forcibly to the Admiralty the miserable unfitness of the men sent him. Nevertheless, despite all drawbacks, including therein a signalling system so rudimentary and imperfect as to furnish a ready excuse to the unwilling, as well as a recurrent perplexity to those honestly wishing to obey their orders, he showed that good will and high purpose could not only lead a man to do his full duty as directed, but guide him to independent initiative action when opportunity offered. Under all external conditions of difficulty and doubt, or even of cast-iron rule, the principle was as true then as when Nelson formulated it, that no captain when in doubt could do very wrong if he placed his ship alongside an enemy. That Hawke so realized it brought out into more glaring relief the failure of so many of his colleagues on this occasion.

But the lesson would be in great part lost, if there were to be seen in this lapse only the personal element of the delinquents, and not the widespread decline of professional tone. Undoubtedly, of course, it is true that the personal equation, as always, made itself felt, but here as intensifying an evil which had its principal source elsewhere.

Hawke carried Nelson’s maxim into effect. Upon the signal for battle he took his own ship into close action with the antagonist allotted to him by the order of the fleet; but after beating her out of the line he looked round for more work to do. Seeing then that several of the British vessels had not come within point-blank, but, through professional timidity, or over-cautious reverence for the line of battle, were engaging at long range a single Spaniard, he quitted his own position, brought her also to close quarters, and after an obstinate contest, creditable to both parties, forced her to surrender. She was the only ship to haul down her flag that day, and her captain refused to surrender his sword to any but Hawke, whom alone he accepted as his vanquisher.

A generation or two later Hawke’s conduct in this matter would have drawn little attention; it would not have been exceptional in the days of St. Vincent and Nelson, nor even in that of Howe. At the time of its occurrence, it was not only in sharp contrast with much that happened on the same field of battle, but it was somewhat contrary to rule. It possessed so far the merit of originality; and that on the right side,—the side of fighting. As in all active life, so in war a man is more readily pardoned for effecting too much than too little; and it was doubly so here, because it was evident from the behavior of his peers that he must expect no backing in the extra work he took upon himself. Their aloofness emphasized his forwardness; and the fact that through the withdrawal of his admiral for the night, the prize was ultimately retaken, together with an officer and seamen he had placed on board, fixed still further attention upon the incident, in which Hawke’s action was the one wholly creditable feature.

The effect of the battle upon his fortunes was summed up in a phrase. When his first lieutenant was sent to report the loss of the prize-crew to Rear-Admiral Rowley, the commander of the division, the latter replied, among other things, that “he had not been well acquainted with Captain Hawke before, but he should now be well acquainted with him from his behavior.” Like Nelson at St. Vincent, Hawke was now revealed, not to the navy only but to the nation,—”through his behavior.” Somewhat exceptionally, the king personally took knowledge of him, and stood by him. George II. paid most interested attention to the particulars elicited by the Courts-Martial,—a fact which doubtless contributed to make him so sternly unyielding in the case of Byng, twelve years later. To the king Hawke became “my captain;” and his influence was directly used when, in a flag promotion in 1747, some in the Admiralty proposed to include Hawke in the retirement of senior captains, which was a common incident in such cases. “I will not have Hawke ‘yellowed,'” was the royal fiat; a yellow admiral being the current phrase for one set aside from further active employment.

Such were the circumstances under which Hawke first received experience of the fighting conditions of the navy. Whatever his previous attitude towards accepted traditions of professional practice, this no doubt loosened the fetters; for they certainly never constrained him in his subsequent career. He remained in the Mediterranean fleet, generally upon detached services in command of divisions of ships, until the end of 1745. Returning then to England, he saw no further active service until he became a Rear-Admiral—of the White—on July 15, 1747.

The promotions being numerous, Hawke’s seniority as captain carried him well up the list of rear-admirals, and he was immediately employed; hoisting his flag July 22d. He then became second to Sir Peter Warren, commander-in-chief of the “Western Squadron.” This cruised in the Bay of Biscay, from Ushant to Finisterre, to intercept the naval divisions, and the accompanying convoys of merchant and transport ships, with which the French were then seeking to maintain their colonial empire in North America and in India: an empire already sorely shaken, and destined to fall finally in the next great war.

Hawke was now in the road of good luck, pure and unadulterated. His happy action in capturing the Poder illustrates indeed opportunity improved; but it was opportunity of the every day sort, and it is the merit that seized it, rather than the opportunity itself, that strikes the attention. The present case was different. A young rear-admiral had little reason to hope for independent command; but Warren, a well-tried officer, possessing the full confidence of the First Lord, Anson, himself a master in the profession, was in poor health, and for that reason had applied for Hawke to be “joined with him in the command,” apparently because he was the one flag-officer immediately available. He proposed that Hawke should for the present occasion take his place, sail with a few ships named, and with them join the squadron, then at sea in charge of a captain. Anson demurred at first, on the ground of Hawke’s juniority,—he was forty-two,—and Warren, while persisting in his request, shares the doubt; for he writes, “I observe what you say about the ships abroad being under so young an officer. I am, and have been uneasy about it, though I hope he will do well, and it could not then be avoided.” Anson, however, was not fixed in his opposition; for Warren continued, “From your letter I have so little reason to doubt his being put under my command, that I have his instructions all ready; and he is prepared to go at a moment’s notice.” The instructions were issued the following day, August 8th, and on the 9th Hawke sailed. But while there was in this so much of luck, he was again to show that he was not one to let occasion slip. Admiral Farragut is reported to have said, “Every man has one chance.” It depends upon himself whether he is by it made or marred. Burrish and Hawke toed the same line on the morning of February 22d, and they had had that day at least equal opportunity.

Hawke’s adequacy to his present fortune betrayed itself again in a phrase to Warren, “I have nothing so much at heart as the faithful discharge of my duty, and in such manner as will give satisfaction both to the Lords of the Admiralty and yourself. This shall ever be my utmost ambition, and no lucre of profit, or other views, shall induce me to act otherwise.” Not prize-money; but honor, through service. And this in fact not only ruled his thought but in the moment of decision inspired his act. Curiously enough, however, he was here at odds with the spirit of Anson and of Warren. The latter, in asking Hawke’s employment, said the present cruise was less important than the one to succeed it, “for the galleons”—the Spanish treasure-ships—”make it a general rule to come home late in the fall or winter.” Warren by prize-money and an American marriage was the richest commoner in England, and Anson it was that had captured the great galleon five years before, to his own great increase; but it was Hawke who, acknowledging a letter from Warren, as this cruise was drawing to its triumphant close, wrote, “With respect to the galleons, as it is uncertain when they will come home and likewise impossible for me to divide my force in the present necessitous condition of the ships under my command, I must lay aside all thoughts of them during this cruise.” In this unhesitating subordination of pecuniary to military considerations we see again the temper of Nelson, between whom and Hawke there was much community of spirit, especially in their independence of ordinary motives and standards. “Not that I despise money,” wrote Nelson near the end of a career in which he had never known ease of circumstances; “quite the contrary, I wish I had a hundred thousand pounds this moment;” but “I keep the frigates about me, for I know their value in the day of battle, and compared with that day, what signifies any prizes they might take?” Yet he had his legal share in every such prize.

The opening of October 14th, the eighth day after Hawke’s letter to Warren just quoted, brought him the sight of his reward. At seven that morning, the fleet being then some four hundred miles west of La Rochelle in France, a number of sails were seen in the southeast. Chase was given at once, and within an hour it was evident, from the great crowd of vessels, that it was a large convoy outward-bound which could only be enemies. It was in fact a fleet of three hundred French merchantmen, under the protection of eight ships-of-the-line and one of fifty guns, commanded by Commodore L’Etenduère. The force then with Hawke were twelve of-the-line and two of fifty guns. Frigates and lighter vessels of course accompanied both fleets. The average size and armament of the French vessels were considerably greater than those of the British; so that, although the latter had an undoubted superiority, it was far from as great as the relative numbers would indicate. Prominent British officers of that day claimed that a French sixty-gun ship was practically the equal of a British seventy-four. In this there may have been exaggeration; but they had good opportunity for judging, as many French ships were captured.

When L’Etenduère saw that he was in the presence of a superior enemy, he very manfully drew out his ships of war from the mass, and formed them in order of battle, covering the convoy, which he directed to make its escape accompanied by one of the smaller ships-of-the-line with the light cruisers. He contrived also to keep to windward of the approaching British. With so strong a force interposed, Hawke saw that no prize-money was easily to be had, but for that fortune his mind was already prepared. He first ordered his fleet to form order of battle; but finding time was thereby lost he changed the signal to that for a general chase, which freed the faster sailers to use their utmost speed and join action with the enemy, secure of support in due time by their consorts as they successively came up.

Half an hour before noon the leading British reached the French rear, already under short canvas. The admiral then made signal to engage, and the battle began. As the ships under fire reduced sail, the others overtook them, passed by the unengaged side and successively attacked from rear to van. As Hawke himself drew near, Rodney’s ship, the Eagle, having her wheel and much of her rigging shot away, was for the time unmanageable and fell twice on board the flag-ship, the Devonshire, driving her to leeward, and so preventing her from close action with the French flag-ship Tonnant, of eighty guns, a force far exceeding that of the Devonshire, which had but sixty-six. “This prevented our attacking Le Monarque, 74, and the Tonnant, within any distance to do execution. However we attempted both, especially the latter. While we were engaged with her, the breechings of all our lower-deck guns broke, and the guns flew fore and aft, which obliged us to shoot ahead, for our upper guns could not reach her.” The breaking of the breechings—the heavy ropes which take the strain of the guns’ recoil—was doubtless accelerated by the undue elevation necessitated by the extreme range. The collision with the Eagle was one of the incidents common to battle, but it doubtless marred the completeness of the victory. Of the eight French ships engaged, six were taken; two, the Tonnant and her next astern, escaped, though the former was badly mauled.

Despite the hindrance mentioned, Hawke’s personal share in the affair was considerable, through the conspicuous activity of the flag-ship. Besides the skirmish at random shot with the Tonnant, she engaged successively the Trident, 64, and the Terrible, 74, both which were among the prizes. He was entirely satisfied also with the conduct of all his captains,—save one. The freedom of action permitted to them by the general chase, with the inspiring example of the admiral himself, was nobly used. “Captain Harland of the Tilbury, 60, observing that the Tonnant fired single guns at us in order to dismast us, stood on the other tack, between her and the Devonshire, and gave her a very smart fire.” It was no small gallantry for a 60 thus to pass close under the undiverted broadside of an 80,—nearly double her force,—and that without orders; and Hawke recognized the fact by this particular notice in the despatch. With similar initiative, as the Tonnant and Intrépide were seen to be escaping, Captain Saunders of the Yarmouth, 64, pursued them on his own motion, and was accompanied, at his suggestion, by the sixty-gun ships of Rodney and of Saumarez. A detached action of an hour followed, in which Saumarez fell. The enemy escaped, it is true; but that does not impeach the judgment, nor lessen the merits, of the officers concerned, for their ships were both much smaller and more injured than those they attacked. Harland and Saunders became distinguished admirals; of Rodney it is needless to say the same.

In his report of the business, Hawke used a quaint but very expressive phrase, “As the enemy’s ships were large, they took a great deal of drubbing, and (consequently) lost all their masts, except two, who had their foremasts left. This has obliged me to lay-to for these two days past, in order to put them into condition to be brought into port, as well as our own, which have suffered greatly.” Ships large in tonnage were necessarily also ships large in scantling, heavy ribbed, thick-planked, in order to bear their artillery; hence also with sides not easy to be pierced by the weak ordnance of that time. They were in a degree armored ships, though from a cause differing from that of to-day; hence much “drubbing” was needed, and the prolongation of the drubbing entailed increase of incidental injury to spars and rigging, both their own and those of the enemy. Nor was the armor idea, directly, at all unrecognized even then; for we are told of the Real Felipe in Mathews’s action, that, being so weakly built that she could carry only twenty-four-pounders on her lower deck, she had been “fortified in the most extraordinary surprising manner; her sides being lined four or five foot thick everywhere with junk or old cables to hinder the shot from piercing.”

It has been said that the conduct of one captain fell under Hawke’s displeasure. At a Council of War called by him after the battle, to establish the fitness of the fleet to pursue the convoy, the other captains objected to sitting with Captain Fox of the Kent, until he had cleared himself from the imputation of misbehavior in incidents they had noticed. Hawke was himself dissatisfied with Fox’s failure to obey a signal, and concurred in the objection. On the subsequent trial, the Court expressly cleared the accused of cowardice, but found him guilty of certain errors of judgment, and specifically of leaving the Tonnant while the signal for close action was flying. As the Tonnant escaped, the implication of accountability for that result naturally follows. For so serious a consequence the sentence only was that he be dismissed his ship, and, although never again employed, he was retired two years after as a rear-admiral. It was becoming increasingly evident that error of judgment is an elastic phrase which can be made to cover all degrees of faulty action, from the mistakes to which every man is liable and the most faithful cannot always escape, to conduct wholly incompatible with professional efficiency or even manly honor.

The case of Fox was one of many occurring at about this period, which, however differing in detail between themselves, showed that throughout the navy, both in active service before the enemy, and in the more deliberate criteria of opinion which influence Courts-Martial, there was a pronounced tendency to lowness of standard in measuring officer-like conduct and official responsibility for personal action; a misplaced leniency, which regarded failure to do the utmost with indulgence, if without approval. In the stringent and awful emergencies of war too much is at stake for such easy tolerance. Error of judgment is one thing; error of conduct is something very different, and with a difference usually recognizable. To style errors of conduct “errors of judgment” denies, practically, that there are standards of action external to the individual, and condones official misbehavior on the ground of personal incompetency. Military standards rest on demonstrable facts of experience, and should find their sanction in clear professional opinion. So known, and so upheld, the unfortunate man who falls below them, in a rank where failure may work serious harm, has only himself to blame; for it is his business to reckon his own capacity before he accepts the dignity and honors of a position in which the interests of the nation are intrusted to his charge.

An uneasy consciousness of these truths, forced upon the Navy and the Government by widespread shortcomings in many quarters—of which Mathews’s battle was only the most conspicuous instance—resulted in a very serious modification of the Articles of War, after the peace. Up to 1748 the articles dealing with misconduct before the enemy, which had been in force since the first half of the reign of Charles II., assigned upon conviction the punishment of “death, or other punishment, as the circumstances of the offence shall deserve and the Court-Martial shall judge fit.” After the experiences of this war, the last clause was omitted. Discretion was taken away. Men were dissatisfied, whether justly or not, with the use of their discretion made by Courts-Martial, and deprived them of it. In the United States Navy, similarly, at the beginning of the Civil War, the Government was in constant struggle with Courts-Martial to impose sentences of severity adequate to the offence; leaving the question of remission, or of indulgence, to the executive. These facts are worthy of notice, for there is a facile popular impression that Courts-Martial err on the side of stringency. The writer, from a large experience of naval Courts, upon offenders of many ranks, is able to affirm that it is not so. Marryat, in his day, midway between the two periods here specified, makes the same statement, in “Peter Simple.” “There is an evident inclination towards the prisoner; every allowance and every favor granted him, and no legal quibbles attended to.” It may be added that the inconvenience and expense of assembling Courts make the executive chary of this resort, which is rarely used except when the case against an accused is pretty clear,—a fact that easily gives rise to a not uncommon assertion, that Courts-Martial are organized to convict.

This is the antecedent history of Byng’s trial and execution. There had been many examples of weak and inefficient action—of distinct errors of conduct—such as Byng was destined to illustrate in the highest rank and upon a large scale, entailing an unusual and conspicuous national disaster; and the offenders had escaped, with consequences to themselves more or less serious, but without any assurance to the nation that the punishment inflicted was raising professional standards, and so giving reasonable certainty that the like derelictions would not recur. Hence it came to pass, in 1749, not amid the agitations of war and defeats, but in profound peace, that the article was framed under which Byng suffered:

“Every person in the fleet, who through cowardice, negligence, or disaffection, shall in time of action, … not do his utmost to take or destroy every ship which it shall be his duty to engage; and to assist all and every of His Majesty’s ships, or those of His allies, which it shall be his duty to assist and relieve, … being convicted thereof by sentence of a Court-Martial, shall suffer death.”

Let it therefore be observed, as historically certain, that the execution of Byng in 1757 is directly traceable to the war of 1739-1747. It was not determined, as is perhaps generally imagined, by an obsolete statute revived for the purpose of a judicial murder; but by a recent Act, occasioned, if not justified, by circumstances of marked national humiliation and injury. The offences specified are those of which repeated instances had been recently given; and negligence is ranked with more positive faults, because in practice equally harmful and equally culpable. Every man in active life, whatever his business, knows this to be so.

At the time his battle with L’Etenduère was fought, Hawke was actually a commander-in-chief; for Warren, through his disorder increasing upon him, had resigned the command, and Hawke had been notified of the fact. Hence there did not obtain in his case the consideration, so absurdly advanced for limiting Nelson’s reward after the Nile, that he was acting under the orders of a superior several hundred miles away. Nevertheless, Hawke, like Nelson later, was then a new man,—”a young officer;” and the honor he received, though certainly adequate for a victory over a force somewhat inferior, was not adequate when measured by that given to Anson, the First Lord of the Admiralty, for a much less notable achievement six months before. Anson was raised to the peerage; Hawke was only given the Order of the Bath, the ribbon which Nelson coveted, because a public token, visible to all, that the wearer had done distinguished service. It was at that period a much greater distinction than it afterwards became, through the great extension in numbers and the division into classes. He was henceforth Sir Edward Hawke; and shortly after the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, signed April 30, 1748, another flag-promotion raised him to the rank of Vice-Admiral, of the Blue Squadron.

Such rank, accompanied by such recognized merit, insured that he should thenceforth always command in chief; and so it was, with a single brief interval due to a very special and exceptional cause to be hereafter related. During the years of peace, from 1748 to 1755, his employment was mainly on shore, in dockyard command, which carried with it incidentally a good deal of presiding over Courts-Martial. This duty, in his hands, could hardly fail to raise professional standards, with all the effect that precedents, established by the rulings and decisions of Courts, civil and military, exert upon practice. Such a period, however, affords but little for narration, either professional or personal, except when the particular occupations mentioned are the subject of special study. General interest they cannot be said to possess.

But while thus unmarked on the biographical side, historically these years were pregnant with momentous events, which not only affected the future of great nations then existing, but were to determine for all time the extension or restriction of their social systems and political tendencies in vast distant regions yet unoccupied by civilized man, or still in unstable political tenure. The balance of world power, in short, was in question, and that not merely as every occurrence, large or small, contributes its something to a general result, but on a grand and decisive scale. The phrase “world politics,” if not yet invented, characterizes the issues then eminently at stake, though they probably were not recognized by contemporaries, still blinded by the traditions which saw in Europe alone the centre of political interests.

To realize the conditions, and their bearing upon a future which has become our present, we should recall that in 1748 the British Empire, as we understand the term, did not exist; that Canada and Louisiana—meaning by the latter the whole undefined region west of the Mississippi—were politically and socially French; that between them the wide territory from the Alleghanies to the Mississippi was claimed by France, and the claim vigorously contested not only by Great Britain herself, but by the thirteen British colonies which became the United States of America; that in India the representatives of both mother countries were striving for mastery, not merely through influence in the councils of native rulers, but by actual territorial sway, and that the chances seemed on the whole to favor France.