Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Makers and Romance of Alabama History, by B. F. Riley (published 1914).

No man in the early annals of the state had a more varied or romantic career than the Rev. Isaac Smith, a courageous missionary of the Methodist Church. His life and labors do not find recognition on the page of secular history, but the contribution which he made to the state in its early formation wins for him a meritorious place in the state’s chronicles. It is doubtful that his name and labors are familiar to the present generation of the great body of Christians of which he was an early ornament, but they are none the less worthy of becoming record.

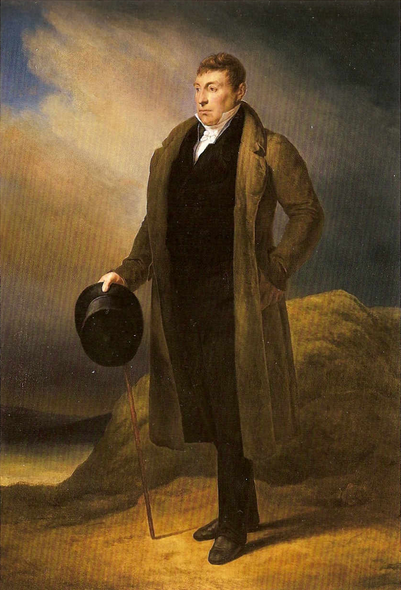

Mr. Smith enlisted from Virginia in the army of Washington while yet a youth. Bright and alert, he was chosen an orderly by Washington, and served in that capacity under both Washington and LaFayette. When the new nation started on its independent career and when the region toward the west began to be opened, Mr. Smith migrated toward the south, became a minister of the Methodist Church, and offered his services as a missionary to the Indian tribes. Hated because of their ferocity, the prevailing idea in the initial years of the nineteenth century was that of the destruction of the red man, but Mr. Smith felt impelled to take to him the gospel of salvation.

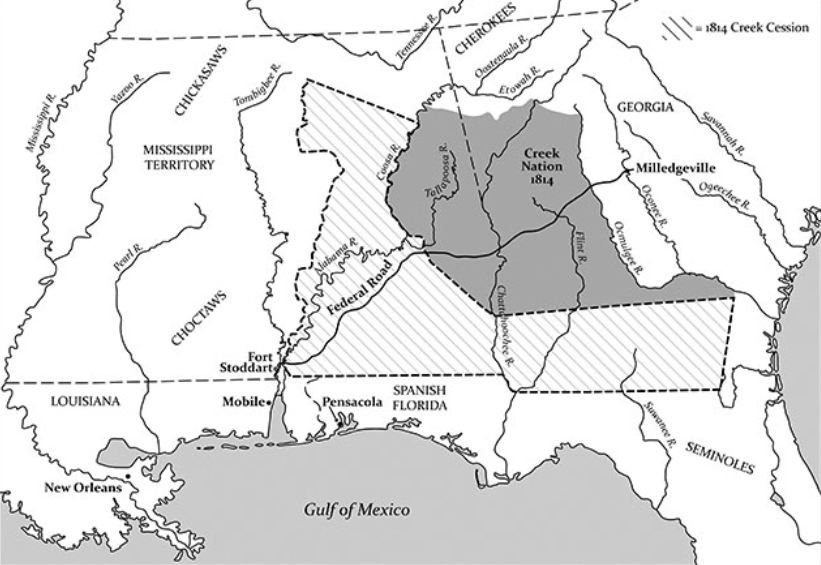

His labors were not confined to any particular region and he trudged the country over, imperiling his life among the wild tribes, who came to love him because he was one pale face who sought to do them good. He founded an Indian school near the Chattahoochee and taught the Indians the elements of the English language. When Bishop Asbury, the most indomitable of all the Methodist bishops, came to the South, Mr. Smith was his close friend and adviser, and most valuable were his services to the bishop in planting Methodism in the lower South.

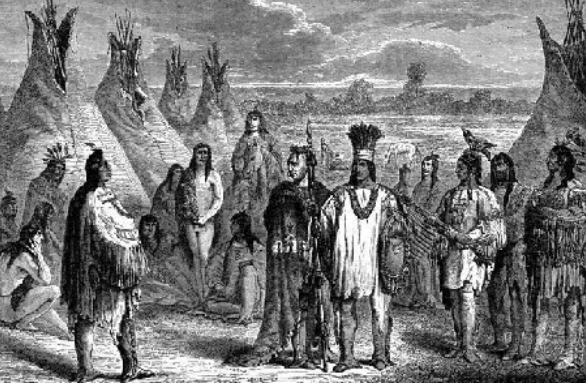

All real teachers are greater learners than instructors, for in their zeal to impart they must first come to acquire. Mr. Smith was an assiduous student and with the growth of his years was an accumulated stock of both wisdom and learning. As he passed the meridian of life he became a power in his denomination and his counsel was freely sought in the high circles of his church. When, in 1825, General LaFayette visited Alabama in his tour of the South, he passed through the Creek Nation, in Georgia, and was escorted by a body of Georgians to the Chattahoochee River and consigned to the care of fifty painted Indian warriors, who vied with the pale faces in doing honor to the distinguished visitor. Rowing LaFayette across the river to the Alabama side, he was met by Rev. Isaac Smith. The great Frenchman instantly recognized Mr. Smith as one of his boy orderlies during the campaigns in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. There was a cordial demonstration of mutual affection between the old French veteran and the younger man, now a Methodist preacher. The painted Indian warriors looked on the exchange of greeting with evident pleasure. It so happened that LaFayette reached the Alabama side just at the point where stood the humble school building of the intrepid missionary.

The first demonstration of greeting being over, Mr. Smith eschewing all conventionality, and, in keeping alike with his Methodist zeal and the joy which he experienced in meeting his old commander, proposed that all bow in prayer. When LaFayette and Smith dropped on their knees the Indian warriors did the same, and there on the banks of the deep rolling Chattahoochee, beneath ancient oaks, in fervid and loud demonstrations of prayer, the voice of Mr. Smith rang out through the deep forests. The picture thus presented was worthy the pencil of the master—the ardent but devout preacher, the great French patriot and the half hundred warriors, each with his hands over his face, praying in the wild woods of Alabama. The prayer was an unrestrained outburst of joy at the meeting of the old commander and a devout invocation for the preservation of the life of the friend of American liberty.

Yielding to the hospitable pressure of the boy soldier of other and stormier days, LaFayette was taken to the humble cottage of the missionary in the woods, and in order partly to entertain the distinguished guest and partly to afford him an insight into aboriginal life, Mr. Smith arranged for a game of ball to be played by the Indians. The day over and LaFayette was taken into the cabin, served with the scanty fare of the pioneer missionary, and beside the primitive fireplace the two, the missionary and the great Frenchman, sat that night and fought over the battles in which both were participants during the Revolution. They parted on the following morning, LaFayette continuing his course toward Cahaba, the state capital, and Mr. Smith resuming his treadmill round of duty as a secluded missionary to the Indians. They parted with the same demonstrations of affection with which they had met, and never again met each other in the flesh.

With cheerful alacrity Mr. Smith continued his work among the Indians, to which work he gave expansion in later years as the white population continued to multiply. He was of immense service to the government in adjusting the claims of the Indians and in pacifying them in the acceptance of the inevitable lot finally meted out to them. As a mediatorial agent Mr. Smith prevented much butchery in those early days when the extinction of the Indian was so seriously desired.

With fame unsought and undesired, the Rev. Isaac Smith continued his missionary and evangelistic labors in Alabama till forced by the weight of years and the results of the privations of pioneer life to retire from the scene of activity. He lived, however, to see the state of his adoption pass from an infantile stage to one of great population and prosperity and to witness the consummation of much of that of which he was one of the original prospectors. Retiring in his last years to Monroe County, Georgia, he died at the age of seventy-six. On the moral and spiritual side he was one of the foundation builders of the state of Alabama. His labor and sacrifice deserve recognition alongside that given of men whose stations in life gave them great conspicuousness in the public eye. He was of the class of men who labored in comparative obscurity, passed away, and in due time are forgotten, but their works do follow them in their everlasting results.

1