Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The French Retreat from Moscow and Other Historical Essays, by Earl Stanhope (published 1876). Reprinted from Fraser’s Magazine of July, 1866.

Legends and mythical stories of various kinds have often in the progress of time gathered around the memories of remarkable men. But there is one curious fact respecting them, which has only of late years been, I might, perhaps, say discovered, certainly, at least, acknowledged. They were formerly thought to have proceeded, like any other falsehoods, from a deliberate purpose to deceive. Now, on the contrary, it seems to be admitted by most persons that they spring up almost unconsciously, and in many cases with a full conviction of their truth by those who first composed them.

The explanation of this the later, and, as I should say, the sounder, view is to be found in the following train of thought which we may assume to have passed in the mind of the credulous fabulist. The thing must have been so and so; therefore the thing was so and so. Such a man was a great hero—of course then he was eight feet high. Such a man was very learned—of course then he had studied the Black Art. Such a man was a Saint—of course then we cannot be wrong in ascribing to him any virtue or any marvel. A process of reasoning like this in the darker ages has sufficed to transform Attila into a giant, Virgil into a magician, and Mahomet into what he certainly never claimed to be, a worker of miracles. Thus does wonder crowd on wonder, each succeeding writer adding a new circumstance, until at last the true historical personage is obscured, and well-nigh lost to sight in a cloud of legendary lore.

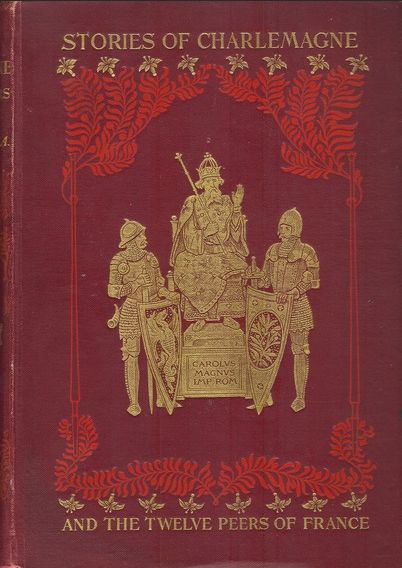

On no period of history however have these legends settled more closely or in greater numbers than on the era of Charlemagne. That great Sovereign might well make a powerful impression on the popular mind. His dominion was as extensive as that of Napoleon, and indeed almost conterminous with it, while the duration of his reign was about three-fold. The excellence of his civil institutions enhanced the glory of his military exploits; and he looms high above the series both of his predecessors and of his descendants.

The life and character of Charlemagne have been described with full authority by Eginhard, an accomplished man of letters, who knew him well, and who filled an office at his Court. This is in truth the only quite accurate and trustworthy record. But on the other hand, it is rather brief and summary, and might well appear to the next age incommensurate to the extent of his conquests and the lustre of his reign. In order to supply this popular craving there came forth in the eleventh century a fabulous history of Charlemagne, falsely ascribed to Turpin, who in the days of the great Emperor had been Archbishop of Rheims. To the same effect, but in divers forms, and in every variety of language, has started up a whole host of ballads and romances.

Eginhard—who by the way was not in truth Eginhard at all, for he always called himself and his contemporaries always called him Einhard or Einhardus—tells us that Charlemagne gave orders to put in writing “the barbaric and most ancient poems in which the deeds and wars of the old Kings were sung.” The object of the great Emperor was that these poems might be safely transmitted to posterity; and the encouragement which he thus afforded to such compositions was, though unconsciously, conducive to his own renown. Other poems in celebration of himself sprung up within the next two centuries; and although the great fame of Charlemagne might fairly rest on his authentic and admitted deeds; yet certainly, in the eyes of our forefathers, and perhaps even in our own, his figure has seemed enormously enhanced and magnified when contemplated through the haze of fiction.

On no point I think has that fiction been so rife as on the many legends relating to the twelve peers of Charlemagne, or, as they are sometimes called, his Paladins. But Charlemagne in real fact had no peers at all. The idea is quite imaginary. It appears to take its rise from the supposition that every man of might ought to be attended by certain followers of commensurate renown; and the gospel history may perhaps have suggested the number twelve as especially solemn and sacred. Thus, in like manner, the Spaniards have an epic on Alexander the Great which dates from the thirteenth century, and which represents the Macedonian conqueror also as having around him his twelve peers.

As to the name of Paladin it has been, like so many others, elucidated by the skill and learning of Ducange. He shows from quotations that the d in the word is a later corruption of t, and that the original term was “Palatin,” not “Paladin;” the signification being “one that belongs to the palace;” a chosen champion, or, if you prefer it, a guardsman of the Sovereign.

Charlemagne himself in some legends is raised to the stature of a giant. His life by the pseudo-Turpin declares that he was at least eight feet high. In other legends he is exalted to the dignity of a Saint. Such at all events was the idea entertained of him by Joan of Arc. She said to Charles VII, at Chinon: —“I tell you, gentle Dauphin, that God has pity on you, your realm, and your people, for St. Louis and St. Charlemagne are on their knees before Him, and offer supplications for you.”

But the event of this reign in which all the poetry, all the legends, all the pseudo-histories, may be said to culminate is the retreat of the French from Spain, attended by the rout of Roncesvalles and the fall of Roland. The real facts are to be gathered from two passages of Eginhard; the one in his “Life of Charlemagne,” and the other in his “Annals” under the date 778. It appears then that Charlemagne being invited to Spain by Ibn Araby, one of his Moorish allies, marched over the Pyrenees, took Pamplona, and advanced to the Ebro, under the walls of Saragoza. There he received hostages in token of submission from several of the Saracen princes, and so far had been successful in his object. But on his march homewards his rearguard was assailed and put to the sword in one of the Pyrenean passes by an armed body of Spanish Basques. “In which conflict,” adds Eginhard, “there fell, with very many others, Anselm, Count of the Palace, and Roland, Præfect of the Marches of Brittany.” I may remark that the name of Roland is here given in the truly barbaric form of Hruodlandus. Much more important is the note here appended by M. Teulet, the latest and best editor of Eginhard. “This passage,” he says, “is the only one among the early historians in which any mention is made of the famous Roland who plays so great a part in all the Carlovingian romances.”

On this scanty groundwork then has arisen, as I may term it, an air-built and fantastic castle. In the first place Roland is made the nephew of Charlemagne—a relationship which would certainly not be unnoticed by Eginhard if it had been real. Next he is invested with the trusty sword Durandal, with which he not only demolishes his enemies, but on one occasion, when pursuing the Moslem, cleaves a pass through the Pyrenees which towers above le Cirque de Gavarni, and is still called la brèche de Roland. Moreover he had a horn scarcely less tremendous, which he sounded in the rout of Roncesvalles to apprise Charlemagne of his danger, and which was heard by the Emperor at a wonderful distance. Further still the romancers are so obliging as to provide him with a bride, the Lady Alda, who remains at Paris, and is awaiting his return from Spain.

As it appears to me, there is here a striking similarity between the Roland of France and the William Wallace of Scotland. The exploits of both are unrecorded in the meagre chronicles of the time. These exploits live only in tradition and in song. But taken as a whole they have, in my judgment, a just claim to be believed. All that tradition has done is to confound the dates and exaggerate the circumstances. We may be sure that so great and so general a fame could not in either case have arisen had not the living hero impressed his image on the public mind. I should therefore entirely agree with Sismondi, who in the second volume of the “History of France” contends, that although Roland may not have been pre-eminent at Roncesvalles, he must have performed achievements and acquired renown in former years, when warring against the Saracens of Spain.

Many other characters of Roncesvalles, though familiar to the minstrel, are wholly unknown to the historian. Such are Oliver and other Paladins in the French romances. Such are Durandarte and Calaynos in the Spanish ballads. But above all in frequency of mention stands Ganelon, the arch-traitor, who misled Roland in the mountain passes and caused the “dolorous rout.” M. Génin, a high authority on the Carlovingian period, has discussed the subject of this name, conceiving it to be derived from an Archbishop of Sens, also called Ganelon, who in 859 was guilty of gross ingratitude to his Sovereign and benefactor Charles the Bald. This seems to me a wholly unfounded idea. The ingratitude of Archbishop Ganelon did not lead to any such striking or fatal action as would at all impress itself on the popular imagination; and moreover it appears that the Emperor and the prelate were reconciled together before the close of the same year. Nor is the sacerdotal character preserved in the legendary Ganelon, as one would expect it to be if an Archbishop had been in truth its prototype.

I consider it therefore very far more probable that Ganelon may have been the real appellation of the treacherous chief of the Navarrese or Spanish Basques who assailed the rear-guard of Charlemagne. Nor does it seems to me at all surprising that Eginhard in his very summary account of the transaction, and omitting even the name of Roncesvalles, should omit also the name of any leader on the enemy’s side.

Be this as it may, however, there is no doubt that within two centuries and a half from the death of Charlemagne the songs and ballads founded on the tragical tale of Roncesvalles had grown popular in France. One proof of this—connected also with the history of England—is given by Robert Wace in his “Roman de Rou.” He tells us that as the Normans of William the Conqueror marched onwards to the battle of Hastings they had in their front ranks a valiant minstrel who from his deeds of arms was surnamed Taillefer, “the hewer of iron.” Taillefer then in the front ranks went singing, as the old French rhymes declare it—

“De Carlemaigne et de Rolant,

Et d’Olivier et des vassaus,

Qui morurent en Rainscevaux.”

Or,

“Of Charlemagne and of Roland,

And of Oliver and the vassals,

Who died in Roncevaux.”

Nor were the ballads of Roncevaux less in vogue among the Spaniards. Of this I may give a striking example, though of a later period, derived from the very masterpiece of Spanish genius.

There is a passage in the second part of “Don Quixote,” where the knight of La Mancha and his squire repair to Toboso in quest of the peerless Dulcinea. There—

“a country labourer passed them going out before daybreak to plough, and as he came along he was singing the old ballad which says—

‘Ill ye fared, ye Frenchmen,

In the chace of Ronceval.’

“‘Let me die,’ said Don Quixote, hearing the ballad, ‘if we have any good success tonight; dost thou hear what the peasant sings, Sancho?’ ”

The ballad thus quoted by Cervantes as sung by a clown in La Mancha, is given by him (so far as regards the opening lines), with some slight verbal differences from its printed form in the “Romancero”—differences which, arising, as of course, from traditionary recitation, are of no particular account. It has been rendered into English verses by Mr. Lockhart, under the title of “The Admiral Guarinos.” And here I cannot but pause for a moment to commemorate the admirable spirit and brilliancy with which Mr. Lockhart has translated—or rather in many cases not exactly translated but rather paraphrased and new-formed—these ancient Spanish ballads. My own warmth of feeling may indeed mislead me when I mention a friend of great intimacy and of cherished memory, now passed away. But I would desire you to consider how strong on this point is the testimony of an American gentleman, Mr. Ticknor. In his excellent book—“The History of Spanish Literature”—Mr. Ticknor observes of these translations of Lockhart, that in his judgment they form “a work of genius beyond any of the sort known to me in any language.”

If indeed I may be permitted to adduce a single instance in proof of this great superiority I shall be content with one, the concluding stanza of this very ballad on the Admiral Guarinos. It relates how Guarinos—not a Moslem as you might imagine from his title, but one of Charlemagne’s captains, and made a prisoner at Roncesvalles—after seven years’ durance being by a fortunate accident mounted once more on his favourite war-horse, and grasping once more his ancient lance, makes his way from Spain. I will give you first a translation as literal as I can make it of the Spanish lines, and next Mr. Lockhart’s version.

Here is a literal translation of the concluding Spanish lines:

“The Moors who looked upon this

All with one accord sought to slay him;

But Guarinos, as became a brave man,

Began forthwith to fight

With the Moors, who were so many

That they might have darkened the sun.

In such guise then did he fight

That he was able to set himself free,

And to reach once again his own land,

His native soil of France.

Great honour there they showed him,

When they thus saw him return.”

How incomparably finer, how far more abounding in life and fire, is the corresponding stanza of Mr. Lockhart:

“With that Guarinos, lance in rest, against the scoffer rode,

Pierced at one thrust his envious breast, and down his turban trode.

Now ride, now ride, Guarinos, nor lance nor rowel spare,

Slay, slay, and gallop for thy life, the land of France lies there!”

But let me make myself clearly understood. While I think that the Spanish lines which close “The Admiral Guarinos” are extremely poor and tame, I am far indeed from applying that character in general to the Spanish ballads, or other lyric pieces. On the contrary, many amongst them possess a natural charm, an inborn simplicity and grace, and sometimes also an exquisite tenderness which cannot be too highly praised, and which seem almost to defy the power of translation. As combining all these qualities I might mention, for instance, the little poem beginning “En los tiempos que me vi,” which is the original of Lockhart’s “Valladolid,” and one other, “La niña Morena,” which is the original of “Zara’s Ear-rings.” In some of these cases, however, the Spanish poem is marred by later interpolations, as Depping considers them, or, as I should rather say, by an original defect in the couleur locale, as the French term it. Thus, in “Zara’s Ear-rings,” the Moorish maiden speaks of herself attending mass, a rite of course, peculiar to the Christians; and also of admiring the rich brocade of a marquis, a title never known among her countrymen.

Excellent as are undoubtedly these translations by Lockhart, taken as a whole, there are yet some few cases in which they have been even surpassed. Thus there is another fine ballad derived from the age of Charlemagne, “Lady Alda’s Dream,” Lady Alda being the fabulous bride of the scarcely less fabulous Roland. Of this, Mr. Ticknor observes that in its English dress Lockhart must yield the palm to another most accomplished man who is still preserved to us; I mean the former Governor of Canada, Sir Edmund Head. In this ballad Lady Alda, being left at Paris with her train, has a dream of a falcon overpowered by an eagle. One of her damsels seeks to interpret this dream in an auspicious sense. But I will leave Sir Edmund Head to continue the tale:

“‘Thou art the falcon, and thy knight is the eagle in his pride,

As he comes in triumph from the wars, and pounces on his bride.’

The maidens laughed, but Alda sighed and gravely shook her head:

‘Full rich,’ quoth she, shall thy guerdon be, if thou the truth hast said.’

’Tis morn; her letters stained with blood the truth too plainly tell,

How in the chace of Ronceval Sir Roland fought and fell.”

But I have not yet done with the Admiral Guarinos. In the passage which I read to you from “Don Quixote,” you will observe how Cervantes makes his hero declare that he can expect no good fortune that day, since it had begun by the singing of a ballad upon Roncesvalles. It appears then that the singing of a ballad upon Roncesvalles was deemed of ill augury among Spaniards. On the other hand, since, as I have lately shown you, the soldiers of William the Conqueror marched forward to the battle of Hastings singing another of these ballads upon Roncesvalles, we may conclude that it was deemed of good augury among Frenchmen. Is not this a strange fact?—I think not hitherto noticed. Here are the songs on the rout of Roncesvalles held to be ill augury among the supposed descendants of the victors, and of good augury among the supposed descendants of the vanquished! Surely this is the very reverse of what on any pre-conceived idea we might expect to find.

In English poetry we find the rout of Roncesvalles not unfrequently mentioned. There is in the first book of “Paradise Lost” a reminiscence—no doubt high-toned and sonorous, but a little misty—in which Milton ranks not only the famous Roland, but the great Emperor himself among the slain:

“When Charlemagne with all his peerage fell by Fontarabia.”

Coming to later times, we find a pathetic ballad by Matthew Gregory Lewis, entitled “Durandate and Belerma,” for which he is only in some part indebted to the Spanish. It begins as follows:

“Sad and fearful is the story

Of the Roncevalles fight;

On that fatal field of glory

Perished many a gallant knight.”

Nor can you have forgotten the beautiful opening of that poem, one of the very finest of its class, which commemorates the death of the Black Prince at Bordeaux, and which Sir Walter Scott has interwoven with the novel of “Rob Roy”:

“O for the voice of that wild horn

On Fontarabian echoes borne,

The dying hero’s call;

That told imperial Charlemagne

How Paynim sons of swarthy Spain

Had wrought his champion’s fall.”

Pass we to Italian. Dante has a passage very similar to Milton’s, in which he refers to “the dolorous rout,” la dolorosa rotta, and to the sounding of the terrible horn. It is remarkable that in the same place Dante calls the enterprise of Charlemagne “the saintly deed,” la santa gesta—a phrase derived, as I conceive, from a later period—the Crusades—when the recovery of the Holy Sepulchre suggested the idea of every conflict with the Moslem as a holy war.

But in Italy the legends of Charlemagne did not merely, as in England, give rise to some passing allusion or to some imitative song. On the contrary they produced two great epic poems, the epic of Boyardo and the epic of Ariosto, both having for their hero the brave Roland, or, as the Italians call him, Orlando.

The poem of Boyardo, founded on an imaginary siege of Paris by the Saracens, is now very little read, at least beyond his own country. But the few among us who are qualified to judge, have judged him very favourably. Thus speaks Mr. Hallam:

“The ‘Orlando Inamorato’ of Boyardo has hitherto not received that share of renown which seems to be its due, overpowered by the splendour of Ariosto’s poem.”

Ariosto’s poem has indeed cast into the shade nearly all other poems of romantic fiction on his side the Alps. So much was it read and relished by the Italians as to reflect a share of its own popularity on the older Carlovingian legends, out of which it sprung.

This Italian appreciation, from whatever cause arising, of the Carlovingian legends, may be proved by some slight but significant examples. Thus is it not curious that the common Italian word which means “to deceive,” ingannare, is held to be derived from the name of Ganelon, or shortly, Gan, the arch-traitor at Roncesvalles?

Thus, again, many a wayfarer on the old and beautiful post-road—seldom, I fear, to be re-travelled—from Florence to Rome, by way of Terni, may have noticed to his left, perched on one of the summits of the Apennines, the decaying town of Spello. One of its gates bears, it seems, a piece of medieval sculpture, with an inscription in honour of Orlando. They are marked by the grossness of a less cultivated age; and I cannot fully explain them. It may suffice for my purpose to say that they are intended to commemorate the hero’s gigantic size and warlike prowess.

In France, the poems belonging to the Carlovingian cycle are very numerous, and some of considerable length. They were called “Chansons de Geste,” an old French word derived from the Latin Gesta, so that the meaning is: “Songs of heroic deeds.” One of the chief of these is the “Chanson de Roland,” having for its author Turold or Théroulde, and for its date, as is probable, the eleventh century. The last and best edition of it was in the year 1851, by M. Génin, who prefixed an ably written and interesting introduction, to which in my present essay I am much beholden.

M. Génin, in the true spirit of a commentator, ascribes great poetical merit and beauty to the work which he has edited. Such is also the opinion of a gentleman in this country, Mr. Ludlow, who in 1865 published two volumes of the “Popular Epics of the Middle Ages.” Mr. Ludlow there says that he considers the Song of Roland “the masterpiece of French epic poetry.” For my own part, I cannot concur in these praises. So far as I have read in the Song of Roland, I have found it very tiresome reading, and discovered no trace of poetical beauties. Its value, as it seems to me, is as illustrating the temper and the manners of the time; and of these I shall now proceed to offer one or two examples.

In the fifth book of the “Chanson de Roland” is an account of the final conflict under the walls of Saragoza. We find the “Amiralz” or Emir before it commences invoking his false gods, calling in one breath upon Apollo and Mahomet, and vowing to each an image in fine gold. And after the city is taken the poet continues in a passage which may serve to show the idea of liberty of conscience as current in that age:

The Emperor has Saragoza taken;

A thousand Frenchmen search through the city,

Its synagogues, and its Mahoundries (Mahumeries);

Holding mallets of iron and hatchets,

They break the images and the idols.

The Bishops meanwhile bless the waters,

And lead the pagans to the baptistery.

If any one should gainsay great Charles,

He is hanged, or burned, or slain.

More than one hundred thousand are baptized

And made good Christians; all but the Queen—

She is led away a captive to fair France,

That she may be converted by love.”

The authors of these poems were disposed to follow a good old Oriental precedent. When in the East one of the “Arabian Nights” or some other tale of wonder is recited, it is usual for the reciter to stop short at the most interesting period, and declare that he will not finish the story unless a piece of money be put down by every person present. Just so in these “Chansons de Geste.” Thus in “Huon de Bordeaux,” there is a pause after five thousand lines, when Huon is just about to encounter the giant in his castle, and the minstrel says—I will translate the lines:

“Oh mighty Segnors, I am sure you see full plain

That it is near vespers, and that I am weary.

* * * * * *

Let me then go and drink, for such is my desire.

* * * * * *

But do you return tomorrow, after dinner,

And let me pray each of you to bring with him

A maille (a halfpenny) tied up in a fold of his shirt

For there is little liberality in these Poitevines;

Miserly and mean was he who first had them made,

Or who first gave them to the courteous minstrel!”

Poitevines, let me explain, are a very small French coin, so called because they were first coined in Poitou. Small as they were, however, it was found worth while to counterfeit them, for we find in old French the word Poitevineur as applied to the maker of false Poitevines.

But I come back to the minstrel in “Huon de Bordeaux.” It would seem that his hearers on the morrow had neglected to bring in their shirts the much-desired mailles. Therefore after some five hundred lines of further recitation, the minstrel breaks forth again:

“Take you notice, so may God give me health,

I will at once put an end to my song:

I will excommunicate on my own authority,

Also by the power of Auberon and his rank,

All those who shall not open their purses and give to my wife!”

Auberon, I need not say, is the old French form of the German or the English Oberon. But I may add that in the course of my reading I have met with this name Auberon in the French form upon only two occasions, first in the legend of the Fairies, and next in the pedigree of the Earls of Carnarvon.

The story in this “Chanson de Geste,” “Huon de Bordeaux,” is substantially the same as that in the romantic poem the “Oberon” of Wieland. But its recital is extremely rude and bold, and it seems still more so when contrasted with the masterpiece of the graceful German.

One of its peculiarities is as to the parentage of Oberon, which it states at the outset in some lines as follows:

“Know ye that Auberon was son of Julius Cæsar,

Who reigned in Hungary, a savage land,

Who held Austria also, and its inheritance.

Moreover, he held court in Constantinople,

And there built walls seven leagues in length,

Which are standing at this very day.

* * * * * *

His son, then, was Auberon, the noble knight,

Who was only three feet in his stature,

But was a fairy, as you ought to know.”

A publication of these “Chansons de Geste,” under the name of “Les Anciens Poètes de la France,” was begun in 1859, with the liberal patronage of the Imperial Government, and under the able direction of M. Guessard. In 1859, and the subsequent year, there were five volumes of this series published belonging to the Carlovingian cycle. Several more have more recently appeared, and it is announced on the flyleaf that to complete that cycle no less than forty volumes in all will be required. I hope, however, that this only too liberal promise may not be carried out. The few volumes already given to the world seem to me sufficient to satisfy even the most craving curiosity. There is little variety in the stories, and none at all in the style. The poetical beauties, if indeed any exist, are at all events but thinly scattered; and the sole value of these works lies as I conceive in the glimpses which they now and then afford of the manners and feelings of the age of chivalry during which they were composed.

Those glimpses are not very favourable. The knights and Paladins, though properly held forth as fearless, appear in at least an equal degree ferocious. Moderation in conquest, and mercy to the vanquished, are seldom to be ranked among their virtues. The prelates are represented not as ministers of the God of Peace, but rather as doughty champions, seeking to kill as many Saracens as possible. For example, we find in “Gaufrey,” a French chief, Berart, address the Archbishop of Rheims as follows:

“ ‘Turpin, Sir Archbishop, be a knight today;

It is a trade in which you are already skilled.

Let you and me try our might against the pagans!’

And Turpin made answer: ‘So let it be,

I shall read them a very dolorous psalm-book,

One cannot every day be reading texts and versicles;

Times come when one should strike with one’s trusty steel!’”

So then Berart and the Archbishop rushing forward deal fierce blows upon the enemy:

“Of Saracens they made more than one hundred fall,

Who will not stand up again either in March or in February.”

As to the ladies, I may cite also from “Gaufrey” the description of Flordespine, who is represented as a pattern princess:

“Her age was but fourteen years and a half:

She knew well how to speak Latin, and she understood Romane;

She knew well how to play at tables (or draughts) and chess;

And as to the course of the stars and shining moon,

She knew more than any woman living in this age.”

The princesses were no credit to this excellent training. Not only did they on occasion bear arms and strike blows like the Bradamant of Ariosto, but they too frequently appear both treacherous and cruel. Thus, in “Fierabras,” one young lady dreading some evil machinations from her aged governess, lures her close to a palace window, and then makes a sign to her chamberlain behind, who flings the matron out of window into the sea, where she is drowned. The same princess, the beautiful Floripas, is afterwards consulted by her father, the Emir, as to the disposal of some French knights, his prisoners:

“‘So tell me then, my daughter, what counsel you give me.’

‘Sir,’ said Floripas, ‘hearken to my words:

Have their feet and their limbs cut off,

And burn them in a fire outside the city.’

‘Daughter,’ said the Emir, you have spoken right well.’”

These gentes pucelles cannot by any means be accused of carrying to excess their feelings of maiden reserve. When Floripas becomes enamoured of Gui de Bourgogne, she does not scruple to ask his hand in marriage. Gui at first objects, saying, that he will take no wife except from the choice of Charlemagne. But Floripas rejoins:

“I swear by Mahomet, that if you will not take me

I will have you all hanged and waving in the wind.”

And upon this Gui very naturally yields.

In view of this auspicious event we find that Floripas consents to adopt the Christian faith. We cannot say, however, that her ideas of female propriety are in consequence very much improved. She has to undergo a siege in one of her castles with the knights who were recently her father’s prisoners; and although they have no fear that the donjon will be taken, they apprehend a wearisome blockade. Upon this Floripas has an expedient for beguiling the time:

“I have with me five maidens of right noble birth,

What can I say more? Let each knight take a paramour,

Then so long as we are here, we shall lead a joyous life.”

This proposal finds great favour among the five knights:

“ ‘Certes,’ answered Roland, you have spoken courtesy,

Never yet saw I a maiden of such noble behaviour.’”

The devotion expressed in these “Chansons de Geste” is indeed of the most grovelling kind, and worthy of the darkest ages. It scarcely soars above the worship of the negro on the coast of Guinea for his fetish, adoring it when he is prosperous, and threatening or even maltreating it when he thinks that is does not yield him due protection. I will give two instances from this same poem of “Fierabras,” the one as applied to a Mahometan, and the other to a Christian prince. First, then, of the Emir with whom we have already made acquaintance as the father of Floripas. Being worsted in battle, he exclaims:

“Ah, Mahomet! Sir, how you have forgotten me!

Ill love have you shown me this day.

If ever I return in safety to Spain,

You shall be so beaten in the ribs and sides

That there is no man in the world but will pity you;

And I shall hold you more vile than any dead dog.”

Let us come next to the mighty Emperor Charlemagne himself:

“‘St. Mary, our Lady,’ said Charles of the haughty aspect,

‘Protect Oliver, so that he may not be killed or taken;

For, by my father’s sword, if he were slain,

In no monastery of France nor yet of other lands

Should priest or clerk be any more ordained:

I would cast down both crucifix and altar!’”

Charlemagne himself appears wholly transfigured in these “Chansons de Geste.” First he is represented as in extreme old age. Thus in the opening passage of “Huon de Bordeaux,” he is made to say that he was a hundred years old at the birth of his eldest son Charlot, who is already grown up to manhood. Thus, again, in “Doon de Mayence,” we are told that Doon and Charlemagne were born on the same day, and yet Charlemagne survived to be also the contemporary of a grandson of Doon, no other than the traitor Ganelon.

In conformity with the idea of decrepid age, the “Chansons de Geste” no longer hold forth Charlemagne as the wise and mighty sovereign, such as he is shown both in the earlier fictions, and in authentic history. On the contrary, he is represented as feeble and fretful, timorous and wavering, and bearded even to his face by his bolder Paladins. There is among several others, one curious dialogue of this kind in “Gui de Bourgogne,” the scene being laid in Spain. The great Emperor is so nettled by a taunt from Roland, that he nearly, says the poet, struck him with his glove across the nose:

“‘Sir,’ so spoke Oliver, ‘ you are much to blame,

And I swear that I will not let seven days pass by

Before I begin my march homewards to France.’

* * * * * *

‘By my head,’ quoth Roland, ‘I will do the same.

Let us leave this old man, who is wholly besotted,

And may a hundred thousand devils possess him!’”

The constant and as it were systematic depreciation of Charlemagne in these later poems might well surprise us. Perhaps it is best explained by remembering how, since the time of Charlemagne, the great feudatories of the Crown had succeeded in depressing both his own descendants and the first kings of the succeeding dynasty. A feeble monarch surrounded by powerful and overbearing vassals, might seem, at least to the dependents of the latter, the most eligible form of government. Hence it would be natural for them to suppose that in the time of the far-famed Emperor also a like system had prevailed. The poet makes Roland address to Charles the Great the same terms as the Comte de Vermandois may really have addressed to Charles the Simple.

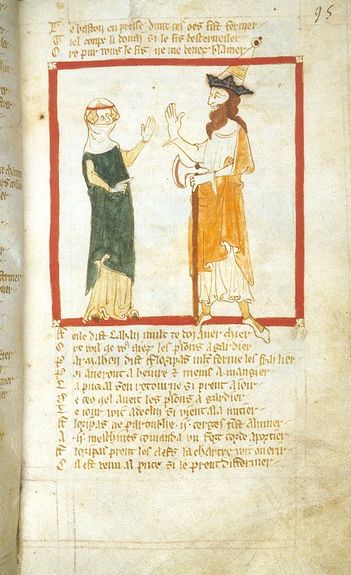

Besides the “Chansons de Geste” there exists a wholly separate class of poems relative to Charlemagne, which is made known to us in some detail by M. Louis Moland in his “Origines Littéraires de la France.” These poems belong to the literature and were prompted by the spirit of the first Crusades. Assuming a pilgrimage to the Holy Land as amongst the highest of earthly duties, and taking for granted that the mighty Charlemagne could not have neglected that sacred obligation, they represent him as visiting both Constantinople and Jerusalem in company with his twelve peers. The principal composition of this class, extending to nearly nine hundred lines, dates from the twelfth century. There is a transcript of it in the fifteenth, which is preserved at the British Museum, and which is illustrated with admirable skill. It contains for example, on the verso of one of the first folio pages, a superb miniature representing John Talbot, the first and famous Earl of Shrewsbury, who, on his knees, is supposed to present this very volume to Queen Margaret of Anjou.

It was from this transcript at the British Museum that the poem was published for the first time in 1836, by a French gentleman well known in antiquarian literature, M. Francisque Michel. Fully sufficient extracts, however, will be found in the work of M. Moland.

I will here translate the lines describing what Charlemagne found in the temple of Jerusalem,

“He entered a church of marble, richly painted.

There stood an altar of renowned sanctity:

At this Christ had chaunted the Mass, and His Apostles also.

And the twelve stalls are still there entire,

The thirteenth in the midst, sealed and closed.

Charles came in, rejoicing at his heart.

The twelve peers took their seats on both sides,

But Charles took his seat in the midst.

No man ever sat there before him!”

Such then were the legends of Charlemagne. I certainly cannot commend them to my hearers as a rich and fertile field from which an abundant harvest may be gathered in. They rather, on the contrary, resemble some rude moorland, or some thicket full of briars, upon which, nevertheless, a few berries may be found. Dropping metaphors, I would say that while I am unable to discern in these poems any of the beauties ascribed to them by their more ardent commentators, and while I think that their stories are for the most part ill-contrived and destitute of interest, I yet conceive that they afford very striking illustrations—and the more striking because wholly undesigned—of the customs and the feelings in the “age of chivalry”—which was never very chivalrous in the modern sense of the term.