Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Military Heroes of the United States, by Hartwell James (published 1899).

Anthony Wayne, a brilliant officer of the Revolution, and afterwards commander-in-chief of the armies of the United States, was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, January 1, 1745. His early education was at the hands of a relative, and afterwards at the Philadelphia Academy, where he appears to have distinguished himself in mathematics. It is also said of him that he had a liking for military studies as well. Leaving school at seventeen years of age, he became a farmer and land-surveyor, and was married five years later.

When the colonies grew restive under the oppressive measures of Great Britain, Wayne openly declared that hostilities would follow, and immediately began to raise volunteers for the war which he deemed inevitable. Congress made him a colonel when his prediction became true, and his first service was in Canada. He was wounded at Three Rivers, and then commanded at Fort Ticonderoga, joining Washington in New Jersey in 1777. He was now a brigadier-general, and had been complimented for distinguished bravery and skill.

Wayne bore a conspicuous part at Brandywine, and at Germantown his horse was shot under him. In this last battle he covered the retreat of the Americans. Subsequently, at Valley Forge, Wayne commanded a foraging expedition and brought much relief to the destitute army in, the shape of cattle and provisions of various kinds. At Monmouth, Wayne distinguished himself by his bravery, and was commended by Washington in his official letter to Congress.

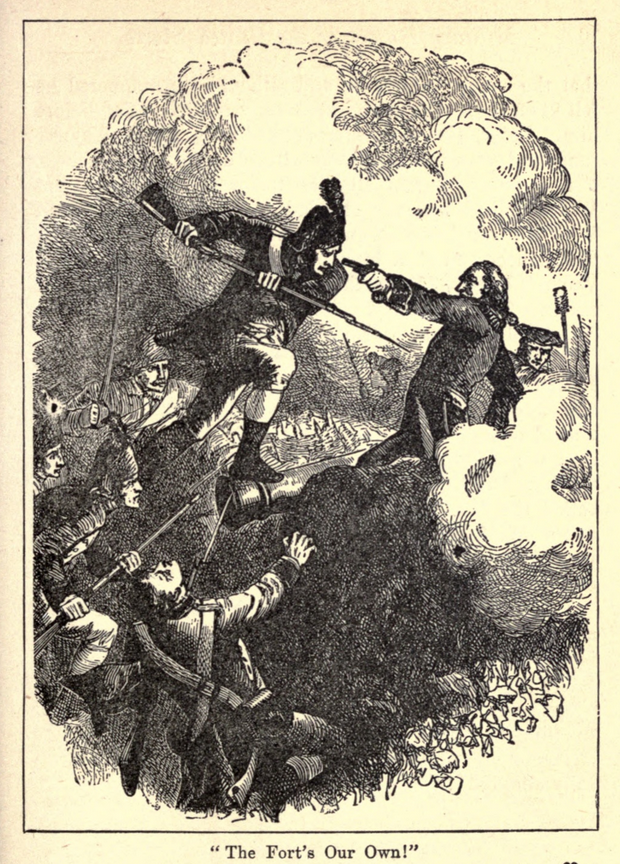

The storming of Stony Point, on the Hudson River, was assigned to General Wayne, and he successfully carried the position by assault, shortly after midnight of July 15, 1779. Its natural defenses had been strengthened, and, with its strong garrison, was regarded as almost impregnable. Wayne divided his forces into two columns, and each man at the same time was ordered “to fix a piece of white paper in the most conspicuous part of his hat or cap to distinguish him from the enemy,” and a watchword, “The fort’s our own,” was communicated to each, with orders to give it “with repeated and loud voice when the works were forced, and not before.” Scaling the parapet, and creeping through the embrasures on either side, the assailants raised the cry agreed upon, and drove the garrison before them, notwithstanding the most desperate resistance was offered. While this terrible hand-to-hand contest was raging within the fort, Wayne, who had been wounded in the head by a musket ball, was lying near the spot where he fell; but when the enemy had surrendered, as it soon did, he was carried into the fort, “bleeding, but in triumph.” Three hearty cheers from his victorious troops formed the salute under which the daring general was carried into the fort to receive the submission of the garrison, and again “The fort’s our own!” broke out in the inspiration of the moment.

In 1781, Wayne was with Lafayette in Virginia. Lafayette ordered him to attack the rear guard of Cornwallis’s army, thinking the main body had passed over a river.

Wayne fell upon the British as directed, but found it to be the army itself. Grasping the situation, he made such a vigorous charge that Cornwallis thought the entire American army was upon him and began to prepare for a general engagement. Under cover of his movements Wayne was able to withdraw his troops, thus extricating them from a perilous position.

After the surrender of Yorktown, Wayne joined General Greene and operated in Georgia, where the British outnumbered him three to one. But his indomitable spirit rose above every obstacle, and he drove the enemy from one point to another until he virtually wrested the state from the British. In speaking of this campaign, Wayne said:

“The duty we have done in Georgia was more difficult than that imposed upon the children of Israel; they had only to make bricks without straw, but we have had provision, forage, and almost every other apparatus of war to procure without money; boats, bridges, etc., to build without materials, except those taken from the stump; and what was more difficult than all to make Whigs out of Tories. But this we have effected, and have wrested the country out of the hands of the enemy, with the exception only of the town of Savannah.”

Two tribes of Indians, the Choctaws and the Creeks, had been induced to join the British forces. Wayne fell upon and completely routed the former and then turned his attention to the Creeks. He instructed his men to rely entirely upon the bayonet and the sword, and led them to a defile through which the enemy must pass. Wayne and his men reached the pass at the same time that the enemy entered it, and although outnumbered he fell upon them with such impetuosity that they fled before him. Later, the Creeks crept stealthily up to Wayne’s camp and with a terrible war-whoop drove in his pickets. For a few moments all was terror and confusion, but Wayne rallied his men and led them against their foes. With his own hand he cut down a tall chief, who, in his death throes, fired at him, but missed his aim and killed Wayne’s horse. The conflict was a short one, and soon the savages fled in dismay. Shortly afterwards the British evacuated Savannah and peace soon followed.

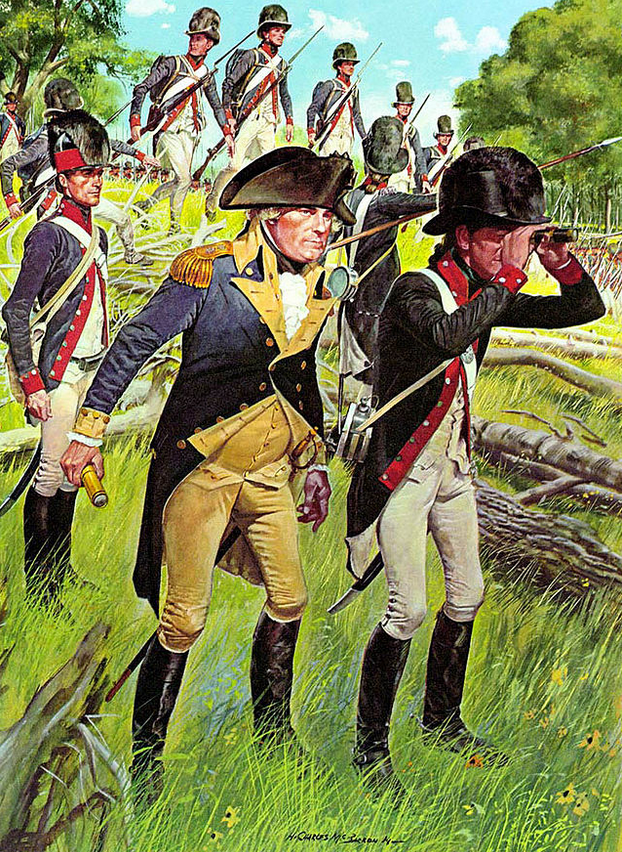

Wayne was not allowed to rest in peace, however. An Indian war followed that of the Revolution, and Wayne was made commander-in-chief of the army. He conducted operations so well that a long peace with the red men was effected. Wayne’s death came while exercising the functions of an Indian Commissioner in what was then called the Northwest. He died on December 14, 1796, at Presque Isle, and was buried there, but later his remains were removed to his native county and a monument was erected to his memory.

Wayne was one of the most popular men in the army, and was known the country over as “Mad Anthony.” It is said that “this name was originally given by a witless fellow in the camp, who used always to take a circuit when he came near Wayne, and, shaking his head, mutter to himself, ‘Mad Anthony! mad Anthony!’ It was so characteristic of Wayne, however, that the troops universally adopted it.”