Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Beneath the Banner: Being Narratives of Noble Lives and Brave Deeds, by F.J. Cross (published 1895)

John Coleridge Patteson was born in April, 1827. He was blessed with an upright and good father, and a loving and gentle mother; and thus his early training was calculated to make him the earnest Christian man he afterwards became.

Here is an extract from a letter written from school at the age of nine, which shows that he had faults and failings to overcome just like all other boys:—

“My dear papa, I am very sorry for having told so many falsehoods, which Uncle Frank has told mama of. I am very sorry for having done so many bad things—I mean falsehoods—and I heartily beg your pardon; and Uncle Frank says that he thinks if I stay, in a month’s time Mr. Cornish will be able to trust me again…. He told me that if I ever told another falsehood he should that instant march me into the school and ask Mr. Cornish to strip and birch me … but I will not catch the birching.”

And he did not. He was so frank, so ready to see his own faults, that he was always a favourite. Uncle Frank remarked of him at this same time: “He wins one’s heart in a moment”.

Perhaps one ought to call him a Queen’s missionary, for her Majesty saved him from a serious accident in a rather remarkable manner.

In 1838 when the Queen was driving in her carriage the crowd was so dense that Patteson, then at school at Eton, became entangled in the wheel of the carriage and would have been thrown underneath and run over had it not been for the young Queen’s quick perception. Seeing the danger she gave her hand to the boy, who readily seized it, and was thus able to get on his feet again and avoid the threatened peril.

He was a boy who, when he had done wrong, always blamed himself—not anyone else. Thus, when he was twelve, having spent a good deal of his time one term at Eton enjoying cricket and boating, he found his tutor was not at all satisfied with his progress. “I am ashamed to say,” he remarked in writing home, “that I can offer not the slightest excuse: my conduct on this occasion has been very bad. I expect a severe reproof from you, and pray do not send me any money. But from this time I am determined I will not lose a moment.”

In 1841 came the first indication of what his future career might be.

Bishop Selwyn of New Zealand was preaching, and the boy says of the sermon: “It was beautiful when he talked of his going out to found a church, and then to die neglected and forgotten”.

How deep had been the influence on his mind of his mother’s example may be gathered from the letter he wrote at the time of her death in 1842, when he was fifteen years old: “It is a very dreadful loss for us all, but we have been taught by that dear mother who has now been taken from us that it is not fit to grieve for those who die in the Lord, ‘for they rest from their labors’…. She said once, ‘I wonder I wish to leave you, my dearest John, and the children and this sweet place, but yet I do wish it’; so lovely was her faith.”

In 1854 Bishop Selwyn returned to England. During the time that had elapsed since his previous visit, Patteson had been ordained. The bishop stayed with his father a few days, and during that time the feelings which the boy of fourteen had experienced were revived in the man of twenty-seven; and with his father’s consent John Coleridge Patteson entered upon his life work, sailing with Bishop Selwyn for the South Seas in March, 1855.

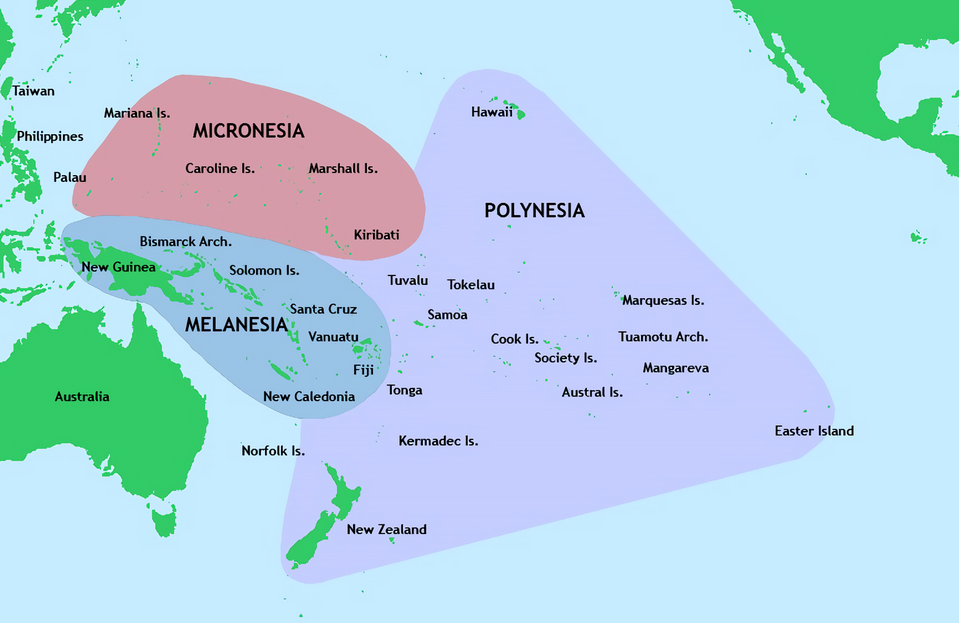

There he labored with such energy and success that in 1861 he was consecrated bishop. Many thousands of miles were traversed by him in the mission ship The Southern Cross, visiting the numerous islands of the Pacific known as Polynesia or Melanesia.

Of the dangers that abounded he knew ample to try his courage. On arriving at Erromanga (the scene of Williams’ martyrdom) on one occasion he found that Mr. Gordon, the missionary, and his wife had recently both been treacherously slain by the natives. At another island, as he returned to the boat, he saw one of the natives draw a bow with the apparent intention of shooting him, and then unbend it at the entreaty of his comrades. “But,” remarks the bishop in recording this, “we must try to effect more frequent landings.”

And thus full of faith he labored on, telling the people of these scattered islands, which besprinkle the southern ocean like stars in the milky way, of the love of Christ.

He was still ready to condemn himself just as he did in his early days. From Norfolk Island, in 1870, he wrote to his sister when he was holding an ordination: “At such times as these, when one is specially engaged in solemn work, there is much heart searching; and I cannot tell you how my conscience accuses me of such systematic selfishness during many long years—I mean I see how I was all along making self the centre, and neglecting all kinds of duties—social and others—in consequence”.

He was much grieved by the accounts which reached him of the terrible war which was being fought between France and Germany in 1870. “What can I say,” he writes, “to my Melanesians about it? Do these nations believe in the gospel of peace and goodwill? Is the sermon on the mount a reality or not?”

Yet he had troubles closer at home than this even. The trading ships were coming in numbers to the islands, and carrying off the natives either by guile or by force to Fiji and other places where laborers were wanted.

Notwithstanding the anxieties which beset him on this account, the good bishop continued to work as hard as ever, and very happy he was about his people.

On Christmas Eve, 1870, he writes: “Seven new communicants to-morrow morning. And all things, God be praised, happy and peaceful about us.” He wrote of the large “family” of 145 Melanesian natives he had around him; at another time he spoke of his sleeping on a table with some twelve or more fellows about him; and people coming and going all day long both in and out of school hours!

In August, 1871, he baptized 248 persons, twenty-five of them adults, all in a little more than a month, and he rejoiced in the thought that a blessed change was going on in the hearts of these people.

He had never experienced such cheering success before, and, though his friends were endeavoring to persuade him to take rest and change for his health’s sake, he determined to labor on while there was so much need for his exertion and such blessed results followed.

The desire to believe on the part of some of his people was very touching. One of them said to him: “I don’t know how to pray properly, but I and my wife say, ‘God make our hearts light—take away the darkness. We believe that You love us because You sent Jesus to become a man and die for us; but we can’t understand it all. Make us fit to be baptized.'”

Some, of course, were not so enlightened as that. After the kidnapping traders had been harrying the islands, one of the chiefs said that, if the bishop would only bring a man-of-war and get him vengeance on his adversaries, he would be exalted like his Father above.

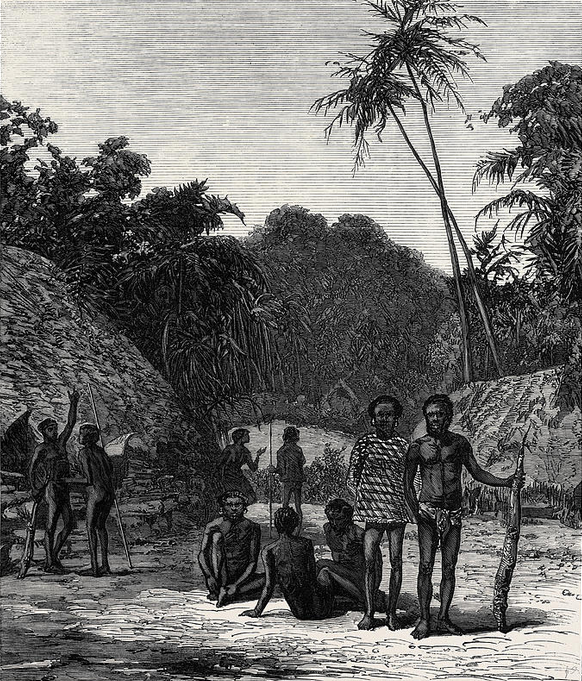

There was indeed serious cause for the anger of the natives. One of them related how he had been out to a vessel with his companions, and a white man had come down into the canoe and presently upset it, seizing him by the belt. Happily this broke, and he swam under the side of the canoe and finally got on shore, but the other three were killed—their heads were cut off and taken on board, and their bodies thrown to the sharks. The assailants were men-stealers, who killed ruthlessly that they might present heads to the chiefs.

Five natives from the same island were also killed or carried off, and thus when the bishop visited them they were in a state of sullen wrath.

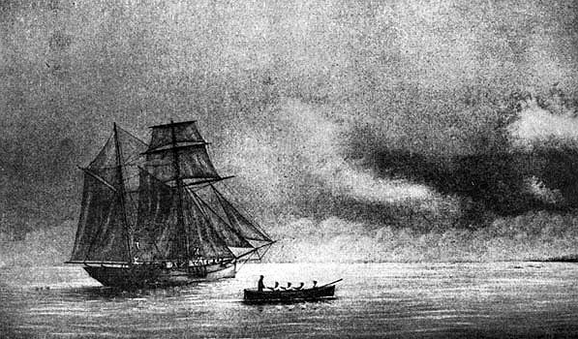

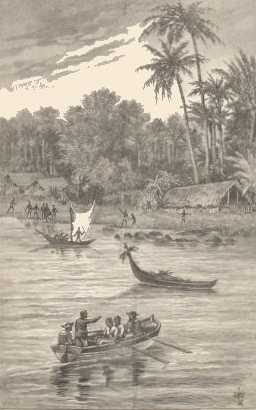

On the 20th of September, 1871, Bishop Patteson came to Nukapu. The island is difficult of approach at low water, and the little ship, The Southern Cross, could not get close in. So the bishop went off to the shore in a boat and got into one of the canoes, leaving his four pupils to await his return. They saw him land, and he was then lost to sight.

About half an hour later the natives in the canoes, without the least warning, began shooting their arrows at the poor fellows in the boat, and ere it could be taken out of bowshot one of them was pierced with six arrows, and two of the others were also wounded.

They were full of fears about the bishop, and, notwithstanding the danger, determined to seek for him. They had no arms except one pistol which the mate possessed.

As they made their way towards shore a canoe drifted out, and lying in it, wrapped in a native mat, was the body of Bishop Patteson.

A sweet calm smile was on his face, a palm leaf was fastened upon his breast, and upon the body were five wounds—the exact number of the natives who had been kidnapped or killed.

So the good bishop died for the misdeeds of others. The natives but followed their traditions in exacting blood for blood, and their poor dark minds could not distinguish between the good and the bad white men.

Two of those who were with the bishop in the boat, and had received arrow wounds, died within a week, after much suffering.

One of them, Mr. Atkins, writing of the occurrence on the day of the martyrdom, says:—

“It would be selfish to wish him back. He has gone to his rest, dying, as he lived, in the Master’s service. It seems a shocking way to die; but I can say from experience it is far more to hear of than to suffer. There is no sign of fear or pain on his face, just the look that he used to have when asleep, patient and a little wearied. What his mission will do without him, God only knows who has taken him away.”

Three days after, in celebrating the Holy Communion, Mr. Atkins stumbled in his speech, and then he and his companions knew the poison in his system was working. “Stephen and I,” he said, “are going to follow the bishop. Don’t grieve about it … It is very good because God would have it so, because He only looks after us, and He understands about us, and now He wills to take us too and it is well.”