Editor’s Note: The following account, written by Jim Marshall, is from The 100 Best True Stories of World War II (published 1945)

From the sweltering north, the Tokyo Express sped silently southward toward Guadalcanal – six or eight sub-stacked destroyers, possibly a couple of cruisers, half a dozen or more cargo ships packed with men, gasoline, shells, bombs, food and supplies for the doomed garrison on the island. Up from a South Pacific base our American Thunderbolt raced northwestward to meet the Express.

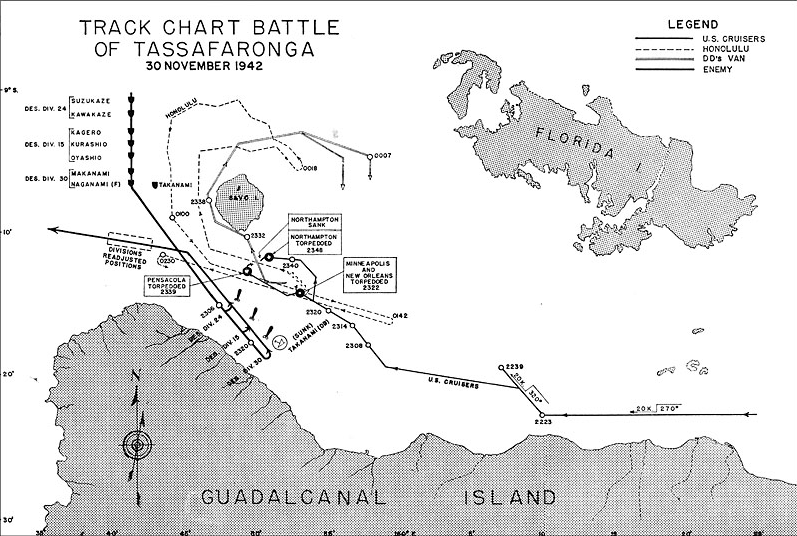

As the Japs came down west of Savo Island, our five cruisers knifed along in the channel between Guadalcanal’s northern coast and the dark bulk of Florida Island, over to starboard. There was a destroyer screen ahead, another aft. In both forces, keen eyes scanned and strained through night glasses; sensitive ears sought the telltale sounds that might come at any moment now.

In the ships, hundreds of men – boys from Japanese fishing villages and rice farms, lads from the Alabama cotton country and the Louisiana bayous, waited out their last few minutes of life before they sent one another to death in a hell of steel, fire and water.

This thing had started more than a day before, when Admiral Halsey’s air scouts had reported the Express on the way. So many ships of this and that class, course so-and-so, speed so many knots, destination: Guadalcanal. Halsey studied his charts, figured currents and tides, made up his orders to his task force. It would proceed on a certain course at a certain speed; if any ships discovered an enemy within six thousand yards, they would open fire without any further orders. It was estimated that the Express and the Thunderbolt should meet around a certain spot on the chart, about a day and a half ahead.

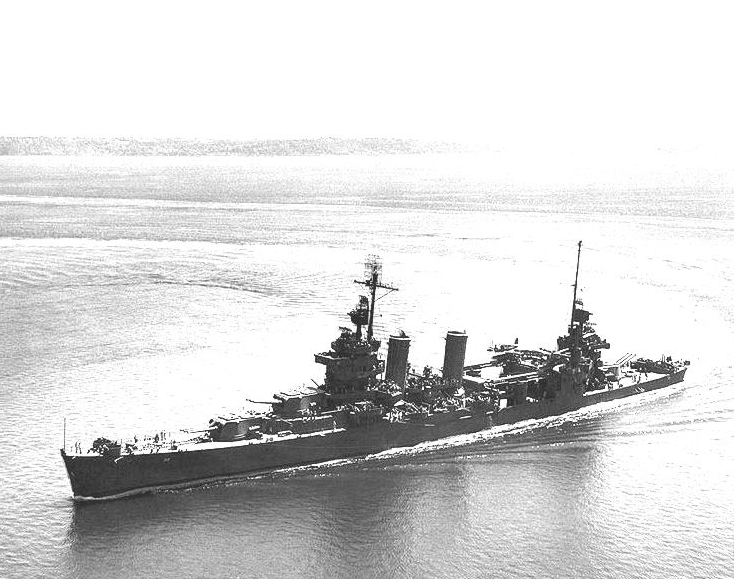

It was very dark, with a smooth sea, a light wind and a heavy overcast. Our force of five cruisers included the New Orleans, Pensacola, Northampton and Minneapolis. The Japs were later to report three of these ships sunk. They were wrong – by two.

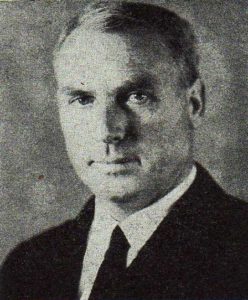

On the bridge of the New Orleans, Commander Oliver F. Naquin navigated the vessel. Captain C. H. Roper was in command and took charge. Naquin, a New Orleans man himself, had survived the sinking of the submarine Squalus, and the hell aboard the battleship California in Pearl Harbor. Tonight, he was going to need all the luck and resourcefulness that had brought him through those two disasters. Tonight was going to be worse.

As the night watch started at eight bells, the men went to battle stations. The ship, keeping station in the dimming light, slide silently ahead.

Nothing happened for one hundred and sixty tense, nerve-straining minutes. Then the Japs were sighted.

They were off the port bow of our force’s vessels, steaming close inshore to the island, on an almost parallel course, but headed in the opposite direction. Against the black of the land a few star shells soared into the night.

For almost half an hour, the two forces steam silently toward each other. Then, at 11:19 the task force commander gave the fire order, and thirty seconds later a destroyer let go a salvo. In thirty seconds the Minneapolis’ first salvo was away. At 11:21 the main battery of the New Orleans, which had been loaded and ready, blasted nine shells to port, and almost at the same instant the Pensacola fired. Her ten shells chased the New Orleans’ salvo southwestward, and on the bridge of the New Orleans, Chief Signalman Harry C. Eaton, a Tulsa boy, watch the red spots of the tracer ends receding into the blackness.

The nineteen shells hit a Jap cruiser all at once, and then there was nothing at the spot where she had been. Nothing.

Commander W. F. Riggs, Jr., the NO‘s exec, smiled grimly in “Batt. Two,” the after control station, where he was in command. The guns quickly shifted to the second target – a destroyer. The destroyer vanished. A few Jap shells splashed harmlessly ahead and aft. The American’s guns shouted again and, far away toward the island, there was a terrific flash and explosion as an ammunition ship followed the cruiser and the destroyer.

At 11:27 1/2, Commander Naquin, through the flashes of his own guns, saw a ball of fire envelope the Minneapolis. She’s gone, he thought, and to his helmsman he ordered: “Hard right rudder,” to prevent ramming the slowing cruiser ahead. The NO swung out of line to eastward. She was still swinging thirty seconds later when the Jap torpedo hit.

The ship had been in action a few minutes, firing salvo after salvo from her big battery. In the next few seconds, this is what happened:

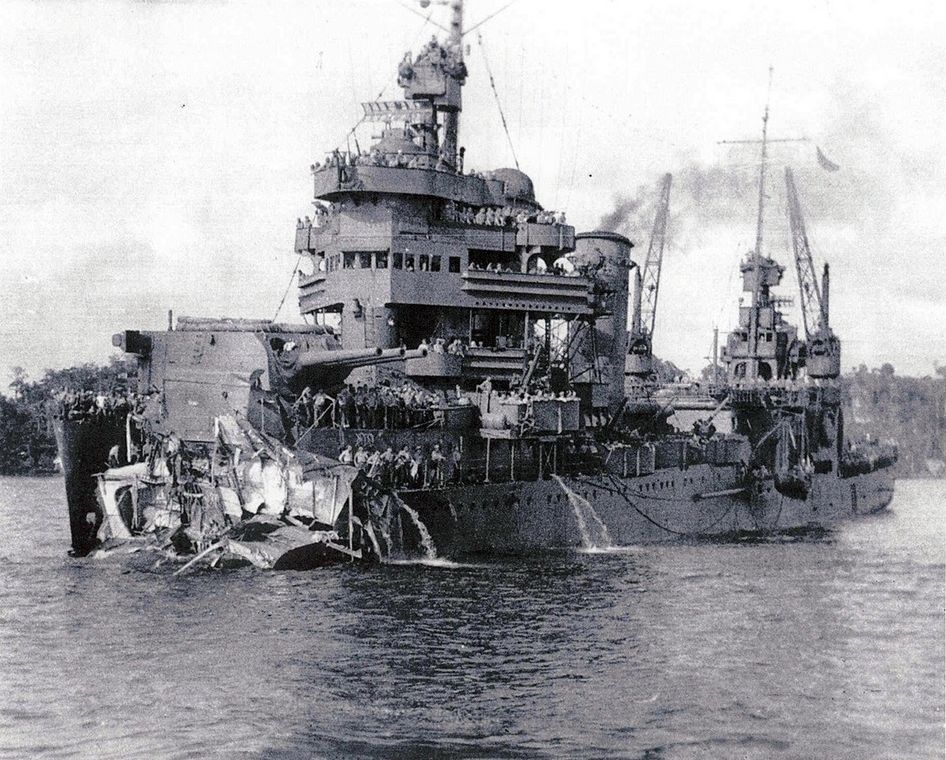

The torpedo exploded on the port side, between Turrets One and Two. This explosion detonated the magazine; the magazines set off seven thousand gallons of aviation gasoline. The triple blast – all three explosions merged into one – blew off the entire bow, about a quarter of the ship’s length. Turret Tow, just aft of the break, jammed with its guns outboard; all its men died instantly. Steering and engine controls from the pilothouse went dead. The after control station took over.

The dismembered bow still floated and, as the ship still swung, its momentum carried it aft, its three guns pointing skyward. Seconds later, the bow crashed into the port quarter of the NO, denting the plates and crippling the inboard propeller.

“That’s the first time a ship ever rammed herself, I’ll bet!” Naquin said to the men on the bridge.

The triple explosion, from aft, looked like the end of everything. “Sparks and flames shot far above the foremast,” said Commander Riggs. “A column of water rose and drenched the ship. She rocked like a loping horse. But we could still fight. A lookout reported another torpedo on our starboard quarter. We swung to port and it slid by.”

As they watch, the bow sank. Only the thin bulkheads just forward of Turret Two held back the sea. If they gave…

Damage reports came in. The ship was burning forward; she was down twenty feet by the head, with water four and a half feet over her main deck. Her speed was two knots. She was almost unmanageable, and steering had to be done by the three remaining propellers. One hundred and seventy-eight men were dead or dying; twenty-three were injured.

Lieutenant Commander Edward E. Evans of Portland, Oregon, the ship’s surgeon, was dead. The sick bay and all its patients were wiped out, but Lieutenant John Higginson, from the Mayo Clinic, had left the bay a few seconds before. He was Evans’ assistant. He and Lieutenant Commander W. M. Thomas of Independence, Missouri, who was the ship’s dentist, went to work.

Within two minutes from the time the torpedo exploded, the ship was under control again, headed for Tulagi at five knots, steering wildly, half sinking, afire and still fighting with one third of her main battery and the three quarters of her hull that remained. Five minutes later, she sighted a Jap destroyer and let him have it. He turned tail and ran.

For half an hour, the ship staggered on, the flared-out plates and dangling keel holding her back and making her yaw wildly. For some time, the boys aft didn’t know exactly what had happened. Lieutenant Francis E. Malley of New York, in charge of a repair party, went forward in the deep blackness of the ship, looking for “the hole.” Suddenly he stopped – because the stars were shining in his eyes. One more step, and he’d have been falling into the sea.

“Where’s the bow?” he asked.

“Gone, I guess,” said Ensign John A. Zehner, an Athens, Alabama, lad, who was then a boatswain and deck repairman.

Repair parties now went to work, closing sprung watertight doors, working with homemade diving masks they had made out of gas masks. The bulkheads were holding – but how long they would hold, no one knew. Some of the heavy steel plates had been twisted like paper.

Five minutes after midnight, as the NO wallowed toward the harbor on Florida Island, a Jap searchlight beam swung toward her, and she painfully turned north to avoid it. It was a bad few minutes, but the light never found her. Then a message came from the repair party: The forward bulkheads were sagging. Naquin reversed the engines and tried to get way on the ship stern first, to relieve the strain.

This failed; the ship wouldn’t steer. Down below, Commander H. S. Persons, another Alabama man, from Montgomery, saw his telegraph pointer swing again to “Slow Ahead.” He knew by now what that meant – and what would happen to the engine- and fire-room gangs if the bulkheads went. He wasn’t too sure about his engines, either.

“When the explosions came,” he said, “we were running about two hundred revolutions. The engine stopped suddenly – a complete stop – and then started again. In that minute, a lot of the machinery turned a deep blue, and we didn’t know just how badly it had been hurt. It turned out later, when we tested it, that it was in perfect condition.”

It took the ship nearly six hours to make the dozen miles into Tulagi Harbor. There commander Riggs wrote in the diary: “A long, hard night.”

On the bridge, sorting out their thoughts, the officers realized suddenly that, ironically, the torpedo which apparently had doomed the ship had in reality saved what was left of her.

For an instant, after the torpedo struck, two thousand tons of bow and guns sagged down, pulling the ship toward the bottom. Then the second and third explosions had blasted away this dead weight, severing it completely from the rest of the hull, allowing what was still afloat to regain enough buoyancy to keep it up.

Commander Naquin said to Signalman Eaton that nothing like this ever had happened before, and Eaton, who had been thrown hard to the deck by the concussion, rubbed his bruises and said, “No, sir, it never has.” That was all the comment they made; they then turned to help save the ship that had, miraculously, started to save herself.

But there was no time for rest. The New Orleans was almost defenseless. Two hundred of her crew were dead or wounded; she was open to air attack. Somehow her bulkheads forward had to be shored up, and she had to make about 1,700 miles to Sydney, Australia, open to bombs, shells and torpedoes.

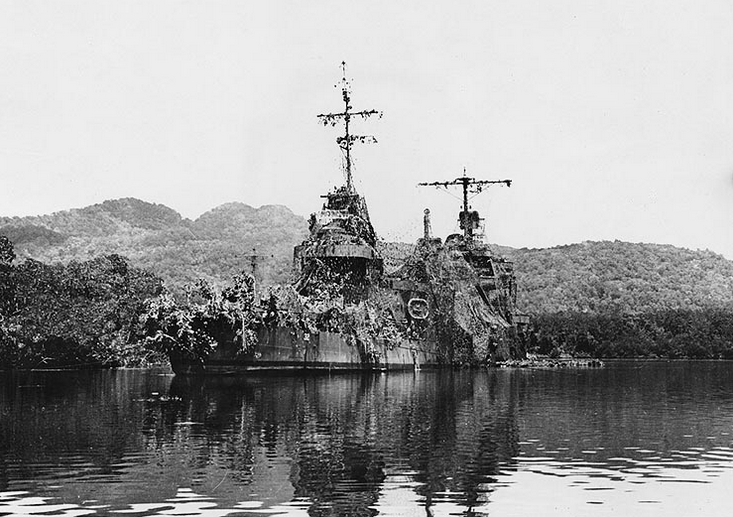

Slowly they maneuvered her across the harbor and up into a steaming jungle river, mooring her close to the bank under the mangroves. Seamen became lumberjacks ashore, felling trees and dragging them to the ship. The tops were cut off and spread over rope nets, made out of strands from heavy hawsers, for camouflage. Frequently, the sirens screamed air alerts, but the Marines over on Guadalcanal sent their fighters aloft and drove off the Jap planes, time and again.

Naquin went up in a scout plane and flew around over the ship when the camouflage job was done.

“How is it, Commander?” asked the pilot.

“It looks,” said Naquin grimly, “just like a camouflaged cruiser with her bow missing.”

One of the accompanying destroyers in the battle, Naquin remembered, was the famous Shaw, which had had her bow blown off in the attack on Pearl Harbor, and had been brought home to be fitted with a new one.

Then he came down and told the ship’s company that the camouflage was perfect. “They’ll never find us,” he said, and with one tension slackened, the work went ahead.

Bulkheads were shored up; the flaring, tortured plates forward were cut away by nearly naked divers working with electric torches. Many of the men still were suffering from concussion.

“It seemed that a sort of veil surrounded some of them,” said Lieutenant Malley. “You had to shout to make them hear.”

But they worked day and night, and early one evening the New Orleans reported ready for sea again. At 6:48 she got under way, leaving behind her dead and wounded.

The luck lasted four days this time, as the NO went zigzagging south on three engines. A Force Six storm blew up, and the shored-up bulkheads groaned, pounded by the head sea. They reversed the engines, and she struggled along, stern first, at three knots, pitching in the swells, her fantail taking it green. After a day of this, she went ahead again, taking a chance with the storm in order to get a little more speed. The gale finally blew itself out.

She eventually plowed slowly between the Heads into Sydney Harbor and tied up alongside a wharf. She was safe – for a while. Everyone was dead tired – and there were those comrades, in graves and hospitals, to sadden everyone aboard.

Meanwhile, at Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton, Washington, Rear Admiral S. A. Taffinder smoked his big corncob in the Administration Building and read the secret messages that now flowed in to disrupt his Christmas. There were few details at first – but it was plain that the yard would have to build an entire new bow and have it ready for welding to the NO when she arrived. The plans were available – the ship was one of several sisters of the Astoria class. She had come out in 1934.

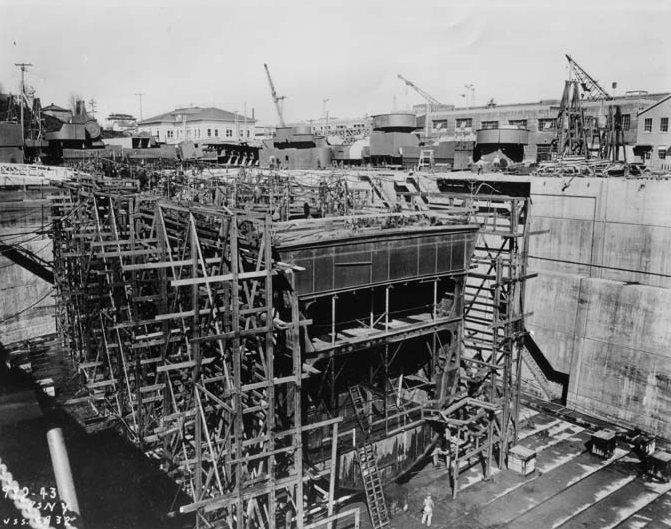

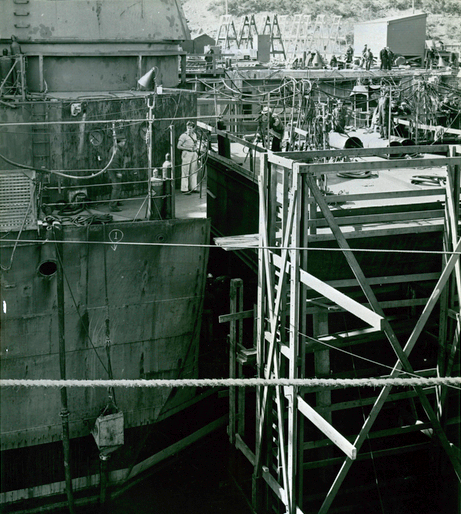

Admiral Taffinder called in Commander E. E. Sprung, hull expert of the yard, and told him the problem. Spring got to work and, a few days later, plans for the new bow had taken shape on the huge mold loft floor. Steel plates came into the yard; workmen rolled up their sleeves in the damp, clammy climate, and the first steel was laid in a dry dock. Few people in the yard knew anything. The Navy simply called it Ordship Nine.

While this was going on, another bow was being put together in Sydney. This was a temporary affair, a blunt wedge patterned after the jury bow designed for the famous destroyer Shaw, which had been similarly hurt at Pearl Harbor. It was put together of anything available; some of the interior bracing was Jap steel that was captured at Tulagi when we took that place – angle irons, light rails and so forth.

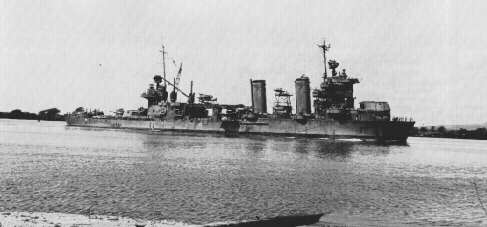

The three eight-inch rifles from Turret Two were lifted out and laid on the afterdeck, to bring the stern down and the bow up. The temporary bow was built on, slowly and painfully. Then the NO, again seaworthy, steered for home. She made around fifteen knots now and she still had three heavy guns and her secondary batteries. And she proudly wore three Jap flags for the ships she had sent to the bottom.

The Japs still claimed that she was sunk, along with the Minneapolis and the Northampton. But the badly battered “Minnie” still floated, ready to fight.

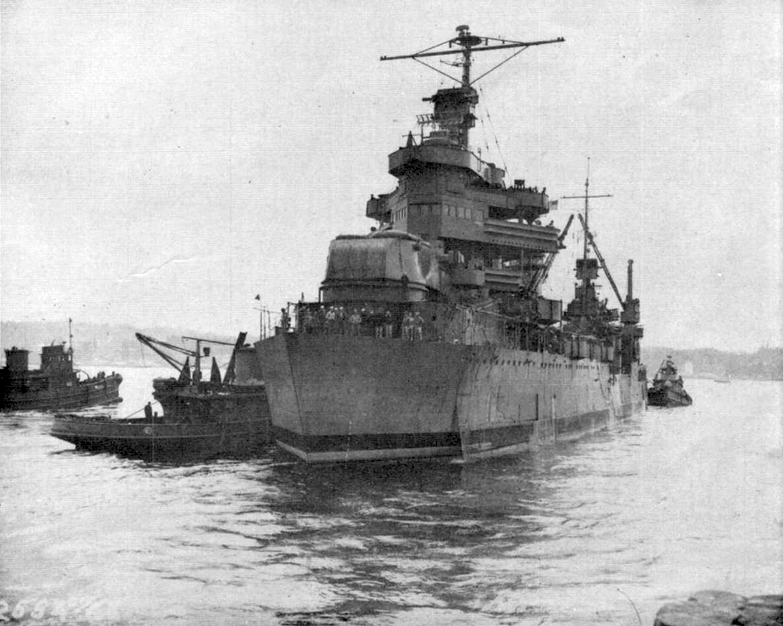

Slowly, stopping en route, the NO made her way north and east, and finally steamed past Cape Flattery and up Puget Sound into dry dock. And there was her new bow, waiting for her, and Admiral Taffinder and a crowd of yard workers.

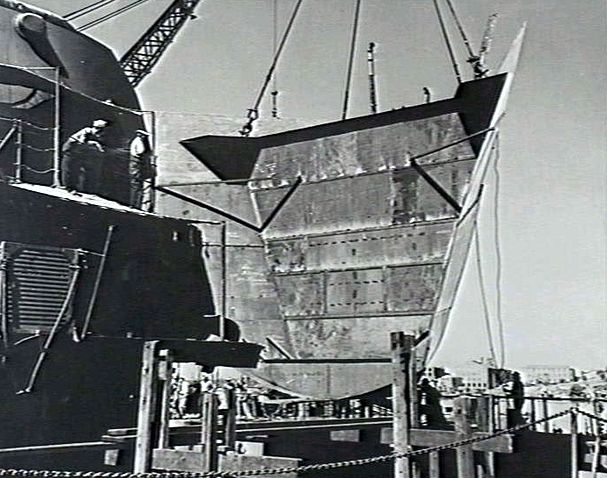

No time was wasted. Off came the temporary bow and the NO forged slowly ahead and fitted herself up against her new stem section – a replica of the section that lay on the bottom south of Savo Island, seventy-five hundred miles away.

Commander Sprung went down into the dock to see how his new bow fitted. He cussed a little. It was out almost one eighth of an inch. But when you build 1,600 tons of ship and expect it to fit exactly to some 8,000 tons of another ship which has been wracked by fire and high explosive…

“Well,” said the constructor, “I guess it’s not so bad.”

The welders went to work, and in a few days the parts were joined – the NO was whole again. Originally she had been an all-rivet job; now she was a hybrid, a quarter of her welded, and better than ever. She was part New York, where she was built originally; part Bremerton, which gave her her new section. And most of her crew came from places where they called her the N’Yawlins when they didn’t call her, affectionately, the “NO ship.”

But she wasn’t through yet. Later, a sister ship came into port, en route to Mare Island for repairs. They lifted out her No. 1 turret and laid it on a pier. Two months later, a crane picked it up and lowered it into the new bow of the NO ship.

Around the Navy Yard they tell you that the new bow wasn’t the main thing. The whole ship had been modernized; she was faster and a more deadly fighting machine than ever. Soon she was at sea again, in battle trim, looking for ’em.

So – this is the simple story of a staunch ship that torn in two and wounded almost to death, fought on and was kept alive by a gallant and determined crew; of how they saved her and brought her home to be revived and fight again.

5

[…] Source link […]

Great story!

1

What a great story/history of the USS New Orleans. Being a Baby-Boomer born in NO in September 1948, having lived in NO my whole life, & being an assiduous, long-time student of war history, I appreciate this USS NO story so very much. Thanks, Richard Cuccia