Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Historic Events of Colonial Days, by Rupert S. Holland (published 1916).

The island of Manhattan, which is now tightly packed with the office-buildings and houses of New York, was in 1661 the home of a small number of families who had come across the Atlantic Ocean from the Netherlands to settle this part of the new world for the Dutch West India Company. There was a fort at the southern end of the island, sometimes known as the Battery, and two roads led from it toward the north. One of these roads followed the line of the street now called Broadway, running north to a great open field, or common, and, skirting that, leading on to the settlement of Harlaem. In time this road came to be known as the Old Post Road to Boston. Another road ran to the east, and in its neighborhood were the farms of many of the richer Dutch settlers. Near where Third Avenue and Thirteenth Street now meet was the bouwery, as the Dutchmen called a farm, of Peter Stuyvesant, the governor of the colony of New Netherland. It was a large, prosperous bouwery, with a good-sized house for the governor and his family.

This Dutch governor, sturdy, impetuous, obstinate, had lost a leg while leading an attack on the Portuguese island of Saint Martin, in 1644, and now used a wooden stump, which caused him to be nicknamed “Wooden-Legged Peter.” He was a much better governor than the others who had been sent out by the West India Company to rule New Netherland. He had plenty of courage, but he had also a very determined will of his own, which often made him seem a tyrant to the other settlers.

Now there were two distinct classes of people in New Netherland: the peasants who worked the land, and the landowners, called patroons, who had bought vast tracts from the West India Company, and lived on them like European nobles. It was the patroons who brought the peasants over, paying for their passage, and the peasants worked for them until they could repay the amount of their passage money, and then took up small farms on their patroon’s estate, paying the rental in crops, as tenants did to the feudal lords of Europe. The great manors stretched north from the little town of New Amsterdam at the point of Manhattan Island. Above Peter Stuyvesant’s bouwery was the manor of the Kip family, called Kip’s Bay. In the middle of the island lived the Patroon De Lancey. Opposite, on Long Island, was the estate of the Laurences. And along the Hudson were the homes of the powerful families of Van Courtland and of Phillipse, of Van Rensselaer and of Schuyler. In spite of constant danger from Indians and their great distance from Europe the patroons lived in a certain magnificence, and grew in power down to the time of the Revolution. Farming and fur-trading were the chief sources of profit of the colony. There were a few storekeepers and mechanics, but they lived close to the fort and stockade at the Battery. The trades that had done so much to make the Netherlands in Europe rich played small part in the life of this New Netherland.

In the year 1661 the West India Company bought Staten Island from its patroon owner, a man named Cornelius Melyn. A block-house was built which was armed with two cannon and defended by ten soldiers, and invited the people of Europe who were called Waldenses and the Huguenots of France to settle on the island. Fourteen families soon came and took up farms there south of the Narrows. The West India Company, however, had broader views on religion than their governor, Peter Stuyvesant, had. John Brown, an Englishman, moved from Boston to Flushing, on Long Island, and, having by chance attended a Quaker meeting, invited the Quakers to meet at his new house. Neighbors told the governor that John Brown was using his farm as a meeting-place for Quakers, and Stuyvesant had him arrested. The quiet, unoffending farmer was fined twenty-five pounds and threatened with banishment, and when he failed to pay, was imprisoned in New Amsterdam for three months. Then Governor Stuyvesant issued an order banishing Farmer Brown. “John Brown,” so ran the order, “is to be transported from this province in the first ship ready to sail, as an example to others.” Soon afterward he was sent to Holland in the Gilded Fox, but the officers of the West India Company received him kindly, rebuked the haughty governor for his severity, and persuaded John Brown to return to Flushing. When he did go back Stuyvesant showed by his acts that he was ashamed of what he had done. For the governor, in spite of his headstrong acts, had sense enough to know that his little colony needed all the settlers it could find, no matter what their religion, and that Quakers made as trustworthy settlers as any other kind.

Early in 1663 an earthquake shook New Netherland and the country round it. Soon afterward the melting snows and very heavy rains caused a tremendous freshet, which covered the meadow lands along the rivers, and ruined all the crops. Then came an outbreak of smallpox, which spread among the Dutchmen and the Indians like fire in a field of wheat. Over a thousand of the Iroquois tribe died of the plague. Then, as if these troubles were not sufficient for the colony, Peter Stuyvesant soon heard that there was new danger of an Indian uprising against his people.

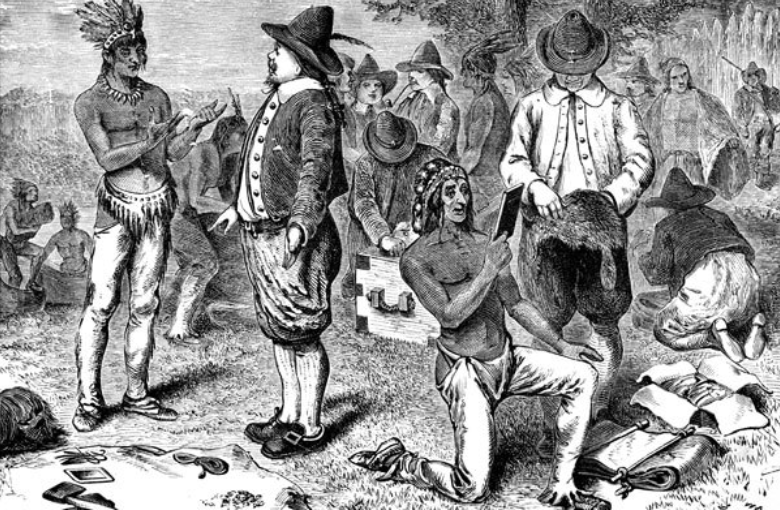

There had been a truce between the red men and the white, but the former could not forget that after their last attack on the Dutch fifteen of their warriors had been sent as slaves to the island of Curaçoa. There were many Indians near the prosperous settlement of Esopus, up in the Hudson country, and in the spring of 1663 settlers there sent word to the governor that they needed more protection from their dark-skinned neighbors. Stuyvesant replied that he would come himself soon and try to settle any differences. The Indian chiefs heard of this reply of the governor and in their turn sent him word that if he were coming to renew their treaty of friendship they should expect him to come without arms, and would then gladly meet in a council in the field outside the gate of Esopus, and smoke the pipe of peace with him.

This was a friendly message, and the settlers at Esopus who lived within the palisades, as well as those at the little village of Wildwyck, which had sprung up a short distance from the fort, decided they had been wrong in suspecting the Indians of intending to harm them, and went on with their farming as usual. Peter Stuyvesant, busy in New Amsterdam, had not yet had a chance to go up to Esopus. On the seventh of June, as on other days, Indians came into the village, chatted with the settlers, and sold corn and other provisions they had grown.

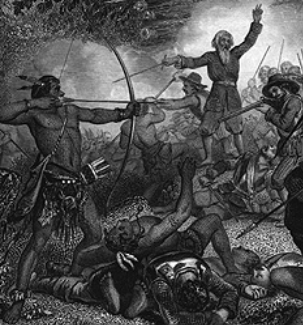

Then suddenly a war-whoop rang out inside the palisades, and was instantly followed by a hundred more within and without the gates. Indian blankets were thrown aside, and tomahawks and long knives gleamed in the hands of the savages. The settlers were taken completely by surprise. Each Indian had marked his man. Men, women, and children were made prisoners or killed. Houses were plundered and set on fire, and the flames, escaping to the farms, soon made havoc of the prosperous village.

The settlers fought, and for several hours the savage war-whoops were answered by the fire of muskets. The chief officer of the village, called the Schout, Roelof Swartwout by name, rallied a few men around him, and by desperate fighting at last drove the Indians outside the palisades and shut the gates against them. But the outer village was in ashes, the fields were strewn with bodies, and houses smoked to the sky. Within the palisades matters were not quite so bad, for a change of the wind had saved part of the buildings from the flames.

Twenty-one settlers had been killed, nine were badly wounded, and forty-five, most of them women and children, had been taken captive. All that night the Schout and his men stayed on guard at the gates, while in the distance they heard the shouts of the triumphant red men.

The news of what had happened at Esopus spread rapidly through the Hudson country. In the villages the men hurried to strengthen their palisades, farmers fled with their families to the shelter of the nearest forts. The news came to Governor Stuyvesant on Manhattan Island, and he instantly sent forty-two soldiers to Esopus, and offered rewards to all who would enlist. Some friendly Indians from Long Island joined his forces, scouts were sent through the woods to find the hostile Indians’ hiding-places. The Mohawks tried to make peace, and capturing some of the Dutch prisoners, sent them back to the village. The Mohawks also sent word that the Indians who had gone on the war-path felt they were only taking a just revenge for the act of the Dutch in sending some of their chiefs to Curaçoa, that they would return their other prisoners in exchange for rich presents, and were ready to make a new peace with the settlers.

But Peter Stuyvesant thought it needful to teach his Indian neighbors a lesson.

A white woman, Mrs. Van Imbrock, escaped from her captors, and finally reached Esopus after many hardships. She brought word that the Indians, some two hundred, had built a strong fort, and sent their prisoners every night under guard to a distant place in the mountains, intending to keep them as hostages. When he had heard her account, Stuyvesant sent out a party of two hundred and ten men, under Captain Crygier, armed with two small cannon, with which they hoped to make a breach in the walls of the Indian fort, which were only bulletproof.

This little army set out on the afternoon of July 26th. They made their way through forests, over high hills, and across rivers. They bivouacked for the night, and next morning marched on until they were about six miles from the fort. Half the men were sent on to make a surprise-attack, while the rest followed in reserve.

Scouts had brought word to the fort of the approach of the Dutch, and the Indians had gone into the mountains with their prisoners. So Captain Crygier’s men went into the fort and spent the night there, finding it an unusually well-built and well-protected place. An Indian woman, not knowing the white men were there, came back for some provisions, was taken prisoner, and told the direction in which the chiefs had gone. Next morning twenty-five men were left at the fort, and the others followed the trail to a mountain, where the squaw said the Indians meant to camp. There were no red men there, and the squaw told of another camp yet farther on.

The Dutch soldiers marched all day, but their hunt proved fruitless. Finally Captain Crygier gave the order to return to the captured fort. Here they burned the buildings, and carried off all the provisions. Then they returned to Esopus, to await other news.

Early in September word came that the Indians had built another fort, or castle, as they called it, thirty-six miles to the southwest. Again Captain Crygier set out with his men, and on the second day came in view of the fort. It stood on a height, and was built of two rows of stout palisades, fifteen feet high. Crygier divided his forces, and one-half the men crept toward the fort. Then a squaw saw them, and by her cry warned the Indians. Both parties of the Dutch rushed up the hill, stormed the palisades, drove their enemies before them, and scattered them in the fields. Behind the fort was a creek. The Indians waded and swam it, and made a stand on the opposite bank. But the fire of the Dutchmen was too much for them, and shortly they were flying wildly into the wilderness.

The Indian chief, Papoquanchen, and fourteen of his warriors were killed in the battle, twenty-two white prisoners were rescued, and fourteen Indians were captured. The fort was plundered of provisions, and the Dutch found eighty guns, besides, as they reported, “bearskins, deerskins, blankets, elk hides and peltries sufficient to load a shallop.”

There was great joy at Esopus when the victorious little army returned. Danger from that particular tribe of Indians seemed at an end, but to make the matter certain a third expedition was sent out in the fall. They scouted through the near-by country, but found only a few scattered red men. Those that were left of the Esopus tribe after that last attack on their fort had fled south and finally become part of the Minnisincks.

Again peace reigned in the Dutch settlements; the farmers went back to their fields, and the soldiers returned to the capital at New Amsterdam.

To the north of the Dutch colony lay the English colonies of New England, and the boundary between New Netherland and its neighbors had never been fixed. Many Englishmen had settled along the Hudson and on Long Island, and Governor Stuyvesant thought it was high time to reach some agreement with the New England governors. So he went to Boston in September, 1663; but scarcely had he left New Amsterdam when an English agent, James Christie, arrived on Long Island, and told the people of Gravesend, Flushing, Hempstead and Jamaica that they were no longer under Dutch rule, but that their territory had been annexed to the colony of Connecticut.

Now many of the settlers at Gravesend were English, and most of the magistrates and officers. When Christie read his announcement to the people one of the few faithful Dutch magistrates, Sheriff Stillwell, arrested him on a charge of treason. Then the other magistrates ordered the arrest of Stillwell in turn, and the public feeling against the latter was so strong that he had to send word secretly to New Amsterdam, asking for help. A sergeant and eight soldiers were sent from New Amsterdam, and they again arrested Christie and placed him under guard in Sheriff Stillwell’s house.

Rumors came that the farmers meant to rescue Christie, so he was taken at night to the fort on Manhattan Island. Sheriff Stillwell had to fly from his own house to escape the neighbors, and hurried to New Amsterdam, where he complained of the illegal acts of the Gravesend settlers. Excitement ran high. People on Long Island demanded that Christie be set free; but the Dutch council insisted on keeping him a prisoner. The council sent an express messenger to Peter Stuyvesant in Boston, asking him to settle the Long Island difficulties with the English governor there.

But the officers of New England would not agree to the sturdy Dutchman’s terms. And other English colonists went through the land that belonged to the Dutch, rousing the farmers against the West India Company. Richard Panton, armed with sword and pistol, threatened the men of Flatbush and other villages near by with the pillage of their property unless they would swear allegiance to the government at Hartford and fight against the Dutch. Such was the news that greeted Stuyvesant when he came back to his capital from Boston. He knew that there were not enough of the Dutch to resist an attack from the English, who had come swarming in great numbers recently into Massachusetts and Connecticut. His only hope lay in argument, and so he sent four of his leading men to Hartford to try to arrange a peaceful settlement.

The four Dutchmen sailed from New Amsterdam, and after two days on the water landed at Milford. There they took horses and rode to New Haven, where they spent the night. Next day they went on to Hartford over the rough roads of the wilderness. They were well received, and John Winthrop, who was governor of Connecticut and a son of Governor Winthrop of Massachusetts, admitted that some of the claims of the Dutch were just. But the rest of the officers at Hartford stoutly insisted that all that part of the Atlantic seacoast belonged to the king of England, by right of first discovery and claim. “The opinion of the governor,” said these men, “is but the opinion of one man. The grant of the king of England includes all the land south of the Boston line to Virginia and to the Pacific Ocean. We do not know any New Netherland, unless you can show a patent for it from the king of England.” Apparently the Dutch had no rights there at all; the whole tract between Massachusetts and Virginia belonged to Connecticut.

Still the Dutchmen tried to reach some sort of friendly agreement. They proposed that what was known as Westchester, the land lying north of Manhattan Island, should be considered part of Connecticut, but that the towns on Long Island should remain under the government of New Netherland. “We do not know of any province of New Netherland,” the Hartford officers replied. “There is a Dutch governor over a Dutch plantation on the island of Manhattan. Long Island is included in our patent, and we shall possess and maintain it.”

So the four Dutchmen had to return to Governor Stuyvesant with word that the Connecticut men would yield none of their claims.

The state of affairs was going from bad to worse. Stuyvesant called a meeting of men from all the neighboring villages, and the meeting sent a report to the Dutch government in Europe.

The report had hardly been sent, however, when more startling events took place in the colony. Two Englishmen, Anthony Waters and John Coe, with a force of almost one hundred armed men, visited many of the villages where there were English settlers, and told them they must no longer pay taxes to the Dutch, as their country belonged to the king of England. They put their own officers in place of the Dutch officers in these villages, and then, marching to settlements where most of the people were Dutch, they tried to make the people there take the oath of allegiance to the English king.

A month later a party of twenty Englishmen secretly sailed up the Raritan River in a sloop, called the chiefs of some of the neighboring Indian tribes together, and tried to buy a large tract of land from them. They knew all the while that the Dutch West India Company had bought that same land from the Indians some time before.

As soon as he heard of this Peter Stuyvesant sent Crygier, with some well-armed men, in a swift yacht, to thwart the English traders. He also sent a friendly Indian to warn the chiefs against trying to sell land they no longer owned. The Dutch yacht arrived in time to stop the Indians from dealing with the English, and the latter, baffled there, sailed their sloop down the bay to a place between Rensselaer’s Hook and Sandy Hook, where they met other Indians and tried to bargain with them for land. The Dutch Crygier overtook them.

“You are traitors!” he cried. “You are acting against the government to which you have taken the oath of fidelity!”

“This whole country,” answered the men from the sloop, “has been given to the English by His Majesty the King of England.”

Then the two parties separated, Crygier and his men sailing back to New Amsterdam.

While matters stood this way in the province of New Netherland an Englishman, John Scott, petitioned King Charles the Second to grant him the government of Long Island, which he said the Dutch settlers were unjustly trying to take away from the king of England. Scott was given authority to make a report to the English government on the state of affairs in that part of the New World, and in order to do this he sailed to America and went to New Haven, where he was warmly welcomed. The colony of Connecticut gave him the powers of a magistrate throughout Long Island, and he at once set to work to wrest the island from the Dutch, whom he upbraided as “cruel and rapacious neighbors who were enslaving the English settlers.”

Some of the villages on Long Island, however, and especially those where there were many Quakers and Baptists, did not want to come under the rule of the Puritans. Therefore six towns, Hempstead, Gravesend, Flushing, Middlebury, Jamaica and Oyster Bay, formed a government of their own, asking John Scott to act as their president, until the king of England should establish a permanent government for them. Scott swelled with pride in his new power. He gathered an armed force of one hundred and seventy men, horse and foot, and marched out to compel the neighboring Dutch towns to join his new colony.

First he marched on Brooklyn. There he told the citizens that their land belonged to the crown of England, and that he now claimed it for the king. He had so many men with him that the Dutch saw it would be impossible to arrest him, but one of them, the secretary, Van Ruyven, suggested that he should cross the river to New Amsterdam and talk with Peter Stuyvesant. Scott pompously answered, “Let Stuyvesant come here with a hundred men; I will wait for him and run my sword through his body!” And he scowled and marched up and down before the stolid Dutchman like a fierce cock-o’-the-walk.

The Dutchmen of Brooklyn, however, did not seem anxious to exchange the rule of Governor Peter Stuyvesant for that of Captain John Scott. As he was strutting up and down Captain Scott spied a boy who looked as if he would like to use his fists on the Englishman. The boy happened to be a son of Governor Stuyvesant’s faithful officer Crygier. Captain Scott walked up to the boy, and ordered him to take off his hat and salute the flag of England. Young Crygier refused, and the quick-tempered captain struck at him. One of the men standing by called out, “If you have blows to give, you should strike men, not boys!”

Four of Scott’s men jumped at the man who had dared to speak so, and the latter, picking up an axe, tried to defend himself, but soon found it best to run. Scott ordered the people of Brooklyn to give the man up, threatening to burn the town unless they did so. But the man was not surrendered, and the captain did not dare to carry out his threat.

Instead he marched to Flatbush, and unfurled his flag before the house of the sheriff. Settlers gathered round to see what was happening, and Captain Scott made them a speech. “This land,” said he to the Dutchmen, “which you now occupy, belongs to His Majesty, King Charles. He is the right and lawful lord of all America, from Virginia to Boston. Under his government you will enjoy more freedom than you ever before possessed. Hereafter you shall pay no more taxes to the Dutch government, neither shall you obey Peter Stuyvesant. He is no longer your governor, and you are not to acknowledge his authority. If you refuse to submit to the king of England, you know what to expect.”

But the men of Flatbush were no more ready to obey the haughty captain than those of Brooklyn had been. One of the magistrates dared to tell Scott that he ought to settle this dispute with Peter Stuyvesant. “Stuyvesant is governor no longer,” he retorted. “I will soon go to New Amsterdam, with a hundred men, and proclaim the supremacy of His Majesty, King Charles, beneath the very walls of the fort!”

The Dutch would not obey him, but neither would they take up arms against him. Such treatment angered the fire-eating captain more and more. He marched his troop to New Utrecht, where the Dutch flag floated over the block fort, armed with cannon. Meeting no resistance from the peace-loving settlers Scott hauled down their flag and replaced it with the flag of England. Then, using the Dutch cannon and Dutch powder he fired a salute to announce his victory. All those who passed the fort were ordered to take off their hats and bow before the new banner, and those who refused were arrested by his men, and some were bound and beaten.

Peter Stuyvesant, in New Amsterdam, heard of these disturbances on Long Island, and sent three of his leading men to meet Scott and try to make some settlement with him. They met the captain at Jamaica, and after much wrangling, at last reached what they thought might be an agreement. But as they left Scott fired these words at their backs: “This whole island belongs to the king of England. He has made a grant of it to his brother, the Duke of York. He knows that it will yield him an annual revenue of one hundred and fifty thousand dollars. He is soon coming with an ample force, to take possession of his property. If it is not surrendered peaceably he is determined to take, not only the whole island, but also the whole province of New Netherland!”

This was alarming news. Some of the English settlers were rallying to Scott’s command, the Dutch in some of the villages fled to Dutch forts for shelter. Even the prosperous men in New Amsterdam began to fear lest the English captain should attack their homes. Fortifications were hurriedly built, and men enrolled as soldiers.

Peter Stuyvesant, fearful lest he should lose his colony, knowing well that the English greatly outnumbered the Dutch, found himself in a very difficult situation. But “Wooden-Legged Peter” was a fighter, quite as fiery as John Scott when his blood was up.