Editor’s note: Here follow Chapters 27 through 32 of My Reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, by General Ben Viljoen (published 1902). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XXVII

THE SECOND CHRISTMAS AT WAR.

The veldt was in splendid condition at the foot of Bothasberg, where we had pitched our camp. We found mealies and cattle left everywhere. The enemy did not know where we really were, and could not, therefore, bother us for the time being. Our Government was at Tautesberg, about 12 miles north of Bothasberg, and we received a visit from Acting-President Burger, who brought with him the latest news from Europe, and the reports from the other commandos. Mr. Burger said he was sorry we had to leave the Pretoria district, but he could understand our horses would have all been killed by the sickness if we had stopped at Poortjesnek. As regards the Battle of Rhenosterkop, he expressed the Government’s satisfaction with the result.

On the 16th of December we celebrated Dingaan’s Day in a solemn manner. Pastor J. Louw, who had faithfully accompanied us during these fatiguing months of retreats and adversity, delivered a most impressive address, describing our position. Several officers also spoke, and I myself had a go at it, although I kept to politics. In the afternoon the burghers had sports, consisting of races on foot and on horseback. The prizes were got together by means of small contributions from the officers. All went well, without any mishaps, and it was unanimously voted to have been very entertaining.

It was a peculiar sight—taking into consideration the circumstances—to see these people on the “veldt” feasting and of good cheer, each trying to amuse the other, under the fluttering “Vierkleur”—the only one we possessed—but the look of which gladdened the hearts of many assisting at this celebration in the wilderness. How could we have been in a truly festive mood without the sight of that beloved banner, which it had cost so many sacrifices to protect, and to save which so much Afrikander blood had been shed.

And in many of us the thought suggested itself: “O, Vierkleur of our Transvaal, how much longer shall we be allowed to see you unfurled? How long, O Lord, will a stream of tears and blood have to flow before we are again the undisputed masters of our little Republic, scarcely visible on the world’s map? For how long will our adored Vierkleur be allowed to remain floating over the heads of our persecuted nation, whose blood has stained and soaked your colours for some generations? We hope and trust that so sure as the sun shall rise in the east and set in the west, so surely may this our flag, now wrapped in sorry mourning, soon flutter aloft again in all its glory, over the country on which Nature lavishes her most wondrous treasures.”

The Afrikander character may be called peculiar in many respects. In moments of reverse, when the future seems dark, one can easily trace its pessimistic tendencies. But once his comrades buried, the wounded attended to, and a moment’s rest left him by the enemy, the cheerful part of the Boer nature prevails, and he is full of fun and sport. If anybody, in a sermon or in a speech, try to impress on him the seriousness of the situation, pointing out how our ancestors have suffered and how we have to follow in their steps, our hero of yesterday, the jolly lad who was laughing boisterously and joking a minute ago, is seen to melt, and the tears start in his eyes. I am now referring to the true Afrikander. Of course, there are many calling themselves Afrikanders who during this War have proved themselves to be the scum of the nation. I wish to keep them distinguished from the true, from the noble men belonging to this nationality of whom I shall be proud as long as I live, no matter what the result of the War may be.

Our laagers were not in a very satisfactory position, more as regards our safety than the question of health, sickness being expected to make itself felt only later in the year.

We therefore decided to “trek” another 10 miles, to the east of Witpoort, through Korfsnek, to the Steenkampsbergen, in order to pitch or camp at Windhoek. Windhoek (wind-corner) was an appropriate name, the breezes blowing there at times with unrelenting fury.

Here we celebrated Christmas of 1900, but we sorely missed the many presents our friends and lady acquaintances sent us from Johannesburg on the previous festival, and which had made last year’s Christmas on the Tugela such a success.

No flour, sugar or coffee, no spirits or cigars to brighten up our festive board. This sort of thing belonged to the luxuries which had long ceased to come our way, and we had to look pleasant on mealie-porridge and meat, varied by meat and mealie-porridge.

Yet many groups of burghers were seen to be amusing themselves at all sorts of games; or you found a pastor leading divine service and exhorting the burghers. Thus we kept our second Christmas in the field.

About this time the commandos from the Lydenburg district (where we now were) as well as those from the northern part of Middelburg, were placed under my command, and I was occupied for several days in reorganising the new arrivals. The fact of the railway being almost incessantly in the hands of the enemy, and the road from Machadodorp to Lydenburg also blocked by them (the latter being occupied in several places by large or small garrisons) compelled us to place a great number of outposts to guard against continual attacks and to report whenever some of the columns, which were always moving about, were approaching.

The spot where our laagers were now situated was only 13 miles from Belfast and Bergendal, between which two places General Smith-Dorrien’s strong force was posted; while a little distance behind Lydenburg was General Walter Kitchener with an equally strong garrison. We were, therefore, obliged to be continually on the alert, not relaxing our watchfulness for one single moment. One or two burghers were still deserting from time to time, aggravating their shameful behaviour by informing the enemy of our movements, which often caused a well-arranged plan to fail. We knew this was simply owing to these very dangerous traitors.

The State Artillerymen, who had now been deprived of their guns, were transformed into a mounted corps of 85 men, under Majors Wolmarans and Pretorius, and placed under my command for the time being.

It was now time we should assume the offensive, before the enemy attacked us. I therefore went out scouting for some days, with several of my officers, in order to ascertain the enemy’s positions and to find out their weakest spot. My task was getting too arduous, and I decided to promote Commandant Muller to the rank of a fighting-general. He turned out to be an active and reliable assistant.

CHAPTER XXVIII

CAPTURE OF “LADY ROBERTS.”

After I had carefully reconnoitred the enemy’s positions, I resolved, after consulting my fighting-general, Muller, to attack the Helvetia garrison, one of the enemy’s fortifications or camps between Lydenburg and Machadodorp. Those fortifications served to protect the railway road from Machadodorp Station to Lydenburg, along which their convoys went twice a week to provision Lydenburg village. Helvetia is situated three miles east of Machadodorp, four miles west of Watervalboven Station, where a garrison was stationed, and about three miles south of a camp near Zwartkoppies. It was only protected on the north side. Although it was difficult to approach this side on account of a mountainous rand through which the Crocodile River runs, yet this was the only road to take. It led across Witrand or Bakenkop; the commandos were therefore obliged to follow it, and had to do this at night time, for if they had passed the Bakenkop by day they would have exposed themselves to the enemy’s artillery fire from the Machadodorp and Zwartkoppies garrisons.

During the night of the 28th of December 1900, we marched from Windhoek, past Dullstroom, up to the neighbourhood of Bakenkop, where we halted and divided the commandos for the attack, which was to be made in about the following order:—

Fighting-General Muller was to trek with 150 men along the convoy-road between Helvetia and Zwartkoppies up to Watervalboven, keeping his movements concealed from the adversary. Commandant W. Viljoen (my brother), would approach the northerly and southerly parts of Helvetia within a few hundred paces, with part of the Johannesburgers and Johannesburg Police. This commando numbered 200 men.

In order to be able to storm the different forts almost simultaneously we were all to move at 3.30 a.m., and I gave the men a password, in order to prevent confusion and the possibility of our hitting one another in the general charge. There being several forts and trenches to take the burghers were to shout “Hurrah!” as loudly as they could in taking each fort, which would show us it was captured, and at the same time encourage the others. Two of our most valiant field-cornets, P. Myburgh and J. Cevonia, an Italian Afrikander, were sent to the left, past Helvetia, with 120 men, to attack Zwartkoppies the moment we were to storm Helvetia, while I kept in reserve the State Artillerists and a field-cornet’s posse of Lydenburgers to the right of the latter place, near Machadodorp, which would enable me to stop any reinforcements sent to the other side from that place or from Belfast. For if the British were to send any cavalry from there they would be able to turn our rear, and by marching up as soon as they heard the first report of firing at Helvetia, they would be in a position to cut me up with the whole of my commando. I only suggest the possibility of it, and cannot make out why it was not attempted. I can only be thankful to the British officers for omitting to do this.

I had taken up a position, with some of my adjutants, between the commandos as arranged, and stood waiting, watch in hand, for the moment the first shot should be fired. My men all knew their places and their duties, but unfortunately a heavy fog rose at about 2 o’clock, which made the two field-cornets who were to attack the Zwartkoppies lose their way and the chance of reaching their destination before daybreak.

I received the news of this failure at 3.20, i.e., ten minutes before the appointed time of action. A bad beginning, I thought, and these last ten minutes seemed many hours to me.

I struck a match every moment, under cover of my macintosh, to see if it were yet half past three. Another minute and it would soon be decided whether I should be the vanquished or the victor. How many burghers, who were now marching so eagerly to charge the enemy in his trenches, would be missed from our ranks to-morrow? It is these moments of tension which make an officer’s hair turn grey. The relation between our burgher and his officers is so entirely different from that which exists between the British officer and his men or between these ranks perhaps in any other standing army. We are all friends. The life of each individual burgher in our army is highly valued by his officer and is only sacrificed at the very highest price. We regret the loss of a simple burgher as much as that of the highest in rank. And it was the distress and worry of seeing these lives lost, which made me ponder before the battle.

Suddenly one of my adjutants called out: “I hear some shouting. What may this be?”

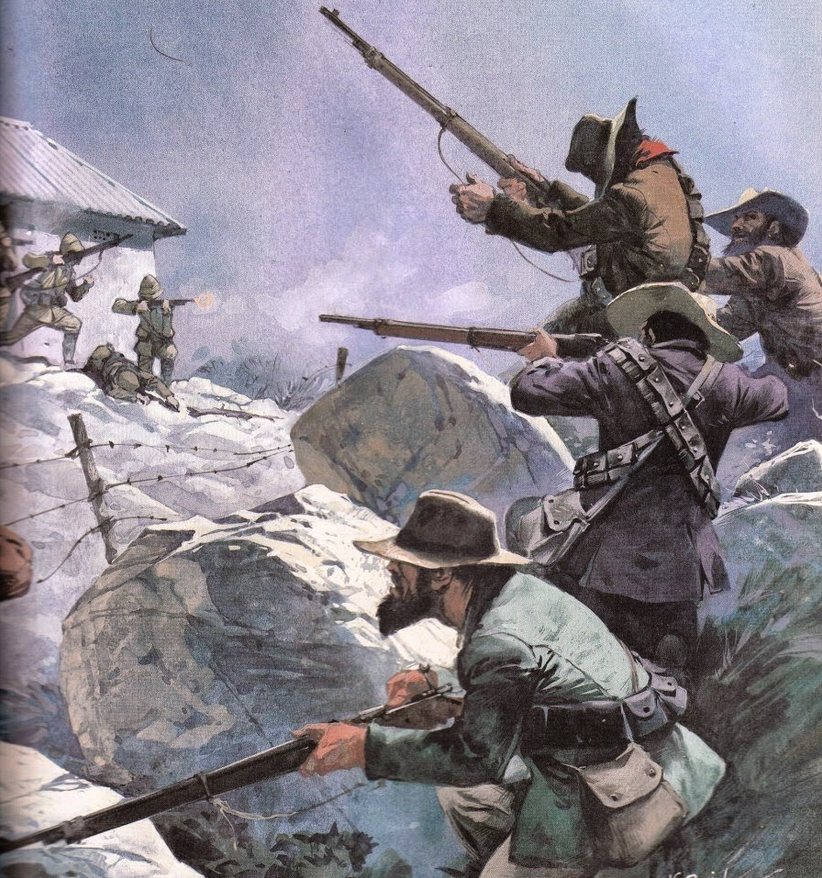

I threw my waterproof over my head and struck a match, then cried: “It is time, my lads!” And in a few seconds a chain of fire flamed up round the forts, immediately followed by the rattling and crackling of the burghers’ Mausers. The enemy was not slow in returning our fire.

It is not easy to adequately render the impression a battle in the dark makes. Each time a shot is fired you see a flash of fire several yards long, and where about 500 or 600 rifles are being fired at a short distance from you, it makes one think of a gigantic display of fireworks.

Although it was still dusk, I could easily follow the course of the fight. The defenders’ firing slackened in several places, to subside entirely in others, while from the direction of the other reports and flashes, our men were obviously closing up, drawing tighter the ring round the enemy.

So far, according to my scouts, no stir had been made from Belfast, which encouraged me to inform the officers that we were not being cut off. At daybreak only a few shots were falling, and when the fog cleared up I found Helvetia to be in our hands.

General Muller reported that his part of the attack had been successfully accomplished, and that a 4.7 naval gun had been found in the great fortress. I gave orders to fetch this gun out of the fort without delay, to take away the prisoners we had made and as much of the commissariat as we could manage to carry, and to burn the remainder.

Towards the evening we were fired at by two guns at Zwartkoppies, making it very difficult for us to get the provisions away.

A great quantity of rum and other spirits was found among the enemy’s commissariat, and as soon as the British soldiers made prisoners were disarmed, they ran up to it, filled their flasks, and drank so freely that about thirty of them were soon unable to walk. Their bad example was followed by several burghers, and many a man who had not been given to drinking used this opportunity to imbibe a good quantity, making it very difficult for us to keep things in order.

About 60 men of the garrison had been killed or wounded, and their commanding officer had received some injuries, but fortunately there was a doctor there who at once attended to these cases. On our side we had five men killed and seven wounded—the brave Lieutenant Nortje and Corporal J. Coetzee being amongst them.

A small fort, situated between the others, had been overlooked, through a misunderstanding, and a score of soldiers who were garrisoning it had been forgotten and omitted to be disarmed.

An undisciplined commando is not easily managed at times. It takes all the officers’ tact and shrewdness to get all the captured goods—like arms, ammunition, provisions, &c.—transported, especially when drink is found in a captured camp.

When we discussed the victory afterwards, it became quite clear that our tactics in storming the enemy’s positions on the east and south sides had been pregnant of excellent results, for the English were not at all prepared at these points, though they had been on their guard to the north. In fact it had been very trying work to force them to surrender there. The officer in command, who was subsequently discharged from the British Army, had done his best, but he was wounded in the head at the beginning of the fight, and so far as I could ascertain there had been nobody to take his place. Three lieutenants were surprised in their beds and made prisoners-of-war. In the big fort where we found the naval gun, a captain of the garrison’s artillery was in command. This fortress had been stormed, as already stated, from the side on which the attack had not been expected and the captain had not had an opportunity of firing many shots from his revolver, when he was wounded in the arm and compelled to surrender to the burghers who rushed up. Two hundred and fifty prisoners, including four officers, were made, the majority belonging to the Liverpool regiment and the 18th regiment of Hussars. They were all taken to our laager.

We succeeded in bringing away the captured gun in perfect order, also some waggons. Unfortunately the cart with the projectiles or shell, stuck in the morass and had to be left behind.

I gave orders to have a gun which we had left with the reserve burghers at Bakenkop, brought up, to open fire on the two pieces which were firing at us from Zwartkoppies, and to cover our movements while we were taking away the prisoners-of-war and the captured stores. I was in hopes of getting an opportunity of releasing the carts which stuck. But Fate was against us. A heavy hailstorm accompanied by thunder and lightning, fiercer than I have ever witnessed in South Africa before, broke over our heads. Several times the lightning struck the ground around us, and the weather became so alarming that the drunken “Tommies” began to talk about their souls, and further efforts to save the carts had to be abandoned.

Whoever may have been the officer in command at Zwartkoppies he really deserved a D.S.O., which he obtained, too.

What that order really means I wot not, but I know that an English soldier is quite prepared to risk his life to deserve one, and as the decoration itself cannot be very expensive, it pays the British Government to be very liberal with it. A Boer would be satisfied with nothing less than promotion as a reward for heroism.

When the storm subsided we went on. It was a remarkable sight—a long procession of “Tommies,” burghers, carts, and the naval gun, 18 feet long, an elephantine one when compared with our small guns.

It struck me again on this occasion what little bad feeling there was really between Boer and Briton, and how they both fight simply to do their duty as soldiers. As I rode along the stream of men I noticed several groups of burghers and soldiers sitting together along the road, eating from one tin of jam and dividing their loaf between them, and drinking out of the same field flask.

I remember some snatches of conversation I overheard:—

Tommy: By Jove, but you fellows gave us jip. If you had come a little later you wouldn’t have got us so easy, you know.

Burgher: Never mind, Tommy, we got you. I suppose next time you will get us. Fortunes of war, you know. Have some more, old boy. Oh, I say, here is the general coming.

Tommy: Who’s he? Du Wyte or Viljohn?

And then as I passed them the whole group would salute very civilly.

We stopped at Dullstroom that night, where we found some lodgings for the captured British officers. We were sorry one of the Englishmen had not been given time to dress himself properly, for we had a very scanty stock of clothes, and it was difficult to find him some.

The next morning I found half a dozen prisoners-of-war had sustained slight flesh wounds during the fight, and I sent them on a trolley to Belfast with a dispatch to General Smith-Dorrien, informing him that four of his officers and 250 men were in our hands, that they would be well looked after, and that I now sent back the slightly wounded who had been taken away by mistake.

I will try to give the concluding sentence of my communication as far as I remember it, and also the reply to it. I may add that the words “The Lady Roberts” had been chiselled on the naval gun, and that many persons had just been expelled from Pretoria and other places as being considered “undesirables.”

My letter wound up as follows:—

“I have been obliged to expel “The Lady Roberts” from Helvetia, this lady being an “undesirable” inhabitant of that place. I am glad to inform you that she seems quite at home in her new surroundings, and pleased with the change of company.”

To which General Smith-Dorrien replied:

“As the lady you refer to is not accustomed to sleep in the open air, I would recommend you to try flannel next to the skin.”

I had been instructed to keep the officers we had taken prisoners until further orders, and these four were therefore lodged in an empty building near Roos Senekal under a guard. The Boers had christened this place “Ceylon,” but the officers dubbed it “the house beautiful” on account of its utter want of attractiveness.

They were allowed to write to their relatives and friends, to receive letters, and food and clothes, which were usually sent through our lines under the white flag. The company was soon augmented by the arrivals of many other British officers who were taken prisoners from time to time.

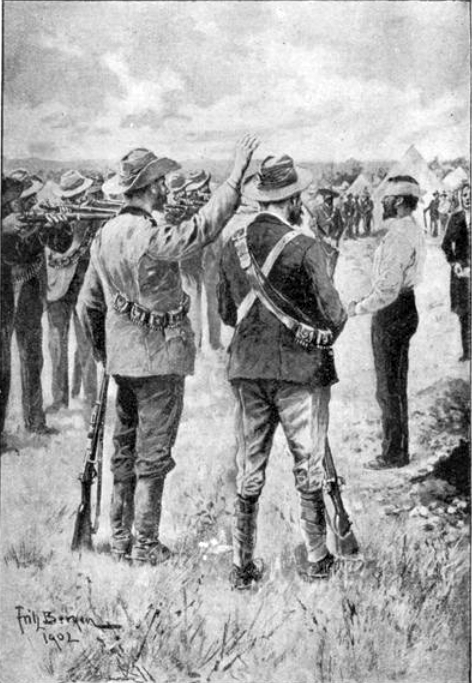

The 250 captured rank and file were given up to the British authorities at Middelburg some days after, for military reasons.

“The Lady Roberts” was the first and so far the last big gun taken from the English, and we are proud to say that never during this War, notwithstanding all our vicissitudes and reverses, have the British succeeded in taking one of our big guns.

One might call this bragging, but that is not my intention and I do not think I am given to boasting. We only relate it as one of the most remarkable incidents of the War, and as a fact which we may recall with satisfaction.

As already related, the cart with the shells for “The Lady Roberts” had to be left behind after the battle. Nothing would have given us greater pleasure than to send some shells from “Her Ladyship” into the Belfast camp on the last day of 1900, with the “Compliments of the Season.” Not of course, in order to cause any destruction, but simply as a New Year’s greeting. We would have sent them close by like the Americans in Mark Twain’s book: “Not right in it, you know, but close by or near it.” Only the shells were wanting, for with the gun were 50 charged “hulzen” and a case of cordite “schokbuizen.”

We tried to make a shell from an empty “Long Tom” one, by cutting the latter down, for the “Long Toms” shells were of greater calibre, and after having it filled with four pom-pom bullets, some cordite etc., we made it tight with copper wire, and soldered the whole together.

But when the shell was fired it burst a few steps away from the mouth of the cannon, and we had to abandon all hope of ever hearing a shout from the distinguished “Lady’s” throat.

It was stowed away safely in the neighbourhood of Tautesberg and guarded by a group of cattle-farmers, or rather “bush-lancers,” as they were afterwards called, in case we should get hold of the proper shells some day or other.

In connection with the attack on Helvetia I should like to quote the following lines, written by one of our poetasters, State-Secretary Mr. F. W. Reitz, in the field, although the translation will hardly give an adequate idea of the peculiar treatment of the subject:—

“Hurrah for General Muller, hurrah for Ben Viljoen, They went for ‘Lady Roberts’ and caught her very soon. They caught her at Helvetia, great was Helvetia’s fall! Come up and see ‘The Lady,’ you Ooms and Tantes all.

It was a Christmas present (they made a splendid haul), And sent ‘The Lady Roberts,’ a present to Oom Paul. It cheered the poor Bush-lancers, it cheered the ‘trek boers’ all, It made them gladly answer to freedom’s battle call.

Lord Roberts gave up fighting, he did not care a rap, But left his dear old ‘Lady,’ who’s fond of mealie-pap. Of our dear wives and children he burned the happy homes, He likes to worry Tantes but fears the sturdy Ooms.

But his old ‘Lady Roberts’ (the lyddite-spitting gun), He sent her to Helvetia to cheer the garrison; He thought she would be safe there, in old Smith-Dorrien’s care; To leave the kopjes’ shelter the Boers would never dare.

Well done, Johannesburgers, Boksburgers, and police, Don’t give them any quarter, don’t give them any peace; Before the sleepy “Tommies” could get their stockings on, The forts were stormed and taken, and all the burghers gone.

We took 300 soldiers, provisions, and their guns, And of their ammunition we captured many tons. ‘This is guerilla warfare,’ says Mr. Chamberlain, But those we have bowled over will never fight again.

Let Roberts of Kandahar, and Kitchener of Khartoum, Let Buller of Colenso make all their cannon boom. They may mow down the kaffirs, with shield and assegai, But on his trusty Mauser the burgher can rely.

For now the white man’s fighting, these heroes dare not stay, Lord Kitchener’s in Pretoria, the others ran away. Lord Roberts can’t beat burghers, although he Candahar, The Lords are at a distance, the Generals few and far!

They may annex and conquer, have conquered and annexed, Yet when the Mauser rattles the British are perplexed. Stand firm then, Afrikanders, prolong the glorious fight, Unfurl the good old ‘Vierkleur.’ Stand firm, for right is might!

What though the sky be clouded, what though the light be gone; The day will dawn to-morrow, the sun will shine anon; And though in evil moments a hero’s hand may fail, The strong will be confounded and right will yet prevail!”

CHAPTER XXIX

A DISMAL “HAPPY NEW YEAR.”

This is the 31st of December, 1900, two days after the victory gained by our burghers over the English troops at Helvetia, at the same time the last day of the year, or, as they call it, “New Year’s Eve”; which is celebrated in our country with great enjoyment. The members of each family used to meet on that day, sometimes coming from all parts of the country. If this could not be done they would invite their most intimate friends to come and see the Old Year out—to “ring out the old, and ring in the new,” for “Auld Lang Syne.” This was one of the most festive days for everybody in South Africa. On the 31st of December, 1899, we had had to give up our time-honoured custom, there being no chance of joining in the friendly gathering at home, most of us having been at the front since the beginning of October, 1899, while our commandos were still in the very centre of Natal or in the northern part of Cape Colony; Ladysmith, Kimberley, and Mafeking were still besieged, and on the 15th of December the great victory of Colenso over the English Army had been won.

It is true that even then we were far from our beloved friends, but those who had not been made prisoners were still in direct communication with those who were near and dear to them. And although we were unable to pass the great day in the family circle, yet we could send our best wishes by letter or by wire. We had then hoped it would be the last time we should have to spend the last day of the year under such distressing circumstances, trusting the war would soon be over.

Now 365 days had gone by—long, dreary, weary days of incessant struggle; and again our expectations had not been realised, and our hopes were deferred. We were not to have the privilege of celebrating “the Old and the New” with our people as we had so fervently wished the previous year on the Tugela.

The day would pass under far more depressing circumstances. In many homes the members of the family we left behind would be prevented from being in a festive mood, thinking as they were of the country’s position, while mourning the dead, and pre-occupied with the fate of the wounded, of those who were missing, or known to be prisoners-of-war.

It was night-time, and everybody was under the depression of the present serious situation. Is it necessary to say that we were all absorbed in our thoughts, reviewing the incidents of the past year? Need we say that everyone of us was thinking with sadness of our many defeats, of the misery suffered on the battlefields, of our dead and wounded and imprisoned comrades; how we had been compelled to give up Ladysmith, Kimberley, and Mafeking, and how the principal towns of our Republics, Bloemfontein and Pretoria, where our beloved flag had been flying for so many long years, over an independent people, were now in the hands of the enemy? Need we say we were thinking that night more than ever of our many relatives who had sacrificed their blood and treasure in this melancholy War for the good Cause; of our wives and children, who did not know what had become of us, and whom most of us had not seen for the last eight months. Were they still alive? Should we ever see them alive? Such were the terrible thoughts passing through our minds as we silently sat round the fires that evening.

Nor did anything tend to relieve the sombre monotony. This time we should not have a chance of receiving some little things to cheer us up and remind us that our dearest friends had thought of us. Our fare would that day be the eternal meat and mealies—mealies and meat.

But why call to mind all these sombre memories of the past? Sufficient unto the day it seems was the evil thereof. Why sum up the misery of a whole year’s struggles? And thus we “celebrated” New Year’s Eve of 1900, till we found our consolation in that greatest of blessings to a tired-out man—a refreshing sleep.

But no sooner had we risen next morning than the cheerful compliments: “A Happy New Year!” or “My best wishes for the New Year” rang in our ears. We were all obviously trying to lay stress on the possible blessings of the future, so as to make each other forget the past, but I am afraid we did not expect the fulfilment of half of what we wished.

For well we knew how bad things were all round, how many dark clouds were hanging over our heads, and how very few bright spots were visible on the political horizon.

CHAPTER XXX

GENERAL ATTACK ON BRITISH FORTS.

My presence was requested on the 3rd of January, 1901, by the Commandant-General at a Council of War, which was to be held two days after at Hoetspruit, some miles east of Middelburg. General Botha would be there with his staff, and a small escort would take him from Ermelo over the railway through the enemy’s lines. My commandos were to hold themselves in readiness. There was no doubt in my mind as to there being some great schemes on the cards, and that the next day we should have plenty to do, for the Commandant-General would not come all that way unless something important was on. And why should my commandos have to keep themselves in readiness?

On the morning of the 5th I went to the place of destination, which we reached at 11 o’clock, to find the Commandant-General and suite had already arrived. General Botha had been riding all night long in order to get through the enemy’s lines, and had been resting in the shadow of a tree at Hoetspruit. The meeting of his adjutants and mine was rather boisterous, and woke him up, whereupon he rose immediately and came up to me with his usual genial smile. We had often been together for many months in the War, and the relations between us had been very cordial. I therefore do not hesitate to call him a bosom-friend, with due respect to his Honour as my chief.

“Hullo, old brother, how are you?” was Botha’s welcome.

“Good morning, General, thank you, how are you?” I replied.

My high appreciation of, and respect for his position, made me refrain from calling him Louis, although we did not differ much in age, and were on intimate terms.

“I must congratulate you upon your successful attack on Helvetia. You made a nice job of it,” he said. “I hope you had a pleasant New Year’s Eve. But,” he went on, “I am sorry in one way, for the enemy will be on his guard now, and we may not succeed in the execution of the plans we are going to discuss to-day, and which concern those very districts.”

“I am sorry, General,” I replied, “but of course I know nothing of those plans.”

“Well,” rejoined the Commandant-General, “we will try anyhow, and hope for the best.”

An hour later we met in council. Louis Botha briefly explained how he had gone with General Christian Botha and Tobias Smuts, with 1,200 men, to Komatiboven, between Carolina and Belfast, where they had left the commandos to cross the line in order to meet the officers who were to the north of it with the object of going into the details of a combined attack on the enemy’s camps.

All were agreed and so it was decided that the attack would be made during the night of the 7th of January, at midnight, the enemy’s positions being stormed simultaneously.

The attack was to be made in the following way: The Commandant-General and General C. Botha along with F. Smuts, would attack on the southern side of the garrisons, in the following places: Pan Station, Wonderfontein Station, Belfast Camp and Station, Dalmanutha and Machadodorp, while I was to attack these places from the north. The commandos would be divided so as to have a field-cornet’s force charge at each place.

I must say that I had considerable difficulty in trying to make a little go a long way in dividing my small force along such a long line of camps, but the majority were in favour of this “frittering-away” policy, and so it had to be done.

The enemy’s strength in different places was not easy to ascertain. I knew the strongest garrison at Belfast numbered over 2,500 men, and this place was to be made the chief point of attack, although the Machadodorp garrison was pretty strong too. The distance along which the simultaneous attack was to be made was about 22 miles and there were at least seven points to be stormed, viz., Pan Station, Wonderfontein, Belfast Village, Monument Hill (near Belfast), the coal mines (near Belfast), Dalmanutha Station and Machadodorp. A big programme, no doubt.

I can only, of course, give a description of the incidents on my side of the railway line, for the blockhouses and the forts provided with guns, which had been built along the railway, separated us entirely from the commandos to the south. The communication between both sides of the railway could be only kept up at night time and with a great amount of trouble, by means of despatch-carriers. We, therefore, did not even know how the attacking-parties on the southern side had been distributed. All we knew was, that any place which was to be attacked from the north would also be stormed from the south at the same time, except the coal mine west of Belfast, occupied by Lieutenant Marshall with half a section of the Gloucester Regiment, which we were to attack separately, as it was situated some distance north of the railway line.

I arranged my plans as follows: Commandant Trichardt, with two field-cornets posses of Middelburgers and one of Germiston burghers, were to attack Pan and Wonderfontein; the State Artillery would go for the coal mine; the Lydenburgers look after Dalmanutha and Machadodorp; while General Muller with the Johannesburgers and Boksburgers would devote their attention to Monument Hill.

I should personally attack Belfast Village, with a detachment of police, passing between the coal mine and Monument Hill. My attack could only, of course, be commenced after that on the latter two places had turned out successfully, as otherwise I should most likely have my retreat cut off.

In the evening of the 7th of January all the commandos marched, for the enemy would have been able to see us from a distance on this flat ground if we had started in the daytime, and would have fired at us with their 4·7 guns, one of which we knew to be at Belfast. We had to cover a distance of 15 miles between dusk and midnight. There was therefore no time to be lost, for a commando moves very slowly at night time if there is any danger in front. If the danger comes from the rear, things very often move quicker than is good for the horses. Then the men have to be kept together, and the guides are followed up closely, for if any burghers were to lag behind and the chain be broken, 20 or 30 of them might stray which would deprive us of their services.

It was one of those nights, known in the Steenkamp Mountains as “dirty nights,” very dark, with a piercing easterly wind, which blew an incessant, fine, misty rain into our faces. About nine o’clock the mist changed into heavy rains, and we were soon drenched to the skin, for very few of us wore rainproof cloaks.

At ten the rain left off, but a thick fog prevented us from seeing anything in front of us, while the cold easterly wind had numbed our limbs, almost making them stiff. Some of the burghers had therefore to be taken up by the ambulance in order to have their circulation restored by means of some medicine or artificial treatment. The impenetrable darkness made it very difficult to get on, as we were obliged to keep contact by means of despatch-riders; for, as already stated, I had to wait with the police for the result of the attack on the two positions to the right and left of me.

Exactly at midnight all had arrived at the place of destination. Unfortunately the wind was roaring so loudly as to prevent any firing being heard even at a hundred paces distant.

The positions near Monument Hill and the coal mine were attacked simultaneously, but unfortunately our artillerymen could not distinctly see the trenches on account of the darkness, and they charged right past them, and had to turn back when they became aware of the fact, by which time the enemy had found out what was up, and allowed their assailants to come close up to them (it was a round fort about five feet high with a trench round it), and received them with a tremendous volley. The artillerymen, however, charged away pluckily, and before they had reached the wall four were killed and nine wounded. The enemy shot fiercely and aimed well.

Our brave boys stormed away, and soon some of them jumped over the wall and a hand-to-hand combat ensued. The commanding officer of the fortress, Lieutenant Marshall, was severely wounded in the leg, which fact must have had a great influence on the course of the fight, for he surrendered soon after. Some soldiers managed to escape, some were killed, about 10 wounded, and 25 were taken prisoners. No less than five artillerymen were killed and 13 wounded, amongst the latter being the valiant Lieutenant Coetsee who afterwards was cruelly murdered by kaffirs near Roos Senekal. The defenders as well as the assailants had behaved excellently.

Near Monument Hill, at some distance from the position, the burghers’ horses were left behind, and the men marched up in scattered order, in the shape of a crescent. When we arrived at the enemy’s outposts they had formed up at 100 paces from the forts, but in the dark the soldiers did not see us till we almost ran into them. There was no time to waste words. Fortunately, they surrendered without making any defence, which made our task much lighter, for if one shot had been fired, the garrison of the forts would have been informed of our approach. Only at 20 paces distance from the forts near the Monument (there were four of them), we were greeted with the usual “Halt, who goes there.” After this had been repeated three times without our taking any notice, and as we kept coming closer, the soldiers fired from all the forts. Only now could we see how they were situated. We found them to be surrounded by a barbed wire fence which was so strong and thick that some burghers were soon entangled in it, but most of them got over it.

The first fort was taken after a short but sharp defence, the usual “hurrah” of the burghers jumping into the fort was, like a whisper of hope in the dark, an encouragement to the remainder of the storming burghers, who now soon took the other forts, not without having met with a stout resistance. Many burghers were killed, amongst whom the brave Field-Cornet John Ceronie, and many were wounded.

It had looked at first as if the enemy did not mean to give in, but we could not go back, and “onward” was the watchword. In several instances there was a struggle at a few paces’ distance, only the wall of the fort intervening between the burghers and the soldiers. The burghers cried: “Hands up, you devils,” but the soldiers replied: “Hy kona,” a kaffir expression which means “shan’t.”

“Jump over the walls, my men!” shouted my officers, and at last they were in the forts: not, of course, without the loss of many valuable lives. A “melée” now followed; the English struck about with their guns and with their fists, and several burghers lay on the ground wrestling with the soldiers. One “Tommy” wanted to thrust a bayonet through a Boer, but was caught from behind by one of the latter’s comrades, and knocked down and a general hand-to-hand fight ensued, a rolling over and over, till one of the parties was exhausted, disarmed, wounded, or killed. One of the English captains (Vosburry) and 40 soldiers were found dead or wounded, several having been pierced by their own bayonets.

Some burghers had been knocked senseless with the butt-end of a rifle in the struggle with the enemy.

This carnage had lasted for twenty minutes, during which the result had been decided in our favour, and a “hurrah,” full of glory and thankfulness, came from the throats of some hundreds of burghers. We had won the day, and 81 prisoners-of-war had been made, including two officers—Captain Milner and Lieutenant Dease—both brave defenders of England’s flag.

They belonged to the Royal Irish Regiment, of which all Britons should be proud.

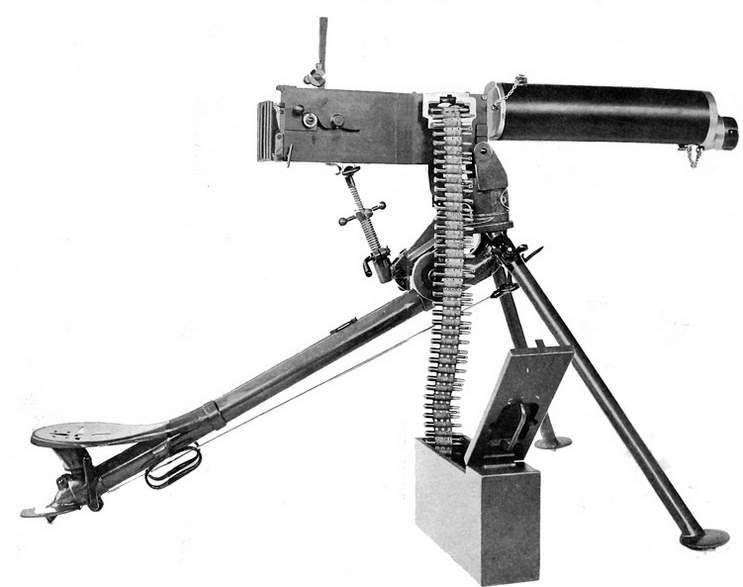

In the captured forts we found a Maxim, in perfect order, 20 boxes of ammunition, and other things, besides provisions, also a quantity of spirits, which was, however, at once destroyed, to the disappointment of many burghers.

We now pushed on to Belfast village, but found every cliff and ditch occupied. All efforts to get in touch with the commandos which meant to attack the village from the south were without avail. Besides, we did not hear a single shot fired, and did not know what had become of the attack from the south. In intense darkness we were firing at each other from time to time, so that it was not advisable to continue our operations under the circumstances, and at daybreak I told all my commandos to desist.

The attacks on Wonderfontein, Pan Station, Dalmanutha, and Machadodorp had failed.

I afterwards received a report from the commandos on the other side of the line, that, owing to the dark night, their attacks, although they were made with deliberation and great bravery, had all been unsuccessful. They had repeatedly missed the forts and had shot at one another.

General Christian Botha had succeeded in capturing some of the enemy’s outposts, and in pushing on had come across a detachment of Gordon Highlanders and been obliged to retire with a loss of 40 killed and wounded.

We found, therefore, these forts in the hands of the soldiers, who, in my opinion, belonged to the best regiments of the English army.

The guests of our Government, at “the house beautiful” near Roos Senekal were thus added to by two gentlemen, Captain Milner and Lieutenant Dease, and they were my prisoners-of-war for four months, during which time I found Captain Milner one of the most worthy British officers whom it had been my privilege to meet in this War. Not only in his manly appearance, but especially by his noble character he stood head and shoulders above his fellow-officers.

Lieutenant Dease bore a very good character but was young and inexperienced. For several reasons I am pleased to be able to make publicly these statements.

The soldiers we had made prisoners during this fight, as well as those we took at Helvetia, were given up to the British officers a few days afterwards, as we were not in a position to feed them properly, and it would not be humane or fair to keep the soldiers who had the misfortune of falling into our hands without proper food. This, of course, was a very unsatisfactory state of affairs, for we had to fight fiercely, valuable lives had to be sacrificed, every nerve had to be strained to force the enemy to surrender, and to take his positions; and then, when we had captured them, the soldiers were merely disarmed and sent back to the English lines after a little while, only to find them fighting against us once more in a few days.

The Boers asked, “Why are not these “Tommies” required to take the oath before being liberated not to fight against us again?” I believe this would have been against the rules of civilised warfare, and we did not think it chivalrous to ask a man who was a prisoner to take an oath in return for his release.

A prisoner-of-war has no freedom of action, and might have promised under the circumstances what he would not have done if he had been a free man.

CHAPTER XXXI

A “BLUFF” AND A BATTLE.

The last days of February, 1901, were very trying for our commandos on the “Hoogeveld,” south of the railway. General French, assisted by half a dozen other generals, with a force of 60,000 men, crossed the “Hoogeveld,” between the Natal border and the Delagoa Railway, driving all the burghers and cattle before him, continually closer to the Swazi frontier, in order to strike a “final blow” there.

These operations the English called “The Great Sweep of February, 1901.”

Commandant-General Botha sent word that he was in a bad plight on the “Hoogeveld,” the enemy having concentrated all his available troops upon him. I was asked to divert their attention as much as possible by repeated attacks on the railway line, and to worry them everywhere.

To attack the fortified entrenchments in these parts, where we had only just been taking the offensive, causing the enemy to be on his guard, would not have been advisable. I therefore decided to make a feint attack on Belfast.

One night we moved with all the burghers who had horses, about 15 carts, waggons, and other vehicles, guns and pom-pom, to a high “bult,” near the “Pannetjes.” When the sun rose the next morning we were in full sight of the enemy at Belfast, from which we were about ten miles away.

Here our commando was split into two parts, and the mounted men spread about in groups of fifty men each, with carts scattered everywhere among the ranks. We slowly approached Belfast in this order. Our commando numbered about 800 men, and considering the way we were distributed, this would look three times as many. We halted several times, and the heliographers, who were posted everywhere in sight of the enemy, made as much fuss as possible. Scouts were riding about everywhere, making a great display by dashing about all over the place, from one group of burghers to another. After we had waited again for some little time we moved on, and thus the comedy lasted till sunset; in fact, we had got within range of the enemy’s guns. We had received information from Belfast to the effect that General French had taken all the guns with him to Belfast, leaving only a few of small calibre, which could not reach us until we were at about 4,000 yards from the fort. Our pom-pom and our 15-pounder were divided between the two divisions, and the officers had orders to fire a few shots on Belfast at sunset. We could see all day long how the English near Monument Hill were making ditches round the village and putting up barbed wire fences.

Trains were running backwards and forwards between Belfast and the nearest stations, probably to bring up reinforcements.

At twilight we were still marching, and by the light of the last rays of the sun we fired our two valuable field-pieces simultaneously, as arranged. I could not see where the shells were falling, but we heard them bursting, and consoled ourselves with the idea that they must have struck in near the enemy. Each piece sent half a dozen shells, and some volleys were fired from a few rifles at intervals. We thought the enemy would be sure to take this last movement for a general attack. What he really did think, there is no saying. As the burghers put it, “We are trying to make them frightened, but the thing to know is, did they get frightened?” For this concluded our programme for the day, and we retired for the night, leaving the enemy in doubt as to whether we meant to give him any further trouble, yet without any apology for having disturbed his rest.

The result of this bloodless fight was nil in wounded and killed on both sides.

On the 12th of February, 1901, the first death-sentence on a traitor on our side was about to be carried out, when suddenly our outposts round Belfast were attacked by a strong British column under General Walter Kitchener. When the report was brought to our laager, all the burghers went to the rescue, in order to keep the enemy as far from the laager as possible, and beat them back. Meanwhile the outposts retired fighting all the while. We took up the most favourable positions we could and waited. The enemy did not come up close to us that evening, but camped out on a round hill between Dullstroom and Belfast and we could distinctly see how the soldiers were all busy digging ditches and trenches round the camp and putting up barbed wire enclosures. They were very likely afraid of a night attack and did not forget the old saying about being “wise in time.”

Near the spot where their camp was situated were several roads leading in different directions which left us in doubt as to which way they intended to go, and whether they wanted to attack us, or were on their way to Witpoort-Lydenburg.

The next morning, at sunset, the enemy broke up his camp and made a stir. First came a dense mass of mounted men, who after having gone about a few hundred paces, split up into two divisions. One portion moved in a westerly direction, the other to the north, slowly followed by a long file, or as they say in Afrikander “gedermte” (gut) of waggons and carts which, of course, formed the convoy. Companies of infantry, with guns, marched between the vehicles.

I came to the conclusion that they intended to attack from two sides, and therefore ordered the ranks to scatter. General Muller, with part of the burghers, went in advance of the enemy’s left flank and, as the English spread out their ranks, we did the same.

At about 9 a.m. our outposts near the right flank of the English were already in touch with the enemy, and rifle-fire was heard at intervals.

I still had the old 15-pounder, but the stock of ammunition had gone down considerably and the same may be said of the pom-pom of Rhenosterkop fame. We fired some shots from the 15-pounder at a division of cavalry at the foot of a kopje. Our worthy artillery sergeant swore he had hit them right in the centre, but even with my strong spy-glass I could not see the shells burst, although I admit the enemy showed a little respect for them, which may be concluded from the fact that they at once mounted their horses and looked for cover.

A British soldier is much more in awe of a shell than a Boer is, and the enemy’s movements are therefore not always a criterion of our getting the range. We had, moreover, only some ordinary grenades left, some of which would not burst, as the “schokbuizen” were defective, and we could not be sure of their doing any harm.

The other side had some howitzers, which began to spit about lyddite indiscriminately. They also had some quick-firing guns of a small calibre, which, however, did not carry particularly far. But they were a great nuisance, as they would go for isolated burghers without being at all economical with their ammunition.

Meanwhile, the enemy’s left reached right up to Schoonpoort, where some burghers, who held good positions, were able to fight them. This caused continual collisions with our outposts. Here, also, the assailants had two 15-pounder Armstrong’s, which fired at any moving target, and hardly ever desisted, now on one or two burghers who showed themselves, then on a tree, or an anthill, or a protruding rock. They thus succeeded in keeping up a deafening cannonade, which would have made one think there was a terrific fight going on, instead of which it was a very harmless bombardment.

It did no more harm than at the English manœuvres, although it was no doubt a brilliant demonstration, a sort of performance to show the British Lion’s prowess. I could not see the practical use of it, though.

It was only on the enemy’s right wing that we got near enough to feel some of the effect of the artillery’s gigantic efforts, which here forced us to some sharp but innocent little fights between the outposts. At about 4 o’clock in the afternoon, the British cavalry stormed our left, which was in command of General Muller. We soon repulsed them, however. Half an hour after we saw the enemy’s carts go back.

I sent a heliographic message to General Muller, with whom I had kept in close contact, to the effect that they were moving away their carts and that we ought to try and charge them on all points as well as we could.

“All right,” he answered; “shall we start at once?” I flashed back “Yes,” and ordered a general charge.

The burghers now appeared all along the extended fighting line.

The enemy’s guns, which were just ready to be moved, were again placed in position and opened fire, but our men charged everywhere, a sort of action which General Kitchener did not seem to like, for his soldiers began to flee with their guns, and a general confusion ensued. Some of these guns were still being fired at the Boers but the latter stormed away determinedly. The British lost many killed and wounded.

The cavalry fled in such a hurry as to leave the infantry as the only protection of the guns, and although these men also beat a retreat they, at least, did it while fighting.

I do not think I overstate the case by declaring that General Walter Kitchener owed it to the stubborn defence of his infantry that his carts were not captured by us that day.

Their ambulance, in charge of Dr. Mathews and four assistants, and some wounded fell into our hands, and were afterwards sent back.

We pursued the enemy as well as we could, but about nine miles from Belfast, towards which the retreating enemy was marching, the forts opened fire on us from a 4.7 naval gun and they got the range so well that lyddite shells were soon bursting about our ears.

We were now in the open, quite exposed and in sight of the Belfast forts. Two of our burghers were wounded here.

Field-Cornet Jaapie Kriege, who was afterwards killed, with about 35 burghers, was trying to cut off the enemy from a “spruit”-drift; the attack was a very brave one, but our men ventured too far, and would all have been captured had not the other side been so much in a hurry to get away from us. Luckily, too, another field-cornet realised the situation, and kept the enemy well under fire, thus attracting Kriege’s attention, who now got out of this scrape.

When night fell we left the enemy alone, and went back to our laager. The next morning the outposts reported that the would-be assailants were all gone.

How much this farce had cost General Kitchener we could not tell with certainty. An English officer told me afterwards he had been in the fight, and that their loss there had been 52 dead and wounded, including some officers. He also informed me that their object that day had been to dislodge us. If that is so, I pity the soldiers who were told to do this work.

Our losses were two burghers wounded, as already stated.

CHAPTER XXXII

EXECUTION OF A TRAITOR.

As briefly referred to in the last chapter, there occurred in the early part of February, 1901, what I always regard as one of the most unpleasant incidents of the whole Campaign, and which even now I cannot record without awakening the most painful recollections. I refer to the summary execution of a traitor in our ranks, and inasmuch as a great deal has been written of this tragic episode, I venture to state the particulars of it in full.

The facts of the case are as follows:—

At this period of the War, as well as subsequently, much harm was done to our cause by various burghers who surrendered to the enemy, and who, actuated by the most sordid motives, assisted the British in every possible way against us. Some of these treacherous Boers occasionally fell into our hands, and were tried by court martial for high treason; but however damning the evidence brought against them they usually managed to escape with some light punishment. On some occasions sentence of death was passed on them, but it was invariably commuted to imprisonment for life, and as we had great difficulty in keeping such prisoners, they generally succeeded, sooner or later, in making their escape. This mistaken leniency was the cause of much dissatisfaction in our ranks, which deeply resented that these betrayers of their country should escape scot-free.

About this time a society was formed at Pretoria, chiefly composed of surrendered burghers, called the “Peace Committee,” but better known to us as the “Hands-uppers.” Its members surreptitiously circulated pamphlets and circulars amongst our troops, advising them to surrender and join the enemy. The impartial reader will doubtless agree that such a state of things was not to be tolerated. Imagine, for example, that English officers and soldiers circulated similar communications amongst the Imperial troops! Would such proceedings have been tolerated?

The chairman of this society was a man by the name of Meyer De Kock, who had belonged to a Steenkampsberg field-cornet’s force and had deserted to the enemy. He was the man who first suggested to the British authorities the scheme of placing the Boer women and children in Concentration Camps—a system which resulted in so much misery and suffering—and he maintained that this would be the most effective way of forcing the Boers to surrender, arguing that no burgher would continue to fight when once his family was in British hands.

One day a kaffir, bearing a white flag, brought a letter from this person’s wife addressed to one of my field-cornets, informing him that her husband, Mr. De Kock, wished to meet him and discuss with him the advisability of surrendering with his men to the enemy. My field-cornet, however, was sufficiently sensible and loyal to send no reply.

And so it occurred that one morning Mr. De Kock, doubtlessly thinking that he would escape punishment as easily as others had before him, had the audacity to ride coolly into our outposts. He was promptly arrested and incarcerated in Roos Senekal Gaol, this village being at the time in our possession. Soon afterwards he was tried by court-martial, and on the face of the most damning evidence, and on perusal of a host of incriminating documents found in his possession, was condemned to death.

About a fortnight later a waggon drove up to our laager at Windhoek, carrying Lieutenant De Hart, accompanied by a member of President Burger’s bodyguard, some armed burghers, and the condemned man De Kock. They halted at my tent, and the officer handed me an order from our Government, bearing the President’s ratification of the sentence of death, and instructing me to carry it out within 24 hours. Needless to say I was much grieved to receive this order, but as it had to be obeyed I thought the sooner it was done the better for all concerned. So then and there on the veldt I approached the condemned man, and said:—

“Mr. De Kock, the Government has confirmed the sentence of death passed on you, and it is my painful duty to inform you that this sentence will be carried out to-morrow evening. If you have any request to make or if you wish to write to your family you will now have an opportunity of doing so.”

At this he turned deadly pale, and some minutes passed before he had recovered from his emotion. He then expressed a wish to write to his family, and was conducted, under escort, to a tent, where writing materials were placed before him. He wrote a long communication to his wife, which we sent to the nearest British officers to forward to its destination. He also wrote me a letter thanking me for my “kind treatment,” and requested me to forward the letter to his wife. Later on spiritual consolation was offered and administered to him by our pastor.

Next day, as related in the previous chapter, we were attacked by a detachment of General Kitchener’s force from Belfast. This kept me busy all day, and I delegated two of my subaltern officers to carry out the execution. At dusk the condemned man was blindfolded and conducted to the side of an open grave, where twelve burghers fired a volley, and death was instantaneous. I am told that De Kock met his fate with considerable fortitude.

So far as I am aware, this was the first Boer “execution” in our history. I afterwards read accounts of it in the English press, in which it was described as murder, but I emphatically repudiate this description of a wholly justifiable act. The crime was a serious one, and the punishment was well deserved, and I have no doubt that the same fate would have awaited any English soldier guilty of a similar offence. It seems a great pity, however, that no war can take place without these melancholy incidents.