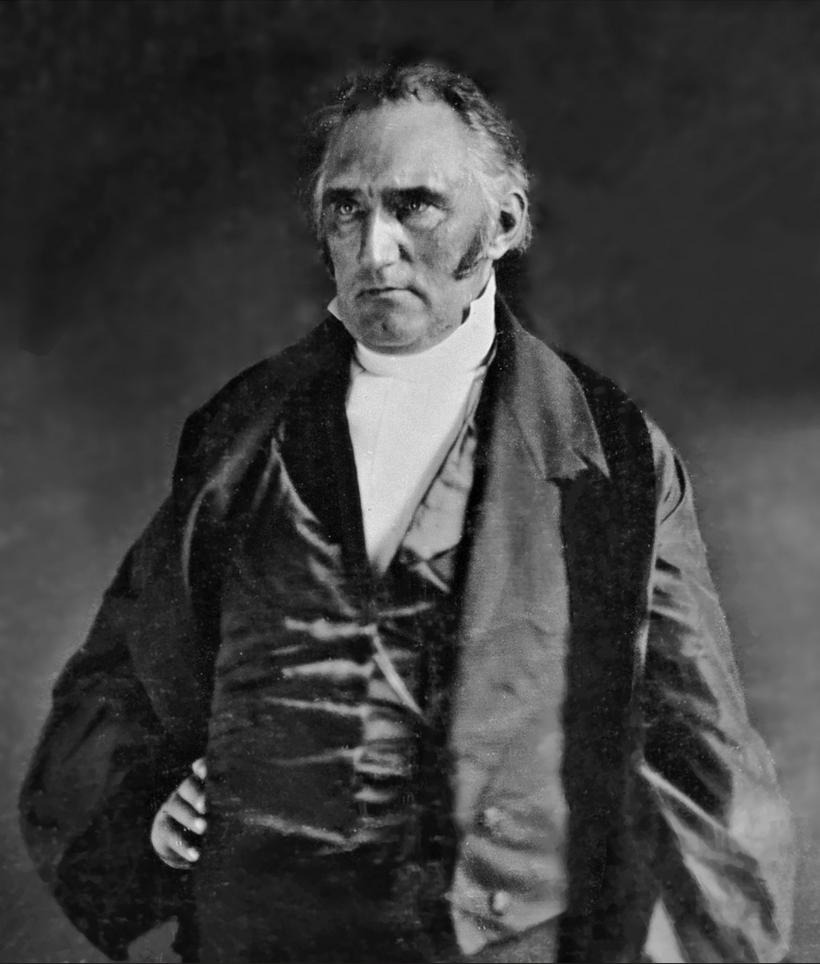

Editor’s note: The following sermon by Francis Wayland is extracted from The World’s Great Sermons, Vol. IV (published 1908).

____________________________________________________

And the apostles, when they were returned, told him all that they had done. And he took them, and went aside privately into a desert place, belonging to the city called Bethsaida. And the people when they knew it, followed him: and he received them, and spake unto them of the kingdom of God, and healed them that had need of healing. And when the day began to wear away, then came the twelve, and said unto him, Send the multitude away, that they may go into the towns and country round about, and lodge and get victuals: for we are here in a desert place. But he said unto them, Give ye them to eat. And they said, We have no more but five loaves and two fishes; except we should go and buy meat for all this people. For they were about five thousand men. And he said to his disciples, Make them sit down by fifties in a company. And they did so, and made them all sit down. Then he took the five loaves and the two fishes and looking up to heaven, he blessed them and brake, and gave to the disciples to set before the multitude. And they did eat, and were all filled: and there was taken up of fragments that remained to them twelve baskets. – Luke ix., 10-17.

It was the sagacious opinion of, I think, the late Professor Porson, that he would rather see a single copy of a daily newspaper of ancient Athens, than read all the commentaries upon the Grecian tragedies that have ever been written. The reason for this preference is obvious. A single sheet, similar to our daily newspapers, published in the time of Pericles, would admit us at once to a knowledge of the habits, manners, modes of opinion, political relations, social condition, and moral attainments of the people, such as we never could gain from the study of all the writers that have ever attempted to illustrate the nature of Grecian civilization.

The same remark is true in respect to our knowledge of the character of individuals who have lived in a former age. What would we not, at the present day, give for a few pages of the private diary of Julius Cesar, or Cicero, or Brutus, or Augustus; or for the minute reminiscences of any one who had spent a few days in the company of either of these distinguished men? What a flood of life would the discovery of such a manuscript throw upon Roman life, but especially upon the private opinions, the motives, the aspirations, the moral estimates of the men whose names have become household words throughout the world! A few such pages might, perchance, dissipate the authority of many a bulky folio on which we now rely with implicit confidence. Not only would the characters of these heroes of antiquity stand out in bolder relief than they have ever done before, but the individuals themselves would be brought within the range of our personal sympathy; and we should seem to commune with them as we do with an intimate acquaintance.

It is worthy of remark, that we are favored with a larger portion of this kind of information, respecting Jesus of Nazareth, than almost any other distinguished person that has ever lived. He left no writings Himself; hence all that we know of Him has been written by others. The narrators, however, were the personal attendants, and not the mere auditors or pupils of their master. The apostles were members of the family of Jesus; they traveled with Him, on foot, throughout the length and breadth of Palestine; they partook with Him of his frugal meals, and bore with Him the trial of hunger, weariness, and want of shelter; they followed Him through the lonely wilderness and the crowded street; they saw His miracles in every variety of form, and listened to His discourses in public as well as to His explanations in private. Hence their whole narrative is instinct with life; a vivid picture of Jewish manners and customs, rendered more definite and characteristic by the moral light which then, for the first time, shone upon it. Hence it is that these few pages are replete with moral lessons that never weary us in the perusal, and which have been the source of unfailing illumination to all succeeding ages.

The verses which I have read, as the text of this discourse, may well be taken as an illustration of all that I have here said. They may, without impropriety, be styled a day in the life of Jesus of Nazareth. By observing the manner in which our blessed Lord spent a single day, we may form some conception of the kind of life which He ordinarily led; and we may, perchance, treasure up some lessons which it were well if we should exemplify in our daily practice.

The place at which these events occurred was near the head of the Sea of Galilee, where it receives the waters of the upper Jordan. This was one of the Savior’s favorite places of resort. Capernaum, Chorazin, and Bethsaida, all in this immediate vicinity, are always spoken of in the gospels as towns which enjoyed the largest share of His ministerial labors, and were distinguished most frequently with the honor of His personal presence. The scenery of the neighborhood is wild and romantic. To the north and west, the eye rests on the lofty summits of Lebanon and Hermon. To the south, there opens upon the view the blue expanse of the lake, enclosed by frowning rocks, which here and there jut over far into the waters, and then again retire towards the land, leaving a level beach to invite the labors of the fishermen. The people, removed at a considerable distance from the metropolis of Judea, cultivated those rural habits with which the simple tastes of the Savior would most readily harmonize. Near this spot was also one of the most frequented fords of the Jordan, on the road from Damascus to Jerusalem; and thus, while residing here, He enjoyed unusual facilities for disseminating throughout this whole region a knowledge of those truths which He came on earth to promulgate.

Some weeks previous to the time in which the events spoken of in the text occurred, our Lord had sent His disciples to announce the approach of the kingdom of heaven, in all the cities and villages which He Himself proposed to visit. He conferred on them the power to work miracles, in attestation of their authority, and of the divine character of Him by whom they were sent. He imposed upon them strict rules of conduct, and directed them to make known to every one who would hear them the good news of the coming dispensation. As soon as He sent them forth, He Himself went immediately abroad to teach and to preach in their cities. As their Master and Lord, He might reasonably have claimed exemption from the personal toil and the rigid self-denials to which they were by necessity subjected. But He had laid no claim to such exemption. He commenced without delay the performance of the very same duties which He had imposed upon them. He felt himself under obligation to set an example of obedience to His own rules. “The Son of Man,” said He, “came not to be ministered unto, but to minister, and to give His life a ransom for many.” “Which,” said He, “is greater, he that sitteth at meat, or he that serveth? but I am among you as He that serveth.” Would it not be well, if, in this respect, we copied more minutely the example of our Lord, and held ourselves responsible for the performance of the very same duties which we so willingly impose upon our brethren? We best prove that we believe an act obligatory, when we commence the performance of it ourselves. Many zealous Christians employ themselves in no other labor than that of urging their brethren to effort. Our Savior acted otherwise. In this respect, His example is specially to be imitated by His ministers. When they urge upon others a moral duty, they must be the first to perform it. When they inculcate an act of self-denial, they themselves must make the noblest sacrifice. Can we conceive of anything which could so much increase the moral power of the ministry, and rouse to a flame the dormant energy of the churches, as obedience to this teaching of Christ by the preachers of His gospel?

It seems that the Savior had selected a well-known spot, at the head of the lake, for the place of meeting for his apostles, after this their first missionary tour had been completed. “The apostles gathered themselves unto Jesus, and told Him all things, both what they had done, and what they had taught.” There is something delightful in this filial confidence which these simple-hearted men reposed in their almighty Redeemer. They told Him of their success and their failure, of their wisdom and their folly, of their reliance and their unbelief. We can almost imagine ourselves spectators of this meeting between Christ and them, after this their first separation from each other. The place appointed was most probably some well-known locality on the shore of the lake, under the shadow of its overhanging rocks, where the cool air from the bosom of the water refreshed each returning laborer, as he came back beaten out with the fatigues of travel, under the burning sun of Syria. You can imagine the joy with which each drew near to the Master, after this temporary absence; and the honest greetings with which every newcomer was welcomed by those who had chanced to arrive before him. We can seem to perceive the Savior of men listening with affectionate earnestness to the recital of their various adventures; and interposing, from time to time, a word either of encouragement or of caution, as the character and circumstances of each narrator required it. The bosom of each was unveiled before the Searcher of Hearts, and the consolation which each one needed was bestowed upon him abundantly. The toilsomeness of their journey was no longer remembered, as each one received from the Son of God the smile of His approbation. That was truly a joyful meeting. Of all that company there is not one who has forgotten that day; nor will he forget it ever. With unreserved frankness they told Jesus of all that they had done, and what they had taught; of all their acts, and all their conversations. “Would it not be better for us, if we cultivated more assiduously this habit of intimate intercourse with the Savior? Were we every day to tell Jesus of all that we have done and said; did we spread before Him our joys and our sorrows, our faults and our infirmities, our successes and our failures, we should be saved from many an error and many a sin. Setting the Lord always before us, He would be on our right hand, and we should not be moved. “He that dwelleth in the secret place of the most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty.”

The Savior perceived that the apostles needed much instruction which could not be communicated in a place where both He and they were so well known. They had committed many errors, which He preferred to correct in private. By doing His will, they had learned to repose greater confidence in His wisdom, and were prepared to receive from Him more important instruction. But these lessons could not be delivered in the hearing of a promiscuous audience. Nor was this all. He perceived that the apostles were worn out with their labors, and needed repose. Surrounded as they were by the multitude, which had already begun to collect about them, rest and retirement were equally impossible. “There were many coming and going, and they had no leisure, even so much as to eat.” He therefore said to them, “Come ye yourselves apart into a desert place, and rest a while.” For this purpose, He “took ship, and crossed over with his disciples alone, and went into a desert place belonging to Bethsaida.”

The religion of Christ imposes upon us duties of retirement, as well as duties of publicity. The apostles had been for some time past before the eyes of all men, preaching and working miracles. Their souls needed retirement. “Solitude,” said Cecil, “is my great ordinance.” They would be greatly improved by private communion both with Him and with each other. It was for the purpose of affording them such a season of moral recreation, that our Lord withdrew them from the public gaze into a desert place. Nor was this all. Their labor for some weeks past had been severe. They had traveled on foot under a tropical sun, reasoning with unbelievers, instructing the ignorant, and comforting the cast-down. Called upon, at all hours, both of the day and night, to work cures on those that were oppressed with diseases, their bodies, no less than their spirits, needed rest. Our Lord saw this, and He made provision for it. He withdrew them from labor, that they might find, tho it were but for a day, the repose which their exhausted natures demanded. The religion of Christ is ever merciful, and ever consistent in its benevolence. It is thoughtful of the benefactor as well as the recipient. It requires of us all labor and self-sacrifice, but to these it affixes a limit. It never commands us to ruin our health and enfeeble our minds by unnatural exhaustion. It teaches us to obey the laws of our physical organization, and to prepare ourselves for the labors of to-morrow by the judiciously conducted labors of today. It was on this principle that our Lord conducted His intercourse with His disciples. “He knew their frame, and remembered that they were dust.” May we not from this incident derive a lesson of practical instruction? I well know that there are persons who are always sparing themselves, who, while it is difficult to tell what they do, are always complaining of the crushing weight of their labors, and who are rather exhausted with the dread of what they shall do, than with the experience of what they have actually done. It is not of those that we speak. Those who do not labor have no need of rest. It is to the honest, the painstaking, the laborious, that we address the example in the text. We sometimes meet with the industrious, self-denying servant of Christ, in feeble health, and with an exhausted nature, bemoaning his condition, and condemning himself because he can accomplish no more, while so much yet remains to be done. To such a one we may safely present the example of the blessed Savior. When His apostles had done to the utmost of their strength, although the harvest was great, and the laborers few, He did not urge upon them additional labor, nor tell them that because there was so much to be done they must never cease from doing. No; He tells them to turn aside and rest for a while. It is as though He had said, “Your strength is exhausted; you cannot be qualified for subsequent duty until you be refreshed. Economize, then, your power, that you may accomplish the more.” The Savior addresses the same language to us now. When we are worn down in His service, as in any other, He would have us rest, not for the sake of self-indulgence, but that we may be the better prepared for future effort. We do nothing at variance with His will, when we, with a good conscience, use the liberty which he has thus conceded to us. Jesus, with His disciples, crossed the water, and entered the desert; that is, the sparsely inhabited country of Bethsaida. Desert, or wilderness, in the New Testament, does not mean an arid waste, but pasture land, forest, or any district to which one could retire for seclusion. Here, in the cool and tranquil neighborhood of the lake, he began to instruct His disciples, and, without interruption, make known to them the mysteries of the kingdom. It was one of those seasons that the Savior Himself rarely enjoyed. Everything tended to repose: the rustling leaves, the rippling waves, the song of the birds, heard more distinctly in this rural solitude, all served to calm the spirit ruffled by the agitations of the world, and prepared it to listen to the truths which unveil to us eternity. Here our Lord could unbosom Himself, without reserve, to His chosen few, and hold with them that communion which He was rarely permitted to enjoy during His ministry on earth.

Soon, however, the whole scene is changed. The multitude, whom he had so recently left, having observed the direction in which He had gone, have discovered the place of His retreat. An immense crowd approaches, and the little company is surrounded by a dense mass of human beings pressing upon them on every side. These are, however, only the pioneers. At last, five thousand men, besides women and children, are beheld thronging around them.

Some of these suitors present most importunate claims. They are in search of cure for diseases which have baffled the skill of the medical profession, and, as a last resort, they have come to the Messiah for aid. Here was a parent bringing a consumptive child. There were children bearing on a couch a paralytic parent. Here was a sister leading a brother blind from his birth, while her supplications were drowned by the shout of a frenzied lunatic who was standing by her side. Every one, believing his own claim to be the most urgent, pressed forward with selfish importunity. Each one, caring for no other than himself, was striving to attain the front rank, while those behind, disappointed, and fearing to lose this important opportunity, were eager to occupy the places of those more fortunate than themselves. The necessary tumult and disorder of such a scene you can better imagine than I can describe.

This was, doubtless, by no means a welcome interruption. The apostles needed the time for rest; for they were worn out in the public service. They wanted it for instruction; for such opportunities of intercourse with Christ were rare. But what did they do? Did our Lord inform the multitude that this day was set apart for their own refreshment and improvement, and that they could not be interrupted? As He beheld them approaching, did He quietly take to His boat, and leave them to go home disappointed? Did He plead His own convenience, or His need of repose, as any reason for not attending to the pressing necessities of His fellow men?

No, my brethren, very far from it. That providence of God had brought these multitudes before Him, and that same providence forbade Him to send them away unblessed. He at once broke up the conference with His disciples and addressed Himself to the work before Him. His instructions were of inestimable importance; but I doubt if even they were as important as the example of deep humility, exhaustless kindness, and affecting compassion which He here exhibited. When the Master places work before us which can be done at no other time, our convenience must yield to other men’s necessities. “The Son of Man came not to be ministered unto, but to minister.” You can imagine to yourself the Savior rising from His seat, in the midst of His disciples, and presenting Himself to the approaching multitudes. His calm dignity awes into silence this tumultuous gathering of the people. Those who came out to witness the tricks of an empiric, or listen to the ravings of a fanatic, find themselves, unexpectedly, in a presence that repels every emotion but that of profound veneration. The light-hearted and frivolous are awestruck by the unearthly majesty that seems to clothe the Messiah as with a garment. And yet it was a majesty that shone forth conspicuous, most of all, by the manifestation of unparalleled goodness. Every eye that met the eye of the Savior quailed before Him; for it looked into a soul that had never sinned; and the spirit of the sinner felt, for the first time, the full power of immaculate virtue.

Thus the Savior passed among the crowd, and “healed all that had need of healing.” The lame walked, the lepers were cleansed, the blind received their sight, the paralytic were restored to soundness, and the bloom of health revisited the cheeks of those that but just now were sick unto death.

The work to be done for the bodies of men was accomplished, and there yet remained some hours of the summer’s day unconsumed. The power and goodness displayed in this miraculous healing would naturally predispose the people to listen to the instructions of the Savior. This was too valuable an opportunity to be lost. Our Lord therefore proceeded to speak to them of the things concerning the kingdom of God. We can seem to perceive the Savior seeking an eminence from whence He could the more conveniently address this vast assembly. You hear Him unfold the laws of God’s moral government. He unmasks the hypocrisy of the Pharisees; He rebukes the infidelity of the Sadducees; He exposes the folly of the frivolous, as well as of the selfish worldling; He speaks peaceably to the humble penitent; He encourages the meek, and comforts those that be cast down. The intellect and the conscience of this vast assembly are swayed at His will.

The soul of man bows down in reverence in the presence of its Creator. “He stilleth the noise of the seas, the noise of their waves, and the tumult of the people.” As He closes His address, every eye is moistened with compunction for sin. Every soul cherishes the hope of amendment. Every one is conscious that a new moral light has dawned upon his soul, and that a new moral universe has been unveiled to his spiritual vision. As the closing words of the Savior fell upon their ears, the whole multitude stood for a while unmoved, as though transfixed to the earth by some mighty spell; until, at last, the murmur is heard from thousands of voices, “Never man spake like this man.”

But the shades of evening are gathering around them. The multitude have nothing to eat. To send them away fasting would be inhuman, for divers of them came from far, and many were women and children, who could not perform their journey homeward without previous refreshment. To purchase food in the surrounding towns and villages would be difficult; but even were this possible, whence could the necessary funds be provided? A famishing multitude was thus unexpectedly cast upon the bounty of our Lord. He had not tempted God by leading them into the wilderness. They came to Him of themselves, to hear His words and to be healed of their infirmities. He could not “send them away fasting, lest they should faint by the way.” In this dilemma, what was to be done? He puts this question to His disciples, and they can suggest no means of relief. The little stock of provisions which they had brought with them was barely sufficient for themselves. They can perceive no means whatever by which the multitude can be fed, and they at once confess it.

The Savior, however, commands the twelve to give them to eat. They produce their slender store of provisions, amounting to five loaves and two small fishes. He commands the multitude to sit down by companies on the grass. As soon as silence is obtained, He lifts up His eyes to heaven, and supplicates the blessing of God upon their scanty meal. He begins to break the loaves and fishes, and distribute them to His disciples, and His disciples distribute them to the multitude. He continues to break and distribute. Basket after basket is filled and emptied, yet the supply is undiminished. Food is carried in abundance to the famishing thousands. Company after company is supplied with food, but the five loaves and two fishes remain unexhausted. At last, the baskets are returned full, and it is announced that the wants of the multitude are supplied. The miracle then ceases, and the multiplication of food is at an end.

But even here the provident care of the Savior is manifested. Although this food has been so easily provided, it is not right that it be lightly suffered to perish. Christ wrought no miracles for the sake of teaching men wastefulness. That food, by what means soever provided, was a creature of God, and it were sin to allow it to decay without accomplishing the purposes for which it was created. “Gather up the fragments,” said the Master of the feast, “that nothing be lost.” “And they gathered up the fragments that remained, twelve baskets full.”

Dissimilar as are our circumstances to those of our Lord, we may learn from this latter incident a lesson of instruction.

In the first place, as I have remarked, the Savior did not lead the multitude into the wilderness without making provision for their sustenance. This would have been presumption. They followed Him without His command, and He found Himself with them in this necessity. He had provided for His own wants, but they had not provided for theirs. The providence of God had, however, placed Him in His present circumstances, and He might therefore properly look to providence for deliverance. This event, then, furnishes the rule by which we are to be governed. When we plunge ourselves into difficulty, by a neglect of the means or by a misuse of the faculties which God has bestowed upon us, it is to be expected that He will leave us to our own devices. But when, in the honest discharge of our duties, we find ourselves in circumstances beyond the reach of human aid, we may then confidently look up to God for deliverance. He will always take care of us while we are in the spot where He has placed us. When He appoints for us trials, He also appoints for us the means of escape. The path of duty, though it may seem arduous, is ever the path of safety. We can more easily maintain ourselves in the most difficult position, God being our helper, than in apparent security relying on our own strength.

The Savior, in full reliance upon God, with only five loaves and two fishes, commenced the distribution of food amongst the vast multitude. Though His whole store was barely sufficient to supply the wants of His immediate family, He began to share it with the thousands who surrounded Him. Small as was His provision at the commencement, it remained unconsumed until the deed of mercy was done, and the wants of the famished host supplied. Nor were the disciples losers by this act of charity. After the multitude had eaten and were satisfied, twelve baskets full of fragments remained, a reward for their deed of benevolence.

From this portion of the narrative, we may, I think, learn that if we act in faith, and in the spirit of Christian love, we may frequently be justified in commencing the most important good work, even when in possession of apparently inadequate means. If the work be of God, He will furnish us with helpers as fast as they are needed. In all ages, God has rewarded abundantly simple trust in Him, and has bestowed upon it in the highest honor. We must, however, remember the conditions upon which alone we may expect His aid, lest we be led into fanaticism. The service which we undertake must be such as God has commanded, and His providence must either designate us for the work, or, at least, open the door by which we shall enter upon it. It must be God ‘s work, and not our own; for the good of others, and not for the gratification of our own passions; and, in the doing of it, we must, first of all, make sacrifice of ourselves, and not of others. Under such circumstances, there is hardly a good design which we may not undertake with cheerful hopes of success, for God has promised us His assistance. ” If God be for us, who can be against us?” The calculations of the men of this world are of small account in such a matter. It would have provoked the smile of an infidel to behold the Savior commencing the work of feeding five thousand men with a handful of provisions. But the supply increased as fast as it was needed, and it ceased not until all that He had prayed for was accomplished.

Perhaps, also, we may learn from this incident another lesson. If I mistake not, it suggests to us that in works of benevolence we are accustomed to rely too much on human, and too little on divine, aid. When we attempt to do good, we commence by forming large associations, and suppose that our success depends upon the number of men whom we can unite in the promotion of our undertaking. Every one is apt thus to forget his own personal duty, and rely upon the labor of others, and it is well if he does not put his organization in the place of God Himself. Would it not be better if we made benevolence much more a matter between God and our own souls, each one doing with his own hands, in firm reliance on divine aid, the work which Providence has placed directly before him? Our Lord did not send to the villages round to organize a general effort to relieve the famishing. In reliance upon God, He set about to work Himself , with just such means as God had afforded Him. All the miracles of benevolence have, if I mistake not, been wrought in the same manner. The little band of disciples in Jerusalem accomplished more for the conversion of the world than all the Christians of the present day united. And why? Because every individual Christian felt that the conversion of the world was a work for which he himself, and not an abstraction that he called the Church, was responsible. Instead of relying on man for aid, every one looked up directly to God, and went forth to the work.

God was thus exalted, the power was confessed to be His own, and, in a few years, the standard of the Cross was carried to the remotest extremities of the then known world.

Such has, I think, been the case ever since. Every great moral reformation has proceeded upon principles analogous of these. It was Luther, standing up alone in simple reliance upon God, that smote the Papal hierarchy; and the effects of that blow are now agitating the nations of Europe. Roger Williams, amid persecution and banishment, held forth that doctrine of soul-liberty which, in its onward march, is disenthralling a world. Howard, alone, undertook the work of showing mercy to the prisoner, and his example is now enlisting the choicest minds in Christendom in this labor of benevolence. Clarkson, unaided, a young man, and without influences, consecrated himself to the work of abolishing the slave trade; and, before he rested from his labor, his country had repented of and forsaken this atrocious sin. Raikes saw the children of Gloucester profaning the Sabbath day; he set on foot a Sabbath school on his own account, and now millions of children are reaping the benefit of his labors, and his example has turned the attention of the whole world to the religious instruction of the young. With such facts before us, we surely should be encouraged to attempt individually the accomplishment of some good design, relying in humility and faith upon Him who is able to grant prosperity to the feeblest effort put forth in earnest reliance on His almightiness. Such were the occupations that filled up a day in the life of Jesus of Nazareth. There was not an act done for Himself; all was done for others. Every hour was employed in the labor which that hour set before Him. Private kindness, the relief of distress, public teaching, and ministration to the wants of the famishing, filled up the entire day. Let His disciples learn to follow His example. Let us, like Him, forget ourselves, our own wants, and our own weariness, that we may, as he did, scatter blessings on every side, as we move onward in the pathway of our daily life. If such were the occupations of the Son of God, can we do more wisely than to imitate His example? Every disciple would then be as a city set upon a hill, and men, seeing our good works, would glorify our Father who is in heaven. “Then would our righteousness go forth as brightness, and our salvation as a lamp that burneth.”