Editor’s note: The following sermon by Henry Charles Beeching is extracted from Inns of Court Sermons (published 1901). All spelling in the original.

Editor’s note: The following sermon by Henry Charles Beeching is extracted from Inns of Court Sermons (published 1901). All spelling in the original.

“Because I will do this unto thee, prepare to meet thy God, O Israel.” — Amos iv. 12.

As we read this Book of Amos now, its chapters make on us much the same impression as other passages of the Old Testament that rebuke the sins of men; they are fierce, full of passion, full of an imminent judgment; and as we read we acquiesce, because we acknowledge God to be a holy God, whose eyes cannot look upon evil; and yet, notwithstanding, the whole perhaps has only the most distant interest for us, like thunder heard remote.

But there was a time when these words of Amos, which to us so readily commend themselves, were like foolishness and like blasphemy. To those who first heard them they seemed the ravings of a madman not to be listened to; or perhaps, it would be truer to say, like the ravings of an atheist, to be heard only with pity. The story belongs to the reign of Jeroboam, the son of Joash, when the kingdom of Israel was at the height of its glory and its frontier extended beyond the farthest point reached in the brightest days of Solomon.

Being so victorious and so prosperous the people had thankful hearts; the ancient sanctuaries of the land — Bethel, where their father Jacob had seen the vision of angels; Gilgal, where the shame of their uncircumcision had been rolled away; Dan, Mizpeh, Shechem — were crowded with worshippers, and the people even made pilgrimages right down to Beer-sheba in the south, where their father Abraham had dug a well. And the guilds of the prophets which Samuel had founded, now so many years ago, rejoiced in this revival of religion, and bade the people expect the speedy advent of the “great day of the Lord,” when all the nations would be gathered together from far to do homage to the nation of Jehovah.

The scene of this prophetic book is laid at Bethel, the most ancient and the most important of all the sanctuaries in Israel, on the occasion of a great festival. Amaziah, the priest in charge, has offered sacrifice for the people; and they are lying stretched at a solemn feast, singing songs with harp and tabor to God who gives His people corn and wine, and peace in their borders. And then, in the midst of these songs of thanksgiving, there is suddenly heard the shrill “discordant wail of the Eastern mourner.”[1] “The virgin of Israel is fallen ; she shall no more rise: she lies prostrate in her own land; there is none to lift her up.” And they look; and in the midst of them stands a poor son of the desert, a herdman — “a beater of sycamore trees.” Amaziah takes him to be some crazy prophet from Judah, who has been attracted by the festival, and has come to see if he can make a little money by startling the worshippers; and though, perhaps remembering another prophet who had appeared before at Bethel, he thinks it best to send the king word — because prophecies against the reigning house had sometimes a sudden and bloody way of fulfilling themselves — yet his main feeling seems to have been one of contemptuous pity for the poor intruder, reduced to prophesying for a piece of bread. “O thou seer, go, flee thee away into the land of Judah, and there eat bread, and prophesy there: but prophesy not again any more at Bethel: for it is the king’s chapel.”

Now what did Amos come to Bethel to say? What, in the time of this great prosperity, did he mean by denouncing the fall of the kingdom of Israel — “the virgin of Israel is fallen”? He saw two things: he saw, first, that the religion of the people had nothing to do with morality; that it was divorced from common honesty and clean living. Their commerce had made some of them rich, and that had only made them want to be richer. In the course of the hundred years’ war between Israel and Damascus, the old peasant proprietors, each with his few acres, had vanished; and the land was held by a few wealthy holders, who let it at excessive rents, and when the tenants could not pay, lent money at excessive rates.

That was bad enough; but the lot of the poor became intolerable owing to the fact that there was no justice in the land. The judges were the priests; and the penalty they inflicted for wrongdoing was not imprisonment, but a costly sacrifice or a money fine paid to the sanctuary; and when wrongs came to be regarded by the priests as a source of income, it is not hard to understand that there was no justice for the poor; and that a rich man might do anything he could pay for.

That explains why Amos is so fierce against the sacrifices at Bethel and Gilgal. It is not that they in themselves were anything but right, for they were the recognised mode of worship; it is because they were considered a sufficient atonement for every sort of dishonesty and fraud: as if a man amongst us were to think that the alms he gave at the Holy Communion made up for defrauding his fellows all the week; as if recognising the existence of God absolved a man from obeying Him. No, says Amos, but because you know God, because God has revealed Himself to you, therefore He will visit upon you your iniquities. Because it is you who recognise that Jehovah is a judge, and come to His sanctuary and to His priests for your legal decisions, therefore on you shall His righteous judgment fall. Do you call Jehovah a judge, and do you think that in consequence He can be bribed with offerings? Who taught you such religion as that? Thus saith the Lord, “I hate, I despise your feast-days. I have no pleasure in your solemn assemblies. Though ye offer me burnt-offerings, and your meat offerings, I will not accept them; neither will I regard the peace-offerings of your fat beasts. But let justice run down like waters, and righteousness as a mighty stream. Seek ye me, saith the Lord; seek not Bethel or Beer-sheba; seek me.”

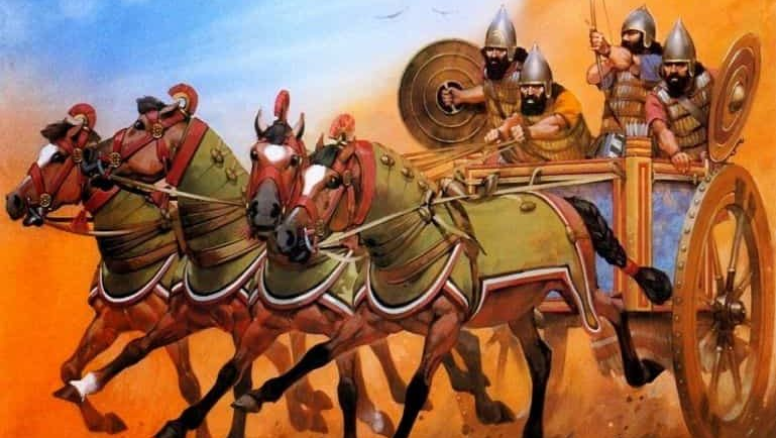

This then was the first thing Amos saw, that although the land was full of religion, it was as full of iniquity; which, God being judge, could not go unpunished. In the next place he saw that the punishment was near. On the horizon was a cloud that would spread itself and overwhelm them, the great conquering empire of the Assyrians. Amos nowhere mentions the Assyrians by name, but the people knew whom he meant. That made the treason of his prophecy, to think that the kingdom could be overthrown; and that also made the blasphemy of it, to prophesy that Jehovah’s people could fall before the heathen. The people knew quite as well as Amos that their land was in danger from the Assyrians, for it was through the Assyrian weakening of Damascus, with whom they had fought for years, that they had been able to extend their borders; and now that Damascus had fallen, nothing stood between them and the Assyrians. But for all that, they had no fear: they put their trust in the God of their fathers. “Jehovah is his name.” Slowly, very slowly, by the words of the prophets interpreting their repeated deliverances, especially through the work of Elijah and Elisha, the nation had come firmly to believe that they were the nation of Jehovah: “Them only had he known of all the families of the earth.” By His stretched-out arm they had conquered the nations round about; the gods of the nations had fallen down before Jehovah. Who compared with Him was Baal or Moloch? Rimmon of Damascus had fallen; Chemosh had not saved Moab from His anger, nor Milcom the children of Ammon. There was none like unto the God of Jeshurun. “Happy art thou, O Israel: who is like unto thee, O people saved by Jehovah, the shield of thy help, and the sword of thy excellency! The God of old is thy refuge, and underneath are the everlasting arms.” And now that Asshur, the god of the Assyrians, was leading on his nation against them, it would be seen once more which of the two was the Lord of Hosts. And so they redoubled their sacrifices, and were confident of the issue.

And what had Amos to tell them about this impending struggle between Jehovah and Asshur? He told them that it was not Asshur but Jehovah who was leading the Assyrian army against them. We are so accustomed to the truth that God is the God of all flesh, that He has made of one blood all the nations of men, that we can hardly throw our imagination back to a time when this great fact was a new and startling revelation. But that is the truth Amos is labouring to impart to his countrymen; that although God had known them only of all the nations, yet it was He who guided the blind movements of all the wandering peoples of the earth. “Are ye not as the children of the Ethiopians unto me, O children of Israel? saith the Lord. Have not I brought up Israel out of the land of Egypt, and the Philistines from Caphtor, and the Syrians from Kir?” I, not Dagon, not Rimmon, as you think and they think; I Jehovah, the Creator of the whole world.

“I am he that maketh the seven stars and Orion, and turneth the shadow of death into the morning, and maketh the day dark with night: that calleth for the waters of the sea, and poureth them out upon the face of the earth; that formeth the mountains, and createth the wind, and declareth unto man what is his thought, that maketh the morning darkness, and treadeth upon the high places of the earth. Jehovah, the God of Hosts, is his name.” Yes, the God of Hosts — as the Israelites were so proud to call Him; but of what hosts? Not of the hosts of Israel merely; they were but as dust in the balance.

And so, because it was not Asshur but Jehovah that was bringing up the Assyrian army against them, Amos bade the people prepare to meet Him. That sentence, “Prepare to meet thy God,” which has almost lost power to arrest us from being placarded in waiting-rooms and stencilled on the pavement of our streets, had a terrible significance as it first comes into Scripture. It meant, the God of your nation is bringing up an army against His own people; when you prepare yourselves for battle, it will be to fight against your own God, who is advancing against you. “Prepare to meet thy God, O Israel.”

Such, roughly, is the substance of this prophecy of Amos; and I suggest to your thought his dramatic story to-day, because it will serve to bring home to our minds two or three practical lessons of which, in time of war, a nation sorely stands in need. It teaches us that there is a false confidence in God as being on our side, which does not command success. It reminds us that a nation may have to prepare to meet its own God at the head of the opposing host. Some people may have been puzzled by the fact that both the opposing armies in the present terrible war [2] are Christian men, who go into battle with prayers on their lips, and celebrate their victories with psalms. This ancient prophet will teach us, that God may hate our psalms and our prayers now, as He hated the Israelitish sacrifices long ago, if the heart that offers them cares nothing for justice, nothing for righteousness. And then, he will wipe out of our minds, if we will let him, the idea that any nation, however favoured by God, Israelite or Boer or Briton, can base upon that favour any claim upon God’s help that the opposing nation has not equally. God is the God of all the world. We cannot claim Him as an ally in any sense that will not hold also of the other side. The confidence that comes from the idea that God has “chosen” any one nation for His own people in such a sense that His credit is pledged to help them out of all their difficulties, is a false confidence that must end sooner or later in pitiful disappointment. This is false confidence, because it takes no account of the character of God, and of the aims, the necessarily moral aims, that God has in view. God chooses men and nations not for their merits, but to do certain work. The God whom the Bible reveals to us is a God whose interest is in men’s character; a God who gave men commandments; a God of righteousness, whose cry to men is, “Are your minds set on righteousness, O ye congregation?” “Blessed are they that hunger and thirst after righteousness.” If God be such a God as that, it is sheer folly to suppose that His help can be in any way tied to the fortunes of a particular people, even though He had originally elected them for a great purpose; even though He still keeps that purpose in view. On the contrary, it has often been seen that, both for men and nations, the valley of humiliation has been the door of hope: that defeat and shame have saved them, and given them once more a desire to carry out the true purpose of their election.

But those who contend most strenuously against reducing God to the level of a partisan, are sometimes tempted to fall into as great an error by practically denying that God can be interested in the fortunes of any nation at all. They have not taken the step Amos would have them take, from worshipping a national God, to worshipping a God of righteousness, whose one care is that of righteousness, and who has pledged Himself to punish sin, as in individuals, so also in nations. The God they have come to believe in is very little more than an abstraction, a formula; they believe in righteousness, rather than in the God of righteousness, and so they have a horror of appeals to Him to aid this cause or that, as though to pray was to bring human passions into an air too serene for such violence. It troubles them that we should pray for victory; we seem to be repeating the error of the Israelites, in invoking a merely tutelary deity. But the same argument would put a stop to our prayers for every social object, for all the National Institutions for which your prayers are bidden before every sermon here. And if these things are too concrete for the divine interest and care, how can we dare to pray for merely individual blessings? Such an abstract deity as this would be, is not the Christian God. Our final authority for God’s nature is the picture He gave us of Himself in the only-begotten Son. “He that hath seen me,” said Christ, “hath seen the Father.” If so, we have but to ask, whether the interest of our Lord in His own generation, in the individuals of it, and in the whole nation collectively, was less than that of the people of His day? Was it not far greater?

“And when he was come near, he beheld the city, and wept over it, saying, If thou hadst known, even thou, at least in this thy day, the things which belong unto thy peace!”

If a nation then may be destroyed by God as a punishment for unrighteousness, or gathered closer into the protection of the Almighty arms, may we not deprecate that destruction and entreat this protection? And if we do so, must we not in the same breath ask for the forgiveness of our sins? To humble ourselves as a nation before God in penitence is not, as some would represent it, a bribe to the Almighty; if it were, it would be a happy bribery, felix culpa, a bribery that we could be content to see spreading far and wide. But did any son of man ever say to God: “I will cleanse my heart, if you will give me victory”! He has said sometimes, “I will sacrifice my dearest,” but could he say “I will cleanse my heart,” on such and such terms? Do not believe it. Rather the truth is, that no one can pray honestly and intelligently to God for anything, without at the same time praying for the forgiveness of his sins. To come into God’s presence at all, is to be overcome with the prophet’s sense of shame — “Woe is me! for I am a man of unclean lips”; and therefore even to the petition for daily bread must always be annexed “Forgive us our trespasses.” It is often by being in trouble that we learn to pray: we cannot but pray for our friends in danger, for our country in perplexity; and as we kneel in church, or by our bedside, the thought comes home to our hearts, “God is of purer eyes than to behold evil. I am praying to Him for victory; for my child’s life; for my brother’s or husband’s life; am I praying from a clean heart? If I incline unto wickedness in my heart, the Lord cannot hear me.”

Dear brethren, the wisdom of our forefathers set apart these days of Lent for earnest self-examination. When God’s special judgments are in the world, there is a special call for such examination. May God grant us all the courage to face ourselves, who are ever our own worst enemies; to face ourselves, and learn the truth; may He grant us the courage to meet Him as a friend, that we may not have to meet Him as a foe; and may He grant us grace to amend our lives according to His holy word.

___________________________________

[1] It will be obvious how much this description of Amos and his time owes to Robertson Smith’s Prophets of Israel.

[2] The Second Boer War (1899-1902). [ed.]