Editor’s note: The following sermon by Dr. Thomas Arnold is extracted from The World’s Best Orations, Vol. I, by David J. Brewer (published 1899).

_________________________________________________________________

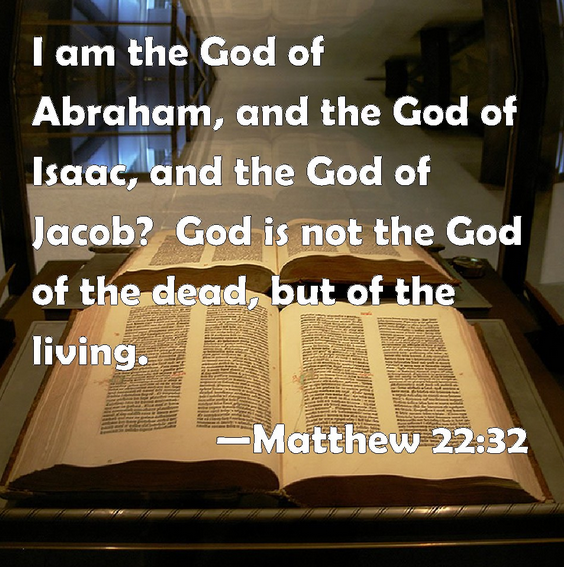

“God is not the God of the dead, but of the living.”—Matt. xxii. 32

_________________________________________________________________

We hear these words as a part of our Lord’s answer to the Sadducees; and, as their question was put in evident profaneness, and the answer to it is one which to our minds is quite obvious and natural, so we are apt to think that in this particular story there is less than usual that particularly concerns us. But it so happens, that our Lord, in answering the Sadducees, has brought in one of the most universal and most solemn of all truths,—which is indeed implied in many parts of the Old Testament, but which the Gospel has revealed to us in all its fullness,—the truth contained in the words of the text, that “God is not the God of the dead, but of the living.”

I would wish to unfold a little what is contained in these words, which we often hear even, perhaps, without quite understanding them; and many times oftener without fully entering into them. And we may take them, first, in their first part, where they say that “God is not the God of the dead.”

The word “dead,” we know, is constantly used in Scripture in a double sense, as meaning those who are dead spiritually, as well as those who are dead naturally. And, in either sense, the words are alike applicable: “God is not the God of the dead.”

God’s not being the God of the dead signifies two things: that they who are without Him are dead, as well as that they who are dead are also without Him. So far as our knowledge goes respecting inferior animals, they appear to be examples of this truth. They appear to us to have no knowledge of God; and we are not told that they have any other life than the short one of which our senses inform us. I am well aware that our ignorance of their condition is so great that we may not dare to say anything of them positively; there may be a hundred things true respecting them which we neither know nor imagine. I would only say that, according to that most imperfect light in which we see them, the two points of which I have been speaking appear to meet in them: we believe that they have no consciousness of God, and we believe that they will die. And so far, therefore, they afford an example of the agreement, if I may so speak, between these two points; and were intended, perhaps, to be to our view a continual image of it. But we had far better speak of ourselves. And here, too, it is the case that “God is not the God of the dead.” If we are without Him we are dead; and if we are dead we are without Him: in other words, the two ideas of death and absence from God are in fact synonymous.

Thus, in the account given of the fall of man, the sentence of death and of being cast out of Eden go together; and if any one compares the description of the second Eden in the Revelation, and recollects how especially it is there said, that God dwells in the midst of it, and is its light by day and night, he will see that the banishment from the first Eden means a banishment from the presence of God. And thus, in the day that Adam sinned, he died; for he was cast out of Eden immediately, however long he may have moved about afterwards upon the earth where God was not. And how very strong to the same point are the words of Hezekiah’s prayer, “The grave cannot praise thee, Death cannot celebrate thee; they that go down into the pit cannot hope for thy truth”; words which express completely the feeling that God is not the God of the dead. This, too, appears to be the sense generally of the expression used in various parts of the Old Testament, “Thou shalt surely die.” It is, no doubt, left purposely obscure; nor are we ever told, in so many words, all that is meant by death; but, surely, it always implies a separation from God, and the being—whatever the notion may extend to—the being dead to Him. Thus, when David had committed his great sin, and had expressed his repentance for it, Nathan tells him, “The Lord also hath put away thy sin; thou shalt not die”: which means, most expressively, thou shalt not die to God. In one sense David died, as all men die; nor was he by any means freed from the punishment of his sin: he was not, in that sense, forgiven; but he was allowed still to regard God as his God; and, therefore, his punishments were but fatherly chastisements from God’s hand, designed for his profit, that he might be partaker of God’s holiness. And thus, although Saul was sentenced to lose his kingdom, and although he was killed with his sons on Mount Gilboa, yet I do not think that we find the sentence passed upon him, “Thou shalt surely die;” and, therefore, we have no right to say that God had ceased to be his God, although he visited him with severe chastisements, and would not allow him to hand down to his sons the crown of Israel. Observe, also, the language of the eighteenth chapter of Ezekiel, where the expressions occur so often, “He shall surely live,” and “He shall surely die.” We have no right to refer these to a mere extension on the one hand, or a cutting short on the other, of the term of earthly existence. The promise of living long in the land, or, as in Hezekiah’s case, of adding to his days fifteen years, is very different from the full and unreserved blessing, “Thou shalt surely live.” And we know, undoubtedly, that both the good and the bad to whom Ezekiel spoke died alike the natural death of the body. But the peculiar force of the promise, and of the threat, was, in the one case, Thou shalt belong to God; in the other, Thou shalt cease to belong to Him; although the veil was not yet drawn up which concealed the full import of those terms, “belonging to God,” and “ceasing to belong to Him”: nay, can we venture to affirm that it is fully drawn aside even now?

I have dwelt on this at some length, because it really seems to place the common state of the minds of too many amongst us in a light which is exceedingly awful; for if it be true, as I think the Scripture implies, that to be dead, and to be without God, are precisely the same thing, then can it be denied that the symptoms of death are strongly marked upon many of us? Are there not many who never think of God or care about His service? Are there not many who live, to all appearances, as unconscious of His existence as we fancy the inferior animals to be? And is it not quite clear, that to such persons, God cannot be said to be their God? He may be the God of heaven and earth, the God of the universe, the God of Christ’s Church; but he is not their God, for they feel to have nothing at all to do with Him; and, therefore, as he is not their God, they are, and must be, according to the Scripture, reckoned among the dead.

But God is the God “of the living.” That is, as before, all who are alive, live unto Him; all who live unto Him are alive. “God said, I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob;” and, therefore, says our Lord, “Abraham, and Isaac, and Jacob are not and cannot be dead.” They cannot be dead because God owns them; He is not ashamed to be called their God; therefore, they are not cast out from Him; therefore, by necessity, they live. Wonderful, indeed, is the truth here implied, in exact agreement, as we have seen, with the general language of Scripture; that, as she who but touched the hem of Christ’s garment was, in a moment, relieved from her infirmity, so great was the virtue which went out from Him; so they who are not cast out from God, but have anything: whatever to do with Him, feel the virtue of His gracious presence penetrating their whole nature; because He lives, they must live also.

Behold, then, life and death set before us; not remote (if a few years be, indeed, to be called remote), but even now present before us; even now suffered or enjoyed. Even now we are alive unto God or dead unto God; and, as we are either the one or the other, so we are, in the highest possible sense of the terms, alive or dead. In the highest possible sense of the terms; but who can tell what that highest possible sense of the terms is? So much has, indeed, been revealed to us, that we know now that death means a conscious and perpetual death, as life means a conscious and perpetual life. But greatly, indeed, do we deceive ourselves, if we fancy that, by having thus much told us, we have also risen to the infinite heights, or descended to the infinite depths, contained in those little words, life and death. They are far higher, and far deeper, than ever thought or fancy of man has reached to. But, even on the first edge of either, at the visible beginnings of that infinite ascent or descent, there is surely something which may give us a foretaste of what is beyond. Even to us in this mortal state, even to you advanced but so short a way on your very earthly journey, life and death have a meaning: to be dead unto God or to be alive to Him, are things perceptibly different.

For, let me ask of those who think least of God, who are most separate from Him, and most without Him, whether there is not now actually, perceptibly, in their state, something of the coldness, the loneliness, the fearfulness of death? I do not ask them whether they are made unhappy by the fear of God’s anger; of course they are not: for they who fear God are not dead to Him, nor He to them. The thought of Him gives them no disquiet at all; this is the very point we start from. But I would ask them whether they know what it is to feel God’s blessing, For instance: we all of us have our troubles of some sort or other, our disappointments, if not our sorrows. In these troubles, in these disappointments,—I care not how small they may be,—have they known what it is to feel that God’s hand is over them; that these little annoyances are but His fatherly correction; that He is all the time loving us, and supporting us? In seasons of joy, such as they taste very often, have they known what it is to feel that they are tasting the kindness of their heavenly Father, that their good things come from His hand, and are but an infinitely slight foretaste of his love? Sickness, danger,—I know that they come to many of us but rarely; but if we have known them, or at least sickness, even in its lighter form, if not in its graver,— have we felt what it is to know that we are in our Father’s hands, that He is with us, and will be with us to the end; that nothing can hurt those whom He loves? Surely, then, if we have never tasted anything of this: if in trouble, or in joy, or in sickness, we are left wholly to ourselves, to bear as we can, and enjoy as we can; if there is no voice that ever speaks out of the heights and the depths around us, to give any answer to our own; if we are thus left to ourselves in this vast world,—there is in this a coldness and a loneliness; and whenever we come to be, of necessity, driven to be with our own hearts alone, the coldness and the loneliness must be felt. But consider that the things which we see around us cannot remain with us, nor we with them. The coldness and loneliness of the world, without God, must be felt more and more as life wears on: in every change of our own state, in every separation from or loss of a friend, in every more sensible weakness of our own bodies, in every additional experience of the uncertainty of our own counsels,—the deathlike feeling will come upon us more and more strongly: we shall gain more of that fearful knowledge which tells us that “God is not the God of the dead.”

And so, also, the blessed knowledge that he is the God “of the living” grows upon those who are truly alive. Surely he “is not far from every one of us.” No occasion of life fails to remind those who live unto Him, that He is their God, and that they are His children. On light occasions or on grave ones, in sorrow and in joy, still the warmth of his love is spread, as it were, all through the atmosphere of their lives: they forever feel His blessing. And if it fills them with joy unspeakable even now, when they so often feel how little they deserve it; if they delight still in being with God, and in living to Him, let them be sure that they have in themselves the unerring witness of life eternal:—God is the God of the living, and all who are with Him must live.

Hard it is, I well know, to bring this home, in any degree, to the minds of those who are dead: for it is of the very nature of the dead that they can hear no words of life. But it has happened that, even whilst writing what I have just been uttering to you, the news reached me that one, who two months ago was one of your number, who this very half-year has shared in all the business and amusements of this place, is passed already into that state where the meanings of the terms life and death are become fully revealed. He knows what it is to live unto God and what it is to die to Him. Those things which are to us unfathomable mysteries, are to him all plain: and yet but two months ago he might have thought himself as far from attaining this knowledge as any of us can do. Wherefore it is clear, that these things, life and death, may hurry their lesson upon us sooner than we deem of, sooner than we are prepared to receive it. And that were indeed awful, if, being dead to God, and yet little feeling it, because of the enjoyments of our worldly life these enjoyments were of a sudden to be struck away from us, and we should find then that to be dead to God is death indeed, a death from which there is no waking and in which there is no sleeping forever.

Sermon: The Realities of Life and Death

Latest from Religion

The Weimar Years – Part 1

This started out as an attempt to better understand Weimar Germany by chronicling my reactions to the audiobook version of “The Weimar Years: Rise and Fall 1918-1933” by Frank McDonough. Writing my

Alfredus Rex Fundator

"Alfred was a Christian hero, and in his Christianity he found the force which bore him, through calamity apparently hopeless, to victory and happiness."

The Story of Cortez

It seemed to me that, having to speak tonight to soldiers, that I ought to speak about soldiers. Some story, I thought, about your own profession would please you most and teach

The Coming of the Friars

When King Richard of England, whom men call the Lion-hearted, was wasting his time at Messina, after his boisterous fashion, in the winter of 1190, he heard of the fame of Abbot

“Joseph” by Charles Kingsley

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The Works of Charles Kingsley, Vol. 25 (published 1885). (Preached on the Sunday before the Wedding of the Prince of Wales. March 8th, third Sunday