Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Stories of American History, by N. S. Dodge (published 1879).

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Stories of American History, by N. S. Dodge (published 1879).

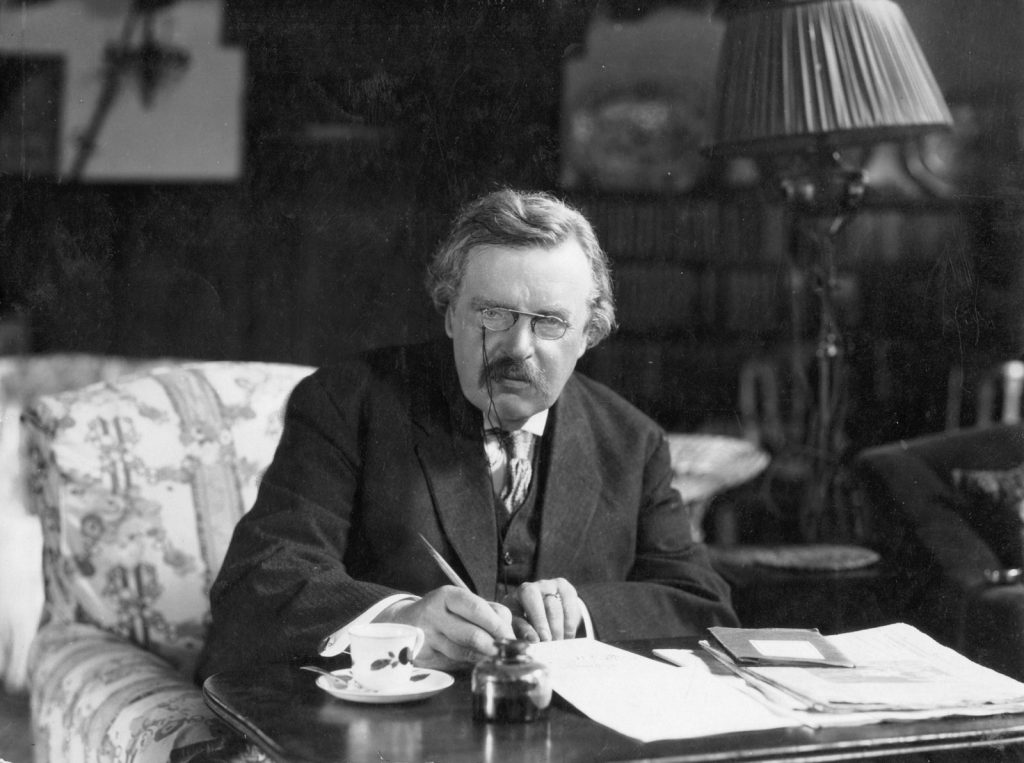

In New England, a hundred years ago, the people were mainly mechanics and farmers. There were, indeed, clergymen, and physicians, and merchants. But everybody else turned the soil or plied a trade. General Pomeroy was one of these last. He was both farmer and blacksmith. His ancestors had been blacksmiths. It was a family trade. The anvil on which his great-grand father had forged muskets in England, was in his shop. That old first settler made guns so true to their mark, that the colony of Massachusetts Bay wanted him. Under the shadows of Mount Tom there was a tract of rich land which they voted should be his, if he would come from Connecticut and make guns. He accepted the offer and removed to Massachusetts.

Seth, his descendant, grew to be such a large, fine fellow, that he was made captain of a militia company when he was only twenty, and before he was thirty he was created major and fought at Cape Breton. Then, ten years after, he was at Crown Point, and was promoted colonel. That was almost seventeen years before the Revolutionary war; and by that time Colonel Seth was getting well into his sixties. But it did not matter. He no sooner heard about Lexington, than, like an old war-horse, he snuffed the approaching troubles. “There is something coming,” he said, “that will make the ears of George III tingle; and whatever it is, I want to be in it.”

The day before the battle of Bunker Hill, there came, riding rapidly up to the old homestead in Easthampton, a man inquiring for Colonel Pomeroy.

“He is taking his afternoon nap, sir,” said a young woman, who came to the door; “walk into the house, and I will call him.”

“Give him this letter, please, Miss,” replied the man, “and let me have some refreshments immediately, for I must be back to Cambridge tomorrow.”

“Cambridge tomorrow,” exclaimed the girl, as she left the room; “Cambridge tomorrow! Is there to be fighting, then?” .

The stranger had no time to reply, before Colonel Pomeroy, in his shirt-sleeves, entered the room.

“Sergeant Smith, I suppose?” he asked. “The bearer of this letter?”

“Yes, Colonel,” was the reply.

“Well, get what food you want, and be ready to start back instantly. I will bear you company.”

“But you won’t ride to Cambridge tonight, father,” said the girl. “Think of your rheumatism!”

“They want me,” replied the veteran soldier; “Ward wants me. There is something coming off tomorrow, and they want me there. Tell Lem to saddle the black mare, and do you get my epaulets.”

There was no use in expostulation. The two started at four o’clock in the afternoon, rode to Brookfield, obtained fresh horses, rode on to Marlborough and got others, and hastened onward. All night long, through the woods and past the churches and over the hills, they sped their way. They were weary enough when the morning sun lighted up Beacon Hill; for 115 miles had been ridden in 15 hours. But the great guns of the ships and the batteries on the wharves were in active play, pouring their terrible fire into Charlestown, and it meant fighting. The old soldier would not shirk duty. When honor called, and country was in danger, life to him was as nothing, and into the thickest of the fight he was bound to go.

“I won’t ride the mare across the ‘neck,'” said the old hero; “she may be hit.”

“But it is safer to ride than walk,” answered the sergeant.

“That may be,” he replied; “but this is a borrowed horse. Take her to the tavern yonder, and I will cross on foot.”

The sergeant led the animal back, while Colonel Pomeroy, shouldering his musket, hurried across to the battle.

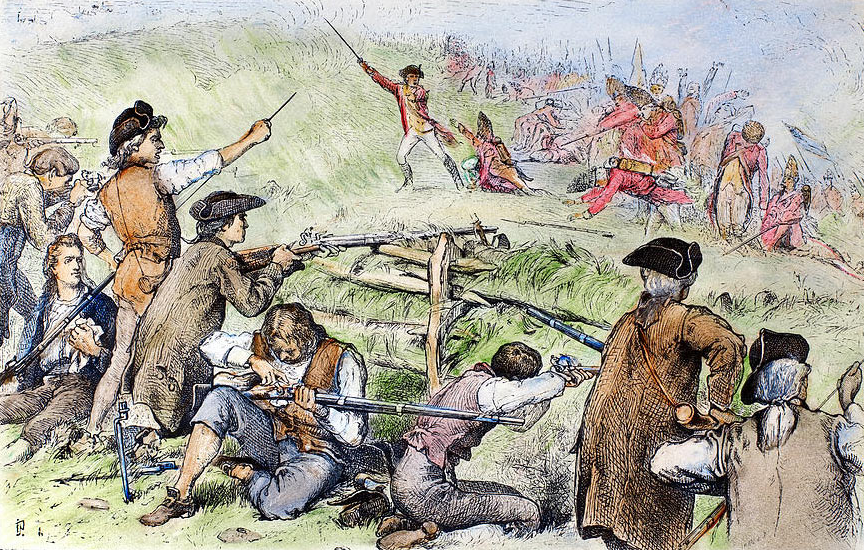

How he took command of the raw troops alongside the rail fence; how he cheered them when they grew weary; how he fought with his gun until a British ball indented the barrel; how, when the enemy gained the ground, he was the last man to leave; and how he beat British soldiers back once and again with the breech of his gun, — everybody knew in those days. He led his men in good order off the hill, and his descendants still show his battered musket.

Congress soon made Pomeroy a general. Infirm as he grew to be, he would not return home. He loved his country better than ease. “You have served in two wars already,” said Washington to him one day. “You have done your duty well, general. Go home and make guns for us, and we will use them.”

“Not yet,” said the veteran. “I shall not leave the field till you disgrace me, or the bearers carry me.”

Pomeroy was a good specimen of a Bay State man in the grand old days. No one ever doubted his word, his honor, or his courage. He was a thrifty man, and knew how to make money. He might have staid from the war and become rich, but he preferred love of country to wealth, and honor was dearer to him than gold. He died at Peekskill, in the gloomiest time of the Revolution, true to his country to the last.

Seth Pomeroy: Gunsmith, Soldier, Patriot

Latest from Culture

Dangerous Left Wing Rhetoric

On Saturday, July 13, 2024, an assassin came within inches of murdering Donald Trump on a live broadcast. Democrat talking heads immediately split into two camps: some said Trump staged the shooting

Movie Review: Streets of Fire

Underrated. Yes, the acting is forced, the lines are flat, the sets limited, but it makes up for it by being awesome. It's more of a modern Western than anything.

Calvin Coolidge on Independence Day

Speech Given July 1926 We meet to celebrate the birthday of America. The coming of a new life always excites our interest. Although we know in the case of the individual that

Edward the Black Prince

"Valiant and gentle...the flower of all chivalry in the world at that time.”

The Weimar Years – Part 5

Summary of the German Revolution, 1918-1919.