Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 10 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 9: Jaro Sunday)

_________________________________________________________________________

“Even if our earthly bodies perish on this island, our spirits will forever remain here, continuing to attack our arch enemies and defending and protecting forever our divine fatherland of Nippon.”

(Hyosigi in the Japanese “Davao News”)

__________________________________________________________________________

An old man trudged through the puddles, singing. Balanced on his head he carried a case of beer. The natives of Jaro returned from the hills. They celebrated their liberation by guzzling large stocks of beer and sake abandoned by the Japanese. Trim-bodied girls paraded their finery among the ruined buildings. “Buffaloes” and tanks, trucks, “Alligators” and jeeps rumbled through the muddy streets toward the front. Sheets of muck splashed upon the revelers. Though many of the younger women, bare-legged and laughing, were out in flashing silks, the men and children wore only rags.

Commercially the town was dead. The Japanese had killed all trade. They had fixed all prices, then bought out the merchandise with worthless money. The stores were wrecked and empty. Only here and there a rooster was swapped for a piece of American soap; then the soldier would walk off, his shoulders swinging, the cackling rooster dangling from his pack.

A Japanese found hiding in an attic was hacked to death by the crowd. Bands of guerillas descended from their mountain hideouts. Some carried old American rifles. Others bore captured Arisakas. Still others were armed with shotguns made from lengths of lead piping, with bolos, spears, and spiked clubs. They arrested every member of the pro-Japanese Bureau of Constabulary they could find, and after that they began arresting one another. Several guerilla chieftains appointed themselves to the post of Mayor of Jaro and made speeches praising freedom and insulting their rivals. American patrols endeavored to disarm the more unruly among the straw-hatted partisans, and the citizens of Jaro gloated. Patriotic banditry had become a habit during the Japanese occupation. It had often been guerilla practice to strip villagers of pigs and chickens “in the name of the fight against the Japanese.” Plain thieves who had collected pigs and rice “for the liberation,” then sold their loot to the Japs, had been no rarity; though when caught by bona fide guerillas the scoundrels were hanged feet up and head down in an ant-heap, and skeletons still dangled in the plantations. A Jaro lawyer made a speech, telling the people that the time was past when it was necessary to feed the irregulars a dozen pigs to make them strong enough to kill a Jap. The Americans would now kill Japs gratis. A guerilla group promptly carried off the lawyer as a “good neighbor”— i.e., collaborator. It was difficult to control the various patriotic bands. Collecting and hiding arms had long been a favorite sport of the barrio men in the hills. The civic disputes of Jaro were finally settled by Colonel Alva Carpenter, the Civil Affairs Officer of the Division.

While artillery thundered, the younger of the populace frolicked in outlying streets. With liberation, the rigid chaperonage system of Spanish days broke down, briefly, in Jaro as in other towns overrun in the campaign. Dancing on the flat, stinking earth between the nipa huts began at sundown and continued until dawn. Tawny maidens who had not had a piece of good soap in years, flashed their dark eyes, wriggled their bodies and laughed often. Jap rice, wine bottles, K-ration tins and struggling couples littered the slatted bamboo floors of the shacks. But the free-and-easy welcome ended quickly. (Three days later only prostitutes made dates and prices soared sky-high.) Infantry marched out of Jaro at dawn, dog-tired, silent, dirty and grim, and the morning breeze brought into town the stench of corpses decomposing on the road to Tunga.

In emergency cemeteries behind the front native labor gangs dug graves. Quartermaster trucks hauled the unpainted wooden crosses. At the edge of soggy acres lay the American dead. Their silent forms, stiffened as they had fallen, lay wrapped in blankets, or in weather-beaten tent cloth, only their muddy boots protruding. To each cross a “dog-tag” was nailed; a dead man’s name, the name of his faraway home town, the name of his mother or his wife. Gently the dead were placed into their graves. Those still alive were too busy in battle to attend. There were only the laborers of the burial detail, guards armed with carbines, and there was the chaplain’s voice booming beneath the hiss-wails of artillery shells speeding through the rain. At times, also, there was the crack of some sniper’s weapon aimed at the lonely man before the open graves.

Near Jaro a chaplain reading the burial service saw the ground about him cut by bullets. The enemy gunner sat hidden in a fringe of brush. Bullets struck into the body of one already dead. The chaplain dived behind a pile of freshly dug earth. His escort, Captain J. J. Mason of Colonial Beach, Virginia, crept toward the fringe of the jungle to locate the Jap. Again the Jap fired. This time he was only yards away. Bullets clipped branches above Captain Mason. Attracted by the firing, a squad of rifle men infiltrated the thicket. They found the sniper in a hollow tree stump and filled him with lead. The chaplain rose. His voice rang over the graves. Artillery thundered. Overhead a Cub plane circled.

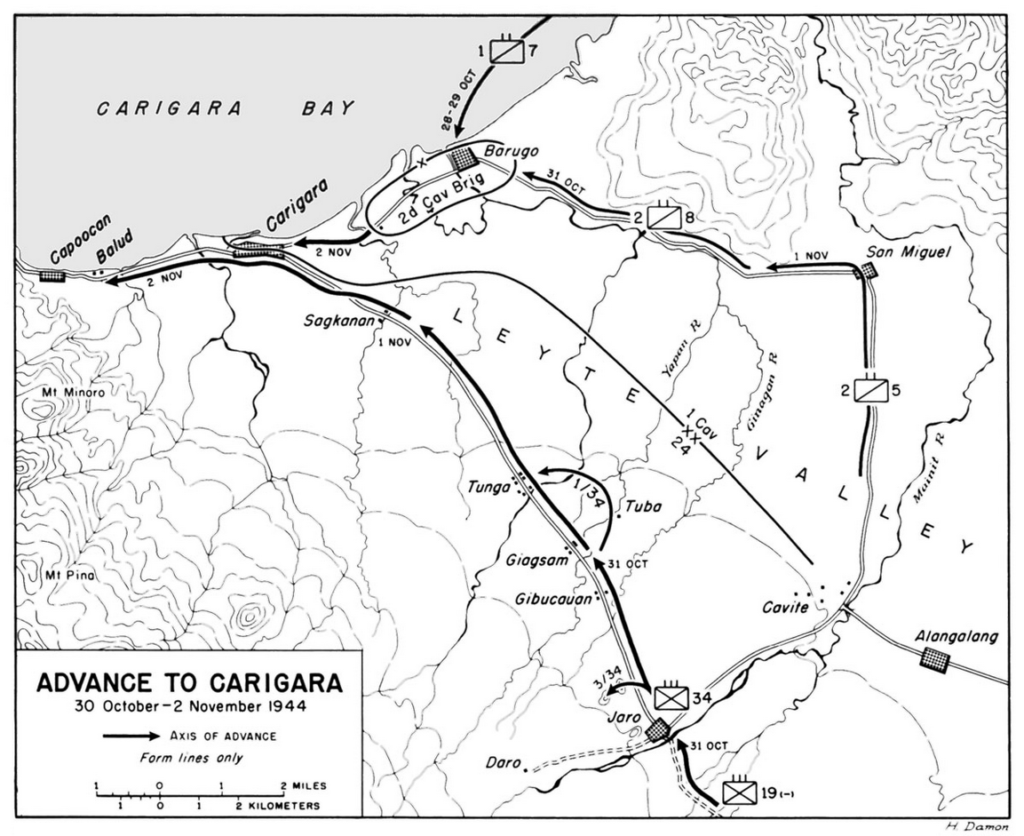

The artillery barrage laid down between Jaro and Tunga stopped at 8 a.m. At 8:20 a.m. October 31, the Thirty-Fourth Infantry resumed the attack, Carigara its goal.

“Love” Company advanced upon the rear of the ridge from which the Japanese had defied its assault the previous day. ‘Item” Company plowed north astride the road. “King” Company followed in reserve.

By 9:30 a.m. “Love” Company had arrived at the base of the ridge. The sky had cleared and the sun shone bright and hard. Except for solitary shots by snipers along their course, there was no evidence of the strong enemy force of the day before. But the blood-letting of the past had made the men cautious. In front of them lay a ravine. It was filled with gloom and jungle, and with the odor of stagnant water. What lurked in this draw? The company took covered positions. Private Ray Wyatt of Wilkesboro, North Carolina, volunteered to go forward and look.

“Who of you guys’ll go with me?” he drawled.

Two other soldiers volunteered. They advanced toward the draw. Where the grass was short, they crawled on their bellies. They peered into the wall of thickets growing down the steep defile. There was no sound, no sign of life. “No Japs,” Wyatt’s comrades said.

“I can smell ’em,” said Wyatt.

He raised his rifle and fired into the murk of tangled vegetation. An echo rang from the hillside. The crackle of Arisaka rifles followed. Wyatt and his helpers dashed along the edge of the draw. They fired into the bushes as they ran. At some spots the volume of enemy bullets ebbed away, at others it swelled viciously. Then a machine gun sputtered.

“Let’s get the hell out of here,” said Wyatt.

They ran at a crouch. Bullets twanged past their ears. Back in “Love” Company’s ranks an automatic rifle gunner named Ellis Rich, from Pineville, Kentucky, realized that Wyatt and his patrol would be mowed down before they could reach the company’s line — if nothing was done. So he stood up in full view of the Japs and fired his B.A.R. toward the edge of the ravine. The enemy gunners drew in their heads.

The draw was plastered with mortar shells until the jungle burned. Then “Love” Company stormed the position.

Simultaneously other companies pushed down the Jaro-Carigara highway. They came to a stream and found the bridge burned down. The infantrymen forded the stream. Before the scouts had reached the far bank, heavy fire rattled down from that side of the ridge which flanked the road. From the dark green of the slope came the taunting yells of Japs. The attack force split: two platoons pushed across the stream and on along roadside ditches to a position from where they could assault the reverse side of the ridge. Another group, supported by a tank, left the road and toiled up the forward slope. But tanks are nigh useless in tropical terrain. Soon mortar fire fell, and the tank withdrew.

Infantrymen charged the crest of the hill. They reached the top and drove out the Japanese with bullets and grenades. However, they discovered another defended hill not far away. The maps showed no trace of this second hill. From it squalls of fire nailed the platoons to the ground.

Soldiers lugged heavy machine guns to the crest of the captured ridge. A tank accompanied by an assault group circled the ridge. A short, massive artillery barrage prepared the way. In a double attack the battle teams lashed out at the second height. The charge carried the summit. The trapped defenders plunged down the rear slope and charged “Love” Company’s positions. “Love” Company fell back under the impact, then held, and most Japs died in a furious three-hour fight.

On the right flank of the assault the leader of a machine gun squad, Private Stephen Mizen of River Grove, Illinois, led his team of four over rough terrain to join a company he had been ordered to reinforce. When he arrived at the designated spot on a knoll he found that the company had maneuvered to another position. His squad was alone. At this time an enemy force at the base of the knoll counter attacked. Mizen saw the Japanese darting up the slope through clumps of kunai and scrub palm. He knew that if the foe recaptured the knoll, there would be nothing to prevent him from breaking through to the Carigara Road. “We’ll stay,” Mizen decided. “Set up quick.” The machine gun was mounted in less than fifteen seconds. “Give her the works,” said Mizen. The machine gun hammered. Rifles cracked. The Japanese burst out in high-pitched screeching. The counter charge was repulsed.

In a gorge between the hills a crew of litter bearers was engaged in carrying away our wounded. They were harassed by snipers lurking in the underbrush. Private Hollis Hedeen, of Milwaukee, noticed their plight. He ran to a bluff on the slope.

It gave him a fair field of fire. It also exposed him to Jap eyes. There, kneeling, he engaged a bevy of snipers some fifty yards off. It was five against one. The corpsmen and their patients passed safely. Hollis Hedeen threw out his arms, pitched forward, fatally wounded.

A platoon skirting high ground stopped in its tracks under an abrupt fire from artillery pieces, from mortars, machine guns and snipers’ rifles. During the first moment of stunned surprise three men were wounded. Among them was William H. Collins, the scout. The platoon retreated into a gully. Collins remained forward. Aid men dashed up. Collins pointed to the other wounded. “Get those fellows out first.” He could not walk. While aid men helped the other two wounded away, the injured scout shielded their retreat with covering fire from his Garand. Only then did he follow them, half rolling, half pulling himself through the vines with his hands.

In the same test of loyalty a company commander fell. There was a threat of panic. Clarence Stubbs of Minneapolis, a lieutenant leading a platoon, quickly took charge. He scrambled about, directing his men to new positions. Stubbs was hit twice. He brushed off the corpsmen who came to carry him away until the company was safe.

A rifle squad descended the northern slope of the ridge. It was met by machine gun fire as the men emerged from the hill side thickets. Ahead of them lay an open field. In the center of this field stood a nipa hut on stilts. The hostile machine gun was firing from a hole dug under that hut. The hostile gunners were invisible. They were shooting through a slit built into a wall of earth. It was an almost perfect position: the gun’s grazing bullets were able to cover every square foot of the fronting field.

“Let’s knock the son-of-a-bitch out,” said Sergeant William Byess of Chatsworth, Illinois, leader of the squad.

The riflemen hesitated. They knew what a machine gun could do.

“Call for mortars,” someone suggested. “Set the shack afire.”

Byess did not want to wait for a mortar. He detailed three men to creep around to the left, three men to creep around to the right. He put his automatic rifle gunner into a clump of bushes from where the B.A.R. man could fire at the emplacement’s port. With the remaining three men of the squad he undertook the frontal attack.

“Watch my signals,” he said.

Byess crawled out into the meadow. His daring inspired the others to follow his example. The Jap gun spat fire. The three miniature assault teams moved forward in alternating rushes. Approached from three sides, the machine gun could not fire on all three groups at the same time. While it pinned down one, the others advanced. Rifles barked and the B.A.R. in the clump of bushes rippled angrily. Soon the sweating men were close enough to hurl grenades.

Parallel to the skirmishing for the commanding heights, another battalion of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment drove down the road toward Tunga. “Easy” Company formed the point of the drive. In the sodden countryside far off the road, patrols protected the flanks of the advance. Lead scout for a flank patrol was Private Orville Franks of Portland, Indiana. Upon his alertness depended the life of his patrol, the security of his company, the continuity of his battalion’s offensive. Franks pushed through swamp, across meadows and strips of plantation, aggressive and lithe, as a good scout should be. And suddenly he stopped.

Outlined against the foliage ahead was a small, round head, an immobile face. Slowly the scout melted to the ground. He motioned his patrol to halt. Then he moved forward without making a sound.

Beyond the enemy watcher in the brush were other enemies. There were three, their shoulders hunched over a machine gun whose muzzle showed through overhanging leaves. The machine gun pointed toward the road. The slant-eyed gunners were observing “Easy” Company’s progress toward Tunga. Presently the company would move into their line of fire.

Franks raised his rifle. He fired four times. The ambush was destroyed.

Later that day a Japanese artillery barrage pinned down the advance. Mortars and automatic weapons added their rough chimes. Wounded men cried for help. Orville Franks hastened hither and yon over the mushy terrain, carrying helpless comrades to the rear. For an hour he toiled, sweating across the frontiers of death, not thinking of himself. Until an artillery shell blasted the earth from under his feet. Then it was too late to think. The scout clawed the mud. To his mother the Army sent a Silver Star Medal and “regrets.”

Another scout of a vanguard squad was Private Rudolph Sillato. “Be careful,” his wife Bridget had written him from Rochester, New York. But this day Sillato’s patrol became the target of a Jap machine gun firing from a range of about sixty yards. When a machine gun fires at you, you duck. You know that its bullets can carry death over a thousand yards and more. You hug the earth while bullets pass over you with harsh sibilance. Your urge is not to move an inch. Your urge is to sink into the ground and to stay there.

Sillato knew that the battalion was moving up the road. Something must be done to warn it. He crawled through grass and thorns while the machine gun fired. Then he crawled across the road where the Japs would surely see him. He reached a ditch, and after that he ran to carry his intelligence to the leader of the foremost platoon. The platoon maneuvered, encircling the ambush, and destroyed it.

At 11:30 a.m. “Easy” Company reached the swift-flowing Ginagan River. The bridge was wrecked. Infantry was forced to wade through gurgling water up to their armpits. At the same time entrenched Japanese on the other side unleashed machine guns and artillery. The forward echelons were forced to the ground. An anti-tank gun stood idle, its gunners clinging to flimsy cover. The company’s mortar section, which had pushed forward to clear the road, was also pinned down and unable to stir. Tanks moved into the lead. Bullets clanged against their flanks. Their guns raked the Jap strongpoints on the left of the Carigara road. The Japs countered with point-blank artillery.

One tank was hit thrice in succession. The others were neutralized: giants not built to fight in the tropics. The point commander ordered a withdrawal to avoid annihilation. Withdrawal — but how? Enemy fire marked their spot like lightning hurled down by heathen gods. Even the bravest among corpsmen would not budge; one tried and was riddled on the spot. The many wounded suffered untended.

But then a boy from Ohio deliberately accepted death to give his buddies a chance to live. (He was Private Walter F. Laule, the son of Mrs. Eleanor Laule, of 2325 Selzer Avenue, Cleveland.) The anti-tank gun whose gunners were glued to cover had been towed by a jeep. A machine gun was mounted on this jeep. Walter Laule sensed that immediate offensive fire was needed to save more men from dying. He sprang into the jeep. He threw the machine gun into action. The machine gun clattered. Laule sprayed the treetops to silence the snipers. He then brought the muzzle of his gun to ground level against the enemy battery and the automatic weapons. The machine gun’s clatter became an uninterrupted blast. Near and far the Japanese concentrated their fire on Laule. “E” Company seized the chance to disengage. As the last man reached cover a shell struck the jeep. The boy from Ohio was blown across the road. His death was instant.

While Walter Laule made his magnificent stand, the corpsmen worked with frantic haste. The wounded were whisked into a coconut grove at the base of the flanking ridge. Volunteers among the riflemen pitched in and helped. Private Edward Nickerson of Hingham, Massachusetts, came forward with litters and worked under fire to save the lives of more than a score of wounded comrades. Sergeant Stanley Lewandowski of Jersey City used his poncho to improvise a stretcher on which he dragged a hurt friend out of hell. Corpsman Karl Nyren of New ton Highland, Massachusetts, sat hunched in the path of machine gun fire and saved a soldier from bleeding to death. The man’s leg had been torn off. After he had bandaged him, Nyren looked for his stretcher. A mortar shell had destroyed it. So Nyren lifted his patient on his shoulder and trotted toward cover. A shell burst nearby. The violence of the concussion pitched the corpsman and his ward into a thicket. Nyren, too, was bleeding now. Nonetheless he stood up in agony. He picked up his legless comrade and staggered to cover.

The Division’s field artillery thundered. For an hour the cannoneers rained explosives on the Japanese bulwarks. The battalion once more pushed forward. The advance guard came to another stream — the Yapan River — and again met embittered resistance. Those Jap fighting men were not merely the remnants of the beaten Imperial Sixteenth Division; identifications taken from enemy dead showed that the troops facing the Thirty-Fourth were from a crack regiment[1] of the Thirtieth Japanese Infantry Division, brought in from Mindanao.

The skirmish line moved forward, “Easy” Company on the left, “George” Company on the right, tanks in the center. A heavy machinegun put into position to clear a stretch of road was instantly smashed by a Jap shell. On the right flank enemy machinegun nests held up “George” Company’s platoons. They fought through a palm grove raw with underbrush and often one could not see farther than two yards ahead. Platoon Ser geant Bowman, a well-liked leader of men, was pierced by bul lets and fell dead. His men screamed with rage. They stormed the nests and slew the Jap gunners.

On the left flank, “Easy” Company’s men traversed a low knoll and collided with a pillbox backed by a system of trenches. Direct cannon fire had forced the tanks to draw back. Well ahead of the company lay a squad commanded by Sergeant Edwin Wahl of Runnemede, New Jersey. That day they had pressed more than four miles through hostile countryside. But Wahl, not waiting for his company’s strength, built up his squad in a skirmish line along the Carigara road and countered enemy artillery and machine guns with Garands. He pursued the unequal fight until commanded to fall back.

At a nearby spot an automatic rifle team of three had been nailed down by a skilfull sniper in a breadfruit tree. The B.A.R. men lay in a shallow shell hole and the sniper waited for the first of them to show his head. Oh, they could finish off that sniper, they knew, by bringing their automatic rifle to bear. But then the sniper would get in at least one shot. It seemed that one of the three was scheduled to die. Eventually their problem was solved by a cook, Pruitt Letson of Rogersville, Alabama.

Earlier that day Cook Letson had been hurt by shrapnel while carrying a message for his commanding officer. The blast had knocked him unconscious. He regained his senses in the battalion aid station. The aid station was a tarpaulin stretched in a small clearing. A medic was about to dig fragments of shrapnel out of Letson’s flesh. But the messenger-cook felt fit enough to stand. He knew that his company had suffered heavily. He knew that manpower was needed at the front. “Let me go,” he said. “I’m okay.” Arriving at the front he spotted the sniper and shot him dead.

Another “Easy” Company man who refused evacuation was Sergeant Earl Prince of Cowan, Tennessee. He had been injured that morning leading an assault platoon. At the clearing station they patched him up and put him into an ambulance, hospital bound. Minutes before, he had heard an officer talk about the shortage of men in the lines. Prince climbed out of the ambulance, grinned at the corpsmen, and went on his way. He led his platoon through the remaining hours of the hot, hard day.

A tank destroyer from Cannon Company crunched to the front to deal with the strongpoint which held up “Easy” Company’s advance on the left side of the road. The uncouth-looking mount pushed up the road, its stubby gun weaving like the feeler of some monstrous beetle. At this point a slim young man jumped out of the roadside ditch. Lieutenant Mario Mozzone of Seattle guided the self-propelled mount to its target. The Japanese saw the SPM and they saw that the officer standing in the road was directing its fire. From a range of less than a hundred yards they concentrated artillery fire on the tank destroyer and machine gun blasts at the man. Horizontal pillars of red flame erupted from the muzzle of the tank-destroyer’s cannon. The 75’s shells mauled the enemy trenches. They threw the defenders into panic. They milled about from hole to hole with frenzied cries. “Easy” Company’s riflemen cheered. They stood upright behind the trunks of palms and slaughtered the confused Japs with rifle fire.

Lieutenant Mozzone waved the tank-destroyer to the rear after it had expended its ammunition. Then he waved another tank-destroyer forward to continue the shelling. It rumbled up, spewing destruction. Its commander, Sergeant Joseph Klein of the Bronx, New York, saw his shells raise fans of mud, debris and Japanese. He saw Mozzone wave his arms with wild exhilaration. Then everything seemed to dissolve in sound and flame. An enemy 77 millimeter shell squarely hit the SPM. Sergeant Klein was first to recover from the shock. The steel about him was spattered with blood. Lieutenant Mozzone writhed on the road. Klein checked his gun. It was still in order. But the tank-destroyer’s propelling mechanism had been blown to pieces.

It was late afternoon. The Japanese doubled their fire on the wrecked SPM, the road, on the line of gray-green skirmishers. They rushed fresh troops into their battered positions. “Easy” Company was cruelly mauled. Though ordered to dig in to protect the disabled tank-destroyer, the riflemen were pressed back, yielding foot after foot of muddy soil.

Sergeant Klein feared that his machine would fall into enemy hands. He must withdraw it or destroy it. He signaled to a tank to tow it out. The tank came forward and three men leaped to the road to attach a tow rope to the SPM. At this moment an other enemy shell smashed into the crippled tank-destroyer. All members of its crew were killed, except Sergeant Klein. Two of the three men at the tow rope lay dead. The sergeant from the Bronx staggered around his mount like a desolate ghost. He saw that the tracks were smashed and that the machine could not be towed. Then he went over to the tank.

“Blow her up,” he said sadly.

The tank backed off and gave the tank-destroyer the coup-de-grace.

As the companies fell back under the Japanese counter barrage, the enemy seemed to sense that his time had come. He counter attacked with waves of troops who had not before been seen in the Leyte battles. The skirmish lines shuddered under the impact. But they held.

Private Emmett Ross of Mount Pleasant, Iowa, placed a mortar into action and destroyed a Jap machine gun nest. Meanwhile, Japanese machine gun detachments striking through the jungle mounted their weapons and poured murderous flanking fire into our forward lines. A lieutenant from Gallatin, Missouri, Jack Brown, took charge of the threatened left flank. He walked around, directing fire into the enveloping force and encouraging the men. In between he helped to conduct wounded soldiers to the rear.

There lay men in the killing zone who had lost an arm or a leg. They would surely have died from loss of blood and shock but for the efforts of two jeep-driving corpsmen. Alfred L. Sloan of Joplin, Missouri, and Arthur Mendenhall of Galva, Kansas, labored to the limits of human ability. Four times they loaded their jeep with badly smashed casualties and drove them through machine gun and sniper fire to the surgeons’ tables. By nightfall these drivers sat in puddles of half-dried blood.

The companies retreated from open fields to dig in for the night on more protected ground. Among the last to go were a lieutenant and a private. The private, Vernon Thompson of Hopkinton, Iowa, noticed that one of the fallen who had been left as dead was moving. He crept forward to bring him back. The wounded man was heavy. The Iowan shed his equipment and managed to drag the other to cover. After that he went forward again to recover his things.

The lieutenant was Troy L. Stoneburner, a company commander. From dawn to dark he had led his team in its eleventh continuous day of battle. He had darted about under aimed bullets from enemy weapons, adjusting the fire of mortars, directing his company’s actions, supervising the evacuation of the wounded. He left the battle area only after the last of his men had reached the relative safety of a new perimeter. Stoneburner was killed in action.

The night again was filled with rain. Supply trucks bogged down in the quagmire of the roads. But the tractors kept moving. Along the perimeters foxholes filled with water. By midnight the rain had driven most men from the shelters they had dug. Engineers grumbled about turning the roads into canals. Feet were like sodden sponges and full of pain. The legs of many soldiers were covered with sores from knees to toes. “Jungle rot,” they called it. Resistance was low and fever rampant. The bandages of the wounded were soaked and covered with mud. Letters from home melted into pulp and bakers cursed over flour that had turned to paste.

The regiment had fared badly that day. But the enemy had fared worse.

“It was a bloody go,” commented Brigadier General Cramer. “Let’s pray to God that we don’t have to fight like that all the way.

Under cover of darkness the Japanese retreated.

There was a general alert an hour before dawn of November 1. The men ate their breakfast cold, standing in darkness and rain. There was no smoking and no lights could be shown. Few bothered to mix their coffee powder with water from their canteens. None bothered to wash. Squad leaders distributed fresh ammunition. With daylight, as the rain became a fading drizzle, the regiment stood ready to continue the attack.

The march began at 0800. Progress was rapid.

By 1100 the advancing column traversed the terrain of the past day’s battles. The roadside was littered with Japanese dead. Some lay alone and others lay in huddles. Many had no heads, no arms, no feet, victims of the Division’s field artillery. Charred pits marked the places where others had been cremated. There were many hastily abandoned emplacements. There were wrecked artillery pieces, discarded rifles, machine guns, helmets, packs, range finders, sake and rice. There was a scattering of letters and photographs among the rain puddles and the blood: pictures of Japanese soldiers in strutting poses, of Japanese soldiers with their arms around smiling Filipino girls, pictures of somber-faced parents of Japanese soldiers, pornographic pictures and others of drab-looking homes in Japan.

At one point along the road under a rain shelter there was a makeshift table on which rested little boxes wrapped in white cloth. These boxes contained the ashes of cremated Japs. Usually such boxes are sent home to Nippon to the dead soldiers’ folks who put them into the Yasukuni Shrine. In front of the white-bound boxes stood little dishes filled with rice and water — gifts of the survivors for the dead— but the rice was quickly stolen.

By 1300 the battalions entered Tunga. Tunga was a dead town. Swarms of flies and black birds hovered over Japanese cadavers. They were the only sign of life. After a brief rest, the infantry pushed on. On to Carigara and the sea.

Only at two points there was resistance. A group of pillboxes off the highway had halted the advance guard. A tank went forward and ran into trouble. A direct hit killed the tank commander. Infantry teams closed in and finished the job.

The second nest of resistance was dealt with by Sergeant Jerome T. Palmer and his squad. Palmer’s home is in Milwaukee. Barricaded behind the palm logs and a mound of earth was a lone enemy machine gun. Palmer deployed his squad in a semicircle and they approached the Japanese nest in short rushes. Two Japs were killed in the final assault. Palmer pounced on the third and caught him alive.

The prisoner asked in which manner he would be killed. “Will there be torture?” His captor laughed. The Jap was happy when he learned that he would not be tortured. He gave much information of value. He had been away from Japan for five years and he was glad to be out of the war. “We Japanese hate life in the tropics,” he said, adding, “Officers should be put in a cage to fight their wars while we soldiers look on.”

When the regiment dug in that night its forward elements were less than two miles from Carigara. There were scattered Japanese attempts to infiltrate the perimeters during the night. About the situation on the morning of November 2, the Division Record states:

“The stage was now set for the assault on Carigara, and indications were that this would be a hotly contested point. Air reconnaissance reported extensive digging, erection of barricades and similar fortifications in Carigara, and Japanese forces in the vicinity were reported from numerous sources as strong. Guerillas brought word of continuous movement of enemy troops toward Carigara from the Ormoc Valley. A battery of 75 mm guns was reported by air observers on the western outskirts of the town. Patrols of the First Cavalry Division had probed into the area and had met resistance.”

The First Cavalry Division was poised northeast of Carigara after an amphibious landing. It was determined that the attack on the coastal town should be a coordinated assault by the two divisions. With daylight the Twenty-Fourth Infantry Division’s four artillery battalions laid down a barrage which rolled from a thousand yards south of Carigara a like distance beyond it. Three thousand shells were sent on their way. The barrage stopped at 0900 and the day’s advance began.

The regiment pushed down the highway in a column of battalions. Patrols ranged ahead. “George” Company swung across country to block escape routes from Carigara to the west. From the point there came a shout: “Look! The ocean!”

Eyes lit up as they caught glimpses of the sea through gaps in the expanse of undergrown plantations. There was a bay, bright and blue and wide. Jutting headlands gleamed in the morning sun. It was like a hallucination of harmony and peace floating hard at the frontiers of the shell-torn earth. The battalions crossed three streams and halted at the outskirts of Carigara.

Off on the flank a squad of riflemen had blundered into an ambush. The Japs permitted the group to advance to within dropped to the ground, unable further to move in any direction. The enemy settled down to a man-by-man extermination of this group. A B.A.R. man from another squad went to their aid. He stood up and shouted and so drew the Japanese fire. In this manner he also spotted the location of the hostile automatic weapons. The B.A.R. man sprayed the twenty rounds in his magazine in the direction of two enemy machine guns. Then he dodged into cover to repeat his maneuver from another spot. He saved the lives of twelve men. The ambushed squad was able to withdraw. The B.A.R. man was Sam Dodds, Private, of Bonanza, Arkansas.

From somewhere Jap mortar shells fell on a platoon advancing between a palm grove and a swamp. The shelling became a barrage which covered the route of march with a checkerboard of bursts. As the platoon withdrew and swerved to circle the zone of impact, there came a shout through the hollow crashing of explosives: “Hey, you guys, don’t leave me here.”

A Chinese-American from San Francisco, Corporal Leeman Chan, saw a wounded soldier lying near the center of the pattern of explosions. Chan did not wait for a corpsman. Close to the earth he crawled into the barrage. No one expected Chan to come out alive. But he reached the wounded man and grasped his belt and dragged him to the shelter of a shallow ravine.

For more than an hour the assault battalions waited at the edge of Carigara. They waited for word that the First Cavalry was ready to break into the town from the east. No word came. The brother division had been delayed by burned bridges. The battalions then moved forward without further delay. A 180-foot bridge across the Carigara River had been destroyed by the Japanese. The crossing was difficult. Strong combat patrols pushed into the town.

Not a shot was fired as troops of the Twenty-Fourth entered Carigara. The assault companies marching through the deserted streets were ready for anything that might happen. But the streets were empty and the houses were silent hulks and there was only the distant boom of the surf. Suddenly the lively chords of “Elmer’s Tune” came prancing from a tumbledown shack by the roadside. Lead scouts broke into little jigs. Other leg-tired soldiers waltzed imaginary partners a few yards. Inside the shack, flushed and happy, was Corpsman Arthur Mendenhall whose jeep, two days earlier, had been flecked with the blood of comrades he had rescued. Mendenhall had discovered a piano.

The Division had crossed Leyte Island from coast to coast. It had won complete control of the strategic Leyte Valley and had cut the island in two. After twelve days of “hot, dirty, sweaty and bloody battling” the Japanese were in such haste to retreat into the ramparts of the Ormoc Valley that they had fairly abandoned the town of Capoocan, west of silent, smoking Carigara. Seven Japanese ammunition dumps were discovered dug into a hillside. They were full of artillery and mortar ammunition. Of the captured store of rifle ammunition many cartridges had wooden bullets.[2]

Some three thousand Japanese cadavers were counted and buried in the Division’s drive. But victory had exacted a saturnine price: among its own the Division counted one thousand and eighty-four wounded, or missing, or dead.

(Continue to Chapter 11: Ghosts of Guadalcanal)

_____________________________________________________

[1] The 41st Japanese Infantry Regiment, which landed on Leyte four days after the invasion to reinforce the defense of Carigara.

[2] At this stage of the campaign, the Division’s Twenty-First Infantry Regiment, which had hitherto operated on the southern end of Leyte, was on its way to Carigara to relieve the battle-weary Thirty-Fourth. The Japanese at this time were falling back along the single lane coastal road from Carigara to Pinamopoan. From Pinamopoan a winding trail led south over the mountains into the Ormoc Valley. This trail had been the route of Japanese reinforcements brought from Cebu, Mindanao and Luzon via Ormoc Bay. No good harbor lies west of Pinamopoan on the north coast of Leyte, and only trails lead to the scattered villages in that mountain-filled sector, later to be known as Breakneck Ridge.