Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 22 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 21: Infantry Speaking)

On the day on which Lieutenant General R. L. Eichelberger, Commanding General of the Eighth Army, officially pronounced the end of organized enemy resistance on Mindanao, we buried Colonel Thomas E. Clifford in the Division cemetery outside of Davao. The dauntless and beloved commander of the “Rock of Chickamauga,” indestructible in the ordeal on Kilay Ridge, cockily in the vanguard when we stormed Davao, never second to any man in danger, was blasted to death by a Japanese mortar shell near Tamogan. It happened days after that mountain town had been deemed secured. Diehard Japanese survivors had fired the shell from an abaca hideout. Clifford had fallen wounded in the burst. One of the colonel’s aides had rushed to the side of his fallen commander. There is a saying among soldiers that two shells never explode on the same spot. But a second Japanese shell plummeted out of the sky and burst on the spot of the first. It killed Clifford and critically wounded his aide.

Ten of us stood at Clifford’s grave in silence under the harsh sun. The chaplain’s voice was quiet and sad, and flies crawled over the olive drab blanket which was the dead leader’s casket. To his right was the grave of a sergeant from Massachusetts, to his left the grave of a private from Utah. In a husky voice, Colonel William Verbeck commanded, “Attention!” We stood like ramrods and saluted. A few days later the people of Davao celebrated the end of the war by naming their rubble-framed town plaza Clifford Square.

On that day a soldier who was the father of five children, with enough “points” to his credit to sail for home on the next ship, was blown to pieces by a Japanese mine. And three hours before the “Cease Firing ‘ order was beamed to all the corners of the Far East, seven American infantrymen were killed north of Davao by bursts of machine gun fire from ambush.

Under the palms of Talomo Beach we sat huddled under ponchos, watching a motion picture in a drizzling rain, when the performance suddenly was interrupted. An officer holding a flashlight climbed on a platform and said curtly, “We just received a radio message that the Japanese are surrendering.”

A tremendous cheer went up in the darkness of jungle and plantation. The thing that in the feeling of most of us had become malevolent eternity had abruptly come to an end. Carbines and Garands crackled in great clouds of sound. Along the outer perimeters machine guns chattered toward the sky. Men howled like dogs and crowed like cocks. Parachute flares floated beneath the clouds, whistles shrilled in the swamps, and from the abaca expanses showers of tracer bullets swished through the rain. The Japs of Mindanao, oblivious of their empire’s downfall, thought a night attack was under way and sent squalls of lead into the dripping darkness. In a palm grove south of Talomo, other Japanese soldiers clandestinely watching a Twenty-First Regiment motion picture show, suddenly decided to heave grenades into the crowd. Two Americans were killed and several wounded.

Obedience to the order to cease firing was as difficult as the reversal of an old habit. Killing Japanese on sight had become a matter of reflex and instinct. The unexpected brake applied upon the urge to kill caused slight confusion. One American soldier was murdered in a brawl with his fellows. Another was found knifed to death, apparently by a Filipino, in a fray involving a native girl. But on the morning of August 15 the situation reverted to “normal.” A company of infantry encamped near the barrio of Bunawan radioed that it was being machine gunned by a force of Japanese. A battery of field artillery went into action to disperse the attackers. Brigadier General Kenneth Cramer watched the shells whine over the abaca at two-second intervals. And before the rumble of the forty-eighth shell explosion had died away, a radio operator jumped into the air and called out: “Message! Message! End of mission. End of war.”

Cramer turned to his men and smiled. The chunky soldier-senator from Connecticut who for years had shared his riflemen’s hardships in the agonized advances and the killing, shoved his helmet back from his leathery forehead and laughed happily. “Make a note of this,” he said. “We may have heard the last shell that was fired in this war.” Thoughtfully he added: “The question is — will the Japs believe us?”

The “cease fire” order was official. Patrols were cancelled near Biao, Baguio and Tamogan. The Division’s advances among the wild foothills of Mount Apo and Mount Monoy were halted. Riflemen were ordered to capture stragglers on the dim Kibawe Trail instead of slaying them. At the road junctions detachments of military police were alerted to guide captives to the rear. But the next morning found the combat patrols again in full swing.

A “Fox” Company, Nineteenth Regiment, truck convoy was ambushed out of abaca thickets and twelve Americans were hit. “Able” Company riflemen surprised and killed twenty Japanese on the precipices of the Tamogan River. Anti-Tank Company patrols killed five. “George” Company lost nine men in a skirmish and killed eighteen Japs. Near Baguio a combat patrol surprised thirty-seven Japanese naval troops cultivating camotes and rice in a jungle clearing. There was no chance to explain that hostilities were over. All the Japs were killed. On the upper reaches of the Libuganon River a force of Japanese traveling downstream on palm-log rafts attempted to break an American river block; machine guns raked the rafts, which drifted on toward Davao Gulf, unmanned, and fifty-five dead were counted along the muddy banks. There were patrol clashes near Licanan Airdrome and along the shores of Sarangani Bay. Near Budbud and Dalliao small enemy detachments launched suicide charges in the night. There were thousands of armed Japanese roaming the mountains of Davao Province in scattered bands; they were without contact with one another, without radios, without a uniform command. There were also thousands of armed Moros and Filipino irregulars roaming the forests who blithely disregarded any order to cease firing; they went on killing any Jap for his rifle, wrist watch or boots, or if the Jap owned none of those — they killed him for revenge.

A Filipino woman, the wife of a captured Japanese officer, reported that the Japanese commander, General Harada, lay ill with malaria in an almost inaccessible canyon, tended by half-breed comfort girls and kept alive on a daily food allotment of one half handful of rice. His chief of staff, the lady reported, subsisted on boiled jungle vegetation. Meanwhile, a Davao shoe maker, Alfonso Daiparine, hung out a sign which read: “Hail to America — Hell to Japan. May the Japanese tribes decrease.” The Japanese colonists would never return to Davao; their goods and plantations would be sold to the highest bidder. In the overcrowded and bomb-battered St. Peter’s Church of Davao, Father Clovis Thibault who had just returned from years of hiding in caves read a thanksgiving mass and four thousand brown people bowed their heads and wept.

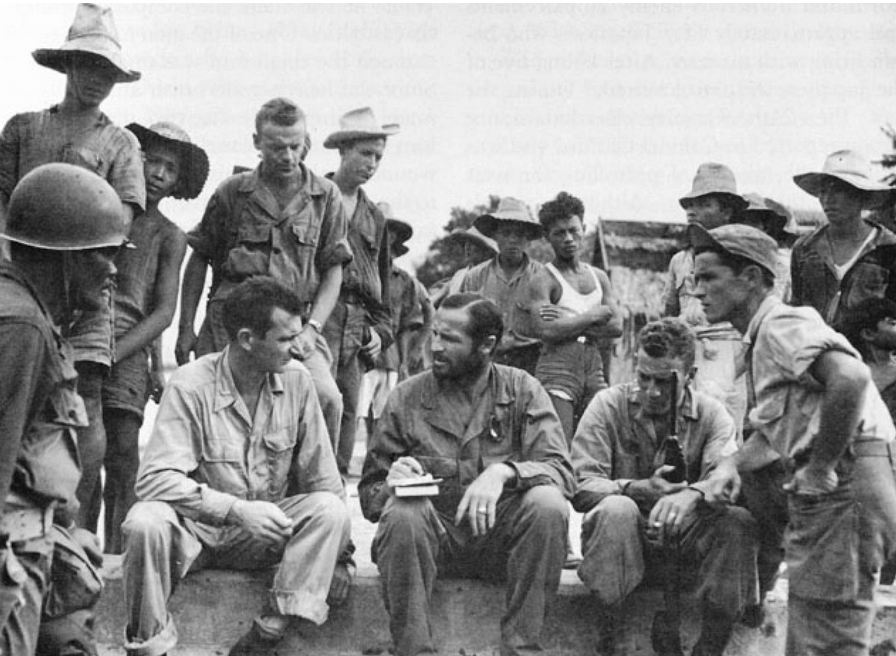

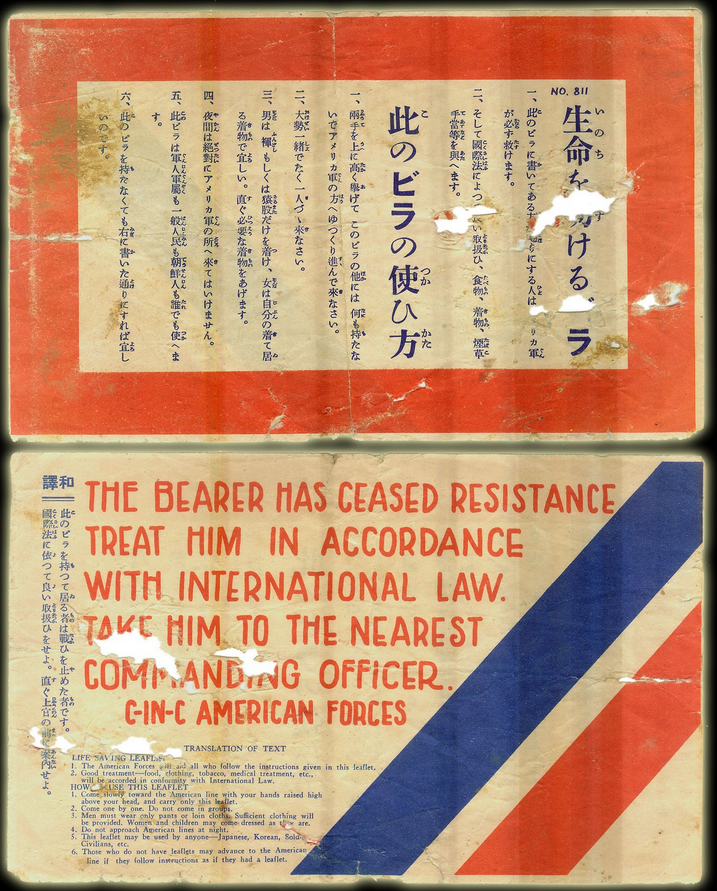

The Division’s command worked hard to convince the Japanese that the war was over. Thousands of “surrender leaflets” were dropped over the jungles by planes. Sound trucks toured the front, blaring surrender messages in Japanese. Japanese prisoners of war were released to urge their compatriots to cease resistance and emerge. The regiments established prisoner reception points at all road and trail junctions. Red arrows pointed the way. Signs in Japanese were posted along the fringes of unexplored wilderness. “Welcome Japs,” they read. “Kill and Be Killed No More.” … “Surrender Here — Fine Food, Free Transportation, No Walking.” … “Surrender Now, Safety Guaranteed.” … “Register Here for Free Trip to Nippon.”

But for days no Japs surrendered. The sound trucks met sniper fire. Released prisoners of war were killed by their uncaptured fellows. Over the Division’s Special Services radio came news of an unbridled “Victory” celebration on New York’s Times Square. Infantrymen grumbled their contempt for the distant revelers as the feeling grew along the perimeters that the Japanese would not come in. It’s over. It’s great. But rifles were still oiled and loaded on Mindanao. New graves were dug for Americans to be buried with combat boots protruding from under olive drab blankets. The killing continued sporadically for weeks after the official surrender.

Sixteen days after the capitulation of Japan, the Division commander succeeded in establishing contact with General Harada. An infantry patrol had captured a Japanese major, the former chief of the Kempei (Military Police) of Davao, who knew where the Japanese commander was hiding. Guerillas clamored for the major’s life. But General Woodruff equipped the Jap with American rations and an American radio and told him to go out and inform General Harada of the termination of hostilities. A jeep carried the messenger to the end of all roads along the upper Talomo River, but the emissary refused to plunge into the jungle alone. The major, who in his time had ordered the execution of hundreds of Filipino patriots, was afraid of crossing forests teeming with armed natives. A patrol then escorted the Jap through the guerilla zone, and after a three day trek he radioed that he had found General Harada.

Harada declared himself willing to surrender. But he asked American cooperation in informing the hundreds of lost detachments of his dispersed command. He also asked General Woodruff to build a bridge across a difficult stream west of Tamogan, for most of his men were too ill from malaria, hunger and untended wounds to ford the river. Division engineers built the bridge. Surrender orders over the Jap general’s signature were distributed by Americans. Japanese began to trickle into captivity.

It was a grim and wretched procession. Many of the enemy warriors who had fought so long and so well resembled meandering skeletons in rags. Only few had shoes. Many came in crawling on hands and knees, near death but grinning with politeness. Almost all were famished, malarious, and suffering from scrub typhus, dysentery and jungle rot. Japanese mothers surrendered, carrying dying infants. Of Davao’s estimated 19,000 Japanese civilians less than 5,000 remained alive. The jungles north of Mandog, Tamogan, and around the volcanic fastness of Mount Apo were strewn with the corpses of men, women and children who had died of hunger, disease, or under the bayonets of their own military. In a secret jungle town not far from the village of Sirib which the Japs had built with the stolen houses of Davao, one of the Division’s combat reporters found a mass of Japanese women and children whose throats had been cut from ear to ear. Natives reported that this mass murder — one of many — was performed by Japanese soldiers upon their own kin when food gave out and retreat became an agony without hope.

General Harada surrendered, together with the surviving members of his staff, including an admiral. All of them were more dead than alive, but strangely unbroken in their soldierly dignity. Yet, many of their soldiers refused to give up. Gathered in desperate little bands they marched deeper into the mountains, looting barrios on their way, killing native civilians and carrying off young women.

Toward the end of September, 1945, the Division was ordered to move into Japan. The sky over Davao Gulf was a virgin blue and the peak of Mount Apo towered purple against the azure. A hard sun flamed on the cobalt sea. The black sands of Talomo Beach teemed with bathing men. A convoy of gray transports stood in from the Pacific. Soldiers crowded the decks of the ships — young, crisp, clean soldiers, battle virgins fresh from the training camps.

The gaunt and yellowed bathers on Talomo Beach watched the newcomers land.

Someone chanted with sardonic glee: “You will be sorreee… and we are going home.”

The newcomers grinned bravely, devouring sunlight on their unrusted helmets. A veteran sergeant paddled among the anchored transports in a canoe fashioned from an airplane gasoline tank, shouting, “Welcome, welcome.”

We of the Twenty-Fourth were glad. “Christ,” was the feeling of every one of us, “I never thought I’d leave these god damned islands alive and so soon. I’m glad; hell, I’m so glad. Back home the homes will be more drab than we pictured them in our dreams, and the women won’t be as glamorous maybe as our pinups made us like to believe, but they’ll be wonderful and sweet all the same, and an honest to goodness elm or oak is worth more in our hearts than a hundred million coconut palms, and people will wear shoes and have soap to make them smell clean and everything will be whole instead of wrecked and ruined as we had to wreck and ruin these islands against our own will. Look at Mount Apo: the ugliest mountain in the world. Hell, they’ll be killing Jap stragglers in these islands ten years from now. Only hope that none of the Moros will dig up our buried buddies to steal their blankets and boots.”

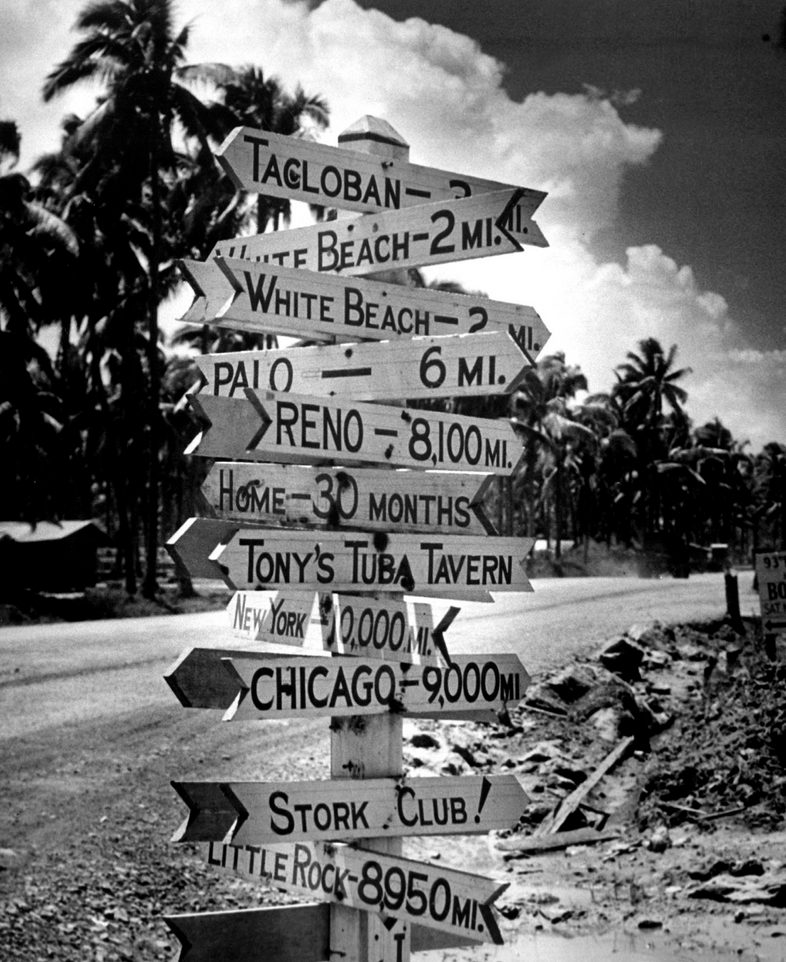

On the beach road, convoys of bullet-scarred trucks loaded replacements and then rumbled away toward the regimental bivouacs in the ocean of abaca. The newcomers who crowded the trucks wiped sweat out of their eyes and peered curiously at the hot, savage countryside. They stared at the burned houses, the graves, the decapitated palms, the wrecks of trucks and airplanes littering the roadsides, the listless and emaciated natives, and they leaned forward to decipher signs at junctions along their dusty course. “There’s Malaria in the Area,” said one sign. ‘Take Atabrine or IT Will GET YOU.” Another read: “Polluted Water, Don’t Drink from This Stream.” And another: “Keep Weapons Ready. Beware of Snipers and Explosives.” And there was a gay, freshly painted poster, red on white:

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN

GO SLOW

CAUTION

PLEASE DON’T KILL OUR REPLACEMENTS

THE END