Editor’s note: The following work by Sir Edward Shepherd Creasy is extracted from The Great Events by Famous Historians, Vol. I (published 1905). All spelling in the original.

Two thousand three hundred and forty years ago a council of Athenian officers was summoned on the slope of one of the mountains that look over the plain of Marathon, on the eastern coast of Attica. The immediate subject of their meeting was to consider whether they should give battle to an enemy that lay encamped on the shore beneath them; but on the result of their deliberations depended, not merely the fate of two armies, but the whole future progress of human civilization

There were eleven members of that council of war. Ten were the generals who were then annually elected at Athens, one for each of the local tribes into which the Athenians were divided. Each general led the men of his own tribe, and each was invested with equal military authority. But one of the archons was also associated with them in the general command of the army. This magistrate was termed the “Polemarch” or War-ruler. He had the privilege of leading the right wing of the army in battle, and his vote in a council of war was equal to that of any of the generals. A noble Athenian named Callimachus was the war-ruler of this year, and, as such, stood listening to the earnest discussion of the ten generals. They had, indeed, deep matter for anxiety, though little aware how momentous to mankind were the votes they were about to give, or how the generations to come would read with interest the record of their discussions. They saw before them the invading forces of a mighty empire, which had in the last fifty years shattered and enslaved nearly all the kingdoms and principal cities of the then known world. They knew that all the resources of their own country were comprised in the little army intrusted to their guidance. They saw before them a chosen host of the great king, sent to wreak his special wrath on that country and on the other insolent little Greek community which had dared to aid his rebels and burn the capital of one of his provinces. That victorious host had already fulfilled half its mission of vengeance.

Eretria, the confederate of Athens in the bold march against Sardis nine years before, had fallen in the last few days; and the Athenian generals could discern from the heights the island of Ægilia, in which the Persians had deposited their Eretrian prisoners, whom they had reserved to be led away captives into Upper Asia, there to hear their doom from the lips of King Darius himself. Moreover, the men of Athens knew that in the camp before them was their own banished tyrant, who was seeking to be reinstated by foreign cimeters in despotic sway over any remnant of his countrymen that might survive the sack of their town, and might be left behind as too worthless for leading away into Median bondage.

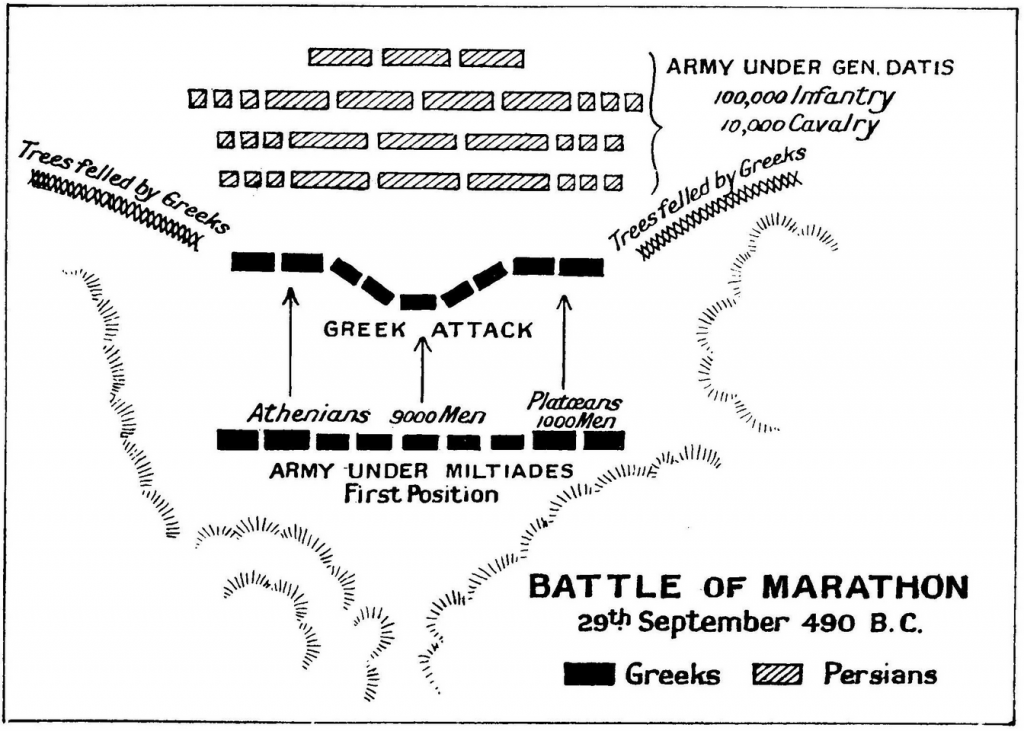

The numerical disparity between the force which the Athenian commanders had under them, and that which they were called on to encounter, was hopelessly apparent to some of the council. The historians who wrote nearest to the time of the battle do not pretend to give any detailed statements of the numbers engaged, but there are sufficient data for our making a general estimate. Every free Greek was trained to military duty; and, from the incessant border wars between the different states, few Greeks reached the age of manhood without having seen some service. But the muster-roll of free Athenian citizens of an age fit for military duty never exceeded thirty thousand, and at this, epoch probably did not amount to two-thirds of that number. Moreover, the poorer portion of these were unprovided with the equipments, and untrained to the operations of the regular infantry. Some detachments of the best-armed troops would be required to garrison the city itself and man the various fortified posts in the territory, so that it is impossible to reckon the fully equipped force that marched from Athens to Marathon, when the news of the Persian landing arrived, at higher than ten thousand men.

With one exception, the other Greeks held back from aiding them. Sparta had promised assistance, but the Persians had landed on the sixth day of the moon, and a religious scruple delayed the march of Spartan troops till the moon should have reached its full. From one quarter only, and that from a most unexpected one, did Athens receive aid at the moment of her great peril.

Some years before this time the little state of Platæa in Boeotia, being hard pressed by her powerful neighbor, Thebes, had asked the protection of Athens, and had owed to an Athe man army the rescue of her independence. Now when it was noised over Greece that the Mede had come from the uttermost parts of the earth to destroy Athens, the brave Platæans, unsolicited, marched with their whole force to assist the defence, and to share the fortunes of their benefactors.

The general levy of the Platæans amounted only to a thousand men; and this little column, marching from their city along the southern ridge of Mount Cithæron, and thence across the Attic territory, joined the Athenian forces above Marathon almost immediately before the battle. The reënforcement was numerically small, but the gallant spirit of the men who composed it must have made it of tenfold value to the Athenians, and its presence must have gone far to dispel the cheerless feeling of being deserted and friendless, which the delay of the Spartan succors was calculated to create among the Athenian ranks.

This generous daring of their weak but true-hearted ally was never forgotten at Athens. The Platæans were made the civil fellow-countrymen of the Athenians, except the right of exercising certain political functions; and from that time forth in the solemn sacrifices at Athens, the public prayers were offered up for a joint blessing from Heaven upon the Athenians, and the Platæans also.

After the junction of the column from Platæa, the Athenian commanders must have had under them about eleven thousand fully armed and disciplined infantry, and probably a large number of irregular light-armed troops; as, besides the poorer citizens who went to the field armed with javelins, cutlasses, and targets, each regular heavy-armed soldier was attended in the camp by one or more slaves, who were armed like the inferior freemen. Cavalry or archers the Athenians (on this occasion) had none, and the use in the field of military engines was not at that period introduced into ancient warfare.

Contrasted with their own scanty forces, the Greek commanders saw stretched before them, along the shores of the winding bay, the tents and shipping of the varied nations who marched to do the bidding of the king of the Eastern world. The difficulty of finding transports and of securing provisions would form the only limit to the numbers of a Persian army. Nor is there any reason to suppose the estimate of Justin exaggerated, who rates at a hundred thousand the force which on this occasion had sailed, under the satraps Datis and Artaphernes, from the Cilician shores against the devoted coasts of Euboea and Attica. And after largely deducting from this total, so as to allow for mere mariners and camp followers, there must still have remained fearful odds against the national levies of the Athenians.

Nor could Greek generals then feel that confidence in the superior quality of their troops, which ever since the battle of Marathon has animated Europeans in conflicts with Asiatics, as, for instance, in the after struggles between Greece and Persia, or when the Roman legions encountered the myriads of Mithradates and Tigranes, or as is the case in the Indian campaigns of our own regiments. On the contrary, up to the day of Marathon the Medes and Persians were reputed invincible. They had more than once met Greek troops in Asia Minor, in Cyprus, in Egypt, and had invariably beaten them.

Nothing can be stronger than the expressions used by the early Greek writers respecting the terror which the name of the Medes inspired, and the prostration of men’s spirits before the apparently resistless career of the Persian arms. It is, therefore, little to be wondered at that five of the ten Athenian generals shrank from the prospect of fighting a pitched battle against an enemy so superior in numbers and so formidable in military renown. Their own position on the heights was strong and offered great advantages to a small defending force against assailing masses. They deemed it mere foolhardiness to descend into the plain to be trampled down by the Asiatic horse, overwhelmed with the archery, or cut to pieces by the invincible veterans of Cambyses and Cyrus.

Moreover, Sparta, the great war state of Greece, had been applied to, and had promised succor to Athens, though the religious observance which the Dorians paid to certain times and seasons had for the present delayed their march. Was it not wise, at any rate, to wait till the Spartans came up, and to have the help of the best troops in Greece, before they exposed themselves to the shock of the dreaded Medes?

Specious as these reasons might appear, the other five generals were for speedier and bolder operations. And, fortunately for Athens and for the world, one of them was a man, not only of the highest military genius, but also of that energetic character which impresses its own type and ideas upon spirits feebler in conception.

Miltiades was the head of one of the noblest houses at Athens. He ranked the Æacidæ among his ancestry, and the blood of Achilles flowed in the veins of the hero of Marathon. One of his immediate ancestors had acquired the dominion of the Thracian Chersonese, and thus the family became at the same time Athenian citizens and Thracian princes. This occurred at the time when Pisistratus was tyrant of Athens. Two of the relatives of Miltiades—an uncle of the same name, and a brother named Stesagoras—had ruled the Chersonese before Miltiades became its prince. He had been brought up at Athens in the house of his father, Cimon, who was renowned throughout Greece for his victories in the Olympic chariot-races, and who must have been possessed of great wealth.

The sons of Pisistratus, who succeeded their father in the tyranny at Athens, caused Cimon to be assassinated; but they treated the young Miltiades with favor and kindness and when his brother Stesagoras died in the Chersonese, they sent him out there as lord of the principality. This was about twenty-eight years before the battle of Marathon, and it is with his arrival in the Chersonese that our first knowledge of the career and character of Miltiades commences. We find, in the first act recorded of him, the proof of the same resolute and unscrupulous spirit that marked his mature age. His brother’s authority in the principality had been shaken by war and revolt: Miltiades determined to rule more securely. On his arrival he kept close within his house, as if he was mourning for his brother. The principal men of the Chersonese, hearing of this, assembled from all the towns and districts, and went together to the house of Miltiades, on a visit of condolence. As soon as he had thus got them in his power, he made them all prisoners. He then asserted and maintained his own absolute authority in the peninsula, taking into his pay a body of five hundred regular troops, and strengthening his interest by marrying the daughter of the king of the neighboring Thracians.

When the Persian power was extended to the Hellespont and its neighborhood, Miltiades, as prince of the Chersonese, submitted to King Darius; and he was one of the numerous tributary rulers who led their contingents of men to serve in the Persian army, in the expedition against Scythia. Miltiades and the vassal Greeks of Asia Minor were left by the Persian king in charge of the bridge across the Danube, when the invading army crossed that river, and plunged into the wilds of the country that now is Russia, in vain pursuit of the ancestors of the modern Cossacks. On learning the reverses that Darius met with in the Scythian wilderness, Miltiades proposed to his companions that they should break the bridge down and leave the Persian king and his army to perish by famine and the Scythian arrows. The rulers of the Asiatic Greek cities, whom Miltiades addressed, shrank from this bold but ruthless stroke against the Persian power, and Darius returned in safety.

But it was known what advice Miltiades had given, and the vengeance of Darius was thenceforth specially directed against the man who had counselled such a deadly blow against his empire and his person. The occupation of the Persian arms in other quarters left Miltiades for some years after this in possession of the Chersonese; but it was precarious and interrupted. He, however, availed himself of the opportunity which his position gave him of conciliating the good-will of his fellow-countrymen at Athens, by conquering and placing under the Athenian authority the islands of Lemnos and Imbros, to which Athens had ancient claims, but which she had never previously been able to bring into complete subjection.

At length, in B.C. 494, the complete suppression of the Ionian revolt by the Persians left their armies and fleets at liberty to act against the enemies of the Great King to the west of the Hellespont. A strong squadron of Phoenician galleys was sent against the Chersonese. Miltiades knew that resistance was hopeless, and while the Phoenicians were at Tenedos, he loaded five galleys with all the treasure that he could collect, and sailed away for Athens. The Phoenicians fell in with him, and chased him hard along the north of the Ægean. One of his galleys, on board of which was his eldest son Metiochus, was actually captured. But Miltiades, with the other four, succeeded in reaching the friendly coast of Imbros in safety. Thence he afterward proceeded to Athens, and resumed his station as a free citizen of the Athenian commonwealth.

The Athenians, at this time, had recently expelled Hippias the son of Pisistratus, the last of their tyrants. They were in the full glow of their newly recovered liberty and equality; and the constitutional changes of Clisthenes had inflamed their republican zeal to the utmost. Miltiades had enemies at Athens; and these, availing themselves of the state of popular feeling, brought him to trial for his life for having been tyrant of the Chersonese. The charge did not necessarily import any acts of cruelty or wrong to individuals: it was founded on no specific law; but it was based on the horror with which the Greeks of that age regarded every man who made himself arbitrary master of his fellow-men, and exercised irresponsible dominion over them.

The fact of Miltiades having so ruled in the Chersonese was undeniable; but the question which the Athenians assembled in judgment must have tried, was whether Miltiades, although tyrant of the Chersonese, deserved punishment as an Athenian citizen. The eminent service that he had done the state in conquering Lemnos and Imbros for it, pleaded strongly in his favor. The people refused to convict him. He stood high in public opinion. And when the coming invasion of the Persians was known, the people wisely elected him one of their generals for the year.

Two other men of high eminence in history, though their renown was achieved at a later period than that of Miltiades, were also among the ten Athenian generals at Marathon. One was Themistocles, the future founder of the Athenian navy, and the destined victor of Salamis. The other was Aristides, who afterward led the Athenian troops at Platæa, and whose integrity and just popularity acquired for his country, when the Persians had finally been repulsed, the advantageous preëminence of being acknowledged by half of the Greeks as their imperial leader and protector. It is not recorded what part either Themistocles or Aristides took in the debate of the council of war at Marathon. But, from the character of Themistocles, his boldness, and his intuitive genius for extemporizing the best measures in every emergency—a quality which the greatest of historians ascribes to him beyond all his contemporaries—we may well believe that the vote of Themistocles was for prompt and decisive action. On the vote of Aristides it may be more difficult to speculate. His predilection for the Spartans may have made him wish to wait till they came up; but, though circumspect, he was neither timid as a soldier nor as a politician, and the bold advice of Miltiades may probably have found in Aristides a willing, most assuredly it found in him a candid, hearer.

Miltiades felt no hesitation, as to the course which the Athenian army ought to pursue; and earnestly did he press his opinion on his brother generals. Practically acquainted with the organization of the Persian armies, Miltiades felt convinced of the superiority of the Greek troops, if properly handled; he saw with the military eye of a great general the advantage which the position of the forces gave him for a sudden attack, and as a profound politician he felt the perils of remaining inactive, and of giving treachery time to ruin the Athenian cause.

One officer in the council of war had not yet voted. This was Callimachus, the War-ruler. The votes of the generals were five and five, so that the voice of Callimachus would be decisive.

On that vote, in all human probability, the destiny of all the nations of the world depended. Miltiades turned to him, and in simple soldierly eloquence—the substance of which we may read faithfully reported in Herodotus, who had conversed with the veterans of Marathon—the great Athenian thus adjured his countrymen to vote for giving battle:

“It now rests with you, Callimachus, either to enslave Athens, or, by assuring her freedom, to win yourself an immortality of fame, such as not even Harmodius and Aristogiton have acquired; for never, since the Athenians were a people, were they in such danger as they are in at this moment. If they bow the knee to these Medes, they are to be given up to Hippias, and you know what they then will have to suffer. But if Athens comes victorious out of this contest, she has it in her to become the first city of Greece. Your vote is to decide whether we are to join battle or not. If we do not bring on a battle presently, some factious intrigue will disunite the Athenians, and the city will be betrayed to the Medes. But if we fight, before there is anything rotten in the state of Athens, I believe that, provided the gods will give fair play and no favor, we are able to get the best of it in an engagement.”

The vote of the brave War-ruler was gained, the council determined to give battle; and such was the ascendancy and acknowledged military eminence of Miltiades, that his brother generals one and all gave up their days of command to him, and cheerfully acted under his orders. Fearful, however, of creating any jealousy, and of so failing to obtain the vigorous coöperation of all parts of his small army, Miltiades waited till the day when the chief command would have come round to him in regular rotation before he led the troops against the enemy.

The inaction of the Asiatic commanders during this interval appears strange at first sight; but Hippias was with them, and they and he were aware of their chance of a bloodless conquest through the machinations of his partisans among the Athenians. The nature of the ground also explains in many points the tactics of the opposite generals before the battle, as well as the operations of the troops during the engagement.

The plain of Marathon, which is about twenty-two miles distant from Athens, lies along the bay of the same name on the north-eastern coast of Attica. The plain is nearly in the form of a crescent, and about six miles in length. It is about two miles broad in the centre, where the space between the mountains and the sea is greatest, but it narrows toward either extremity, the mountains coming close clown to the water at the horns of the bay. There is a valley trending inward from the middle of the plain, and a ravine comes down to it to the southward. Elsewhere it is closely girt round on the land side by rugged limestone mountains, which are thickly studded with pines, olive-trees and cedars, and overgrown with the myrtle, arbutus, and the other low odoriferous shrubs that everywhere perfume the Attic air.

The level of the ground is now varied by the mound raised over those who fell in the battle, but it was an unbroken plain when the Persians encamped on it. There are marshes at each end, which are dry in spring and summer and then offer no obstruction to the horseman, but are commonly flooded with rain and so rendered impracticable for cavalry in the autumn, the time of year at which the action took place.

The Greeks, lying encamped on the mountains, could watch every movement of the Persians on the plain below, while they were enabled completely to mask their own. Miltiades also had, from, his position, the power of giving battle whenever he pleased, or of delaying it at his discretion, unless Datis were to attempt the perilous operation of storming the heights.

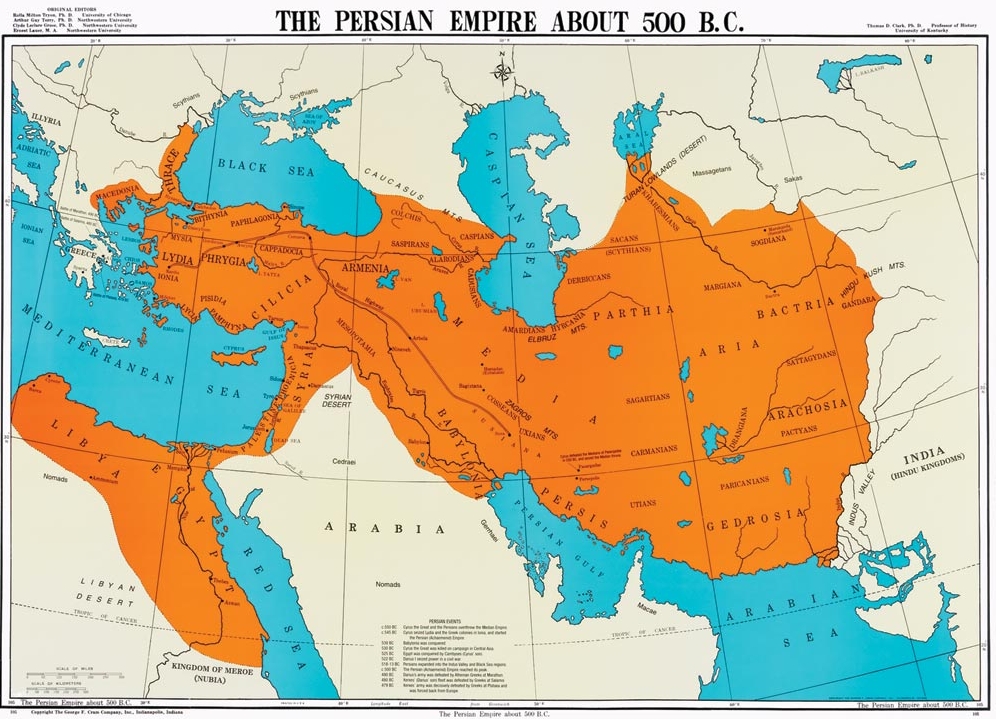

If we turn to the map of the Old World, to test the comparative territorial resources of the two states whose armies were now about to come into conflict, the immense preponderance of the material power of the Persian king over that of the Athenian republic is more striking than any similar contrast which history can supply. It has been truly remarked that, in estimating mere areas Attica, containing on its whole surface only seven hundred square miles, shrinks into insignificance if compared with many a baronial fief of the Middle Ages, or many a colonial allotment of modern times. Its antagonist, the Persian, empire, comprised the whole of modern Asiatic and much of modern European Turkey, the modern kingdom of Persia and the countries of modern Georgia, Armenia, Balkh, the Punjaub, Afghanistan, Beloochistan, Egypt and Tripoli.

Nor could a European, in the beginning of the fifth century before our era, look upon this huge accumulation of power beneath the sceptre of a single Asiatic ruler with the indifference with which we now observe on the map the extensive dominions of modern Oriental sovereigns; for, as has been already remarked, before Marathon was fought, the prestige of success and of supposed superiority of race was on the side of the Asiatic against the European. Asia was the original seat of human societies, and long before any trace can be found of the inhabitants of the rest of the world having emerged from the rudest barbarism, we can perceive that mighty and brilliant empires flourished in the Asiatic continent. They appear before us through the twilight of primeval history, dim and indistinct, but massive and majestic, like mountains in the early dawn.

Instead, however, of the infinite variety and restless change which has characterized the institutions and fortunes of European states ever since the commencement of the civilization of our continent, a monotonous uniformity pervades the histories of nearly all Oriental empires, from the most ancient down to the most recent times. They are characterized by the rapidity of their early conquests, by the immense extent of the dominions comprised in them, by the establishment of a satrap or pashaw system of governing the provinces, by an invariable and speedy degeneracy in the princes of the royal house, the effeminate nurslings of the seraglio succeeding to the warrior sovereigns reared in the camp, and by the internal anarchy and insurrections which indicate and accelerate the decline and fall of these unwieldy and ill-organized fabrics of power.

It is also a striking fact that the governments of all the great Asiatic empires have in all ages been absolute despotisms. And Heeren is right in connecting this with another great fact, which is important from its influence both on the political and the social life of Asiatics. “Among all the considerable nations of Inner Asia, the paternal government of every household was corrupted by polygamy: where that custom exists, a good political constitution is impossible. Fathers, being converted into domestic despots, are ready to pay the same abject obedience to their sovereign which they exact from their family and dependents in their domestic economy.”

We should bear in mind, also, the inseparable connection between the state religion and all legislation which has always prevailed in the East, and the constant existence of a powerful sacerdotal body, exercising some check, though precarious and irregular, over the throne itself, grasping at all civil administration, claiming the supreme control of education, stereotyping the lines in which literature and science must move, and limiting the extent to which it shall be lawful for the human mind to prosecute its inquiries.

With these general characteristics rightly felt and understood it becomes a comparatively easy task to investigate and appreciate the origin, progress and principles of Oriental empires in general, as well as of the Persian monarchy in particular. And we are thus better enabled to appreciate the repulse which Greece gave to the arms of the East, and to judge of the probable consequences to human civilization, if the Persians had succeeded in bringing Europe under their yoke, as they had already subjugated the fairest portions of the rest of the then known world.

The Greeks, from their geographical position, formed the natural van-guard of European liberty against Persian ambition; and they preëminently displayed the salient points of distinctive national character which have rendered European civilization so far superior to Asiatic. The nations that dwelt in ancient times around and near the northern shores of the Mediterranean Sea were the first in our continent to receive from the East the rudiments of art and literature, and the germs of social and political organizations. Of these nations the Greeks, through their vicinity to Asia Minor, Phoenicia, and Egypt, were among the very foremost in acquiring the principles and habits of civilized life; and they also at once imparted a new and wholly original stamp on all which they received. Thus, in their religion, they received from foreign settlers the names of all their deities and many of their rites, but they discarded the loathsome monstrosities of the Nile, the Orontes, and the Ganges; they nationalized their creed, and their own poets created their beautiful mythology. No sacerdotal caste ever existed in Greece.

So, in their governments, they lived long under hereditary kings, but never endured the permanent establishment of absolute monarchy. Their early kings were constitutional rulers, governing with defined prerogatives. And long before the Persian invasion, the kingly form of government had given way in almost all the Greek states to republican institutions, presenting infinite varieties of the blending or the alternate predominance of the oligarchical and democratical principles. In literature and science the Greek intellect followed no beaten track, and acknowledged no limitary rules. The Greeks thought their subjects boldly out; and the novelty of a speculation invested it in their minds with interest, and not with criminality.

Versatile, restless, enterprising, and self-confident, the Greeks presented the most striking contrast to the habitual quietude and submissiveness of the Orientals; and, of all the Greeks, the Athenians exhibited these national characteristics in the strongest degree. This spirit of activity and daring, joined to a generous sympathy for the fate of their fellow-Greeks in Asia, had led them to join in the last Ionian war, and now mingling with their abhorrence of the usurping family of their own citizens, which for a period had forcibly seized on and exercised despotic power at Athens, nerved them to defy the wrath of King Darius, and to refuse to receive back at his bidding the tyrant whom they had some years before driven out.

The enterprise and genius of an Englishman have lately confirmed by fresh evidence, and invested with fresh interest, the might of the Persian monarch who sent his troops to combat at Marathon. Inscriptions in a character termed the Arrow-headed, or Cuneiform, had long been known to exist on the marble monuments at Persepolis, near the site of the ancient Susa, and on the faces of rocks in other places formerly ruled over by the early Persian kings. But for thousands of years they had been mere unintelligible enigmas to the curious but baffled beholder; and they were often referred to as instances of the folly of human pride, which could indeed write its own praises in the solid rock, but only for the rock to outlive the language as well as the memory of the vainglorious inscribers.

The elder Niebuhr, Grotefend, and Lassen, had made some guesses at the meaning of the cuneiform letters; but Major Rawlinson of the East India Company’s service, after years of labor, has at last accomplished the glorious achievement of fully revealing the alphabet and the grammar of this long unknown tongue. He has, in particular, fully deciphered and expounded the inscription on the sacred rock of Behistun, on the western frontiers of Media. These records of the Achæmenidæ have at length found their interpreter; and Darius himself speaks to us from the consecrated mountain, and tells us the names of the nations that obeyed him, the revolts that he suppressed, his victories, his piety, and his glory.

Kings who thus seek the admiration of posterity are little likely to dim the record of their successes by the mention of their occasional defeats; and it throws no suspicion on the narrative of the Greek historians that we find these inscriptions silent respecting the overthrow of Datis and Artaphernes, as well as respecting the reverses which Darius sustained in person during his Scythian campaigns. But these indisputable monuments of Persian fame confirm, and even increase the opinion with which Herodotus inspires us of the vast power which Cyrus founded and Cambyses increased; which Darius augmented by Indian and Arabian conquests, and seemed likely, when he directed his arms against Europe, to make the predominant monarchy of the world.

With the exception of the Chinese empire, in which, throughout all ages down to the last few years, one-third of the human race has dwelt almost unconnected with the other portions, all the great kingdoms, which we know to have existed in ancient Asia, were, in Darius’ time, blended into the Persian. The northern Indians, the Assyrians, the Syrians, the Babylonians, the Chaldees, the Phoenicians, the nations of Palestine, the Armenians, the Bactrians, the Lydians, the Phrygians, the Parthians, and the Medes, all obeyed the sceptre of the Great King: the Medes standing next to the native Persians in honor, and the empire being frequently spoken of as that of the Medes, or as that of the Medes and Persians. Egypt and Cyrene were Persian provinces; the Greek colonists in Asia Minor and the islands of the Ægean were Darius’ subjects; and their gallant but unsuccessful attempts to throw off the Persian yoke had only served to rivet it more strongly, and to increase the general belief that the Greeks could not stand before the Persians in a field of battle. Darius’ Scythian war, though unsuccessful in its immediate object, had brought about the subjugation of Thrace and the submission of Macedonia. From the Indus to the Peneus, all was his.

We may imagine the wrath with which the lord of so many nations must have heard, nine years before the battle of Marathon, that a strange nation toward the setting sun, called the Athenians, had dared to help his rebels in Ionia against him, and that they had plundered and burned the capital of one of his provinces. Before the burning of Sardis, Darius seems never to have heard of the existence of Athens; but his satraps in Asia Minor had for some time seen Athenian refugees at their provincial courts imploring assistance against their fellow-countrymen.

When Hippias was driven away from Athens, and the tyrannic dynasty of the Pisistratidæ finally overthrown in B.C. 510, the banished tyrant and his adherents, after vainly seeking to be restored by Spartan intervention, had betaken themselves to Sardis, the capital city of the satrapy of Artaphernes. There Hippias—in the expressive words of Herodotus—began every kind of agitation, slandering the Athenians before Artaphernes, and doing all he could to induce the satrap to place Athens in subjection to him, as the tributary vassal of King Darius. When the Athenians heard of his practices, they sent envoys to Sardis to remonstrate with the Persians against taking up the quarrel of the Athenian refugees.

But Artaphernes gave them in reply a menacing command to receive Hippias back again if they looked for safety. The Athenians were resolved not to purchase safety at such a price, and after rejecting the satrap’s terms, they considered that they and the Persians were declared enemies. At this very crisis the Ionian Greeks implored the assistance of their European brethren, to enable them to recover their independence from Persia. Athens, and the city of Eretria in Euboea, alone consented. Twenty Athenian galleys, and five Eretrian, crossed the Ægean Sea, and by a bold and sudden march upon Sardis, the Athenians and their allies succeeded in capturing the capital city of the haughty satrap who had recently menaced them with servitude or destruction. They were pursued, and defeated on their return to the coast, and Athens took no further part in the Ionian war; but the insult that she had put upon the Persian power was speedily made known throughout that empire, and was never to be forgiven or forgotten.

In the emphatic simplicity of the narrative of Herodotus, the wrath of the Great King is thus described: “Now when it was told to King Darius that Sardis had been taken and burned by the Athenians and Ionians, he took small heed of the Ionians, well knowing who they were, and that their revolt would soon be put down; but he asked who, and what manner of men, the Athenians were. And when he had been told, he called for his bow; and, having taken it, and placed an arrow on the string, he let the arrow fly toward heaven; and as he shot it into the air, he said, ‘Oh! supreme God, grant me that I may avenge myself on the Athenians,’ And when he had said this, he appointed one of his servants to say to him every day as he sat at meat, ‘Sire, remember the Athenians.'”

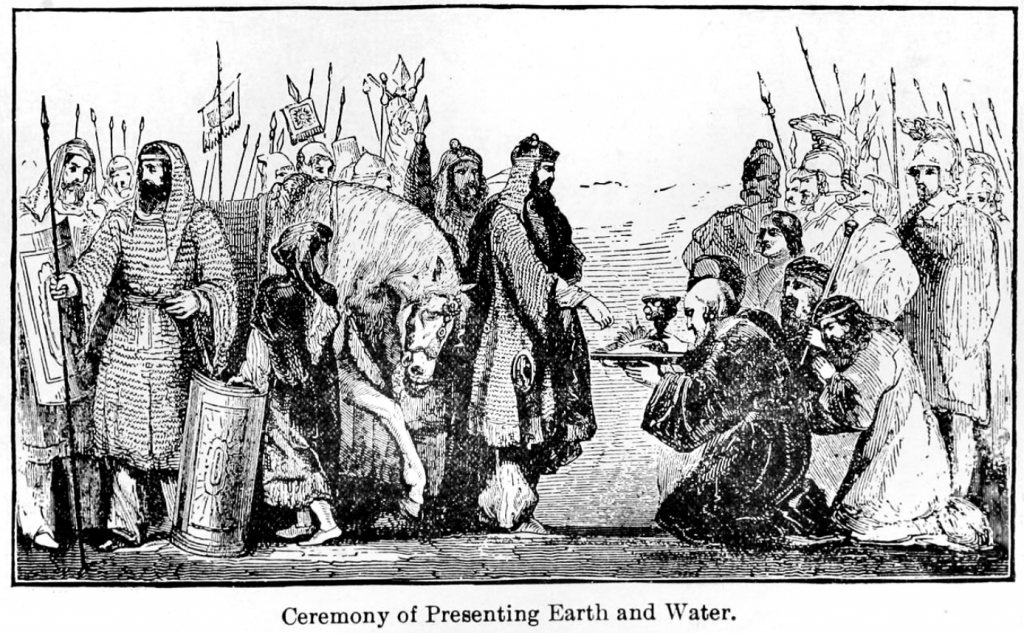

Some years were occupied in the complete reduction of Ionia. But when this was effected, Darius ordered his victorious forces to proceed to punish Athens and Eretria, and to conquer European Greece, The first armament sent for this purpose was shattered by shipwreck, and nearly destroyed off Mount Athos. But the purpose of King Darius was not easily shaken, A larger army was ordered to be collected in Cilicia, and requisitions were sent to all the maritime cities of the Persian empire for ships of war, and for transports of sufficient size for carrying cavalry as well as infantry across the Ægean. While these preparations were being made, Darius sent heralds round to the Grecian cities demanding their submission to Persia. It was proclaimed in the market-place of each little Hellenic state—some with territories not larger than the Isle of Wight—that King Darius, the lord of all men, from the rising to the setting sun, required earth and water to be delivered to his heralds, as a symbolical acknowledgment that he was head and master of the country. Terror-stricken at the power of Persia and at the severe punishment that had recently been inflicted on the refractory Ionians, many of the continental Greeks and nearly all the islanders submitted, and gave the required tokens of vassalage. At Sparta and Athens an indignant refusal was returned—a refusal which was disgraced by outrage and violence against the persons of the Asiatic heralds.

Fresh fuel was thus added to the anger of Darius against Athens, and the Persian preparations went on with renewed vigor. In the summer of B.C. 490, the army destined for the invasion was assembled in the Aleian plain of Cilicia, near the sea. A fleet of six hundred galleys and numerous transports was collected on the coast for the embarkation of troops, horse as well as foot. A Median general named Datis, and Artaphernes, the son of the satrap of Sardis, and who was also nephew of Darius, were placed in titular joint-command of the expedition. The real supreme authority was probably given to Datis alone, from the way in which the Greek writers speak of him.

We know no details of the previous career of this officer; but there is every reason to believe that his abilities and bravery had been proved by experience, or his Median birth would have prevented his being placed in high command by Darius. He appears to have been the first Mede who was thus trusted by the Persian kings after the overthrow of the conspiracy of the Median magi against the Persians immediately before Darius obtained the throne. Datis received instructions to complete the subjugation of Greece, and especial orders were given him with regard to Eretria and Athens. He was to take these two cities, and he was to lead the inhabitants away captive, and bring them as slaves into the presence of the Great King.

Datis embarked his forces in the fleet that awaited them, and coasting along the shores of Asia Minor till he was off Samos, he thence sailed due westward through the Ægean Sea for Greece, taking the islands in his way. The Naxians had, ten years before, successfully stood a siege against a Persian armament, but they now were too terrified to offer any resistance, and fled to the mountain tops, while the enemy burned their town and laid waste their lands. Thence Datis, compelling the Greek islanders to join him with their ships and men, sailed onward to the coast of Eubœa. The little town of Carystus essayed resistance, but was quickly overpowered.

He next attacked Eretria. The Athenians sent four thousand men to its aid; but treachery was at work among the Eretrians; and the Athenian force received timely warning from one of the leading men of the city to retire to aid in saving their own country, instead of remaining to share in the inevitable destruction of Eretria. Left to themselves, the Eretrians repulsed the assaults of the Persians against their walls for six days; on the seventh they were betrayed by two of their chiefs, and the Persians occupied the city. The temples were burned in revenge for the firing of Sardis, and the inhabitants were bound, and placed as prisoners in the neighboring islet of Ægilia, to wait there till Datis should bring the Athenians to join them in captivity, when both populations were to be led into Upper Asia, there to learn their doom from the lips of King Darius himself.

Flushed with success, and with half his mission thus accomplished, Datis reëmbarked his troops, and, crossing the little channel that separates Eubœa from the mainland, he encamped his troops on the Attic coast at Marathon, drawing up his galleys on the shelving beach, as was the custom with the navies of antiquity. The conquered islands behind him served as places of deposit for his provisions and military stores. His position at Marathon seemed to him in every respect advantageous, and the level nature of the ground on which he camped was favorable for the employment of his cavalry, if the Athenians should venture to engage him. Hippias, who accompanied him, and acted as the guide of the invaders, had pointed out Marathon as the best place for a landing, for this very reason. Probably Hippias was also influenced by the recollection that forty-seven years previously, he, with his father Pisistratus, had crossed with an army from Eretria to Marathon, and had won an easy victory over their Athenian enemies on that very plain, which had restored them to tyrannic power. The omen seemed cheering. The place was the same, but Hippias soon learned to his cost how great a change had come over the spirit of the Athenians.

But though “the fierce democracy” of Athens was zealous and true against foreign invader and domestic tyrant, a faction existed in Athens, as at Eretria, who were willing to purchase a party triumph over their fellow-citizens at the price of their country’s ruin. Communications were opened between these men and the Persian camp, which would have led to a catastrophe like that of Eretria, if Miltiades had not resolved and persuaded his colleagues to resolve on fighting at all hazards.

When Miltiades arrayed his men for action, he staked on the arbitrament of one battle not only the fate of Athens, but that of all Greece; for if Athens had fallen, no other Greek state, except Lacedæmon, would have had the courage to resist; and the Lacedæmonians, though they would probably have died in their ranks to the last man, never could have successfully resisted the victorious Persians and the numerous Greek troops which would have soon marched under the Persian satraps, had they prevailed over Athens.

Nor was there any power to the westward of Greece that could have offered an effectual opposition to Persia, had she once conquered Greece, and made that country a basis for future military operations. Rome was at this time in her season of utmost weakness. Her dynasty of powerful Etruscan kings had been driven out; and her infant commonwealth was reeling under the attacks of the Etruscans and Volscians from without, and the fierce dissensions between the patricians and plebeians within. Etruria, with her lucumos and serfs, was no match for Persia. Samnium had not grown into the might which she afterward put forth; nor could the Greek colonies in South Italy and Sicily hope to conquer when their parent states had perished. Carthage had escaped the Persian yoke in the time of Cambyses, through the reluctance of the Phoenician mariners to serve against their kinsmen.

But such forbearance could not long have been relied on, and the future rival of Rome would have become as submissive a minister of the Persian power as were the Phoenician cities themselves. If we turn to Spain; or if we pass the great mountain chain, which, prolonged through the Pyrenees, the Cevennes, the Alps, and the Balkan, divides Northern from Southern Europe, we shall find nothing at that period but mere savage Finns, Celts, Slavs, and Teutons. Had Persia beaten Athens at Marathon, she could have found no obstacle to prevent Darius, the chosen servant of Ormuzd, from advancing his sway over all the known Western races of mankind. The infant energies of Europe would have been trodden out beneath universal conquest, and the history of the world, like the history of Asia, have become a mere record of the rise and fall of despotic dynasties, of the incursions of barbarous hordes, and of the mental and political prostration of millions beneath the diadem, the tiara, and the sword.

Great as the preponderance of the Persian over the Athenian power at that crisis seems to have been, it would be unjust to impute wild rashness to the policy of Miltiades and those who voted with him in the Athenian council of war, or to look on the after-current of events as the mere fortunate result of successful folly. As before has been remarked, Miltiades, while prince of the Chersonese, had seen service in the Persian armies; and he knew by personal observation how many elements of weakness lurked beneath their imposing aspect of strength. He knew that the bulk of their troops no longer consisted of the hardy shepherds and mountaineers from Persia proper and Kurdistan, who won Cyrus’s battles; but that unwilling contingents from conquered nations now filled up the Persian muster-rolls, fighting more from compulsion than from any zeal in the cause of their masters. He had also the sagacity and the spirit to appreciate the superiority of the Greek armor and organization over the Asiatic, notwithstanding former reverses. Above all, he felt and worthily trusted the enthusiasm of those whom he led.

The Athenians whom he led had proved by their newborn valor in recent wars against the neighboring states that “liberty and equality of civic rights are brave spirit-stirring things, and they, who, while under the yoke of a despot, had been no better men of war than any of their neighbors, as soon as they were free, became the foremost men of all; for each felt that in fighting for a free commonwealth, he fought for himself, and whatever he took in hand, he was zealous to do the work thoroughly,” So the nearly contemporaneous historian describes the change of spirit that was seen in the Athenians after their tyrants were expelled; and Miltiades knew that in leading them against the invading army, where they had Hippias, the foe they most hated, before them, he was bringing into battle no ordinary men, and could calculate on no ordinary heroism.

As for traitors, he was sure that, whatever treachery might lurk among some of the higher born and wealthier Athenians, the rank and file whom he commanded were ready to do their utmost in his and their own cause. With regard to future attacks from Asia, he might reasonably hope that one victory would inspirit all Greece to combine against the common foe; and that the latent seeds of revolt and disunion in the Persian empire would soon burst forth and paralyze its energies, so as to leave Greek independence secure.

With these hopes and risks, Miltiades, on the afternoon of a September day, B.C. 490, gave the word for the Athenian army to prepare for battle. There were many local associations connected with those mountain heights which were calculated powerfully to excite the spirits of the men, and of which the commanders well knew how to avail themselves in their exhortations to their troops before the encounter. Marathon itself was a region sacred to Hercules. Close to them was the fountain of Macaria, who had in days of yore devoted herself to death for the liberty of her people. The very plain on which they were to fight was the scene of the exploits of their national hero, Theseus; and there, too, as old legends told, the Athenians and the Heraclidæ had routed the invader, Eurystheus.

These traditions were not mere cloudy myths or idle fictions, but matters of implicit earnest faith to the men of that day, and many a fervent prayer arose from the Athenian ranks to the heroic spirits who, while on earth, had striven and suffered on that very spot, and who were believed to be now heavenly powers, looking down with interest on their still beloved country, and capable of interposing with superhuman aid in its behalf.

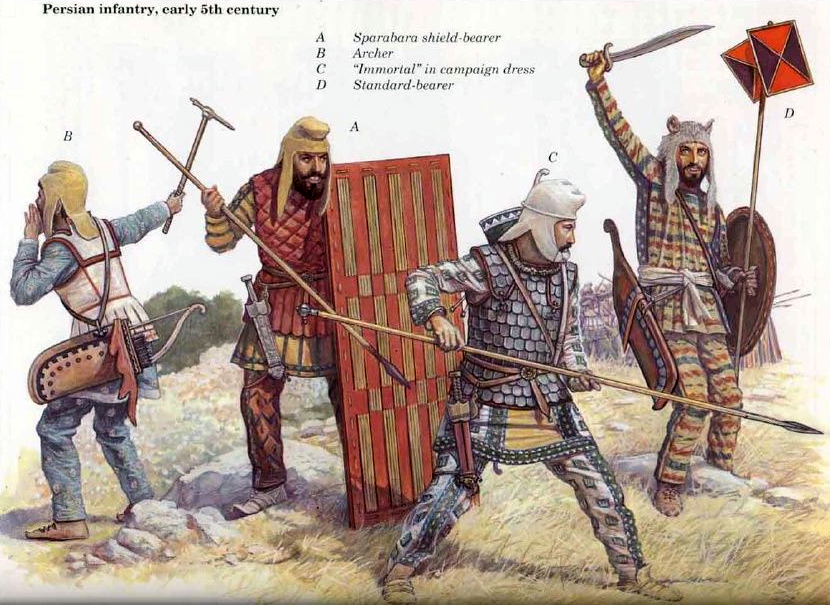

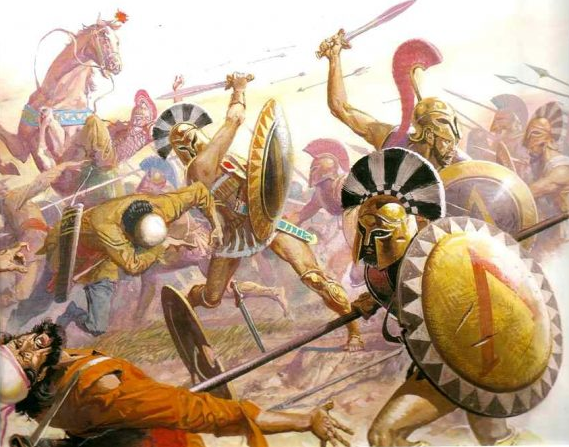

According to old national custom, the warriors of each tribe were arrayed together; neighbor thus fighting by the side of neighbor, friend by friend, and the spirit of emulation and the consciousness of responsibility excited to the very utmost. The War-ruler, Callimachus, had the leading of the right wing; the Platæans formed the extreme left; and Themistocles and Aristides commanded the centre. The line consisted of the heavy-armed spearmen only; for the Greeks—until the time of Iphicrates—took little or no account of light-armed soldiers in a pitched battle, using them only in skirmishes, or for the pursuit of a defeated enemy. The panoply of the regular infantry consisted of a long spear, of a shield, helmet, breastplate, greaves, and short sword.

Thus equipped, they usually advanced slowly and steadily into action in a uniform phalanx of about eight spears deep. But the military genius of Miltiades led him to deviate on this occasion from the commonplace tactics of his countrymen. It was essential for him to extend his line so as to cover all the practicable ground, and to secure himself from being outflanked and charged in the rear by the Persian horse. This extension involved the weakening of his line. Instead of a uniform reduction of its strength, he determined on detaching principally from his centre, which, from the nature of the ground, would have the best opportunities for rallying, if broken; and on strengthening his wings so as to insure advantage at those points; and he trusted to his own skill and to his soldiers’ discipline for the improvement of that advantage into decisive victory.

In this order, and availing himself probably of the inequalities of the ground, so as to conceal his preparations from the enemy till the last possible moment, Miltiades drew up the eleven thousand infantry whose spears were to decide this crisis in the struggle between the European and the Asiatic worlds. The sacrifices by which the favor of heaven was sought, and its will consulted, were announced to show propitious omens. The trumpet sounded for action, and, chanting the hymn of battle, the little army bore down upon the host of the foe. Then, too, along the mountain slopes of Marathon must have resounded the mutual exhortation which Æschylus, who fought in both battles, tells us was afterward heard over the waves of Salamis: “On, sons of the Greeks! Strike for the freedom of your country! strike for the freedom of your children and of your wives—for the shrines of your fathers’ gods, and for the sepulchres of your sires. All—all are now staked upon the strife.”

Instead of advancing at the usual slow pace of the phalanx, Miltiades brought his men on at a run. They were all trained in the exercise of the palæstra, so that there was no fear of their ending the charge in breathless exhaustion; and it was of the deepest importance for him to traverse as rapidly as possible the mile or so of level ground that lay between the mountain foot and the Persian outposts, and so to get his troops into close action before the Asiatic cavalry could mount, form, and manoeuvre against him, or their archers keep him long under fire, and before the enemy’s generals could fairly deploy their masses.

“When the Persians,” says Herodotus, “saw the Athenians running down on them, without horse or bowmen, and scanty in numbers, they thought them a set of madmen rushing upon certain destruction.” They began, however, to prepare to receive them, and the Eastern chiefs arrayed, as quickly as time and place allowed, the varied races who served in their motley ranks. Mountaineers from Hyrcania and Afghanistan, wild horsemen from the steppes of Khorassan, the black archers of Ethiopia, swordsmen from the banks of the Indus, the Oxus, the Euphrates and the Nile, made ready against the enemies of the Great King.

But no national cause inspired them except the division of native Persians; and in the large host there was no uniformity of language, creed, race or military system. Still, among them there were many gallant men, under a veteran general; they were familiarized with victory, and in contemptuous confidence their infantry, which alone had time to form, awaited the Athenian charge. On came the Greeks, with one unwavering line of leveled spears, against which the light targets, the short lances and cimeters of the Orientals offered weak defence. The front rank of the Asiatics must have gone down to a man at the first shock. Still they recoiled not, but strove by individual gallantry and by the weight of numbers to make up for the disadvantages of weapons and tactics, and to bear back the shallow line of the Europeans. In the centre, where the native Persians and the Sacæ fought, they succeeded in breaking through the weakened part of the Athenian phalanx; and the tribes led by Aristides and Themistocles were, after a brave resistance, driven back over the plain, and chased by the Persians up the valley toward the inner country. There the nature of the ground gave the opportunity of rallying and renewing the struggle.

Meanwhile, the Greek wings, where Miltiades had concentrated his chief strength, had routed the Asiatics opposed to them; and the Athenian and Platæan officers, instead of pursuing the fugitives, kept their troops well in hand, and, wheeling round, they formed the two wings together. Miltiades instantly led them against the Persian centre, which had hitherto been triumphant, but which now fell back, and prepared to encounter these new and unexpected assailants. Aristides and Themistocles renewed the fight with their reorganized troops, and the full force of the Greeks was brought into close action with the Persian and Sacean divisions of the enemy. Datis’ veterans strove hard to keep their ground, and evening was approaching before the stern encounter was decided.

But the Persians, with their slight wicker shields, destitute of body armor, and never taught by training to keep the even front and act with the regular movement of the Greek infantry, fought at heavy disadvantage with their shorter and feebler weapons against the compact array of well-armed Athenian and Platæan spearmen, all perfectly drilled to perform each necessary evolution in concert, and to preserve a uniform and unwavering line in battle. In personal courage and in bodily activity the Persians were not inferior to their adversaries. Their spirits were not yet cowed by the recollection of former defeats; and they lavished their lives freely, rather than forfeit the fame which they had won by so many victories. While their rear ranks poured an incessant shower of arrows over the heads of their comrades, the foremost Persians kept rushing forward, sometimes singly, sometimes in desperate groups of ten or twelve, upon the projecting spears of the Greeks, striving to force a lane into the phalanx, and to bring their cimeters and daggers into play. But the Greeks felt their superiority, and though the fatigue of the long-continued action told heavily on their inferior numbers, the sight of the carnage that they dealt upon their assailants nerved them to fight still more fiercely on.

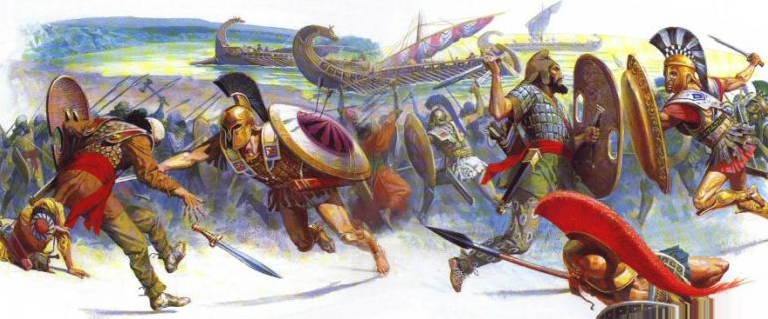

At last the previously unvanquished lords of Asia turned their backs and fled, and the Greeks followed, striking them down, to the water’s edge, where the invaders were now hastily launching their galleys, and seeking to embark and fly. Flushed with success, the Athenians attacked and strove to fire the fleet. But here the Asiatics resisted desperately, and the principal loss sustained by the Greeks was in the assault on the ships. Here fell the brave War-ruler Callimachus, the general Stesilaus, and other Athenians of note. Seven galleys were fired; but the Persians succeeded in saving the rest. They pushed off from the fatal shore; but even here the skill of Datis did not desert him, and he sailed round to the western coast of Attica, in hopes to find the city unprotected, and to gain possession of it from some of the partisans of Hippias.

Miltiades, however, saw and counteracted his manoeuvre. Leaving Aristides, and the troops of his tribe, to guard the spoil and the slain, the Athenian commander led his conquering army by a rapid night-march back across the country to Athens. And when the Persian fleet had doubled the Cape of Sunium and sailed up to the Athenian harbor in the morning, Datis saw arrayed on the heights above the city the troops before whom his men had fled on the preceding evening. All hope of further conquest in Europe for the time was abandoned, and the baffled armada returned to the Asiatic coasts.

After the battle had been fought, but while the dead bodies were yet on the ground, the promised reënforcement from Sparta arrived. Two thousand Lacedæmonian spearmen, starting immediately after the full moon, had marched the hundred and fifty miles between Athens and Sparta in the wonderfully short time of three days. Though too late to share in the glory of the action, they requested to be allowed to march to the battle-field to behold the Medes. They proceeded thither, gazed on the dead bodies of the invaders, and then praising the Athenians and what they had done, they returned to Lacedæmon.

The number of the Persian dead was sixty-four hundred; of the Athenians, one hundred and ninety-two. The number of the Platæans who fell is not mentioned; but, as they fought in the part of the army which was not broken, it cannot have been large.

The apparent disproportion between the losses of the two armies is not surprising when we remember the armor of the Greek spearmen, and the impossibility of heavy slaughter being inflicted by sword or lance on troops so armed, as long as they kept firm in their ranks.

The Athenian slain were buried on the field of battle. This was contrary to the usual custom, according to which the bones of all who fell fighting for their country in each year were deposited in a public sepulchre in the suburb of Athens called the “Ceramicus.” But it was felt that a distinction ought to be made in the funeral honors paid to the men of Marathon, even as their merit had been distinguished over that of all other Athenians. A lofty mound was raised on the plain of Marathon, beneath which the remains of the men of Athens who fell in the battle were deposited. Ten columns were erected on the spot, one for each of the Athenian tribes; and on the monumental column of each tribe were graven the names of those of its members whose glory it was to have fallen in the great battle of liberation. The antiquarian Pausanias read those names there six hundred years after the time when they were first graven. The columns have long perished, but the mound still marks the spot where the noblest heroes of antiquity repose.

A separate tumulus was raised over the bodies of the slain Platæans, and another over the light-armed slaves who had taken part and had fallen in the battle. There was also a separate funeral monument to the general to whose genius the victory was mainly due. Miltiades did not live long after his achievement at Marathon, but he lived long enough to experience a lamentable reverse of his popularity and success. As soon as the Persians had quitted the western coasts of the Ægean, he proposed to an assembly of the Athenian people that they should fit out seventy galleys, with a proportionate force of soldiers and military stores, and place it at his disposal; not telling them whither he meant to lead it, but promising them that if they would equip the force he asked for, and give him discretionary powers, he would lead it to a land where there was gold in abundance to be won with ease.

The Greeks of that time believed in the existence of eastern realms teeming with gold, as firmly as the Europeans of the sixteenth century believed in El Dorado of the West. The Athenians probably thought that the recent victor of Marathon, and former officer of Darius, was about to lead them on a secret expedition against some wealthy and unprotected cities of treasure in the Persian dominions. The armament was voted and equipped, and sailed eastward from Attica, no one but Miltiades knowing its destination until the Greek isle of paros was reached, when his true object appeared. In former years, while connected with the Persians as prince of the Chersonese, Miltiades had been involved in a quarrel with one of the leading men among the Parians, who had injured his credit and caused some slights to be put upon him at the court of the Persian satrap Hydarnes. The feud had ever since rankled in the heart of the Athenian chief, and he now attacked Paros for the sake of avenging himself on his ancient enemy.

His pretext, as general of the Athenians, was, that the Parians had aided the armament, of Datis with a war-galley. The Parians pretended to treat about terms of surrender, but used the time which they thus gained in repairing the defective parts of the fortifications of their city, and they then set the Athenians at defiance. So far, says Herodotus, the accounts of all the Greeks agree. But the Parians in after years told also a wild legend, how a captive priestess of a Parian temple of the Deities of the Earth promised Miltiades to give him the means of capturing Paros; how, at her bidding, the Athenian general went alone at night and forced his way into a holy shrine, near the city gate, but with what purpose it was not known; how a supernatural awe came over him, and in his flight he fell and fractured his leg; how an oracle afterward forbade the Parians to punish the sacrilegious and traitorous priestess, “because it was fated that Miltiades should come to an ill end, and she was only the instrument to lead, him to evil.” Such was the tale that Herodotus heard at Paros. Certain it was that Miltiades either dislocated or broke his leg during an unsuccessful siege of the city, and returned home in evil plight with his baffled and defeated forces.

The indignation of the Athenians was proportionate to the hope and excitement which his promises had raised. Xanthippas, the head of one of the first families in Athens, indicted him before the supreme popular tribunal for the capital offence of having deceived the people. His guilt was undeniable, and the Athenians passed their verdict accordingly. But the recollections of Lemnos and Marathon, and the sight of the fallen general, who lay stretched on a couch before them, pleaded successfully in mitigation of punishment, and the sentence was commuted from death to a fine of fifty talents. This was paid by his son, the afterward illustrious Cimon, Miltiades dying, soon after the trial, of the injury which he had received at Paros.

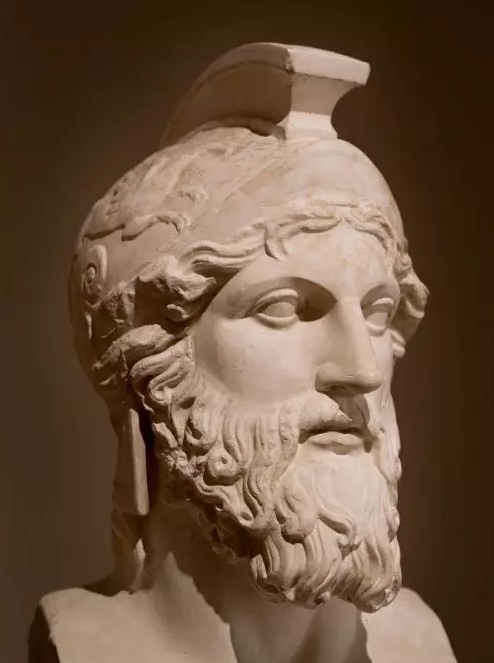

The melancholy end of Miltiades, after his elevation to such a height of power and glory, must often have been recalled to the minds of the ancient Greeks by the sight of one in particular of the memorials of the great battle which he won. This was the remarkable statue—minutely described by Pausanias—which the Athenians, in the time of Pericles, caused to be hewn out of a huge block of marble, which, it was believed, had been provided by Datis, to form a trophy of the anticipated victory of the Persians. Phidias fashioned out of this a colossal image of the goddess Nemesis, the deity whose peculiar function was to visit the exuberant prosperity both of nations and individuals with sudden and awful reverses. This statue was placed in a temple of the goddess at Rhamnus, about eight miles from Marathon. Athens itself contained numerous memorials of her primary great victory. Panenus, the cousin of Phidias, represented it in fresco on the walls of the painted porch; and, centuries afterward, the figures of Miltiades and Callimachus at the head of the Athenians were conspicuous in the fresco. The tutelary deities were exhibited taking part in the fray. In the background were seen the Phoenician galleys, and, nearer to the spectator, the Athenians and the Platæans—distinguished by their leather helmets—were chasing routed Asiatics into the marshes and the sea. The battle was sculptured also on the Temple of Victory in the Acropolis, and even now there may be traced on the frieze the figures of the Persian combatants with their lunar shields, their bows and quivers, their curved cimeters, their loose trousers, and Phrygian tiaras.

These and other memorials of Marathon were the produce of the meridian age of Athenian intellectual splendor, of the age of Phidias and Pericles; for it was not merely by the generation whom the battle liberated from Hippias and the Medes that the transcendent importance of their victory was gratefully recognized. Through the whole epoch of her prosperity, through the long Olympiads of her decay, through centuries after her fall, Athens looked back on the day of Marathon as the brightest of her national existence.

By a natural blending of patriotic pride with grateful piety, the very spirits of the Athenians who fell at Marathon were deified by their countrymen. The inhabitants of the district of Marathon paid religious rites to them, and orators solemnly invoked them in their most impassioned adjurations before the assembled men of Athens. “Nothing was omitted that could keep alive the remembrance of a deed which had first taught the Athenian people to know its own strength, by measuring it with the power which had subdued the greater part of the known world. The consciousness thus awakened fixed its character, its station, and its destiny; it was the spring of its later great actions and ambitious enterprises.”

It was not indeed by one defeat, however signal, that the pride of Persia could be broken, and her dreams of universal empire dispelled. Ten years afterward she renewed her attempts upon Europe on a grander scale of enterprise, and was repulsed by Greece with greater and reiterated loss. Larger forces and heavier slaughter than had been seen at Marathon signalized the conflicts of Greeks and Persians at Artemisium, Salamis, Platæa, and the Eurymedon. But, mighty and momentous as these battles were, they rank not with Marathon in importance. They originated no new impulse. They turned back no current of fate. They were merely confirmatory of the already existing bias which Marathon had created. The day of Marathon is the critical epoch in the history of the two nations. It broke forever the spell of Persian invincibility, which had previously paralyzed men’s minds. It generated among the Greeks the spirit which beat back Xerxes, and afterward led on Xenophon, Agesilaus, and Alexander, in terrible retaliation through their Asiatic campaigns. It secured for mankind the intellectual treasures of Athens, the growth of free institutions, the liberal enlightenment of the Western world, and the gradual ascendency for many ages of the great principles of European civilization.

A great and noble story. One of my children’s favorite bed-time stories. And driving to the store stories. And after-breakfast stories.

And it is for the loyal, brave, daring, numerically small but indomitable of spirit people of Platea that my future culture of Col Lag and First Sergeant Reel, the Plateans, are named. The classics never get old. Just older 🙂

Oh, one other thing. The Spartans were praying at their festival to Pan to give aid to the the Athenians. When the Greeks charged and started to burn the Persian ships, the invaders…. PANICKED. Get it – PANicked? That is the actual origin / root of the word; they thought their pegan God struck fear and confusion and a mindless dread into their harts.