Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Ten Great Events in History, by James Johonnot (published 1887).

After the destruction of the Roman Empire all Europe was in a state of anarchy. The long domination of Rome, and the general acceptance of the Roman idea that “the state is everything and the individual man nothing,” had unfitted the people for self-government. While Rome fell, the system of Rome, leading to absolute monarchy, persisted, and out of it grew the present governments of Europe. The conquering Goths brought in a modifying condition which changed the whole relations of monarch to people. In their social and political relations chieftains of tribes or clans divided power with the monarch, and for many centuries there was continuous warfare between these antagonistic ideas. This period is known as the “dark ages,” for while it lasted there was little visible progress, and an apparent almost entire forgetfulness of the ancient civilizations.

During the dark ages roving bands of freebooters wandered about from place to place, engaged in robbery, rapine, and murder. To resist this systematic plunder the people placed themselves under the guardianship of some powerful chieftain in the vicinity, and paid a certain amount of their earnings for the privilege of enjoying the remainder. Hence there grew up, in the Gothic communities of Europe, that peculiar state of society known as “the feudal system.” A great chieftain or lord lived in a strong castle built for defense against neighboring lords. A retinue of soldiers was in immediate attendance, who, when not engaged in war, passed their time in hunting and debauchery. All the expenses and waste of the castle and its occupants were defrayed by the peasants who cultivated the lands, and who were all obliged to take up arms whenever their lord’s dominions were invaded.

In process of time the taxes upon the people became so burdensome that they were reduced to the condition of serfs, when all their earnings, except enough to supply the barest necessaries of life, were taken from them in the shape of taxes and rents. A constantly increasing number were yearly taken from the ranks of the industrious to swell the numbers of the soldiery, until Europe seemed one vast camp.

The feudal system demanded little in the way of industry except agriculture and rude home manufactures to furnish food and clothing. Arms were purchased from other lands, the best being obtained from the higher civilization of the Moslems; but, as population increased, people began to congregate in centers and towns, and cities sprung up. These called for more varied industries, and a class of people soon became numerous who had little or no dependence upon the feudal lord. To protect themselves, craftsmen engaged in the same kind of work united and formed guilds, and the various guilds, though often warring with each other, united for the common defense. The leaders of the guilds gradually became the heads of notable burgher families who became influential and wealthy. As the cities became powerful the feudal system declined, and in many regions the powerful burghers were able to maintain their independence, not only against their old lords, but also against the monarch who ruled many lordships.

Between the monarch and the lords there was a natural antagonism—the monarch endeavoring to gain power, and the lords endeavoring to retain their privileges. The burghers made use of these contending forces; and by sometimes siding with the one and sometimes with the other, they not only secured their own freedom, but laid the foundation for the freedom of the people which is now generally recognized, and which forms the very corner-stone of our republican institutions.

But the rise of the burgher class, and the evolution of human liberty through their work, was by no means an easy task. As the military spirit was dominant, the calling of an artisan was considered derogatory, and lords and soldiers looked down upon the industrious classes as inferior beings. Scott well represents this spirit in the speech of Rob Roy, the Highland chief, in his reply to the offer of Bailie Jarvie to get his sons employment in a factory: “Make my sons weavers! I would see every loom in Glasgow, beam, treadle, and shuttles, burnt in hell-fire sooner!” To break the force of the strong military power, and to secure to the industrious classes the rights of human beings, required a continuous warfare which lasted through many centuries, and which is far from being finished at the present time. But, thanks to the sturdy valor of the burghers of the middle ages, human liberty was maintained and transmitted to succeeding generations.

Hitherto in the history of the world mountains had been found necessary for the preservation of human liberty. Thermopylæ, Morgarten, Bannockburn, were all fought where precipitous hill-sides and narrow valleys prevented the champions of freedom from being overwhelmed by numbers, and where a single man in defense of his home could wield more power than ten men in attack. The tyrants who lorded it over plains had learned by dear experience to shun mountains and avoid collisions with mountaineers; and, in case of controversies, they always endeavored to gain by stratagem what they could not obtain by force. Austrian tyranny had dashed itself in vain against the Alps, and English tyranny had turned back southward, thwarted and impotent, from the Scotch Highlands.

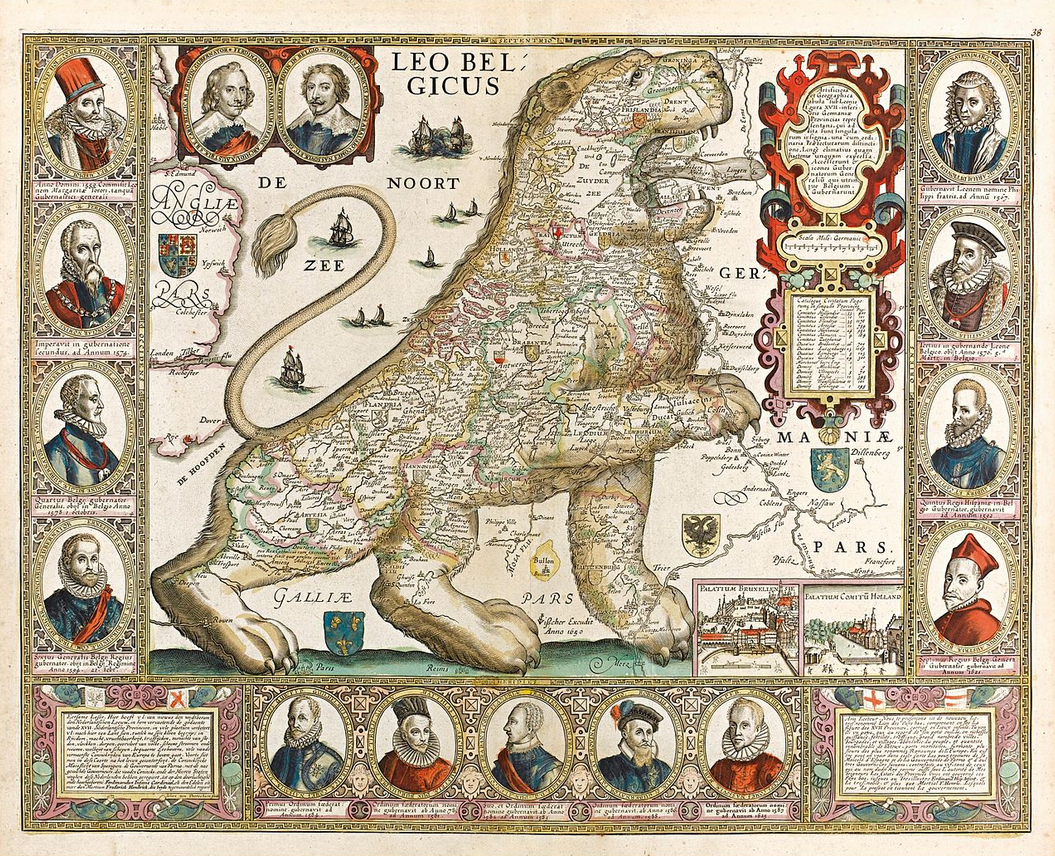

But it was to be demonstrated that liberty might have a home in other than mountain fastnesses. Along the North Sea is a stretch of country redeemed from the ocean. Great dikes, faced with granite from Norway, withstand the tempest from the turbulent ocean, and smaller dikes prevent inundations from rivers. In thousands of square miles the only land above sea-level is the summit of the dikes. In the polders or hollow places below the sea, and saved from destruction only by the dikes, is some of the richest and most productive land in Europe. Here prospered a teeming and industrious population. Agriculture, the parent of national prosperity, flourished as nowhere else. Manufactures and trade had followed in its train, until the hollow lands had become the beehive of Europe. The direction of the most vast commercial enterprises had been transferred from the lagoons of Venice to the cities of the dikes.

This country for centuries had constituted a part of the German Empire. At one side of the great lines of communication, and moored so far out to sea, it had been overlooked and neglected to a certain degree by the reigning dynasties; and out of this neglect grew its prosperity. While the rule of the central government was nearly nominal, the feudal lords never obtained a strong foothold in the country, and the order and peace of the communities were preserved by municipal officers chosen by suffrage. In process of time wealthy burgher families fairly divided political influence with princes, acid dictated a policy at once wise and humane. Extortioners were suppressed, industries fostered, and peace maintained.

In the religious controversies which followed the preaching of Luther, the eastern provinces of the hollow land almost exclusively espoused the new religion, while the western provinces clung as tenaciously to the old. While this difference in religious opinions gave rise to disputes, and tended toward the disruption of social relations, for many years toleration was practiced and peace preserved.

During the reign of Charles V as emperor of Germany, the lowland countries were permitted to go on in their career of prosperity, with the exception of a religious persecution. Charles was a bigot, and, for a time, he tried to put down heresy with a strong hand; but, finding the new doctrines firmly established in the hearts of the people, he relaxed his persecutions, and permitted things to take pretty much their own course.

Had to look up in the references about the “granite from Norway”. That was a fairly old development, after the interesting case of the naval shipworm wrecked its havoc. Anyhow, very good start, sir. Interested to see where this one reads to. The flooding of the polders as a defense mechanism has always been a interesting topic for the growth and defense of Holland.