Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Warfare By Land and Sea: Our Debt to Greece and Rome, by Eugene S. McCartney (published 1923).

The modern idea that the general is first and foremost the intellectual leader of the army is so well established that it is hard to realize that it is an evolution from an origin far different. The Greek word for general is strategos, ‘one who leads the army;’ the old Latin word is praetor, ‘one who goes before.’ From the etymologies one would suspect that the ideal general was the man qualified to set his army an example in courage and prowess. And such the history of war shows him to have been. It is not surprising that Plutarch should make the observation that from the earliest times the soldiers thought that man best fitted to rule who was most valiant in feats of arms.

How strong the conception of physical leadership was will be recognized more clearly if we recall the names of a few of the many generals who were casualties on the field of battle. The Athenian Cleon was slain in retreating from the fight at Amphipolis (422 B.C.), and his victorious opponent, Brasidas, was fatally wounded; Cleombrotus was mortally wounded at Leuctra (371 B.C.); Epaminondas died shortly after the battle of Mantinea (362 B.C.) from a spear wound he received in the breast while heading the charge, pike in hand; Philip was wounded at Chaeronea (338 B.C.); Agis was slain at Megalopolis (331 B.C.); at the third Battle of Mantinea (207 B.C.), Philopoemen completed his victory by personally slaying his opponent, Machanidas. The Persian prince Cyrus was killed at the head of his combined Persian and Greek army.

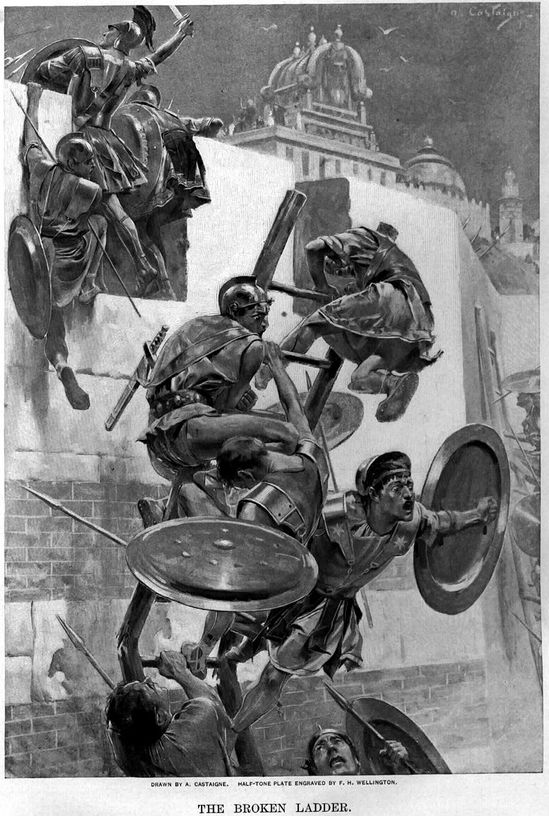

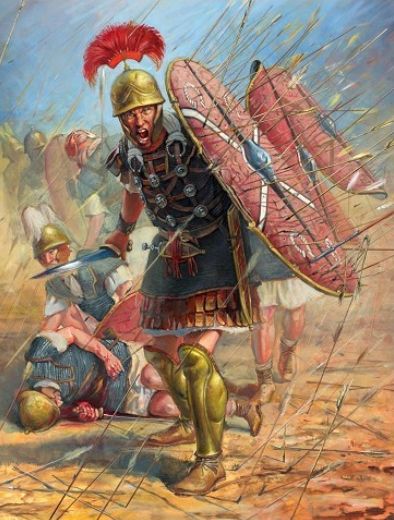

In quelling a mutiny among his soldiers, Alexander boasted that he could show wound for wound with the bravest and still have some to spare. Plutarch gives a long list of injuries inflicted upon Alexander by mace, scimitar, sword, arrow, dart and spear. In the attack on the city of the Malli Alexander personally led one of the storming parties. Impatient with the progress of events, he seized one of the first two scaling ladders to arrive and led the way up. When with only three companions he had reached the top of the wall, the ladders broke with the weight of the Macedonians hurrying to his assistance. Not heeding the entreaties of his men who implored him to jump down into their arms, Alexander with his companions leaped down on the inside. Fighting desperately, he had his corselet pierced by an arrow that penetrated a lung. When it seemed that nothing could save him, his men arrived and rescued him. Thanks to a good constitution and robust health, the young king recovered.

This hair-breadth escape emboldened Alexander’s officers to protest against his risking his life in dare-devil feats, but it was neither his nature nor policy to direct engagements from a position in the rear. As one writer puts it: “Napoleon used his sword once as generalissimo; Alexander was first in a breach, first in a charge, wounded a dozen times, himself the leader of every desperate expedition. Half of it was mad recklessness, the other was set purpose; professional armies were new as yet, and the machine needed animating with a personal feeling, if it were to submit to the labours which Alexander designed for its endurance.”[1]

The killing of Alexander at either Issus or Arbela would have meant the destruction of the Macedonians, yet without the inspiration of his magnetic presence and prowess in the front line, it is hard to see how these battles could have been won. Armies were not yet ready for solely intellectual leadership.

If chivalry in war ever existed, it was among the Greeks, and in the days of the Trojan War, when champions fought openly and prided themselves upon taking no unfair advantage. Homeric notions about the proprieties of battle died hard. When the Spartan Archidamus saw a dart from a machine of war that had just been brought from Sicily, he exclaimed: “O Hercules, the valor of man is at an end.” On the eve of the Battle of Arbela, Alexander rejected the proposal to attack by night, declaring that he would not steal a victory.

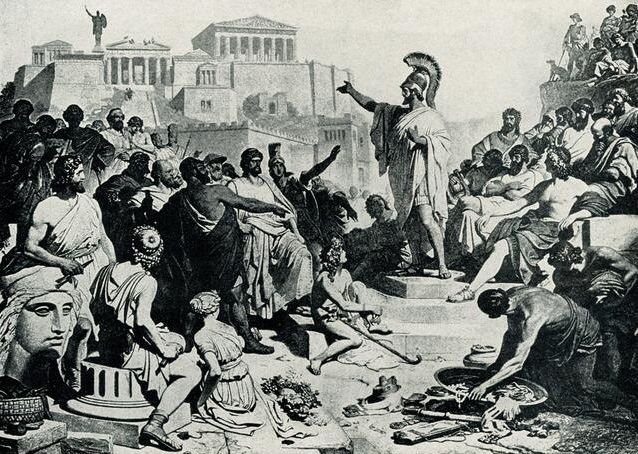

The Athenians especially took pride in the display of valor. In the funeral speech of Pericles eulogizing those who had fallen in the first year of the Peloponnesian War, we find set forth with pride a policy that seems to us to be suicidal: “In the study of war also we differ from our enemies in the following respects. We throw our city open to all, and never, by the expulsion of strangers, exclude any one from either learning or observing things, by seeing which unconcealed any of our enemies might gain an advantage; for we trust not so much to preparations and stratagems, as to our own valor for daring deeds.”

Not even in Hellenistic days was there general recognition regarding the commander’s proper part in a battle. In Polybius we find a significant sentence apropos of the battle of Mantinea in 207 B.C.: “And now there occurred an undoubted instance of what some doubt, namely, that the issues in war are for the most part decided by the skill or want of skill of the commanders.” In making his plans for the battle, Philopoemen had shown wonderful foresight, and it was only his precautionary measures that enabled him to convert into victory an apparently overwhelming disaster.

Perhaps no Greek had a clearer conception of the intellectual side of generalship than Philopoemen. Of him Livy writes that when he came to a place that was difficult of passage, he would, when alone, ask himself, or if accompanied, his companions, what measures should be taken if the enemy appeared in front, on the flank, or in the rear. These and other questions he used to ask.

Napoleon knew Livy well, and one of his maxims of war sounds strangely familiar: “A general-in-chief should ask himself frequently in the day, ‘What would I do if the enemy’s army appeared now in my front, or on my right, or my left?’ If he have any difficulty in answering these questions, his position is bad, and he should seek to remedy it.”

The Romans, too, seem to have had a real Homeric code of fighting. With them, war was a sort of duel (bellum<duellum), a personal encounter in which the most valiant won. For the commander who stripped off the armor of the opposing commander-in-chief whom he had vanquished in single combat, there was the reward of the spolia opima, ‘the richest spoils.’ This honor was gained but three times, although champions at times represented the contesting armies, notably in the case of the Horatii and Curiatii. Titus Manlius Torquatus and Marcus Valerius Corvinus gained both fame and cognomina by defeating in single combat Gauls of huge stature. During the Spanish campaigns Scipio deliberated whether he should accept the challenge of a Gaul to single combat. Marcellus never declined a challenge and always succeeded in killing his opponents.

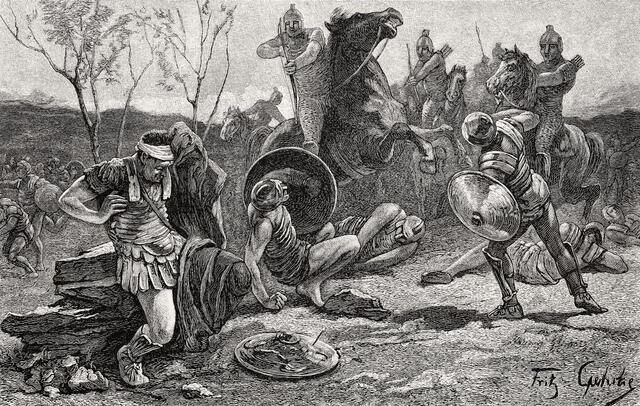

Among the Romans for centuries we find the idea of personal leadership very pronounced. In the Second Punic War, many Roman consuls met a tragic end. Flaminius, Aemilius Paulus, and Marcellus were among those who perished. Publius Cornelius Scipio, the father of the destined conqueror of Hannibal, was carried wounded from the battle of the Ticinus (219 B.C.).

At one time the Romans seem to have looked upon strategy as base deceit or treachery. In connection with the story of the refusal of the Roman senate to treat with victorious Pyrrhus, we are told that the Romans placed their dependence on heroism, and not on ruses or plotting. Even Caesar, when he found it necessary to abandon the investment of Pompey’s army at Dyrracheum, imperative as it was for him to steal a march upon his foe, still made it a point of honor (or pride?) to sound the signal for retreat by a blast of the trumpet. There is a significant passage in Livy, in which the historian of Rome’s greatness makes it a point of national pride that the Romans did not employ the stratagems of the Carthaginians, or the wiliness of the Greeks of that period, among whom, says our author, it was more glorious to outwit a foe than to vanquish him with main strength.

Rome’s arch enemies in this war well understood the province of the general. Polybius tells us that, at the battle of Metaurus, Hasdrubal regarded his personal safety as of the highest importance until all was lost. Then he faced his fate, and died a death worthy of the lion’s brood, the sons of Barca.

Their first real insight into generalship was acquired by the Romans during the Second Punic War. When Hannibal was addressing the men who were to form an ambuscade for a flank attack upon the Romans at Trebia (218 B.C.), he said: “You have an enemy blind to such arts of war.”

After their defeat in this engagement and the colossal disaster at Lake Trasimenus (217 B.C.), they began to sense the reason for continued Carthaginian success. Subsequent to the debacle at Cannae they had a wholesome respect for this new factor in warfare. Thereafter they paid it many a tacit compliment. Though they themselves had much better fighting material than the Carthaginians, time after time they allowed Hannibal with but a fraction of their own numbers to march without a fight up and down Italy and to pass by their armies almost unmolested. The Romans saw that they must take lessons from Hannibal. Under his instruction the Roman generals, especially Claudius Nero and the younger Scipio, began to execute movements they would never have dreamed of otherwise.

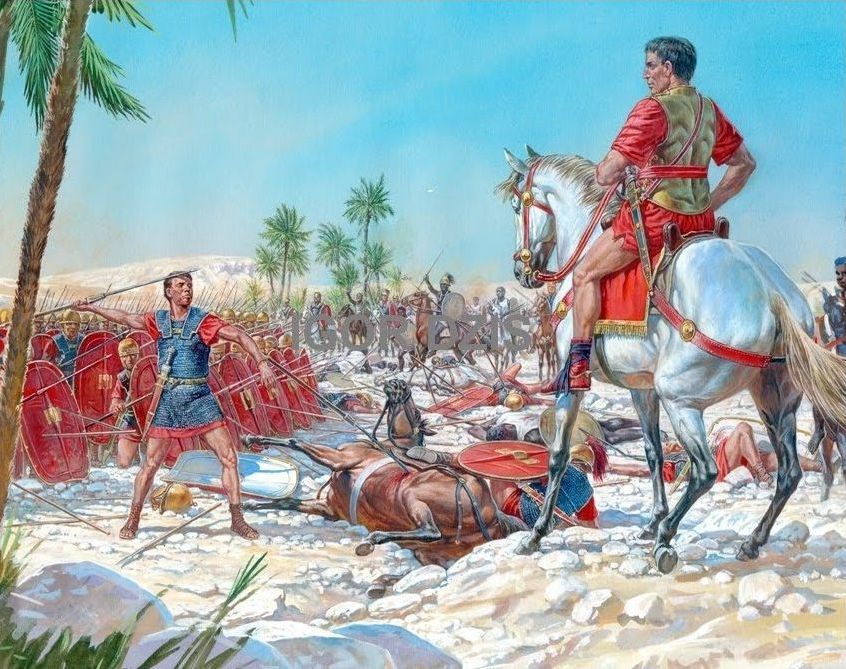

On one occasion during the African campaign against Metellus Scipio, Caesar was marking time at Ruspina while awaiting his veterans. His opponent, becoming emboldened, “advanced with his whole army and towered elephants” right up to Caesar’s ramparts. Caesar, without leaving his tent, received reports of the moves of the enemy and gave directions how to meet them. “This is the first instance in ancient military books where a commanding general is described as managing a battle just as he would today.”

In an emergency, even Caesar did not hesitate to snatch a shield, and to direct a battle from the first ranks by precept and example. Unlike Alexander, however, Caesar was never a beau sabreur; he was the intellectual captain. In this connection one should remember that when Caesar began his real military career he was several years older than Alexander was at the end of his eventful life.

In the work of Onesander, who in 49 A.D. dedicated to a Roman consul a work on the duty of a general, we see a full realization of the proper functions of the commander. He says that the science of the general avails more than his strength, and that a general who fights as a common soldier is like a pilot who leaves his post to perform the duties of a common seaman. Plutarch expressed special admiration for Hannibal because, although he had been in so many battles that one wearied of counting them, he had never been wounded.

By the time of the famous siege of Jerusalem, it was generally recognized throughout the army that a general should not endanger his command by taking unnecessary personal risks, for the soldiers under Titus protested against his exposing himself. It is given as one of the maxims of war by Vegetius that a leader should not personally fight except in an emergency, or as a last resort.

Tactics and strategy had become increasingly complex so that the safety of the army depended on the safety of the general. The evolution of generalship was, then, a steady, natural, and inevitable growth. The realization that it was entirely beyond the province of a general to make a practice of fighting with weapons was a contribution chiefly of the Romans.

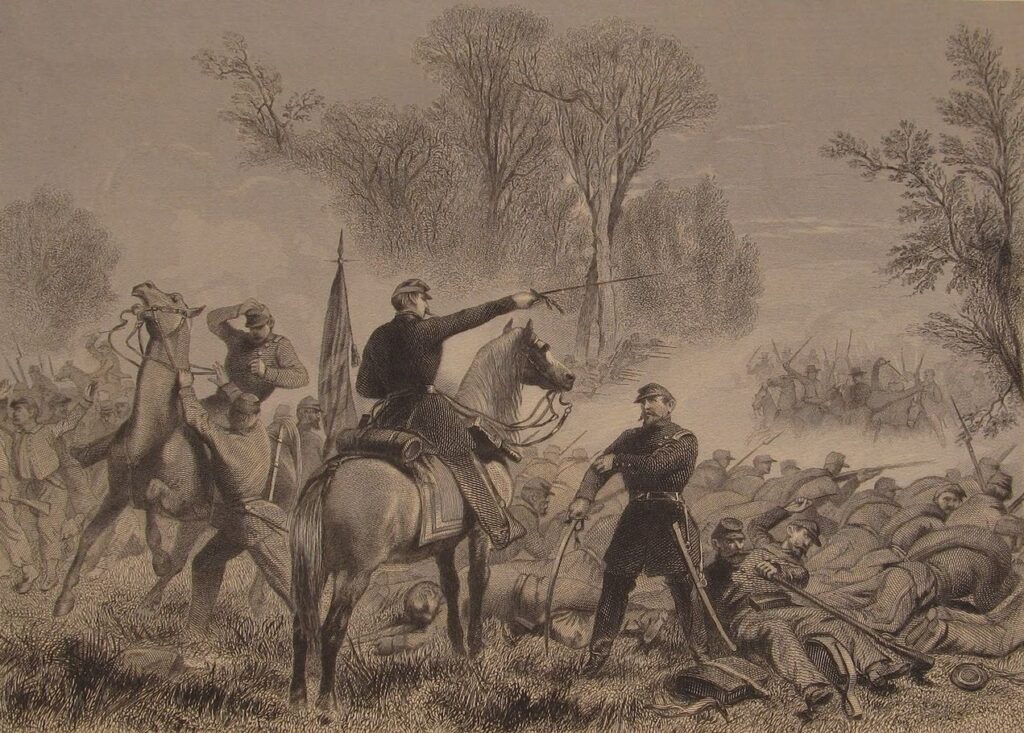

The lesson that antiquity teaches so clearly about the proper place for the commander has not always been heeded. Steele severely criticizes the Union general at the first battle of Bull Run because, instead of setting up his headquarters somewhere in the rear and directing his army as a whole, he was “at the very front, in the thick of the battle, scarcely exercising any influence on the action beyond the sound of his voice.”[2]

A lesson in sound generalship is available to all readers of Plutarch’s Life of Pelopidas: “Therefore Timotheus was right, when Chares was once showing the Athenians some wounds he had received, and his shield was pierced by a spear, in saying: ‘But I, how greatly ashamed I was, at the siege of Samos, because a bolt fell near me; I thought I was behaving more like an impetuous youth than like a general in command of so large a force.'”

______________________________

[1] Hogarth, in The Journal of Philology, XVII, p. 22 (1888)

[2] Matthew Forney Steel, American Campaigns, Volume I, p. 146. (1909)

In our day, it’s hard to think of any generals who had the guts to *lead* the troops. Stonewall Jackson comes to mind, but that was a long time ago. Feldmarschall Erwin Rommel was such an inspiration to his troops that when he was lying in a field hospital, forbidden by his doctors to move, his troops took up a collection and bought decent food from a nearby town to nurse him back to health.

Who among our “Perfumed Princes of the Pentagon” would inspire troops like that today?