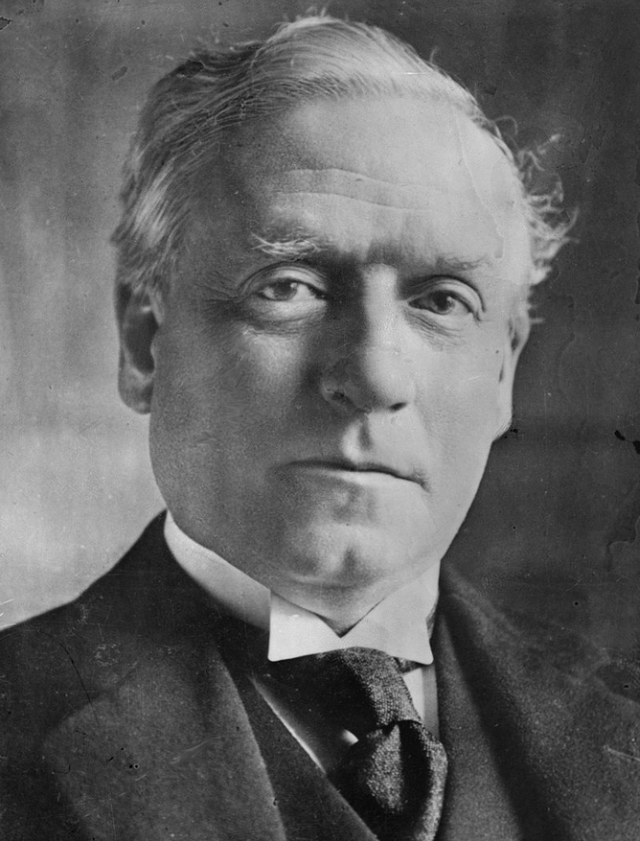

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Studies and Sketches, by H. H. Asquith (published 1924).

The middle of the 15th century saw the reinstatement of the Papacy in full authority at Rome. For one hundred and fifty years it had been discredited and weakened by exile, schism and disputed successions; by the unfilial attitude of the great potentates; by the growing hostility of the local churches to the centralized despotism and covetousness of the Curia; and by the attempts made at Constance and Basle to subject the Pope himself to the overriding authority of General Councils. The bark of St. Peter weathered all these storms, and had at last found what seemed a secure anchorage in its traditional haven. The Bull “Execrabilis” of Pius II (1460) asserts the claims of the Papal Monarchy in their fullest and most unlimited sense, and denounces as an abominable heresy, unheard of in former times, any appeal to any future Council.

It was appropriate that the new era should be opened by the first of the Humanist Popes, Nicholas V (1447-1455). A scholar, a great builder, an indefatigable collector, he surrounded himself with the most famous artists and men of learning of his day, and undertook, in a spirit of real magnificence, the task of making Rome the centre not only of Christendom but of Culture. He had friendly rivals in two of the most accomplished rulers of his own or any time; Cosimo de’ Medici, and Alfonso I of Naples. But he never relaxed his confident purpose that, as in religion, so in the external splendour of its buildings, and in its primacy in art and literature, Rome should be predominant over the whole Christian world. When Nicholas celebrated the Jubilee of 1450, and, two years later, the marriage and coronation of the Emperor Frederick III,[1] the re-established Papacy, like the rising buildings of St. Peter’s and the Vatican, with the frescoes of Fra Angelico and Benozzo Gozzoli, seemed to be reviving the glories of the Eternal City.

On the 29th May, 1453, Constantinople fell, and the Turk made good his foothold in Eastern Europe. It was an event that could easily have been foreseen, and if there had been anything like genuine unity in the Christian world, could as easily have been prevented. Incidentally it flooded Italy with a crowd of more or less erudite Greek refugees, who found a useful patron in their compatriot Cardinal Bessarion. It is a mistake to suppose that the influx of these Byzantine exiles first introduced into Italy a knowledge of the Greek classics in the original tongue. Neither Dante nor Petrarch knew any Greek to speak of, and Boccaccio very little; but for more than half a century there had been a steady importation of Greek MSS. from Constantinople, and at Florence, under Chrysoloras and his successors, the Greek language and literature had been systematically studied. “Most of the Greek Classics were brought to Italy by 1430, some twenty-three years before the Conquest of Constantinople by the Turks.”[2]

But the occupation by Mohammedans of the Capital of Eastern Christendom awoke the dreamers and dilettanti in Rome, with the Pope at their head, to the realities of the time in which they lived. Nicholas himself turned in his last years from his buildings and his manuscripts to preach to a cold and divided Europe a New Crusade.

Calixtus III (1455-1458) (the first Borgia; perhaps the most respectable member of a family which, in time, gave two Popes and eight Cardinals to the Church) was, at the date of his election, already a senile invalid; and his short and inglorious tenure of the Papacy was largely preoccupied in providing for his relatives. But he did what was in his power to arouse Europe against the common enemy of Christendom. By the dispersal of many of the newly-acquired treasures of the Vatican Library, he raised and equipped a fleet. And when the victorious march of the Mohammedans was at last arrested at Belgrade, in April, 1456, it is right to remember that, while the main share of the glory belongs to John Hunyadi, the great Hungarian was well helped in his almost desperate task by two Churchmen, Carvajal, the Papal Legate, and the heroic Friar Capistrano. Within a few months disease carried off both Hunyadi and Capistrano: an inestimable loss to the Christian cause.

When Calixtus III died in 1458, he was succeeded by a man of a totally different type — one of the characteristic figures of the Renaissance — a versatile rhetorician and diplomatist, who, after a youth and early manhood spent in the service of many masters, and enlivened by every kind of loose adventure, took Orders, reluctantly and late in life, as the best road to preferment, and had recently become a Cardinal. In the Conclave which followed the death of Calixtus, after much squalid intriguing between the French and Italian factions, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini was in the end elected, and assumed the title by which he is known in history — Pius II (1458-1464). He already posed as an old man (he was in fact only fifty-three), and was a victim, indeed almost a martyr, to the two chronic ailments, physical and moral, of the Popes of that era — gout and nepotism. But with all his shiftiness and worldliness, Pius II was as strenuous as either of his predecessors in the prosecution of the New Crusade. He brought to the cause not only remarkable powers of speech (in which he had no contemporary rival), but inexhaustible energy of purpose and spirit. Friars carried the summons to the faithful in every part of Europe, and the Pope anathematized all, whether kings or subjects, who should try to hinder the Crusade.

But the results were insignificant. The days of crusading were over. No one had foreseen or stated the insuperable difficulties of such an enterprise more clearly than Aeneas himself. So far back as 1454, a year only after the fall of Constantinople, while Nicholas V was still Pope, he had written: “How will you persuade this multitude of rulers to take up arms? Suppose they do, who is to be leader? How is discipline to be maintained? How is the Army to be fed? Who can understand the different tongues? Who will reconcile the English with the French, Genoa with Naples, the Germans with the Bohemians and Hungarians?[3] If you lead a small army against the Turks you will be defeated: if you lead a large one there will be confusion.”[4]

All this was as true and as apposite in 1464 as it was ten years before; indeed (as a glance at the political conditions, internal and external, of England, France, Germany, Bohemia, and Italy itself, is sufficient to show), anything like a general and effective concentration of the Christian States against the Turk was, from first to last, the idlest of dreams.

Pius II, decrepit and moribund, nevertheless resolved himself to take a personal part in the Holy War. In June, 1464, he took the Cross in St. Peter’s, and was carried thence to Ancona, where the rabble of so-called Crusaders were waiting in vain for the Venetian transports. When the ships at last appeared (after the bulk of the army had dispersed) the Pope was already dying (August, 1464). It is characteristic of the whole business that the Doge, who came with his Fleet, expressed the opinion that his arrival was a disappointment to the Pope, who had hoped to get rid of the expedition by throwing the blame on Venice.

Under the next Pontificate, that of Paul II (1464-1471), little was heard of the Crusade, and nothing was done to set it on foot. Paul, who tried to take up the Humanist tradition of Nicholas V, was primarily a busy connoisseur; his hand was heavy upon the tiresome literary pedants of his time;[5] but he was an impotent ruler of the Church.

At this point it may not be irrelevant to digress for a moment from the course of the narrative. The 15th century in Italy (as elsewhere in Europe) was singularly barren in the domain of creative Literature. After the death of Petrarch (1374) she produced not a single great original writer, until we come to Ariosto, Machiavelli and Guicciardini, whose work belongs mainly to the first quarter of the 16th century. But it is a commonplace of the historians, and one of the paradoxes of history, that in that same era and country we find an unexampled efflorescence of the finest and most spiritualized Art, side by side with perhaps the lowest moral standard ever reached in Christian times, both of personal and of public life.

The successor of Paul II was Sixtus IV (1471-1484), the first Rovere; a family which, if it could not quite rival the Borgias in sheer wickedness, almost outstripped them in successful cupidity and rapacity: it contributed, in its various branches, to the Church two Popes, and no less than twelve Cardinals. Sixtus himself is a curious illustration — such as only the Italian Renaissance could supply — of the sinister volcanic fires which might lie hidden for years in the breast of a learned and devout Franciscan friar. He coquetted in a half-hearted way with the Crusade; but his energies and ambitions were mainly absorbed in enriching his worthless kindred, and in attempting, by every kind of violence and chicanery, to secure for the Papal State the political hegemony of Italy.

Perhaps his masterpiece was the Pazzi Conspiracy, engineered in Rome, if not at the initiative, certainly with the connivance, of the Pope, whose political schemes were blocked by the power of the Medici at Florence. The two brothers, Lorenzo and Giuliano, were to be got rid of at all costs. In the end (the story is one of the most famous, or infamous, in the history of the Renaissance) they were inveigled into attending High Mass in the Duomo at Florence on Sunday the 26th April, 1478. At the moment when the Host was being elevated by the celebrant, Cardinal Raffaele Riario, a boy of not more than seventeen, a bastard son of a bastard son of the Pope, the assassins (of whom two were priests) fell upon the Medici brothers with their daggers. Giuliano was stabbed to death; Lorenzo was wounded, but escaped from the church alive. Florence took summary vengeance upon the conspirators; one of the ringleaders, Salviati, Archbishop of Pisa, was hanged forthwith, in his episcopal robes, from a window of the Palazzo Vecchio; and, in requital, the city was promptly laid under an Interdict by the Pope.

It is one of the many ironies in the character and career of Sixtus IV that he retained to the last his interest in theology, and his devotion to the Franciscan Order. In particular, he never wavered in his adhesion to the specially Franciscan doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin, to whom he dedicated two great churches in Rome, though, in the end, he agreed to allow belief in the doctrine to be an open question in the Church: in which situation it remained for the best part of four centuries.

Sixtus IV is principally known to the artists and tourists of the modern world as the creator of the Sistine Chapel, adorned under his supervision by the genius of Perugino and Botticelli, and, later, in the Pontificate of his nephew Julius II, by that of Michelangelo. It is perhaps not surprising that, to his contemporaries, he did not seem to have been called by Providence to rekindle the torch which, in the days of the great Crusades, had been lighted by prophets like St. Bernard, and carried by paladins like St. Louis.

The conqueror of Constantinople, Mohammed II, died in 1481,[6] and war at once broke out between his two incapable sons, Bajazet and Djem. Djem took refuge with the Knights of Rhodes; was bought from them, at the price of a Cardinal’s hat for the Grand Master, by the successor of Sixtus, Innocent VIII (1484-1492) (otherwise a rather scandalous nonentity); and was taken to Rome, where he lived in more or less gilded captivity, and played for years the part of a much-coveted pawn on the chess-board of Christian diplomacy.

This episode in history has a fitting anticlimax. On Ascension Day, 1492, Innocent VIII — who was nearing his own end — solemnly received at the Porta del Popolo, and bore in procession to the Vatican, a priceless present, which had been sent to him by the Sultan Bajazet: the Head of the Holy Lance, which pierced the Saviour on the Cross. While the dying Pope muttered his benediction to the populace, the Sacred Relic was held aloft by Cardinal Borgia, who was to buy his way a few weeks later to the Chair of St. Peter, and to make the name of Alexander VI the most infamous in the annals of the Papacy. Alexander’s relations with Bajazet soon became friendly and even intimate. In 1494 they struck a bargain, by which, in return for the assassination of his brother Djem, the Commander of the Faithful agreed to hand over to the Vicar of Christ the Seamless Coat, for which the soldiers cast lots on Calvary.

Twenty years later, in 1517, when the fading vision of a New Crusade still hovered fitfully over the marshes of European diplomacy, we find our own King Henry VIII remarking sagaciously to the Venetian Ambassador in London: “You are wise, and of your wisdom can understand that no general expedition against the Turk will ever be undertaken, so long as such treachery prevails among the Christian Powers that their sole thought is to destroy one another.”[7] And so it came to pass that the Crescent continued for centuries to fly over the Dome of St. Sophia.

______________________________

Footnotes

[1] Frederick III was the last Emperor to be crowned in Rome.

[2] Professor A. C. Clark : “The Library,” 4th series, Vol. II., No. V p. 877.

[3] He might have added to this troublesome list the Venetians, who insured themselves by making a commercial treaty with the Turks.

[4] Gibbon, Ch. lxviii.; Creighton, Vol. III., p. 150.

[5] The development at this time of the new art of printing struck a salutary blow at the perverted virtuosity of the early Humanists.

[6] In 1480 the famous portrait of Mohammed II, now in the National Gallery under the Layard bequest, was painted at Constantinople by Gentile Bellini, on a commission from the Government of Venice. In the same year, probably with the connivance of the Venetians, the Turks were able to land for the first time in South Italy, at Otranto.

[7] Creighton, Vol. V., p. 276.