Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 7 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 6: Commotion in the Hills)

The Division drove across Leyte with the roar of hundreds of motors. Yamashita was given no chance to regain his balance. In the welter of churning wheels and by-passed Japanese detachments, even generals came under fire.

One sultry day at the front a sniper seemed to open fire every time the Assistant Division Commander removed his helmet to mop his brow. The sniping became so pointed that a lieutenant decided that the shots were aimed at his superior’s shining bald spot. “By God, Sir,” he said, “your pate is the target.” Henceforth the chunky brigadier kept his helmet on. The sniper then sought other targets.[1]

On another occasion the Division Commander[2] and a colonel stood bent over a map when a Japanese broke out of a clump of underbrush twenty yards off. He charged the two officers with a grenade, a dagger, and Banzai yells. The colonel whipped out his pistol and fired—and missed. He fired again, missed again. The Jap came on. The Division Commander braced himself to meet the Jap with a pair of dividers. The colonel kept on firing. His weapon, a .45 caliber pistol, is next to the bayonet the least efficient tool in the Army’s arsenal. He fired seven times. The shots missed — or jammed— seven times. He killed his assailant with the eighth, and last, bullet.

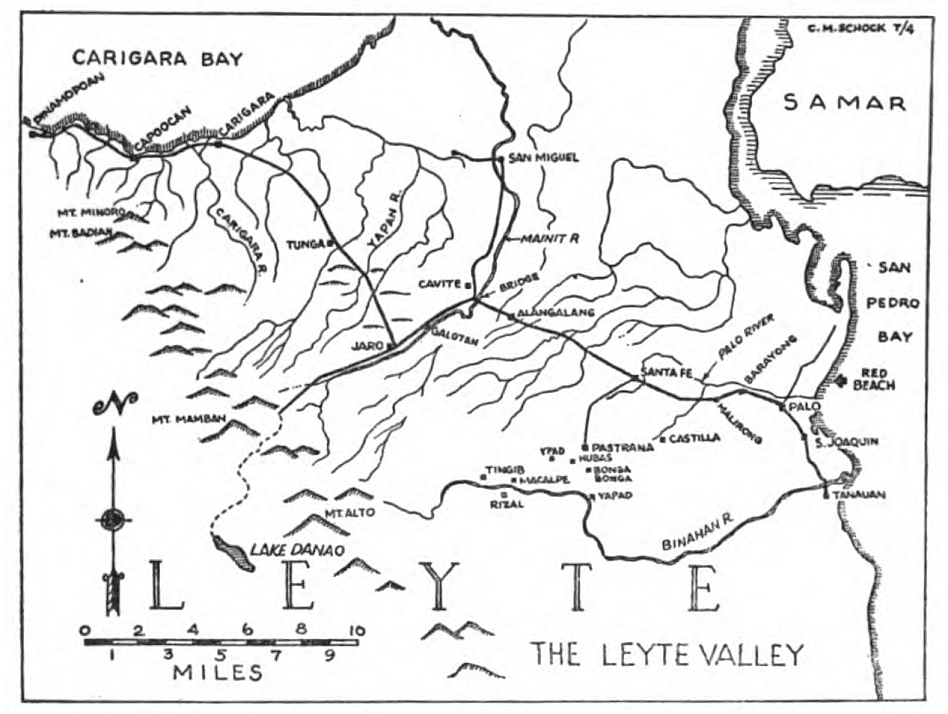

The Leyte Valley is roughly thirty-five miles long and ten miles wide. Scores of villages dot its expanse of plantations, rice paddies and marshy fields. Forest-covered mountain ranges rise on its western flank. The valley is crossed by many meandering streams. During the dry season the country between Palo and Carigara is a tropical paradise; the skies are blue, and rice, bananas, coconuts, breadfruit and papaya grow everywhere. But in the rainy months the fields are flooded and the streams become swollen rivers, and swamps surround the stilts of native huts. Then the road to Carigara on the island’s opposite coast is transformed into a ribbon of slime. The network of village paths soak into a spiderweb of knee-deep mud. The battle for the Leyte Valley was a cataract of motion along these roads and trails.

One battalion struck 8,000 yards across the Leyte Valley and stormed the town of Castilla, southwest of Palo. The last Japanese soldier alive in that community bayoneted an American in search of a drink of water. Another force struck south from San Joaquin and reached the banks of the Kabuyan River. Patrols sent into the village of Tanauan made contact with a friendly division[3] which had invaded Leyte farther to the south. So, an unbroken forty mile front on Leyte’s east coast was established.

Mindful of enemy deviltry, the infantry teams barred all civilians from entering the captured towns. The Division’s Counter Intelligence Corps placed pro-Japanese town officials under arrest. From the beginning of the liberation, little love was lost between the soldiers and the populace. The average dogface had little respect for the stubborn courage of the average guerilla; he left the glorification of the poor “Flips” to the propagandists at home. Many an unwilling and homesick liberator despaired of figuring out why men should die to liberate wretched villages and squalor set in acres of stinking mud. His own unhappiness developed in him a tendency — hardening as the messy months rolled on — to brush the barrio folks aside or to ignore them all except the young village women who had the hips of children and sad black eyes and long black hair with an unwashed smell.

But morale ran high when the first mail from home was distributed in the foxholes; everywhere men sat hunched over letters, some grim, some smiling, some with trembling hands, reading on at night by flashlight under ponchos, still reading after the rain had blurred the ink. Meanwhile the kitchen crews moved up their pots and pans and portable stoves, and through the sound of falling rain, the incessant rumble of trucks and the rataplan of machine guns drifted the aroma of hot biscuits.

While the rifle platoons gathered their breath for the next spring, the men of the Division’s Signal Company worked around the clock. Within a week after the landing they had lost a score of men and laid a thousand miles of wires. They had installed scores of telephones, radio and radar units, toiling on with carbines slung and sweat pouring from under their helmets. One group went through five fire fights before it could lay its wire. Another group of nine was wiped out by an artillery hit. A joker planted a sign on the spot which said, “Hard & Haggard, Electrical Installations.”

In many perilous spots artillery observers and signal men worked hand in hand. They were the eyes and ears of the cannoneers. Without forward observation and quick intelligence about targets far in front, the batteries would be blind.

An artillery reconnaissance party proceeding through brush parallel to the valley highway came face to face with a Japanese combat patrol prowling through the brush in the opposite direction. Only fifteen feet of sword grass separated the cannoneers and the Japs when they sighted one another. Muzzle to muzzle, a fusillade ensued. Sergeant John Huey of Franklin, Pennsylvania, plunged forward and killed two of the enemy. Bob Tougas of Detroit killed one Jap and stopped a Jap grenade. Corporal Bruce Gramley of DuBois Town, Pennsylvania, killed another. Sergeant Joseph Dawson of Kinden, Virginia, killed one more. And Corporal John Hutchinson of Boston, Massachusetts, was pushed over the edge of a swamp in the scramble. He tangled with three grenade-heaving enemies. A minute later he emerged. “Did they get away?” his comrades asked. Hutchinson shook his head. “They are dead,” he said. This happened near Malirong on October 27.

Spearhead of the drive through the Leyte Valley was the Division’s Thirty-Fourth Infantry Regiment. Nothing that General Yamashita threw in its way could stop it. In six days it cut Leyte in two.

Its progress was swift and sure. The battalions “leapfrogged” one another. Artillery fire paved the way. There was resistance at the Manabana River bridge, but mortars were brought into position in a matter of minutes. Mortar fire and an infantry charge drove the defenders away from the road and into the flanking hills. By late afternoon of October 26 the Second Battalion seized Santa Fe and dug in for the night. On the following day the First Battalion passed through the Second and pushed on another seven thousand yards to the outskirts of the town of Alangalang. Two thousand yards in front, broad and muddy, flowed the main water barrier of the Leyte Valley— the Mainit River.

The Japanese contested every mile of highway with tenacious rear guard actions. Each mile was paid for with agony and sweat, and each night rains fell.

Between Palo and Alangalang five bridges had been blasted by the retreating foe. Others were set afire in the face of the Division’s scouts. An arch had been blown out of the center of a concrete bridge; two steel bridges were completely destroyed. But with the assault teams moved the Combat Engineers. Their bulldozers, power saws, timbers and steel trestles accompanied the advance; new bridges, or by-passes, were thrown across the streams in a matter of hours while infantry kept harassing snipers at bay. Leading elements forded the streams, their rifles held high. Or they ferried across on palm logs and rafts improvised from tarpaulins stuffed with jungle grass and brush. And always there was a fire fight.

In one of the fights for a river crossing, Bill Rigdon of Davenport, Florida, saw a friend collapse under bullets ripping from a bamboo grove. He saw his friend thresh about at the edge of the road. He saw the strike of bullets as the snipers strove to finish their job. Bill went to the rescue. He carried his friend two hundred yards through rifle fire and to the rear.

Private Walter Petrowski, an artilleryman from Lowell, Massachusetts, too, saw a comrade sag, hit by enemy bullets. The wounded man was bleeding to death. He cried for help but no medic was near. Petrowski ran forward. He tied a tourniquet around the bleeding man’s thigh. Before he had finished, a burst of machine gun fire killed him at the side of the one he had tried to save.

Cannoneer R. D. Clark of Canton, North Carolina, then braved the same machine gun. He crawled forward with a field telephone and registered his battery on the enemy strongpoint. Shellfire destroyed the Jap gunners.

Driving his battalion commander in a radio jeep on a reconnaissance mission was Private Harry Meade. The jeep ran into a machine gun ambush and the party was pinned down in a road side ditch. “Somebody’s got to go back and warn the leading echelon,” the battalion commander said. Meade volunteered. He jumped back into the riddled jeep. At breakneck speed he drove through sprays of automatic fire. The jeep’s antenna was shot away. But Meade came through in time to warn the advancing force.

Staff Sergeant Frank Marchant of Muskogee, Oklahoma, dragged three wounded men out of the path of certain death, then guarded them until help arrived. Three scouts of the advance guard suddenly encountered a company of counter-attacking Japanese; they held their ground until their platoon could arrive and deploy. Corporal Carl F. Wolf of Whitlow, California, was wounded and the medics were at his side. “Evacuate me?” said Wolf. “Not yet.” He remained with his squad until the attack was repulsed. In a drenching night rain Corporal Calvin Haren of Denton, Texas, saw a Japanese demolition team of three move stealthily toward a group of anti-tank guns well within the perimeter. The Texan blocked their way and shot two; then a machine gun opened up, killing the third.

In the sweep up Leyte Valley, tanks struck mines. There were rumbling explosions as mines burst in clouds of fire, rock and mud. There was hidden TNT in the roadbeds and under innocent appearing thresholds; and high explosives attached to telephones, stray fountain pens and ladies’ slippers. There were pottery mines and wooden mines which defied mechanical detectors; the probing bayonet was then the only resort. Even coconuts were turned into traps; filled with explosive and a grenade that would burst under slight pressure upon the husk. Men of the mine disposal squads disarmed and removed more than two hundred improvised bombs along the Santa Fe Trail.

Two hours before dawn of October 28 the battalions were alerted for the attack on the Mainit River Line. Men rolled their combat packs and ate their breakfast in the dark. Early morning mists rose from the marshes. The march began.

The First Battalion took the lead. Scouts moved far in front. Strong patrols secured the flanks. The advance party followed the point, and they in turn were followed by the advance guard support, one company strong. Then came the main assault force, stretched out in open column to both sides of the highway: the riflemen, the mortar men and the machine gun crews. Cub planes ranged ahead for observation.

The task force approached the village of Alangalang in almost complete silence. There were no Japanese. The population had fled into the hills. Only the howling of dogs greeted the scouts.

Patrols branched off to right and left to comb the houses. Company after company traversed the ghost town and pushed on to ward the river. Combat engineers made short shift of obstacles along the way. Small pieces of paper propped onto twigs were used to mark the presence of mines. Here and there Japanese corpses lay, artillery victims often without legs or arms. Already they had swollen under the dampness and the heat. Flies buzzed about the cadavers. Some of the dead had been chewed up by dogs. The scouts were more alert and the silence was more profound. Through foliage ahead loomed the large steel bridge which spanned the Mainit River between steep banks.

The collision was abrupt and violent. The crack of rifles, the urgent chatter of automatic guns and the dry thumping of mortars mingled in a tempest of noises. There were the yells of rage, the mute agony of hesitation, the cries of the wounded, the sounds made by many running men, and there were the angry answering barks of the Garands.

At first not much could be seen of the Japanese positions on the river’s far side. Only lingering wisps of blue smoke. Pillboxes were covered with earth, and grass grew from this earth. The enemy gunners fired through narrow ports built into the revetments. Tunnels opening upon clumps of underbrush served as the strongpoints’ exits. But after a while the continuous passage of bullets set fire to the grass in front of the pillboxes. That betrayed their location.

The leading battalion deployed: one company to the right of the road, one company to the left. Through rice fields the skirmish lines pushed toward the river. They reached the river bank on both sides of the bridge. At this point more machine guns hidden on the opposite bank erupted in a satanic concert. The whole battalion was pinned down on the river’s edge. A crossing was impossible. To move on meant to die.

A withdrawal was ordered. But the men would not move. They clung to the mud. Hostile machine guns raked the fields behind them. To move rearward, too, meant certain death.

Tanks lumbered forward. They stopped at the river’s bank and sprayed the Japanese defenses with machine guns. Shells from their 75 millimeter cannon transformed pillboxes into wreckage. Still, the companies were unable to move. A heavy volume of sniper fire from treetops to their rear added to their plight.

Now a Cannon Company platoon entered the turmoil. The cannoneers sent shells screaming across the river as fast as they could load their pieces. The platoon’s ammunition was soon exhausted. Another platoon of Cannon Company men moved for ward and continued the shelling. Under this punishment the Japanese ducked low. In rapid, intermittent dashes the companies on the river bank moved to safer positions. Another way had to be found to force the river. Scouting parties roamed the adjoining woods. At intervals they entered the river, searching for a ford.

Meanwhile, an enemy raiding party attacked a battery of field artillery almost a mile to the rear of the front. By chance, Corporal Albert Nichols of Pauls Valley, Oklahoma, was poking around for souvenirs. He saw a crouched figure running through under growth. At first glance he thought it was a native. But why should a native run at a crouch? Nichols looked again. This time he saw twenty Japanese about to rush his battery.

Nichols grabbed his rifle, threw himself on the ground, fired. The Japanese also fired, and they hurled grenades. The corporal heard bullets and grenade fragments strike his gun mount. He heard bullets crash into ammunition chests a little way off. He also felt a pain in his left hand. The hand was smashed. But Nichols stayed at his post. He fired. Singlehanded, he dispersed the raiders.

Not long after noon patrols reported that they had found a ford across the Mainit River. It lay some five hundred yards to the north of the embattled bridge. There was a bend, and the banks were covered with jungle. At this point the river’s edge was an almost vertical twenty-foot drop.

“A ford?” Colonel Newman said quietly, “That’s fine.”

The regiment struck at 1400. By 1500 it had forced the Mainit River and captured the bridge. The intervening hour included that rarest of events in modern war: a bayonet charge over hundreds of yards of open ground.

“Red” Newman launched a coordinated two-battalion attack. Once more the First Battalion advanced to the river’s edge. Again it was pinned down in a holocaust of fire. It kept the enemy’s attention riveted to the bridge and its immediate vicinity. Meanwhile, the Second Battalion ducked low and hastened upstream to the ford.

Eight hundred infantrymen forded the Mainit River without meeting opposition. Squad after squad dropped down the steep embankment, weapons and ammunition held aloft. Many waded up to their necks in swirling water. Some lost their footing, but no weapon was lost. Ropes tied to trees on the opposite bank helped the men to hoist themselves onto the Jap side of the river. There was a wall of jungle, a belt of palm plantation, and then a stretch of open ground. The bridge and the enemy’s highway defenses lay five hundred yards to the south.

“Fix bayonets!”

There was a subdued clatter as the short, black blades were slipped into the bayonet studs of the Garands.

“As skirmishers — forward!”

The skirmish lines emerged from the jungle and crossed the belt of palms at a run. “Fox” Company was in the lead and its commander, Captain Paul Austin of Burleson, Texas, well out in front. From fifty yards up the river bank, Japanese flank detachments opened fire. Machine guns hammered from a coconut grove on the left. Enemy mortars belched high explosive in a vain attempt to stem the tide. The bayonet charge swept forward. Men fired from the hip as they advanced. Others cleared the way with grenades. Automatic riflemen fired their twenty-pound weapons from the shoulder. Machine gunners kept pace and each hundred yards they halted briefly to spray the enemy lines.

A flanking attack is the most deadly form of attack. The pace was so swift that Japanese mortar shells burst in the rear of the advancing formations. The infantrymen yelled: Indian yells, their regiment’s battle-cry, “Lorraine! Lorraine!”, blood-curdling howls of every description, curses, hymns, obscenities, hysteric laughter. Here and there Japanese spider-holes, dug like wagon wheels to enable firing in all directions, were overrun. Grenades, rifle butts, cold steel did their work. In the dampness hung the smell of blood.

Captain Austin led the assault; between words of encouragement and quick directions he was shouting like a berserker. Three enemies armed with mortars died at his hands. His men overran mortar positions without a halt. His own mortars supported the charge by sending shells into more distant Japanese emplacements. Homer McClure of Chattanooga, Tennessee, saw a Jap machine gun cut down several men in his platoon. He loped toward the machine gun. Thirty yards from it he stumbled and fell. He raised himself to his knees and fired into the enemy nest. Machine gun bullets hit him while he fired. Not until the last round of his clip of eight had left his rifle did he fall, mortally wounded.

Sergeant James F. Schmidt of North Muskegon, Michigan, saw a soldier of his squad collapse in a spurt of machine gun fire. He rushed forward, and crawling low, he dragged the wounded man into the shelter of a tree. All this time machine gun bullets from his own company’s guns as well as slugs from Jap guns whipped low above his head.

In the midst of the bayonet charge four medical aid men carrying litters ran a zig-zag race with death. They were carrying wounded out of the killing zone. Private Serafino Guinta of Brooklyn took charge of a machine gun after both the squad leader and the gunner had crumpled under hostile fire; he kept the gun spitting lead until Jap mortarmen had zeroed in on his niche. Then Guinta grabbed the gun and carried it to an alternate position. The weapon was so hot from continuous firing that the volunteer gunner badly scorched both hands. After that Guinta dashed to a nearby tank to secure an additional supply of ammunition. He carried the ammunition back to his gun. Despite his seared hands he fired until a squad of Japs threatened to close in. After his last shot was fired he again grabbed his gun and threw it onto the tank to save it from enemy hands. He babbled in a fever as aid men carried him away.

A sniper’s bullet knocked away the helmet of Clinton Short of Parkersburg, West Virginia. He was leading a squad in the assault. Bareheaded he ran on, calling on his men to follow, pointing out targets right and left. Twenty yards to one side a Japanese behind a mortar threw a grenade at Short. The burst fell wide. Deafened by the concussion, Short pounced on the Jap. Both roared with rage as they collided. The yellow man brandished another grenade. The West Virginian saw the opening, ran him through with the bayonet, then fired for good measure. A minute later Short walked boldly against the next emplacement. “Follow me!” he cried. Toward the end of the long assault he fell.

Commanding the lead squad of his platoon was Sergeant Ernest (“Reckless”) Reckman of Valley Stream, New York. His whooping men rushed past a camouflaged spider-hole full of Japs. Reckman’s quick eyes spotted the masked position. He rallied his squad and led it in a concentric charge against the hole. At another point he discovered a cunningly hidden mortar emplacement. An instant later he rushed it, tossing a grenade as he ran. The grenade roared and Reckman jumped into the emplacement. None of the stunned enemy came out alive. The charge now reached the Japanese machine gun positions. A fighting man named William Thomas, from Ft. Wayne, Indiana, almost fell over his squad leader who had fallen with a burst of machine gun slugs in his body. William Thomas stopped, dragged his mortally wounded noncom to a hollow in the ground, then rushed forward again and silenced the enemy machine gunner in a close-quarter duel. Almost simultaneously a fighting man from Kentucky, also named Thomas,[4] crossed the swift-flowing Mainit River under a hail of bullets. He climbed the high bank and knocked out a machine gun nest whose crew had attempted to kill him while he was wading chest-deep in water. With fine marksmanship this second Thomas then pinned down the crews of three other hos tile dugouts until reinforcements arrived to complete the job.

It was a Kentuckyman, too, Sergeant Roy Floyd of Eubank, who first reached the bridge. A third son of Kentucky[5] broke through to the bridgehead almost shoulder to shoulder with Floyd; a shell wailed and there was the crash and the quick stab of flame, and fragments. The soldier fell. His back was torn open. Nonetheless, this wounded Kentuckian stood up again and dragged himself to the nearest American mortar. He told the mortarmen exactly where to fire to destroy the gun that had hurt him. Then he collapsed.

The Mainit River bridge was captured. Jap survivors scuttled through undergrowth like hares. The short, ugly noises of taking life moved on into the woods to the west.

The Japanese had left the bridge intact, but not by choice. They had mined the bridge with 200-pound bombs and with several cases of artillery ammunition. Wires attached to set off the demolition charges led to a banana grove on the west bank of the river. But the enemies stationed at the far end of the wires had met death. There had been three: one had his head bashed in; another’s neck had been broken by a rifle butt; and the third had blown out his guts with a grenade.

A team of engineers under Sergeant McPeters of Bragg City, Missouri, knocked holes into the deck of the bridge. McPeters then disarmed the demolition arrangement.

Soon tanks, trucks, bulldozers and halftracks rumbled steadily across the Mainit River.

(Continue to Chapter 8: Death-Dance in Pastrana)

_________________________________________

[1] Brigadier General Kenneth F. Cramer of Wethersfield, Connecticut, one time State Senator, State Commander of the American Legion, helped to guide the 24th Division’s campaigns in New Guinea, Biak and the Philippines. He was frequently cited for outstanding gallantry.

[2] Major General F. A. Irving commanded the 24th Division until November 18, 1944. The colonel was William J. Verbeck, commander of the 21st Infantry Regiment, now teaching military science at West Point.

[3] The 96th Infantry Division.

[4] Private First Class Edward R. Thomas of Trappist, Kentucky.

[5] Private First Class James E. Lacefield, Louisville, Kentucky.