Editor’s note: Here follows the thirteenth chapter of The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War, by Winston S. Churchill (published 1898). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XIII: NAWAGAI

"When the wild Bajaur mountain men lay choking with their blood,

And the Kafirs held their footing..."

"A Sermon in Lower Bengal," SIR A. LYALL.

Few spectacles in nature are so mournful and so sinister as the implacable cruelty with which a wounded animal is pursued by its fellows. Perhaps it is due to a cold and bracing climate, perhaps to a Christian civilisation, that the Western peoples of the world have to a great extent risen above this low original instinct. Among Europeans power provokes antagonism, and weakness excites pity. All is different in the East. Beyond Suez the bent of men’s minds is such, that safety lies only in success, and peace in prosperity. All desert the falling. All turn upon the fallen.

The reader may have been struck, in the account of the fighting in the Mamund Valley, with the vigour with which the tribesmen follow up a retreating enemy and press an isolated party. In war this is sound, practical policy. But the hillmen adopt it rather from a natural propensity, than from military knowledge. Their tactics are the outcome of their natures. All their actions, moral, political, strategic, are guided by the same principle. The powerful tribes, who had watched the passage of the troops in sullen fear, only waited for a sign of weakness to rise behind them. As long as the brigades dominated the country, and appeared confident and successful, their communications would be respected, and the risings localised; but a check, a reverse, a retreat would raise tremendous combinations on every side.

If the reader will bear this in mind, it will enable him to appreciate the position with which this chapter deals, and may explain many other matters which are beyond the scope of these pages. For it might be well also to remember, that the great drama of frontier war is played before a vast, silent but attentive audience, who fill a theatre, that reaches from Peshawar to Colombo, and from Kurrachee to Rangoon.

The strategic and political situation, with which Sir Bindon Blood was confronted at Nawagai on the 17th of September, was one of difficulty and danger. He had advanced into a hostile country. In his front the Mohmands had gathered at the Hadda Mullah’s call to oppose his further progress. The single brigade he had with him was not strong enough to force the Bedmanai Pass, which the enemy held. The 2nd Brigade, on which he had counted, was fully employed twelve miles away in the Mamund Valley. The 1st Brigade, nearly four marches distant on the Panjkora River, had not sufficient transport to move. Meanwhile General Elles’s division was toiling painfully through the difficult country north-east of Shabkadr, and could not arrive for several days. He was therefore isolated, and behind him was the “network of ravines,” through which a retirement would be a matter of the greatest danger and difficulty.

Besides this, his line of communications, stretching away through sixty miles of hostile country, or country that at any moment might become hostile, was seriously threatened by the unexpected outbreak in the Mamund Valley. He was between two fires. Nor was this all. The Khan of Nawagai, a chief of great power and influence, was only kept loyal by the presence of Sir Bindon Blood’s brigade. Had that brigade marched, as was advocated by the Government of India, back to join Brigadier-General Jeffreys in the Mamund Valley, this powerful chief would have thrown his whole weight against the British. The flame in the Mamund Valley, joining the flame in the Bedmanai Pass, would have produced a mighty conflagration, and have spread far and wide among the inflammable tribesmen. Bajaur would have risen to a man. Swat, in spite of its recent punishment, would have stirred ominously. Dir would have repudiated its ruler and joined the combination. The whole mountain region would have been ablaze. Every valley would have poured forth armed men. General Elles, arriving at Lakarai, would have found, instead of a supporting brigade, a hostile gathering, and might even have had to return to Shabkadr without accomplishing anything.

Sir Bindon Blood decided to remain at Nawagai; to cut the Hadda Mullah’s gathering from the tribesmen in the Mamund Valley; to hold out a hand to General Elles; to keep the pass open and the khan loyal. Nawagai was the key of the situation. But that key could not be held without much danger. It was a bold course to take, but it succeeded, as bold courses, soundly conceived, usually do. He therefore sent orders to Jeffreys to press operations against the Mamund tribesmen; assured the Khan of Nawagai of the confidence of the Government, and of their determination to “protect” him from all enemies; heliographed to General Elles that he would meet him at Nawagai; entrenched his camp and waited.

He did not wait long in peace. The tribesmen, whose tactical instincts have been evolved by centuries of ceaseless war, were not slow to realise that the presence of the 3rd Brigade at Nawagai was fatal to their hopes. They accordingly resolved to attack it. The Suffi and Hadda Mullahs exerted the whole of their influence upon their credulous followers. The former appealed to the hopes of future happiness. Every Ghazi who fell fighting should sit above the Caaba at the very footstool of the throne, and in that exalted situation and august presence should be solaced for his sufferings by the charms of a double allowance of celestial beauty. Mullah Hadda used even more concrete inducements. The muzzles of the guns should be stopped for those who charged home. No bullet should harm them. They should be invulnerable. They should not go to Paradise yet. They should continue to live honoured and respected upon earth. This promise appears to have carried more weight, as the Hadda Mullah’s followers had three times as many killed and wounded as the candidates for the pleasures of the world to come. It would almost seem, that in the undeveloped minds of these wild and superstitious sons of the mountains, there lie the embryonic germs of economics and practical philosophy, pledges of latent possibilities of progress.

Some for the pleasures of this world, and some

Sigh for the prophet's paradise to come.

Ah! take the cash and let the credit go,

Nor heed the rumble of a distant drum.

OMAR KHAYYAM

It is the practice of wise commanders in all warfare, to push their cavalry out every evening along the lines of possible attack, to make sure that no enemy has concentrated near the camp in the hopes of attacking at nightfall. On the 18th, Captain Delamain’s squadron of the 11th Bengal Lancers came in contact with scattered parties of the enemy coming from the direction of the Bedmanai Pass. Desultory skirmishing ensued, and the cavalry retired to camp. Some firing took place that night, and a soldier of the Queen’s Regiment who strayed about fifty yards from his picket, was pulled down and murdered by the savage enemies, who were lurking all around. The next evening the cavalry reconnoitered as usual. The squadron pushed forward protected by its line of advanced scouts across the plain towards the Bedmanai Pass. Suddenly from a nullah a long line of tribesmen rose and fired a volley. A horse was shot. The squadron wheeled about and cantered off, having succeeded in what is technically called “establishing contact.”

A great gathering of the enemy, some 3000 strong, now appeared in the plain. For about half an hour before sunset they danced, shouted and discharged their rifles. The mountain battery fired a few shells, but the distance was too great to do much good, or shall I say harm? Then it became dark. The whole brigade remained that night in the expectation of an attack, but only a very half-hearted attempt was made. This was easily repulsed, one man in the Queen’s Regiment being killed among the troops.

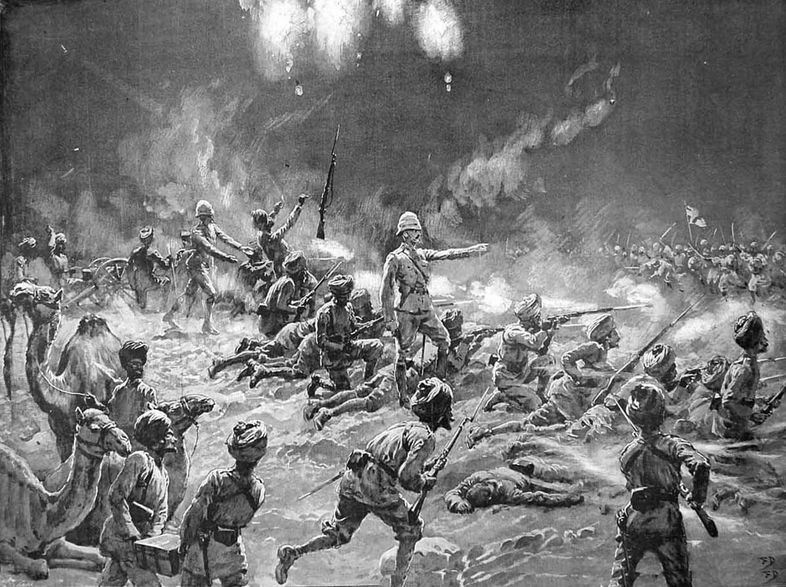

On the 20th, however, definite information was received from the Khan of Nawagai, that a determined assault would be made on the camp that night. The cavalry reconnaissance again came in touch with the enemy at nightfall. The officers had dinner an hour earlier, and had just finished, when, at about 8.30, firing began. The position of the camp was commanded, though at long ranges, by the surrounding heights. From these a searching rifle fire was now opened. All the tents were struck. The officers and men not employed in the trenches were directed to lie down. The majority of the bullets, clearing the parapets of the entrenchment on one side, whizzed across without doing any harm to the prostrate figures; but all walking about was perilous, and besides this the plunging fire from the heights was galling to every one.

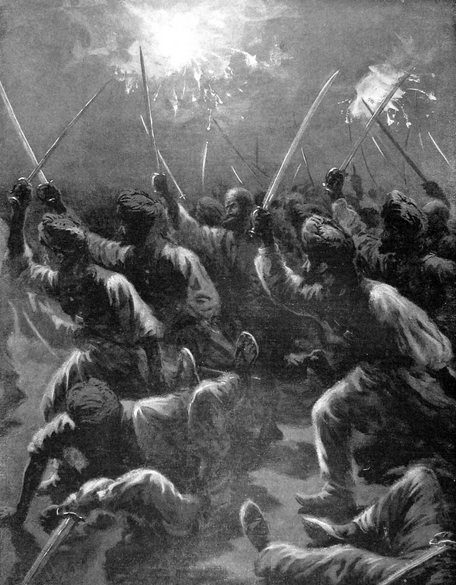

Determined and vigorous sword charges were now delivered on all sides of the camp. The enemy, who numbered about 4000, displayed the greatest valour. They rushed right up to the trenches and fell dead and dying, under the very bayonets of the troops. The brunt of the attack fell upon the British Infantry Regiment, the Queen’s. This was fortunate, as many who were in camp that night say, that such was the determination of the enemy in their charges, that had they not been confronted with magazine rifles, they might have got into the entrenchments.

The fire of the British was, however, crushing. Their discipline was admirable, and the terrible weapon with which they were armed, with its more terrible bullet, stopped every rush. The soldiers, confident in their power, were under perfect control. When the enemy charged, the order to employ magazine fire was passed along the ranks. The guns fired star shell. These great rockets, bursting into stars in the air, slowly fell to the ground shedding a pale and ghastly light on the swarming figures of the tribesmen as they ran swiftly forward. Then the popping of the musketry became one intense roar as the ten cartridges, which the magazine of the rifle holds, were discharged almost instantaneously. Nothing could live in front of such a fire. Valour, ferocity, fanaticism, availed nothing. All were swept away. The whistles sounded. The independent firing stopped, with machine-like precision, and the steady section volleys were resumed. This happened not once, but a dozen times during the six hours that the attack was maintained. The 20th Punjaub Infantry, and the cavalry also, sustained and repulsed the attacks delivered against their fronts with steadiness. At length the tribesmen sickened of the slaughter, and retired to their hills in gloom and disorder.

The experience of all in the camp that night was most unpleasant. Those who were in the trenches were the best off. The others, with nothing to do and nothing to look at, remained for six hours lying down wondering whether the next bullet would hit them or not. Some idea of the severity of the fire may be obtained from the fact that a single tent showed sixteen bullet holes.

Brigadier-General Wodehouse was wounded at about eleven o’clock. He had walked round the trenches and conferred with his commanding officers as to the progress of the attack and the expenditure of ammunition, and had just left Sir Bindon Blood’s side, after reporting, when a bullet struck him in the leg, inflicting a severe and painful, though fortunately not a dangerous, wound.

Considering the great number of bullets that had fallen in the camp, the British loss was surprisingly small. The full return is as follows:—

BRITISH OFFICERS.

Wounded severely—Brigadier-General Wodehouse.

" slightly—Veterinary-Captain Mann.

BRITISH SOLDIERS.

Killed. Wounded.

Queen's Regiment... 1 3

NATIVE RANKS—Wounded, 20.

FOLLOWERS— " 6.

Total, 32 of all ranks.

The casualties among the cavalry horses and transport animals were most severe. Over 120 were killed and wounded.

The enemy drew off, carrying their dead with them, for the most part, but numerous bodies lying outside the shelter trench attested the valour and vigour of their attack. One man was found the next morning, whose head had been half blown off, by a discharge of case shot from one of the mountain guns. He lay within a yard of the muzzle, the muzzle he had believed would be stopped, a victim to that blind credulity and fanaticism, now happily passing away from the earth, under the combined influences of Rationalism and machine guns.

It was of course very difficult to obtain any accurate estimate of the enemy’s losses. It was proved, however, that 200 corpses were buried on the following day in the neighbourhood, and large numbers of wounded men were reported to have been carried through the various villages. A rough estimate should place their loss at about 700.

The situation was now cleared. The back of the Hadda Mullah’s gathering was broken, and it dispersed rapidly. The Khan of Nawagai feverishly protested his unswerving loyalty to the Government. The Mamunds were disheartened. The next day General Elles’s leading brigade appeared in the valley. Sir Bindon Blood rode out with his cavalry. The two generals met at Lakarai. It was decided that General Elles should be reinforced by the 3rd Brigade of the Malakand Field Force, and should clear the Bedmanai Pass and complete the discomfiture of the Hadda Mullah. Sir Bindon Blood with the cavalry would join Jeffreys’ force in the Mamund Valley, and deal with the situation there. The original plan of taking two brigades from the Malakand to Peshawar was thus discarded; and such troops of Sir Bindon Blood’s force as were required for the Tirah expedition would, with the exception of the 3rd Brigade, reach their points of concentration via Nowshera. As will be seen, this plan was still further modified to meet the progress of events.

I had rejoined the 3rd Brigade on the morning of the 21st, and in the evening availed myself of an escort, which was proceeding across the valley, to ride over and see General Elles’s brigade. The mobilisation of the Mohmand Field Force was marked by the employment, for the first time, of the Imperial Service Troops. The Maharaja of Patiala, and Sir Pertab Singh, were both with the force. The latter was sitting outside his tent, ill with fever, but cheery and brave as ever. The spectacle of this splendid Indian prince, whose magnificent uniform in the Jubilee procession had attracted the attention of all beholders, now clothed in business-like khaki, and on service at the head of his regiment, aroused the most pleasing reflections. With all its cost in men and money, and all its military and political mistakes, the great Frontier War of 1897 has at least shown on what foundations the British rule in India rests, and made clear who are our friends and who our enemies.

I could not help thinking, that polo has had a good deal to do with strengthening the good relations of the Indian princes and the British officers. It may seem strange to speak of polo as an Imperial factor, but it would not be the first time in history that national games have played a part in high politics. Polo has been the common ground on which English and Indian gentlemen have met on equal terms, and it is to that meeting that much mutual esteem and respect is due. Besides this, polo has been the salvation of the subaltern in India, and the young officer no longer, as heretofore, has a “centre piece” of brandy on his table night and day. The pony and polo stick have drawn him from his bungalow and mess-room, to play a game which must improve his nerve, his judgment and his temper. The author of the Indian Polity asserts that the day will come when British and native officers will serve together in ordinary seniority, and on the same footing. From what I know of the British officer, I do not myself believe that this is possible; but if it should ever came to pass, the way will have been prepared on the polo ground.

The camp of the 3rd Brigade was not attacked again. The tribesmen had learnt a bitter lesson from their experiences of the night before. The trenches were, however, lined at dark, and as small parties of the enemy were said to be moving about across the front, occupied by the Queen’s, there was some very excellent volley firing at intervals throughout the night. A few dropping shots came back out of the darkness, but no one was the worse, and the majority of the force made up for the sleep they had lost the night before.

The next morning Sir Bindon Blood, his staff and three squadrons of the 11th Bengal Lancers, rode back through the pass of Nawagai, and joined General Jeffreys at Inayat Kila. The 3rd Brigade now left the Malakand Field Force, and passed under the command of General Elles and beyond the proper limits of this chronicle; but for the sake of completeness, and as the reader may be anxious to hear more of the fine regiment, whose astonishing fire relieved the strategic situation at Nawagai, and inflicted such terrible losses on the Hadda Mullah’s adherents, I shall briefly trace their further fortunes.

After General Wodehouse was wounded the command of the 3rd Brigade devolved upon Colonel Graves. They were present at the forcing of the Bedmanai Pass on the 29th of September, and on the two following days they were employed in destroying the fortified villages in the Mitai and Suran valleys; but as these operations were unattended by much loss of life, the whole brigade reached Shabkadr with only three casualties. Thence the Queen’s were despatched to Peshawar to take part in the Tirah expedition, in which they have added to the high reputation they had acquired in the Malakand and Mohmand Field Forces.