The Weimar Years – Part IV – Timeline from the Armistice to the Weimar Constitution

Editor’s Note: This is composed by our good friend Sulla.

November 12

- The Council of People’s Deputies announces elections for a new assembly taking place on the 19th of January with a new constitution promised.

November 15

- A pact is reached between Labor and Capital, and a collective bargaining agreement is accepted, providing for a continued free market, but also the recognition of Workers’ Councils. The Spartacists denounce this as a betrayal of workers’ rights and the socialist revolution.

Late November – Early December

- Marxist elements and Ebert’s centrist government continue to argue and maneuver, with the Marxists trying to establish a government based on Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils (e.g. Soviets), while Ebert continues to push for the democratic elections of the new assembly. The Spartacists and Revolutionary Shop Stewards vow to stop the elections.

December 6

- The Spartacists lead a march towards the center of Berlin and are confronted by troops who open fire, killing several demonstrators.

December 16 – 21

- The Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils is held in Berlin with 500 delegates from all over Germany. The Revolutionary Shop Stewards denounce the USPD for collaborating with the SPD. A Spartacist delegation forces its way into the meeting, spouting typical Marxist slogans and calling for typical Marxist claptrap. Various motions are argued back and forth, but the MSPD comes out victorious in the voting, winning their major provisions by 450-50 votes.

December 23

- 3,000 left-wing sailors (mutineers) abduct and hold hostage the MSPD military commander of Berlin over a pay dispute. The mutineers have already occupied the Hohenzollern City Palace. They march to the Chancellery and cut the phone lines. But they don’t know about the hotline between Ebert and Groener. Ebert calls Groener and requests help. Meanwhile, Emile Eichhorn, a USPD Reichstag member and the Chief of Police for Berlin, sends the Berlin Security Guard to help the sailors.

December 24

- “The Battle of Christmas Eve” sees a regular army division open fire on the rebel sailors and Berlin Security Guard in the City Palace. Several are killed on each side before a cease fire is reached, but this is something of a defeat for the regular army, and it is used as a propaganda win by the Marxist elements against Ebert.

December 27

- The USPD deputies, Haase and Barth, send a letter to the central council asking if they support the use of the army to suppress the revolutionary sailors. The council unanimously supports Ebert.

December 30

- The Spartacus League begins its two day National Congress in Berlin. It repudiates the USPD, and debates what to do about the upcoming elections which they have been unable to stop. Luxemburg argues they should participate in them, but the majority reject her proposal and choose to boycott the elections and instead organize an armed coup to bring down the Ebert government. Before ending the congress, the delegates vote to change the name from The Spartacus League to the Communist Party of Germany (KPD)

1919

January 3

- USPD members of the Prussian government all resign in protest.

January 4

- Paul Hirsch, Prussian Prime Minister dismisses Emil Eichhorn (a USPD member who had occupied police HQ, declared himself Chief, and later sent security forces to aid the sailors in the Christmas Eve battle) as Chief of the Berlin Police. Eichhorn is also accused of infiltrating the Berlin Police with members of the Revolutionary Shop Stewards.

- Eugen Ernst (moderate member of the SPD) is nominated to replace Eichhorn. It is unclear if this is a move by Ebert attempting to forestall a coup against himself by the radicals, or if it is a ploy to provoke the radicals into armed revolt before they are ready.

- A meeting of the USPD and Revolutionary Shop Stewards later that day announces a protest for the following day, with various workers and soldiers invited to it. A joint proclamation accuses the Ebert government of being “counter-revolutionaries” over Eichhorn’s removal.

- The KPD (née Spartacus League) agrees to attend the demonstration, but warns that an armed revolt against the Ebert government will end in failure.

January 5

- 100,000 workers attend the demonstrations in Berlin, occupying newspaper offices and government facilities. Eichhorn refuses to leave his office. At Police HQ, Liechtenstein gives a rabble-rousing speech, calling for more “revolutionary struggle.”

- Later that evening, the left-wing rebels meet. Encouraged by the size of the demonstrations, they decide to attempt an overthrow of Ebert’s government by armed force. A Revolutionary Committee is formed, led by Liebknecht, Paul Scholze (Revolutionary Shop Stewards), and Georg Ledebour (USPD).

- Ebert’s government sends pamphlets calling on workers from all over Germany to come to Berlin to protect the government from the “armed bandits of the Spartacus League.”

January 6

- The Revolutionary Committee issues a decree calling for the workers in Berlin to “bring the revolution to fulfillment” and overthrow Ebert. Again, 100,000 workers show up, outside the Berlin HQ. Many are armed this time, waiting for instructions from the Committee.

- Thousands of other workers respond to the Government’s call and show up outside the Reich Chancellery building. Scheidemann addresses them from a balcony, encouraging them.

- Ebert later holds a meeting of the Central Council and says military measures to put down the revolt are necessary. Gustav Noske is put in command of the government’s troops in Berlin.

- Noske drafts in the paramilitary Freikorps, conservative veterans who hate the communist radicals.

- The Revolutionary Committee meets all day and through the night, but comes up with no plans or instructions for the armed mob that has assembled.

January 7

- With no instructions, communication, or coordination from the Revolutionary Committee, the mob goes home.

January 8

- The Revolutionary Committee releases a vacuous exhortation to fight against the counter-revolutionaries, but gives no instructions and provides no leadership. This is its last leaflet.

- The Ebert government forms an auxiliary corps to protect government buildings in Berlin and issues a statement that the government is taking all measures to “destroy this rule of terror, and prevent its recurrence once and for all. Decisive action will be forthcoming soon.”

January 9

- The Revolutionary Committee holds the last of its meetings, and the KPD withdraws from it.

January 11

- Freikorps units, using artillery, force the occupiers of the Vorwärts newspaper building to surrender. The Freikorps kills seven of them on the spot and arrests the remainder.

January 12

- The revolution has been put down, with 130 to 200 revolutionaries killed vs. 17 Freikorps. Another 400 revolutionaries are arrested. Noske leads a victory parade.

January 15

- Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, and Wilhelm Pieck are arrested by a Citizen’s Guard in the Wilmersdorf district of Berlin and handed over to the Freikorps for interrogation. Enhanced interrogation, of course.

- Luxemburg and Liebknecht are shot and killed later that night, with their bodies dumped at different locations around Berlin. Pieck has managed to escape, though there are persistent rumors he had cut a deal and ratted out other rebels.

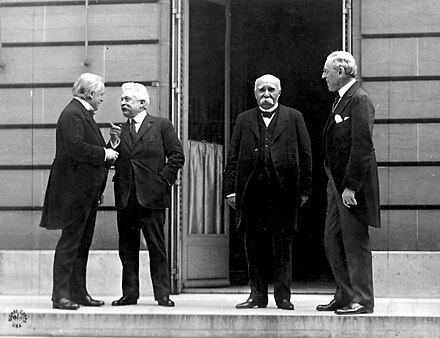

January 18

- Peace treaty negotiations begin.

January 19

- Elections for the new National Assembly are held, the voting age is reduced from 25 to 20, and women are allowed to vote for the first time. The SPD gets the most votes and forms a coalition government with Zentrum (Catholic Central Party) and the German Democratic Party (DDP, the old Progressive People’s Party plus the civil liberties wing of the National Liberal Party). Turnout is 83%. USPD – the far left – gets less than 8% of the vote.

February 3

- The Workers’ and Soldiers’ councils, recognizing the overwhelming opposition to left-wing radicalism, hand over their powers to the new National Assembly.

February 6

- Freidrich Ebert opens the first meeting of the National Assembly in the city of Weimar, which has been chosen because it is thought Berlin is still too unstable to host the meeting. The first order of business is the official name of the new republic, but the vote is to keep the name of The Deutsches Reich, or German Empire, instead of changing the name to the German Republic.

February 11

- The National Assembly elects Ebert as the first President. Ebert calls Freedom and Law twin sisters, and says one cannot exist without the other. He appoints Scheidemann as Chancellor, and declares the government will be a provisional government until a new constitution can be adopted.

February 12

- Corporal Adolf Hitler is reassigned to guard duty in Munich.

February 21

- Kurt Eisner, self-styled Minister-President of Bavaria since leading a left-wing revolt that deposed the King of Bavaria in November, is gunned down – shot in the head and back – while walking to parliament in Munich. His assassin is Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley, a 22 year old university student who had been a Lieutenant in the Royal Bavarian Infantry. An Austrian citizen from a wealthy Jewish banking family (mother’s name, Oppenheim), Arco-Valley is associated with right-wing nationalists. Despite his mother’s Jewish family, he is a self-proclaimed anti-Semite. Wounded in the attack, he expects he is going to be killed. Because of this, he leaves a note explaining his reasons for assassinating Eisner.

- “My reason? I hate Bolshevism. I love my Bavarian people. I am a faithful royalist, a good Catholic. Above all, I respect the honor of Bavaria. Eisner is a Bolshevist, he is a Jew, he isn’t German, he doesn’t feel German, he is betraying the Fatherland.”

- In Eisner’s briefcase was a speech announcing his resignation after his party’s (USPD’s) poor showing in the elections, having gotten less than 5% of the vote.

- The announcement of the assassination sparks a riot in the Bavarian Parliamentary chamber. One of Eisner’s supporters fires several shots (with a Browning pistol, no less) at the SPD leader, seriously wounding him. Two other members of parliament are killed when other supporters of Eisner open fire.

- The SPD declares the People’s Republic of Bavaria and suspends Parliament. Johannes Hoffmann forms a cabinet, but is unable to restore order.

February-March

- The formal government of Bavaria has effectively ceased to exist. Riots continue throughout Munich. A Central Council organized by Ernst Niekisch – formerly a colleague of Hoffmann in the SPD – declares the Bavarian Soviet Republic, opposed to Hoffmann’s government.

- Hoffmann and his government flee Munich for Bamberg, after receiving assurances of support from Scheidemann’s central government in Berlin.

- Mein Kampf makes little mention of this time.

February 26

- Eisner’s funeral draws thousands. Corporal Hitler marches in the procession.

March 7

- Corporal Hitler has likely already been recruited as a Reichswehr informer on the left-wing revolutionary movement in Munich.

April 3

- Corporal Hitler is elected as his battalion’s representative the to Munich Council Soviet.

April 6

- A group of anarcho-socialists declare the Munich Council Soviet Republic and seize power in the city. It is a collection of poets, romantics, intellectuals and dilettantes, led by Ernst Toller, a 25 year old poet and playwright from the USPD. This government is highly ineffective, staffed not just by silly dreamers, but legitimate mental patients. It is dubbed “the Regime of the Coffee House Anarchists.”

- Among other proclamations, Toller decrees an end to private property, and free education at Munich University, but bans the study of history.

April 13

- Toller’s Coffee House Anarchists are overthrown by the Palm Sunday Putsch, led by a Russian veteran of the 1905 Russian failed revolution, Eugen Levine. Rudolf Egelhofer, recruiting the Bavarian Red Army from factory workers, deposes Toller.

- Corporal Hitler counsels his fellow soldiers not to take sides in the Putsch.

April 18

- Hoffmann’s forces, badly outnumbered, are defeated outside Munich at Dachau by communist forces. Hoffmann requests the central government in Berlin help him put together an army to retake Munich. The response is a combination of regular army and Freikorps formations – including Freikorps Epp, a particularly effective and brutal unit led by General Franz Ritter von Epp. (Future Nazi party bigwigs Ernst Rohm and Rudolf Hess were members of Freikorps Epp). Overall command is by General Burghard von Oven (no, seriously, von Oven).

April 26

- Munich Communist rebels capture several members of the Thule Society, a somewhat mystical, secretive group that is anti-Communist and anti-Semitic, and believes in an Aryan Master Race. Their symbol is… of course… a swastika. Most of those captured are aristocrats.

April 30

- The Thule Society hostages are executed, in reportedly brutal fashion.

May 1

- The Freikorps leads the assault to retake Munich, showing no mercy to communists and communist supporters because of outrage at the Thule Society executions. The attackers use artillery, machine guns and flamethrowers in street-to-street fighting.

May 6

- The Munich Soviet government is thoroughly defeated by the German regular army units and Freikorps. The Freikorps then begin executing communists throughout the city. Eugen Levin is arrested, condemned to death for treason, and later shot. Egelhofer is shot on the spot by Freikorps members when they find him. General von Oven declares Munich secure.

- The short communist rule in Bavaria has been terrible, both brutal and ineffective at the same time (as all communist regimes ultimately are), but with the ineptitude and terror condensed into a span of weeks instead of decades. Bavaria, after this experience, is now home to the anti-communists.

May 7

- The draft Treaty of Versailles is presented to the German government. The terms are atrocious.

May 9

- Corporal Hitler is named to a three-man anti-communist board for his regiment, charged with investigating the political activities of soldiers in the regiment during the socialist takeover of Bavaria.

May 28

- Doctor Magnus Hirschfeld, a gay Jewish physician and “sexologist” debuts the film “Different From The Others.” It features a gay relationship between a teacher and a student, along with blackmail from a gay prostitute. The film is perhaps the first motion picture ever made with an openly gay character. It is a propaganda piece, arguing for the repeal of anti-sodomy laws. This film is often held up as characteristic of Weimar culture – as a positive by those who celebrate Weimar’s degeneracy, and as a caution by those who do not.

June 5-12

- Corporal Hitler, now working as a propaganda agent for his Reichswehr unit in Bavaria, is sent to a training course on political indoctrination. During the course, the student Hitler is noticed by the course director as a natural public speaker. Hitler is then made a speaker.

June 20

- Scheidemann decides he cannot sign the Versailles Treaty and resigns as Chancellor.

June 28

- The Treaty of Versailles is signed.

July 6

- Hirschfeld – the gay Jewish sexologist who created the gay film “Different From The Others” – opens the Institute of Sexual Science in Berlin. This institute “pioneers” hormone therapy and sex reassignment surgery, including the first recorded male-to-female genital mutilation surgery in 1920. The Institute also “studies” cross-dressing and provides counseling and networking for gays.

July 31

- The new Weimar Constitution is ratified.

August 11

- The Constitution is signed by President Ernst and goes into effect.