Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 19 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 18: Return to Bataan)

_____________________________________________________________________________

“If the majesty and power of Our Empire be imperiled, you must share with us the sorrow…”

(from a Japanese Imperial Rescript)

_____________________________________________________________________________

When we hit Corregidor’s Black Beach with the first wave, not much happened. Through a scattering of rifle fire we streaked across the chewed-up sands and on up the rock-bound side of Malinta Hill, knocking off a handful of Japs on the way. We dug in on that hill and there were a lot of Japs and guns and dynamite in the tunnels beneath us. We had occupied the height that divides Corregidor in two like a buckle on the belt around the waist of a big-breasted woman, and we had not lost a single man. Captain Frank Centanni, commanding “K” Company, looked around.

“I’ll be damned,” he said.

Before two days had passed that captain of ours was dead and covered by enemy fire so that we could not even recover his body. The hill was full of howling Japs and battle noise that’ll ring in my ears as long as I live. The tunnels below us turned into belching volcanoes and the limestone rocks dripped with American blood. A hundred and sixty-one of us moved in. Ninety-three came out. “K” stands for “King” Company, though when we got through we felt more like kindling wood than kings.[1]

We knew what soldiers can and cannot do. War had thrown us together whether we liked it or not; and war had crushed our illusions into the mud. We slugged it out with the Jap in Hollandia. We killed and buried him wholesale on Biak. We fought for seventy-eight days straight on Leyte. We led the drive into Bataan and we caught hell at Zig-Zag Pass. Right after that we were alerted for the storming of Corregidor. To every one of us still alive Corregidor is not a spot of glory, but the echo of a nightmare in hell.

The “Rock” did not look good to us even on the map. We knew that we were heading for one of the toughest jobs in any war. We were going to have help, but it was one of those combinations that has to work perfectly, or end in disaster.

“K” Company moved into Mariveles at the southernmost tip of Bataan on the day the 151st Infantry carved out a beachhead there. We came ashore wading hip-deep with rifles held high.

Mariveles. It’s the spot where MacArthur’s men made their last heart-breaking stand before the men of Nippon hoisted the rising sun banner over Bataan. It’s the spot where the “Death March” began. Remember? All the same, the guys on the beach of Mariveles were in no mood to dig back into history. All of us were looking down the inlet and out across the maw of Manila Bay. The sun glowed low on the horizon, blood-red. Out there, five miles to the south, Corregidor lay brooding in the twilight.

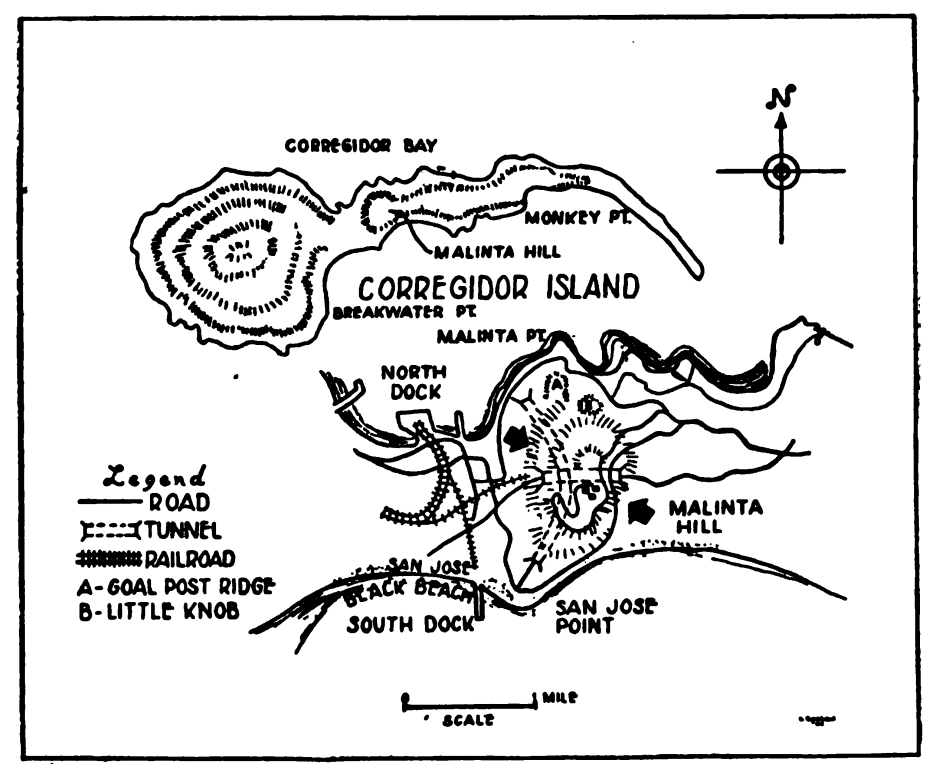

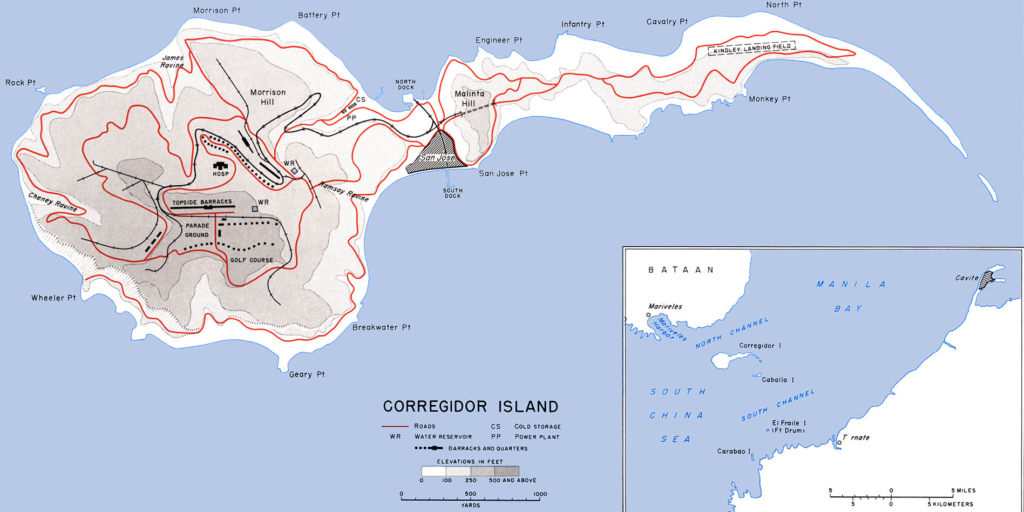

How we studied that Rock! Its massive western half, called Topside, lay on sand-colored cliffs thrusting out at Battery Point. A low, slim saddle — the woman’s midriff — led over from Topside to jutting Malinta Hill, which in turn was fronted by a promontory called Malinta Point; and tapering eastward from Malinta Hill lay the other half of the island: Engineer Point, Artillery Point, Infantry Point.

Our mission was to take Malinta Hill and cut the island in two: keep the Jap forces in the east from interfering with the cleanup of the Topside massif in the west— the paratroopers’ play. We didn’t envy them. The longer we looked at Malinta’s ramparts the more the hill seemed to us a furuncle ready to spurt poison under the push of a finger. The battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Edward M. Postlethwait (Warren, Minnesota), was looking, too.

“I hope it works,” he said.

We dug holes in the sand and slept as soldiers sleep — dropping off quick, but alert to the softest call. The clatter of machinery nearby did not disturb us. Somebody was loading assault equipment into landing craft: tanks, tank-destroyers, bulldozers, ambulances, a big truck loaded with TNT. That was for blowing up the tunnels.

The usual number of little things happened. One of the tank destroyers broke an oil line. It stuck lopsided in the surf. There was a flurry of curses and a clanking of chains. The thing would not budge. They borrowed another from the 151st.

We were awakened at 0530. A good wind rustled through the scrub and the night was full of stars. Already it seemed hot. Just fastening the pack and opening ration tins in the dark brought out the sweat. Loading began a half hour later.

One by one the landing craft pulled up to Mariveles jetty. Troops filed aboard, quiet and orderly. The rifle squads. Machine gun crews and mortarmen lugging their weapons. Bazooka-men with their stovepipes across their shoulders. Flamethrower operators glum under the weight of their tools. They climbed aboard and squatted, tightly packed. Each man packed grenades, atabrine and two canteens of chlorinated water. Smoking was out until daylight.

Last in, first out. “King” and “Love” Companies loaded last.

Dawn broke, pearly and big. Wind clouds stood over the horizon. Corregidor lay as silent in the twilight as a huge tomb. By now the Japs were watching us through their glasses. Some of us lit cigarettes. Light was passed around to others. You could feel the fellows wondering what yonder Japs were cooking up for our reception. The wind blew from the south. Some thought they could smell Nips five miles away.

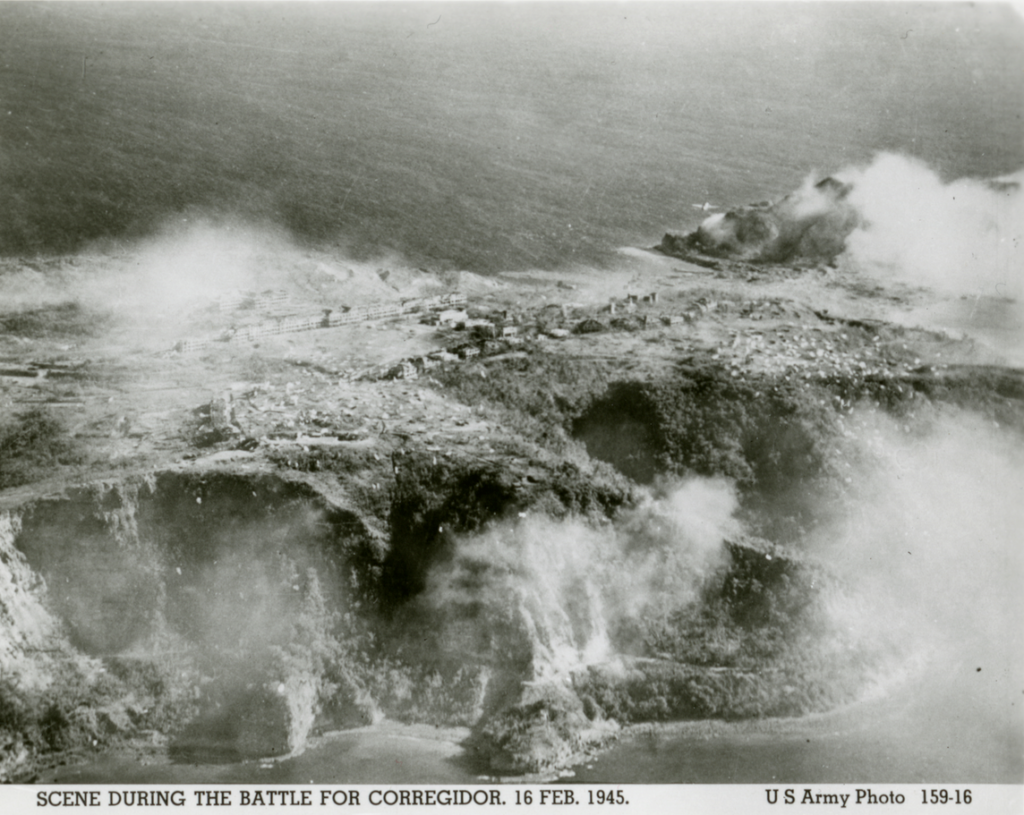

The sun came up and the boats vibrated with the steady rumbling of their engines. As we moved out — very slowly — small dots drifted up with the wind, came nearer, became formations of bombers. We saw them circle the Rock, lazy-like and distant. Over the white-yellow cliffs of Corregidor blossomed sudden little shapes, like flowers pushed up out of a magic garden. Petals of smoke; bombs bursting. Soon the planes were as thick as sail boats at the starting line of a regatta. We looked for ack-ack, saw none.[2]

Rolling across the bay was the thunder of many explosions.

Warships appeared and moved in close. Steel pitched into the Fortress’ gun positions. The cruisers and destroyers were as casual about it as the planes. By 0800 a heavy pall of smoke covered the island. Peering over bulwarks as we drew closer it seemed to us that every foot of surface up there had been put through a giant sausage grinder. The smoke was so dense that we could not see the flashes of bombs and shells striking home. Diving planes vanished in the black welter and then zoomed out of it with screeching motors.

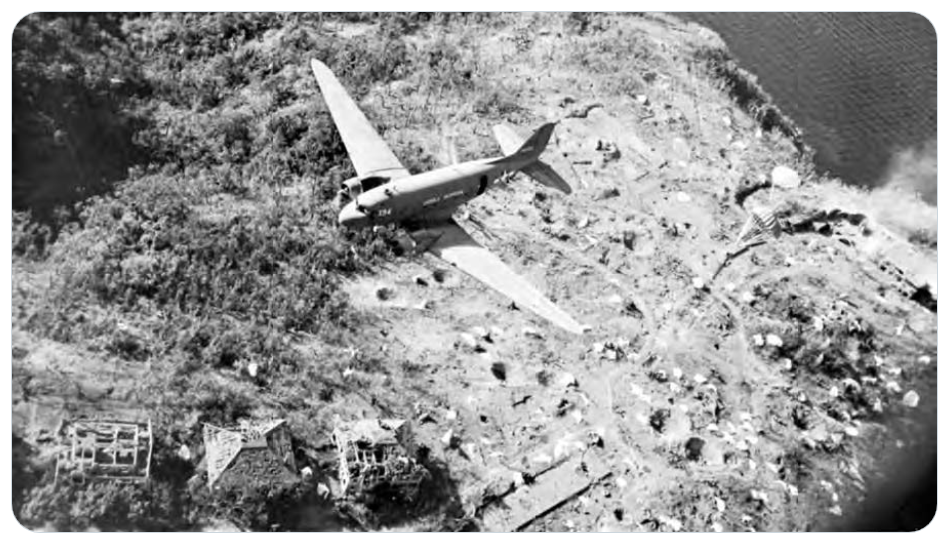

0830: another series of dots drifted up from the south. They came in fat formations and slower than the bombers. They were black planes, transports loaded with paratroops. They lower their flaps and barely maintain flying speed when they drop their men. In twos and three they floated in over the Topside plateau and paratroops floated out. Cross winds gave trouble. Many troopers came to grief on the cliff sides. But most dropped out of sight into the smoke.

We waited and listened, but everything seemed quiet up there. We had been circling all this time through choppy seas and now hovered off the southern beach which links the tunnels of Malinta Hill with the Topside forts. Black Beach this strip of sand was called. It lay open to crossfire from the flanking heights. We ducked and sucked in our guts as the motors pounded into high. The rocket ships cruised in close, pasting the cliffs as they went. Then we made the run.

We hit the beach two platoons abreast on a two-hundred-yard front. The ramps creaked down and we rushed ashore — through swarms of big, blue-bodied flies. Millions of flies.

At this spot the island is only five hundred yards wide. The sand was churned into an irregular pattern of craters. A band of land-mines followed the water’s edge and another band of mines lay parallel to it some thirty feet inshore. Some of the mines were connected by trip wires which would set them off if somebody stumbled. We kept going fast, leaping across the mines and the wires and holes in the sand.

There was a fantastic silence. The engines of landing craft chugged to keep their boats’ snouts anchored to the beach. Shouted commands sounded silly in the stillness after the barrage. The bombs and shells and the rockets had driven the Nips from their guns. A spattering of rifle fire welcomed us. That was all.

We double-timed through sand and flies. The morning sun was blazing. We traversed a belt of what had been concrete buildings. The buildings were razed. There wasn’t a piece of wall more than a foot high. The rubble lay not in piles, but scattered and flattened in crazy confusion. We dashed across that. About two hundred yards inland we swerved to the right on up the cliff-like face of Malinta Hill. We climbed like hell-bent apes.

Once on top we felt pretty lucky. Violence rocked the beach behind us. Recovered, the enemy had remanned his guns. Right and left the hillsides spewed fire. Fifties tore through the landing craft and thirties hammered the plates and the ramps. Mines popped. Pieces of jeeps and tanks and tank-destroyers were flying in the sunshine. But a tank and a self-propelled gun crawled up the beach and plugged away at the pillboxes.

It was a tough climb up Malinta Hill. Mostly we were on hands and feet, like goats. The equipment on our backs seemed to weigh a ton. The company commander sent the Third Platoon around to the promontory called Malinta Point, just north of the big hump. The rest of us kept going, three hundred feet up.

We saw a tunnel entrance with a sand bag barricade. That was the Hospital Tunnel. One squad went over and fired rockets to neutralize Jap guns in the tunnel mouth. Two squads took position just above the entrance to watch it. Their business was to keep the Japs inside or kill them if they came out. There was a cave halfway up, just off the trail. A squad was sent to clean it out. The cave was empty. We gained the top without losing a man.

Except for a mat of sun-scorched grass and thin bushes the summit was bare. Not a speck of shade. Protruding from the crumbling limestone were the vents for the tunnels below. “Grenades!” Our men pulled pins and dropped grenades down the shafts. The bursts were muffled and far away. Then there was a yell and some shooting. Someone had found a cave and in it was a large searchlight. Behind the searchlight crouched four Japs. They squealed and died.

Meanwhile, the Third Platoon kept moving north toward Malinta Point. They rounded a curve of rock and met fire from the Hospital Tunnel. They slithered past in a hurry, leaving those tunnel guns between themselves and their battalion. They darted through the rubble of ruined buildings and came face to face with the mouth of another tunnel — this one opening to the northwest. They fired bazooka rockets into the tunnel and hurried on their way. They reached Malinta Point and spotted a few Japs in a cave. The Nips vanished in the inside of the cave, leaving three anti-aircraft guns at the entrance. Our men kicked over the guns and left a patrol to cover the cave. The rest climbed up Malinta Point and dug in — as much as you can dig in hot rock.

Malinta Hill was unnaturally quiet. The top was covered with big, blue flies. The flies buzzed around us like locusts. A hundred pounced to suck your sweat for every one you killed.

Down on Black Beach things did not go so well. A tank was knocked out by a mine. A tank-destroyer went to hell. An anti tank gun, the jeep that pulled it and the men in the jeep were blown in all directions. “Mike” Company was hit in the boats before they reached shore. Nip machine guns fired from San Jose and from Breakwater Point. “Mike” Company lost more men by mortar bursts as they raced up the beach. More steel killed two staff officers. “Item” Company rushed across the narrow middle of the island toward North Dock. More ships, more men kept coming ashore. You could see them unload their ships under mortar blasts and you wondered how they got away with that. Fire from the Hospital Tunnel under Malinta Hill was heavy. The Hospital Tunnel was the biggest of all the tunnels. It’s the spot from which General Wainwright surrendered to the Japs three years before.

Down there on the sweltering beach Captain Joe Richards (Portales, New Mexico) walked around collecting his scattered squads. Corpsman Sam Schneiderman (Bronx, New York) was squatting under machine gun fire, trying to patch up an officer, who got it badly. Another aid man, Florian Bauman (Buffalo New York) maneuvered a jeep full of medicines and plasma through the mine belts. Two supply boats were driven twice off the beach by enemy fire. The coxswain of one was killed. The captain of the other was hit and so were fifteen men on the boat. Corpsman Raymond Backlund (Chicago) jumped around, stopping blood-flow and treating the hit men for shock. Backlund brought one of the boats inshore and helped to unload it, with lead slapping the sand around him.

Jerry Rostello (Haledon, New Jersey), a motor sergeant, had his leg mangled by shrapnel. All the same he kept moving, pulling dead men out of jeeps and trucks among the mines, and getting the trucks to a safer place. Lieutenant Pete Slavinsky (Kulpmont, Pennsylvania) was busy mounting machine guns at the edge of the beach. Corpsman Harold Asman (Braddock, Pennsylvania) lugged wounded buddies down the sheer slope of Malinta Hill. So did Aid Man Russell Hill (Bartenville, Illinois). They bedded the wounded on litters in the sand, and applied the splints and the tourniquets and the bandages, sulfa and morphine, ducking the bullets and fighting off flies all the while. Sergeant Don Wood (Reedy, West Virginia), one of the best mortarmen in the world, saw four Japs toss grenades from a shell crater. He killed two of them with his rifle.

Two landing craft loaded with vehicles hit the beach and all vehicles promptly hit mines and blew up. Lieutenant Bill Skobolewsky (Nanticoke, Pennsylvania) went to work marking out a safer path among the mines. He took the chance of machine gun bullets setting off the mines around him. He crawled from mine to mine and marked them with little sticks and after that he marked out a path through the mine field with white tape. They later counted the mines he had marked — there were 216.

On top of Malinta Hill the strange quiet lasted all afternoon. “King” Company held the north end of the hill. “Love” Company occupied the southern hump. From where we sat the whole island lay beneath us like a living map. Everywhere was smoke and commotion except on top of Malinta Hill. But the heat and the flies gave us a hard time. Besides, a man feels peculiar when he knows that the insides of the hill on which he sits are jam-packed with Japs and dynamite.

Our mission was to keep the Japs in the tunnels; to let no Japs run from one end of the island to the other. To make the block complete, two squads pulled out to occupy two rises in the ground between us and the Third Platoon on Malinta Point. On one of these knolls the men found a cable hoisting contraption which resembled a football goal post. They called it Goal Post Ridge. Let’s call the other one Little Knob.

Three men were sent to block the road which runs east-west past Malinta Point. These men stayed at their post for eight straight days under almost unbearable conditions. They stayed there from February 16 to February 23. They fought off eight night attacks in this time. In the eighth attack they killed twenty-three Japs who tried to Banzai them with rifles, bayonets, pistols, sabers and grenades. Each of these three men lost twenty pounds in a week. You should know their names. They might mean little to you, but they mean a lot to us: Sergeant Lewis Vershun from Britton, Michigan. Private Emil Ehrenbold from Hutchinson, Kansas. Private Roland Paeth from Bay City, Michigan.

To get back to Malinta Hill: That first afternoon we strung telephone wire from Malinta Hill to Malinta Point by way of Goal Post Ridge and Little Knob. Nothing more was to be done than to watch the fighting on the beach below, and to join in once in a while with a burst when Japs poked their heads out of the tunnels. By 5 P.M. most canteens were empty. Some grumbled about their thirst. So came darkness.

The silence was torn asunder by a burst of firing just before midnight. First there was rifle fire and the rapid stuttering of Tommy guns, then the pounding of heavy machine guns and the thumping of mortars. Shouts and the sound of men scrambling over rocks somewhere downhill. The wires were cut and communications with the Third Platoon went out. Mortar fire fell on Malinta Hill. Around us and among us jerked the glares of bursting shells. Men were hit. Medics were busy. We could see nothing.

A voice growled, “Something’s climbing up the hill.”

Through the commotion came a crunching of footsteps, a panting and groaning.

“Let ’em have it.”

“Hold your fire.”

An angry whisper in the dark. Someone sobbing with pain.

Laboring up from Little Knob was Private Rivers P. Bourque of Delcambre, Louisiana. He had thrown away his pack but he still had his rifle. On his back he carried a comrade whose leg was shattered. Every few steps he halted to help a third man along whose hand was dripping blood. We dragged them up the last yards.

‘What’s wrong down there?”

Bourque sat down. He stared at the ground and panted. Jap mortar fire beat a witches’ tattoo. Malinta Hill and all Corregidor blurted battle.

“Down there — We’ve got to send them help.”

“What’s going on?”

“Surrounded…”

Through stabbing flame and flying steel Bourque’s words drifted like a faint dirge. His squad had spotted an enemy force deployed to push through between the ridges to attack the crowded beach. Bourque’s squad had opened fire with an automatic rifle, a Tommy gun and nine Garands. The Japs had rushed forward over their own dead. Grenades killed five men in Bourque’s squad. Four others were badly wounded. Two of the wounded had to remain behind, tended by Private Cassise of 3302 Canton Street, Detroit, Michigan. He had crawled through prancing death and given first aid to the wounded, then hidden them as best he could. Cassise was still down there among the Japs.

A little later came two men from the squad on Goal Post Ridge. They were cool and angry. They said the Japs had tried to storm Malinta Point. But the Third Platoon there had held out in good shape. On Goal Post Ridge things were different.

The Nips had swamped their squad in the dark and killed or wounded all but two.

To leave the wounded buddies behind them in the night had been the hardest task of their lives. But one infantryman had elected to stay with the wounded, to tend them and to defend them. That boy was Clarence Baumea, whose mother lives in Adrian, Michigan.

Much happened that night. Soldiers of one “Able” Company platoon, stationed near the water, saw a great hunk of the cliff above them lurch away and down in the dark. We all heard the deafening noise and wondered what it was. The Nips had mined the cliff with the idea of burying “Able” alive. But the Nips had filled the cliff so full of explosives that the mass of rock flew clear over the heads of the troops below and banged into Manila Bay.

Soon “Abie’s” riflemen heard splashes in the water. There were little whirlpools of phosphorescence. At first they thought it was porpoises gamboling. But they took no chances. They fired. They heard screams. It was a bunch of Nips trying to swim around San Jose Point with waterproofed packages of TNT strapped to their bellies. “Able” Company killed twenty-three of the swimmers.

A soldier checking a broken telephone wire slipped around a rocky nose and suddenly found himself in front of one of the tunnels. Nine Japs came popping out of the tunnel. The lineman, Jack Sparkman (Littlefield, Texas) backed off the way he had come. The Japs followed him, skirting the rock in single file. Jack Sparkman grew desperate. Finally he yelled,

“Ain’t there anybody who kin shoot those Japs?”

Gunfire from somewhere answered his plea. Sparkman heard the slugs whizz by his ears. They killed five of the Nips and the others dodged back into their tunnel.

Up the cliffs of Malinta Hill came two anti-tank gunners with water and ammunition. The water was for the wounded. Snipers took shots at the two as they climbed. The two soldiers crept from rock to rock, a few feet at a time. One pushed up their loads over his head and the other pulled them up with a rope. Corporal Nino DiGregorio (Wappingex Falls, New York) and Ptivate Francis Titus (Arcadia, California) made the trip four times. Each trip they carried back a wounded man, or rather lowered him down the hillside with ropes.

We on the hilltop felt bad about our wounded buddies on Goal Post Ridge and Little Knob. It’s the worst feeling in the whole world. The coward in you comes out. You want to go and you don’t. What if it were you?

We all wanted to get those wounded out. Our captain did too. But the odds were too great. He couldn’t risk any more men. His mission was to hold the hill. It was tough but that’s the way some hands are dealt. Then it was too late. Determined to clear the way to the beach the Nips now flooded out of the tunnels in force. They assaulted Malinta Hill.

The night exploded in fury and death. First came a concentration of mortar fire. Five men were hit by fragments from the “Flying Ashcans.” Then came the assault, in two waves a-churn with the insane savagery of a Banzai charge.

We let them come to within ten feet of the top. Then we opened up with all we had. It was like a massacre in a lunatic asylum.

The cliffside which the Japs scaled was so steep that the first who were hit fell into the faces of their fellows farther down. We sent scores of them rumbling down. Japs pitched end over end into the gorge below. The hillside seethed with Japs. Their mad yelling hurt our ears more than the blasts from rifles and machine guns. They kept coming. In close-in fighting one of our squads was pushed toward Goal Post Hill, ran into a solid wall of fire and lost five men, including its automatic rifle gunner.

There were shouting Japs ten feet from our perimeter. You could see them briefly in the blue light of flares: eyes gleaming under helmet rims, one hand grasping the bayoneted rifle, the other clutching a grenade. Some had double-barrelled shotguns. Corporal Daniel Smith of Bellevue, Pennsylvania, hurled grenades, saw them crumple a flock of Japs like paper dolls. Another Pennsylvanian, Private Adolph Neamend of Bethlehem, emptied his Garand into the wide-open mouth of a howling Jap, or so it looked. Another Jap tossed a grenade pointblank at Private Ray Crenshaw of Clinton, Oklahoma, and Ray kicked it aside and gave the Jap his due.

This fray lasted for an hour and a half. Don’t tell me the Jap is inferior. They were able and brave. But they, too, have their saturation point. They sank away in the dark and with them they took some of their dead. The rest of the night both sides licked wounds.

Sergeant Willard Harp from Durhamville, New York, and seven fellow medics piloted six of our litter cases down the cliffs and past the tunnel mouths. Corpsman James Carter from Ennenton, South Carolina, and another aid man rescued a wounded comrade who had fallen down the slope. On the way Carter’s companion was killed by a Jap machine gun.

Came dawn, and another fly-cursed day. The bodies of dead Nips hanging in the rocks below us began to smell soon after the sun came up. You could not see their faces for all the flies. Some wounded groaned, with the hot sun and the flies in their wounds, and we killed them to help them, but their smell became as bad as their groaning.

Malinta Hill was quiet. Elsewhere the fighting had picked up again after sunrise. Our captain dispatched an eight-man patrol to secure the wounded on Little Knob and Goal Post Ridge. We watched the patrol slide down the hillside and move past the harvest of cadavers. It reached Little Knob all right. One of the wounded men there was still alive. The others had died during the night.

The patrol regrouped and pushed toward Goal Post Ridge. They had not gone thirty yards before they met an ambush. Four men fell in a squall of bullets and grenades. The survivors fell back to Malinta Hill.

Our captain was gallant and humane. He could not sit still with the thought that there were wounded members of his team down there, helpless at the mercy of the Japs. He called for volunteers and he himself volunteered to lead the patrol.

We wished him luck. He grinned.

We covered them as they went down the slope. Crawling and creeping they proceeded to the point where the first patrol had met disaster. They passed that point without drawing fire. They had gone halfway to Malinta Point. Then lurking Nips opened up with rifles and lobbed grenades.

Captain Centanni was out in front. A bullet killed him where he stood. His men poured instant fire, killing four Japs. But three enemy grenades exploded almost on top of the captain. The men crept to within inches of their dead commander. But the Japs kept his body covered by fire and the boys couldn’t bring him back.

Sergeant Bill Scott (Garnett, Kansas) carried a wounded soldier from Goal Post Ridge to Malinta Hill. On the way he was shot by a sniper, but he finished his mission without asking for help.

Early that morning Jap demolition teams tried to sneak through “Mike” Company ranks to Black Beach. The machine gunners on the perimeter worked with carbines and grenades and fifty-nine Nips died in the rubble of flattened buildings. These Japs wore the uniforms of Imperial Marines. Some of them were armed with big, American-made shotguns shooting loads of rusty scrap.

The Japs had slipped out of one of the tunnels in Malinta Hill. A “Mike” Company platoon went out to seal the tunnel. The platoon was quickly surrounded by stronger Japanese forces. Mortars were needed to blast them out of the trap. Sergeant Marion Veal (Hardwick, Georgia) clambered over the rocks to Malinta Hill with a telephone and a wire line to a point from which he could see the Japs around the tunnel. Another observer laid another telephone wire up the western side of the hill. Three others had tried that before, and all three had been shot by a machine gun. Sergeant Arnold Kuyper (West Bend, Iowa), did the job in good shape. After that the mortarmen laid their eggs true among the Japs.

Down by the North Dock, “Item” Company platoons dug and blew and burned the enemy out of a dozen holes and caves. After a hard day’s flamethrower work their score was thirty-one.

“Able” Company soldiers accompanied some tanks which battered the entrance of the Hospital Tunnel. They helped to keep a host of Japs inside and stewing.

“Love” Company dispatched a patrol with a trunk full of TNT to blast two caves on the eastern side of Malinta Hill, just below the crest. The first cave was quickly sealed with the Japs chanting inside. The patrol then moved to the second cave and installed the rest of the TNT. The charge was too big. Instead of being sealed by the blast the cave was blown wide open. The Japs rushed out. Our sharpshooters cut them down.

After that the patrol found a field gun and knocked it out. This gun bore the marking: “Edgewood Arsenal.”

Sergeant Herman Taylor (Russellville, Kentucky) carried a load of fresh ammunition two hundred yards over the rocks. Lieutenant Kenneth Yeomans (West Somerville, Massachusetts) and his platoon specialized all day in fragmentation charges and white phosphorus grenades. They burned twenty-five Japs to death.

On the same day the commanding officer of the Division task force shook hands with the commander of the paratroopers fighting on Topside. It was like Stanley meeting Livingstone in the Congo.

It was now 1400 February 11, and the sun oozed heat. Gun barrels and helmets became too hot to touch. We kept wondering why it was so quiet on Malinta Hill. We also kept wondering what had happened to the Third Platoon, marooned out there on the promontory.

Contact was finally made by radio.

“This is Joe Blow to King Three. King Three, tell me your situation.”

“King Three to Joe Blow… We’re okay… Over,” they answered.

“Joe Blow asks have you had any trouble… Over.”

“Two attacks. We have three walking wounded. Not bad… Over.” –

“What are you firing at…? What are you firing at…? Over.”

At the other end somebody chuckled.

“Just good clean fun, we’ve got…”

The Third Platoon explained: They had a bead on a distant water well, on the eastern end of the island, and the Nips seemed to have become mighty thirsty. They kept dashing up to the well with jugs and the marksmen of the Third Platoon were picking them off.

“Good. Sit tight.”

“We’re sitting all right.”

“Roger — out.”

Orders were to hold Malinta Hill and the other position as bulkheads denying the enemy a pooling of his strength. Already our battalion was spread so thinly that no reinforcements could be spared for Company “K.” So we reorganized our decimated squads. We dug in deeper to meet another night. The sun beat down on us with devouring power. The pale rock reflected the heat and drilled it into our brains and bones. Some men collapsed. A few lost heart and hid their heads like whipped dogs.

We asked the battalion for water.

“No more water,” was the reply. Nips on a suicide mission had demolished the water purification units during the night. The nearest water was five miles away in Mariveles and must be transported by barge. More and more the belt buckle on the island-woman’s midriff — Malinta Hill — became to us the navel of a leprous whore. Another night towered over the mountains of Luzon.

Down near the beach a lone Jap with a mine crawled under the Red Cross wagon and blew up the wagon and himself as well. The Red Cross man came running. His wagon, his cigarettes, his soap, coffee, cokes, toothpastes and magazines were one big mush mixed up with minced Jap.

A mortar barrage fell at 2330. At midnight the Japs attacked. They threw in everything they had. Again they scaled that impossible cliff in a death-seeking, death-dealing frenzy. They had made up their stubborn minds to claw out a passage that would let them join their well trounced Topside garrison.

Lieutenant Albert S. Barham, a Texan from Eastland, was the first to hear them pussyfoot up the slope. Barham had won his commission fighting at Leyte. He launched some flares. The hillside swarmed with crawling shapes. We looked right into their faces, twenty feet below us. Our fire transformed their stealth into a crazy rampage. They were like demons running amuck, half tiger, half baboon.

I’ve never heard so many grenades thrown in so short a time. When we ran short of grenades, ‘Tex” Barham had been hit in the face. But he ducked through the uproar to where Company “Love” had its perimeter. I never saw a man sprint so fast on all fours. Sergeant Herman Taylor helped him. Soon they came back with more grenades. For this time the Japs had enough. They scrambled downhill and vanished in the dark. Some twenty of our men were hit. But we had killed plenty. One of the few who did not kill a Jap was Corporal Edward J. Stachelek of North Adams, Massachusetts. While grenade fragments and bullets ripped the night, he slipped from hole to hole to tend the wounded. Then he was wounded himself.

‘Take it easy,” we told him. “Let somebody else carry on.”

“No,” said Aid Man Stachelek, “my mission, ain’t it?”

And he went right ahead with sulfa and bandage kit, as did another corpsman, Frederick Lederer, who has a wife in Saint Joseph, Missouri.

Just then the moon rose over Manila Bay like a fine orange. It outlined our positions on top to observers around the base of the hill. Lying wounded in a foxhole, Lieutenant Henry G. Kitnik (Broughton, Pennsylvania) was swearing at the moon.

“Hank” Kitnik had taken command of “King” Company when our captain was killed by grenades. But “Hank” was hit in the back of the head and in the arm, and so another Pennsylvanian, Lieutenant Robert R. Fugitti (Philadelphia) took over.

Besides the indestructible Barham, Bob Fugitti had only one officer left, Lieutenant Albert J. Cruver of Seattle. Through the moonlight they crawled, counting the fit.

“How many in the Second Platoon, Al?”

“Eight,” reported Al Cruver.

“First Platoon?”

“Nine,” came a muffled reply. “Grenades are all gone.”

“Christ, what a mess.”

The Weapons Platoon reported only eleven men fit for action. Headquarters had ten: linemen, messengers, supply crew, cooks, all of them fighting with the rest.

Thirty-eight men and three officers to hang onto Malinta Hill.

“I’m going to get some more grenades,” Tex Barham an nounced—and off he went, bandaged head and all.

We pulled our men closer together to tighten up the mangled line. We waited through the longest minutes of the longest night that ever straddled the Philippines. A few canteens of water were carried up from the beach. The carrying party had trouble with snipers. Only the wounded got water. The rest of us chewed our tongues. A shadow bobbed up in the dark.

That was Barham, coming back with eight more grenades.

The minutes wore on.

“What time is it?”

“Same time as this time last night.”

“Hey, what time is it?”

“Oh, pipe down.”

“What time is it?”

“Banzai time.”

“Has anybody got the time?”

Every five minutes someone asked about the time.

The Japs attacked at 0300. First there was ferocious mortar fire, then the frantic yelling, the hot bloody sweat, the bullets and grenades, the kicks and cold steel, the wordless rage, the whole twisted monstrosity of killing in the dark. That went on for an hour before the enemy streaked back downhill where he belonged. Five more of our men were hit.

Again we reorganized, now thirty-three of us, sat tight, sweating out the dawn.

One hundred and fifty Jap cadavers stared up from the lime stone cliffside.

With daylight a carrying party came through with water and rations. They took away the wounded. Then another company relieved us and we dragged ourselves down to the sweltering beach. There was a bevy of medics dealing out “something to quiet your nerves.”

“Make mine rye,” cracked a kid with blood in his hair.

They gave us capsules.

We flopped into the sand and slept, sweating while we slept, with firing loud a couple of hundred yards away, among millions of flies and the stench of dead men decomposing in the sun. Warships stood offshore, shelling the cliffs around Breakwater Point.

The battle for Corregidor was not finished when we woke up to a meal of canned frankfurters, canned sauerkraut and dehydrated potatoes. The whole rutted island was still heavy with trouble.

‘Item” Company cleaned out the North Dock area for the second rime. One of the squads ran into grenade ambush among the rocks. Sergeant Owen Williams (Chicago, Illinois) cried a warning. The squad ducked and was saved. But Williams’ warning shout had given his position away. He dropped mortally wounded.

“Item” Company swept forward. They killed forty Nips and captured two machine guns.

“Love” Company men cleaned out caves and tunnel entrances around Malinta Hill. They blew up three naval guns mounted in rock bunkers. They also destroyed a huge fourteen-inch cannon. The men of “Love” changed the name of their company to “Lucky.” In five days of fighting on the hill they had not lost one man.

The Japs were still firing doggedly from Engineers Point. Elsewhere our tank-destroyers smashed pillboxes which the Nips had built in an old ice plant between Topside and the Hill.

At one time word came through that the portable hospital treating wounded paratroopers on Topside had used up all its plasma and whole blood and needed more. That hospital was two miles from Black Beach. Two men on a tank-destroyer volunteered to slug through with more plasma.

They stowed the life-saving stuff under their cannon and roared off along a winding road. Enemy machine guns near the ice plant beat against the armor of the SPM.

Through the sight slots of the tank-destroyer Sergeant Bill Hartman (Peoria, Illinois) and Corporal Mike Nolan (New York City) saw a shell-wrecked bridge ahead. The bridge lay askew and there was a jagged gap. Their self-propelled cannon weighed twenty-three tons.

“Give her the works,” said Hartman.

Either the bridge would hold, or it would not.

The tracks ground over the jagged gap, lapping over four inches on each side of the span. The bridge groaned — and held.

Past shredded clumps of vegetation and a line of pillboxes the tank-destroyer reached its destination. The medics took the plasma and hurried away. Others unloaded a few cans of water which happened to be aboard the mount.

“Sure wish you had brought us some more water,” a doctor said. ‘We’ve none up here.”

“We’ll bring it, Doc,” said Hartman.

The wrecked bridge groaned and held and the paratroopers got their water. Back on the beach Hartman and Nolan drove toward a gasoline dump to tank up. Before they reached it their motor bucked and stopped. A connecting rod had broken. Bill Hartman stood among swarms of flies and stared at his mount. Its name, big and white, was SAD SACK. Mike Nolan counted the bullet scars on the armor. He stopped after counting two hundred.

On February 19 our mortars put three hundred pounds of high explosive on Goal Post Ridge where our gallant captain had been killed.

February 20 we spent thinking up ways of finishing off the Japs in the big tunnels of Malinta Hill. We knew that there were hundreds of them holding out in the tunnels. At night they came out to raise hell; at dawn they crawled out of our sight and reach. We tried this and that, “Love” Company men threw smoke grenades into a tunnel in the hope that the rising smoke would curl from the air vent that serviced it. The vent could then be blocked and the Nips’ air supply cut off. But the smoke stayed in the tunnel. So did the Japanese.

There was a threat in the cavernous bowels of Malinta Hill that had us all on edge. A captured list of supplies in the Hospital Tunnel showed that there were stowed away inside the hill 35,000 artillery shells, more than 10,000 powder charges, more than 2,000 pounds of TNT, some two million rounds of rifle and machine gun ammunition, 80,000 mortar shells, more than 93,000 hand grenades, 2,900 anti-tank mines among many other parcels of war.

At 9:30 P.M., February 21, the Japs blew up Malinta Hill.

First there was a rumbling noise. It sounded like freight trains thundering beneath the rocks of Corregidor. Then there were mighty explosions and the island trembled. Sheets of flame shot from the tunnel mouths. Flames belched through the summit of the hill. A crumbling hillside buried alive an “Able” Company detachment on a roadblock below. Sections of road were blown out. Rocks and wreckage and clouds of Jap bodies sailed high in the mellow night. From other places Jap machine guns were firing wild into the flanks of Malinta Hill. About fifty Nips, in a column of twos, marched out of a tunnel as if they were on parade. Our machine guns mowed them down. Other Japs came dashing out of other tunnels. Our guns kept barking.

Two nights later they tried again. Rocks crumbled and fire belched from every hole in the rocks.

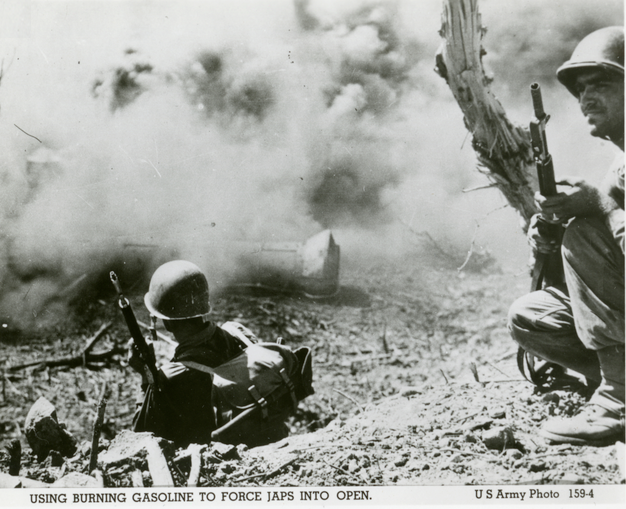

Our engineers went to work to carry the job to an end. Quantities of gasoline were set afire in the remaining tunnel mouths, and the entrances were then sealed by blasts. For days there came dimly out of the tunnels the sounds of shouting, of mass singing, of muffled pistol shots and grenade explosions. Then silence.

(Continue to Chapter 20: Thunder to Davao)

_____________________________________________

[1] Fortress Corregidor was invaded by a U.S. task force on the morning of February 16, 1945. The parachute invasion of the island’s “Topside” was accomplished by the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment. The invasion of the southern beaches of Corregidor was the work of the Third Battalion, reinforced by Company “A,” Thirty-Fourth Infantry Regiment, Twenty-Fourth Infantry Division. This narrative deals in the main with the activities of one company of the invasion force — Company “K.”

[2] Advance intelligence on Japanese armament reported 18 heavy coastal defense gun positions, 14 anti-aircraft installations, and countless caves and machine gun emplacements around Malinta Hill, San Jose and South Dock.

Interesting how the left has stormed America over the past 40 – 50 years. Right now, it’s only the academic version of Japanese occupation… totalitarian, foreign to American thinking, brutal reprisals for wrongthinkery. The rest will come.