Editor’s Note: This is the second chapter of William the Conqueror, by Jacob Abbot (published 1877).

II. The Birth of William

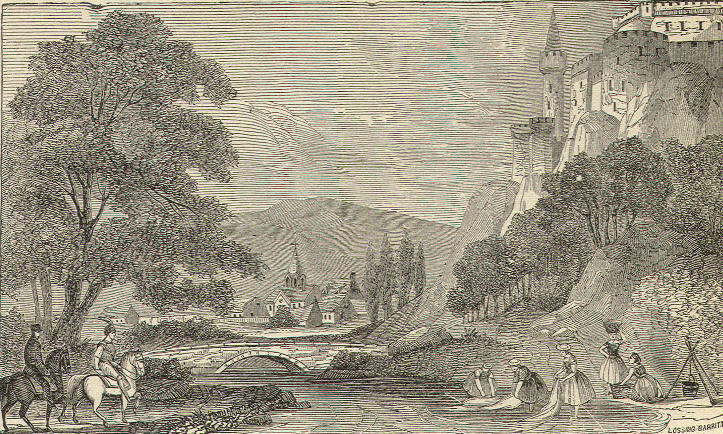

Although Rouen is now very far before all the other cities of Normandy in point of magnitude and importance, and though Rollo, in his conquest of the country, made it his principal headquarters and his main stronghold, it did not continue exclusively the residence of the dukes of Normandy in after years. The father of William the Conqueror was Robert, who became subsequently the duke, the sixth in the line. He resided, at the time when William was born, in a great castle at Falaise. Falaise, as will be seen upon the map, is west of Rouen, and it stands, like Rouen, at some distance from the sea. The castle was built upon a hill, at a little distance from the town. It has long since ceased to be habitable, but the ruins still remain, giving a picturesque but mournful beauty to the eminence which they crown. They are often visited by travelers, who go to see the place where the great hero and conqueror was born.

The hill on which the old castle stands terminates, on one side, at the foot of the castle walls, in a precipice of rocks, and on two other sides, also, the ascent is too steep to be practicable for an enemy. On the fourth side there is a more gradual declivity, up which the fortress could be approached by means of a winding roadway. At the foot of this roadway was the town. The access to the castle from the town was defended by a ditch and draw-bridge, with strong towers on each side of the gateway to defend the approach. There was a beautiful stream of water which meandered along through the valley, near the town, and, after passing it, it disappeared, winding around the foot of the precipice which the castle crowned. The castle inclosures were shut in with walls of stone of enormous thickness; so thick, in fact, they were, that some of the apartments were built in the body of the wall. There were various buildings within the inclosure. There was, in particular, one large, square tower, several stories in height, built of white stone. This tower, it is said, still stands in good preservation. There was a chapel, also, and various other buildings and apartments within the walls, for the use of the ducal family and their numerous retinue of servants and attendants, for the storage of munitions of war, and for the garrison. There were watch-towers on the corners of the walls, and on various lofty projecting pinnacles, where solitary sentinels watched, the livelong day and night, for any approaching danger. These sentinels looked down on a broad expanse of richly-cultivated country, fields beautified with groves of trees, and with the various colors presented by the changing vegetation, while meandering streams gleamed with their silvery radiance among them, and hamlets of laborers and peasantry were scattered here and there, giving life and animation to the scene.

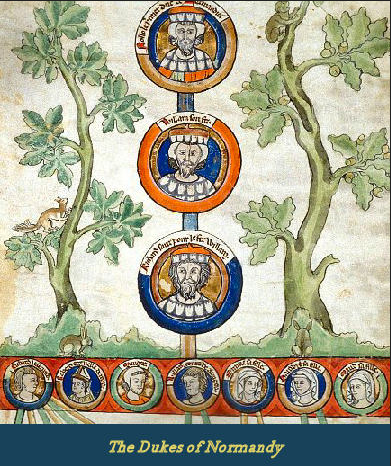

We have said that William’s father was Robert, the sixth Duke of Normandy, so that William himself, being his immediate successor, was the seventh in the line. And as it is the design of these narratives not merely to amuse the reader with what is entertaining as a tale, but to impart substantial historical knowledge, we must prepare the way for the account of William’s birth, by presenting a brief chronological view of the whole ducal line, extending from Rollo to William. We recommend to the reader to examine with special attention this brief account of William’s ancestry, for the true causes which led to William’s invasion of England can not be fully appreciated without thoroughly understanding certain important transactions in which some members of the family of his ancestors were concerned before he was born. This is particularly the case with the Lady Emma, who, as will be seen by the following summary, was the sister of the third duke in the line. The extraordinary and eventful history of her life is so intimately connected with the subsequent exploits of William, that it is necessary to relate it in full, and it becomes, accordingly, the subject of one of the subsequent chapters of this volume.

CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY OF THE NORMAN LINE

ROLLO, first Duke of Normandy

From A.D. 912 to A.D. 917

It was about 870 that Rollo was banished from Norway, and a few years after that, at most, that he landed in France. It was not, however, until 912 that he concluded his treaty of peace with Charles, so as to be fully invested with the title of Duke of Normandy.

He was advanced in age at this time, and, after spending five years in settling the affairs of his realm, he resigned his dukedom into the hands of his son, that he might spend the remainder of his days in rest and peace. He died in 922, five years after his resignation.

William I, second Duke of Normandy

From 917 to 942

William was Rollo’s son. He began to reign, of course, five years before his father’s death. He had a quiet and prosperous reign of about twenty-five years, but he was assassinated at last by a political enemy, in 942.

Richard I, third Duke of Normandy

From 942 to 996

He was only ten years old when his father was assassinated. He became involved in long and arduous wars with the King of France, which compelled him to call in the aid of more Northmen from the Baltic. His new allies, in the end, gave him as much trouble as the old enemy, with whom they came to help William contend; and he found it very hard to get them away. He wanted, at length, to make peace with the French king, and to have them leave his dominions; but they said, “That was not what they came for.” Richard had a beautiful daughter, named Emma, who afterward became a very important political personage, as will be seen more fully in a subsequent chapter.

Richard died in 996, after reigning fifty-four years.

Richard II, fourth Duke of Normandy

From 996 to 1026

Richard II was the son of Richard I, and as his father had been engaged during his reign in contentions with his sovereign lord, the King of France, he, in his turn, was harassed by long-continued struggles with his vassals, the barons and nobles of his own realm. He, too, sent for Northmen to come and assist him. During his reign there was a great contest in England between the Saxons and the Danes, and Ethelred, who was the Saxon claimant to the throne, came to Normandy, and soon afterward married the Lady Emma, Richard’s sister. The particulars of this event, from which the most momentous consequences were afterward seen to flow, will be given in full in a future chapter. Richard died in 1026. He left two sons, Richard and Robert. William the Conqueror was the son of the youngest, and was born two years before this Richard II died.

Richard III, fifth Duke of Normandy

From 1026 to 1028

He was the oldest brother, and, of course, succeeded to the dukedom. His brother Robert was then only a baron—his son William, afterward the Conqueror, being then about two years old. Robert was very ambitious and aspiring, and eager to get possession of the dukedom himself. He adopted every possible means to circumvent and supplant his brother, and, as is supposed, shortened his days by the anxiety and vexation which he caused him; for Richard died suddenly and mysteriously only two years after his accession. It was supposed by some, in fact, that he was poisoned, though there was never any satisfactory proof of this.

Robert, sixth Duke of Normandy

From 1028 to 1035

Robert, of course, succeeded his brother, and then, with the characteristic inconsistency of selfishness and ambition, he employed all the power of his realm in helping the King of France to subdue his younger brother, who was evincing the same spirit of seditiousness and insubmission that he had himself displayed. His assistance was of great importance to King Henry; it, in fact, decided the contest in his favor; and thus one younger brother was put down in the commencement of his career of turbulence and rebellion, by another who had successfully accomplished a precisely similar course of crime. King Henry was very grateful for the service thus rendered, and was ready to do all in his power, at all times, to co-operate with Robert in the plans which the latter might form. Robert died in 1035, when William was about eleven years old.

And here we close this brief summary of the history of the ducal line, as we have already passed the period of William’s birth; and we return, accordingly, to give in detail some of the particulars of that event.

Although the dukes of Normandy were very powerful potentates, reigning, as they did, almost in the character of independent sovereigns, over one of the richest and most populous territories of the globe, and though William the Conqueror was the son of one of them, his birth was nevertheless very ignoble. His mother was not the wife of Robert his father, but a poor peasant girl, the daughter of an humble tanner of Falaise; and, indeed, William’s father, Robert, was not himself the duke at this time, but a simple baron, as his father was still living. It was not even certain that he ever would be the duke, as his older brother, who, of course, would come before him, was also then alive. Still, as the son and prospective heir of the reigning duke, his rank was very high.

The circumstances of Robert’s first acquaintance with the tanner’s daughter were these. He was one day returning home to the castle from some expedition on which he had been sent by his father, when he saw a group of peasant girls standing on the margin of the brook, washing clothes. They were barefooted, and their dress was in other respects disarranged. There was one named Arlotte, the daughter of a tanner of the town, whose countenance and figure seem to have captivated the young baron. He gazed at her with admiration and pleasure as he rode along. Her complexion was fair, her eyes full and blue, and the expression of her countenance was frank, and open, and happy. She was talking joyously and merrily with her companions as Robert passed, little dreaming of the conspicuous place on the page of English history which she was to occupy, in all future time, in connection with the gay horseman who was riding by.

The etiquette of royal and ducal palaces and castles in those days, as now, forbade that a noble of such lofty rank should marry a peasant girl. Robert could not, therefore, have Arlotte for his wife; but there was nothing to prevent his proposing her coming to the castle and living with him—that is, nothing but the law of God, and this was an authority to which dukes and barons in the Middle Ages were accustomed to pay very little regard. There was not even a public sentiment to forbid this, for a nobility like that of England and France in the Middle Ages stands so far above all the mass of society as to be scarcely amenable at all to the ordinary restrictions and obligations of social life. And even to the present day, in those countries where dukes exist, public sentiment seems to tolerate pretty generally whatever dukes see fit to do.

Accordingly, as soon as Robert had arrived at the castle, he sent a messenger from his retinue of attendants down to the village, to the father of Arlotte, proposing that she should come to the castle. The father seems to have had some hesitation in respect to his duty. It is said that he had a brother who was a monk, or rather hermit, who lived a life of reading, meditation, and prayer, in a solitary place not far from Falaise. Arlotte’s father sent immediately to this religious recluse for his spiritual counsel. The monk replied that it was right to comply with the wishes of so great a man, whatever they might be. The tanner, thus relieved of all conscientious scruples on the subject by this high religious authority, and rejoicing in the opening tide of prosperity and distinction which he foresaw for his family through the baron’s love, robed and decorated his daughter, like a lamb for the sacrifice, and sent her to the castle.

Arlotte had one of the rooms assigned her, which was built in the thickness of the wall. It communicated by a door with the other apartments and inclosures within the area, and there were narrow windows in the masonry without, through which she could look out over the broad expanse of beautiful fields and meadows which were smiling below. Robert seems to have loved her with sincere and strong affection, and to have done all in his power to make her happy. Her room, however, could not have been very sumptuously furnished, although she was the favorite in a ducal castle—at least so far as we can judge from the few glimpses we get of the interior through the ancient chroniclers’ stories. One story is, that when William was born, his first exploit was to grasp a handful of straw, and to hold it so tenaciously in his little fist that the nurse could scarcely take it away. The nurse was greatly delighted with this infantile prowess; she considered it an omen, and predicted that the babe would some day signalize himself by seizing and holding great possessions. The prediction would have been forgotten if William had not become the conqueror of England at a future day. As it was, it was remembered and recorded; and it suggests to our imagination a very different picture of the conveniences and comforts of Arlotte’s chamber from those presented to the eye in ducal palaces now, where carpets of velvet silence the tread on marble floors, and favorites repose under silken canopies on beds of down.

The babe was named William, and he was a great favorite with his father. He was brought up at Falaise. Two years after his birth, Robert’s father died, and his oldest brother, Richard III., succeeded to the ducal throne. In two years more, which years were spent in contention between the brothers, Richard also died, and then Robert himself came into possession of the castle in his own name, reigning there over all the cities and domains of Normandy.

William was, of course, now about four years old. He was a bright and beautiful boy, and he grew more and more engaging every year. His father, instead of neglecting and disowning him, as it might have been supposed he would do, took a great deal of pride and pleasure in witnessing the gradual development of his powers and his increasing attractiveness, and he openly acknowledged him as his son.

In fact, William was a universal favorite about the castle. When he was five and six years old he was very fond of playing the soldier. He would marshal the other boys of the castle, his playmates, into a little troop, and train them around the castle inclosures, just as ardent and aspiring boys do with their comrades now. He possessed a certain vivacity and spirit too, which gave him, even then, a great ascendency over his playfellows. He invented their plays; he led them in their mischief; he settled their disputes. In a word, he possessed a temperament and character which enabled him very easily and strongly to hold the position which his rank as son of the lord of the castle so naturally assigned him.

A few years thus passed away, when, at length, Robert conceived the design of making a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. This was a plan, not of humble-minded piety, but of ambition for fame. To make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land was a romantic achievement that covered whoever accomplished it with a sort of sombre glory, which, in the case of a prince or potentate, mingled with, and hallowed and exalted, his military renown. Robert determined on making the pilgrimage. It was a distant and dangerous journey. In fact, the difficulties and dangers of the way were perhaps what chiefly imparted to the enterprise its romance, and gave it its charms. It was customary for kings and rulers, before setting out, to arrange all the affairs of their kingdoms, to provide a regency to govern during their absence, and to determine upon their successors, so as to provide for the very probable contingency of their not living to return.

As soon, therefore, as Robert announced his plan of a pilgrimage, men’s minds were immediately turned to the question of the succession. Robert had never been married, and he had consequently no son who was entitled to succeed him. He had two brothers, and also a cousin, and some other relatives, who had claims to the succession. These all began to maneuver among the chieftains and nobles, each endeavoring to prepare the way for having his own claims advanced, while Robert himself was secretly determining that the little William should be his heir. He said nothing about this, however, but he took care to magnify the importance of his little son in every way, and to bring him as much as possible into public notice. William, on his part, possessed so much personal beauty, and so many juvenile accomplishments, that he became a great favorite with all the nobles, and chieftains, and knights who saw him, sometimes at his father’s castle, and sometimes away from home, in their own fortresses or towns, where his father took him, from time to time, in his train.

At length, when affairs were ripe for their consummation, Duke Robert called together a grand council of all the subordinate dukes, and earls, and barons of his realm, to make known to them the plan of his pilgrimage. They came together from all parts of Normandy, each in a splendid cavalcade, and attended by an armed retinue of retainers. When the assembly had been convened, and the preliminary forms and ceremonies had been disposed of, Robert announced his grand design.

As soon as he had concluded, one of the nobles, whose name and title was Guy, count of Burgundy, rose and addressed the duke in reply. He was sorry, he said, to hear that the duke, his cousin, entertained such a plan. He feared for the safety of the realm when the chief ruler should be gone. All the estates of the realm, he said, the barons, the knights, the chieftains and soldiers of every degree, would be all without a head.

“Not so,” said Robert: “I will leave you a master in my place.” Then, pointing to the beautiful boy by his side, he added, “I have a little fellow here, who, though he is little now, I acknowledge, will grow bigger by and by, with God’s grace, and I have great hopes that he will become a brave and gallant man. I present him to you, and from this time forth I give him seizin of the Duchy of Normandy as my known and acknowledged heir. And I appoint Alan, duke of Brittany, governor of Normandy in my name until I shall return, and in case I shall not return, in the name of William my son, until he shall become of manly age.”

The assembly was taken wholly by surprise at this announcement. Alan, duke of Brittany, who was one of the chief claimants to the succession, was pleased with the honor conferred upon him in making him at once the governor of the realm, and was inclined to prefer the present certainty of governing at once in the name of others, to the remote contingency of reigning in his own. The other claimants to the inheritance were confounded by the suddenness of the emergency, and knew not what to say or do. The rest of the assembly were pleased with the romance of having the beautiful boy for their feudal sovereign. The duke saw at once that every thing was favorable to the accomplishment of his design. He took the lad in his arms, kissed him, and held him out in view of the assembly. William gazed around upon the panoplied warriors before him with a bright and beaming eye. They knelt down as by a common accord to do him homage, and then took the oath of perpetual allegiance and fidelity to his cause.

Robert thought, however, that it would not be quite prudent to leave his son himself in the custody of these his rivals, so he took him with him to Paris when he set out upon his pilgrimage, with a view of establishing him there, in the court of Henry, the French king, while he should himself be gone. Young William was presented to the French king, on a day set apart for the ceremony, with great pomp and parade. The king held a special court to receive him. He seated himself on his throne in a grand apartment of his palace, and was surrounded by his nobles and officers of state, all magnificently dressed for the occasion. At the proper time, Duke Robert came in, dressed in his pilgrim’s garb, and leading young William by the hand. His attendant pilgrim knights accompanied him. Robert led the boy to the feet of their common sovereign, and, kneeling there, ordered William to kneel too, to do homage to the king. King Henry received him very graciously. He embraced him, and promised to receive him into his court, and to take the best possible care of him while his father was away. The courtiers were very much struck with the beauty and noble bearing of the boy. His countenance beamed with an animated, but yet very serious expression, as he was somewhat awed by the splendor of the scene around him. He was himself then nine years old.

[…] Source link […]