Editor’s note: Here follow Chapters 7 through 12 of My Reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, by General Ben Viljoen (published 1902). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER VII

THE BOER GENERAL’S SUPERSTITIONS.

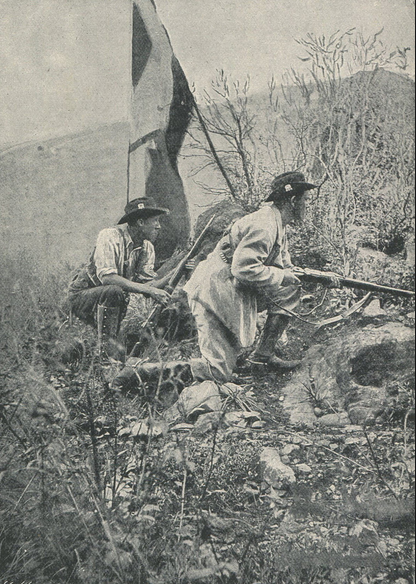

A few days after we had arrived before Ladysmith we joined an expedition to reconnoitre the British entrenchments, and my commando was ordered near some forts on the north-westerly side of the town. Both small and large artillery were being fired from each side. We approached within 800 paces of a fort; it was broad daylight and the enemy could therefore see us distinctly, knew the exact range, and received us with a perfect hailstorm of fire. Our only chance was to seek cover behind kopjes and in ditches, for on any Boer showing his head the bullets whistled round his ears. Here two of my burghers were severely wounded, and we had some considerable trouble to get them through the firing line to our ambulance. At last, late in the afternoon, came the order to retire, and we retired after having achieved nothing.

I fail to this day to see the use of this reconnoitring, but at Ladysmith everything was equally mysterious and perplexing. It was perhaps that my knowledge of military matters was too limited to understand the subtle manœuvres of those days. But I have made up my mind not to criticise our leader’s military strategy, though I must say at this juncture that the whole siege of Ladysmith and the manner in which the besieged garrison was ineffectually pounded at with our big guns for several months, seem to me an unfathomable mystery, which, owing to Joubert’s untimely death, will never be explained satisfactorily. But I venture to describe Joubert’s policy outside Ladysmith as stupid and primitive, and in another chapter I shall again refer to it.

After another fortnight or so, we were ordered away to guard another position to the south-west of Ladysmith, as the Free State commando under Commandant Nel, and, unless I am mistaken, under Field-Cornet Christian de Wet (afterwards the world-famous chief Commander of the Orange Free State, and of whom all Afrikanders are justly proud), had to go to Cape Colony.

Here I was under the command of Dijl Erasmus, who was then General and a favourite of General Joubert. We had plenty of work given us. Trenches had to be dug and forts had to be constructed and remodelled. At this time an expedition ventured to Estcourt, under General Louis Botha, who replaced General L. Meyer, sent home on sick leave. My commando joined the expedition under Field-Cornet J. Kock, who afterwards caused me a lot of trouble.

I can say but little of this expedition to Estcourt, save that the Commander-in-Chief accompanied it. But for his being with us, I am convinced that General Botha would have pushed on at least as far as Pietermaritzburg, for the English were at that time quite unable to stop our progress. But after we got to Estcourt, practically unopposed, Joubert, though our burghers had been victorious in battle after battle, ordered us to retreat. The only explanation General Joubert ever vouchsafed about the recall of this expedition was that in a heavy thunderstorm which had been raging for two nights near Estcourt, two Boers had been struck by lightning, which, according to his doctrine, was an infallible sign from the Almighty that the commandos were to proceed no further. It seems incredible that in these enlightened days we should find such a man in command of an army; it is, nevertheless, a fact that the loss of two burghers induced our Commandant-General to recall victorious commandos who were carrying all before them. The English at Pietermaritzburg, and even at Durban, were trembling lest we should push forward to the coast, knowing full well that in no wise could they have arrested our progress. And what an improvement in our position this would have meant! As it was, our retirement encouraged the British to push forward their fighting line so far as Chieveley Station, near the Tugela river, and the commandos had to take up a position in the “randjes,” on the westerly banks of the Tugela.

CHAPTER VIII

THE “GREAT POWERS” TO INTERVENE.

During the retreat of our army to the frontier of the Transvaal Republic nothing of importance occurred. Here again confusion reigned supreme, and none of the commandos were over-anxious to form rearguards. Our Hollander Railway Company made a point of placing a respectful distance between her rolling-stock and the enemy, and, anxious to lose as few carriages as possible, raised innumerable difficulties when asked to transport our men, provisions and ammunition. Our generals had meantime proceeded to Laing’s Nek by rail to seek new positions, and there was no one to maintain order and discipline.

About 150 Natal Afrikanders who had joined our commandos when these under the late General Joubert occupied the districts about Newcastle and Ladysmith, now found themselves in an awkward position. They elected to come with us, accompanied by their families and live stock, and they offered a most heartrending spectacle. Long rows of carts and wagons wended their way wearily along the road to Laing’s Nek. Women in tears, with their children and infants in arms, cast reproachful glances at us as being the cause of their misery. Others occupied themselves more usefully in driving their cattle. Altogether it was a scene the like of which I hope never to see again.

The Natal kaffirs now had an opportunity of displaying their hatred towards the Boers. As soon as we had left a farm and its male inhabitants had gone, they swooped down on the place and wrought havoc and ruin, plundering and looting to their utmost carrying capacity. Some even assaulted women and children, and the most awful atrocities were committed. I attach more blame to the whites who encouraged these plundering bands, especially some of the Imperial troops and Natal men in military service. Not understanding the bestial nature of the kaffirs, they used them to help carry out their work of destruction, and although they gave them no actual orders to molest the people, they took no proper steps of preventing this.

When our commando passed through Newcastle, we found the place almost entirely deserted, excepting for a few British subjects who had taken an oath of neutrality to the Boers.

I regret to have to state that during our retreat a number of irresponsible persons set fire to the Government buildings in that town. It is said that an Italian officer burned a public hall on no reasonable pretext; certainly he never received orders to that effect. As may be expected of an invading army, some of our burgher patrols and other isolated bodies of troops looted and destroyed a number of houses which had been temporarily deserted. But with the exception of these few cases, I can state that no outrages were committed by us in Natal, and no property was needlessly destroyed.

On our arrival at Laing’s Nek a Council of War was immediately held to decide our future plans.

We now found ourselves once more on the old battlefields of 1880 and 1881, where Boer and Briton had met 20 years before to decide by trial of arms who should be master of the S. A. Republic. Traces of that desperate struggle were still plainly visible, and the historic height of Majuba stood there, an isolated sentinel, recalling to us the battle in which the unfortunate Colley lost both the day and his life.

I was told off to take up a position in the Nek where the wagon-road runs to the east across the railway-tunnel, and here we made preparations for digging trenches and placing our guns. Soon after we had completed our entrenchments we once more saw the enemy. They were lying at Schuinshoogte on the Ingogo, and had sent a mounted corps with two guns to the Nek. Although we had no idea of the enemy’s strength, we were fully prepared to meet the attack; the Pretoria, Lydenburg and other laagers were posted to the left on the summit of Majuba Hill, and other commandos held good positions on the east. But the enemy evidently thought that we had fled all the way back to Pretoria, and not expecting to find the Nek occupied, advanced quite unconcerned. We fired a few volleys at them, which caused them to halt in considerable surprise, and, replying with a little artillery fire, they quickly returned to Schuinshoogte. We had, however, to be on our guard both day and night. It was bitterly cold at the time and a strong easterly wind was blowing.

Next day something occurred which afforded a change to the monotony of our situation, namely, the arrival from Pretoria of Mr. John Lombaard, member of the First Volksraad for Bethel. He asked permission to address us and informed us that we need only hold out another fortnight, for news from Europe had reached them to the effect that the Great Powers had decided to put an end to the War. This communication emanating from such a semi-official source was believed by a certain number of our men, but I think it did very little to brighten up the spirits of the majority, or arouse them from the lethargy into which they seemed to have fallen. A fortnight passed, and a month, without us hearing anything further of this expected intervention, and I have never been able to discover on whose authority and by whose orders Mr. Lombaard made to us that remarkable communication.

Meantime, General Buller did not seem at all anxious to attack us, perhaps fearing a repetition of the “accidents” on the Tugela; or possibly he thought that our position was too strong. For some reason, therefore, Laing’s Nek was never attacked, and Buller afterwards, having made a huge “detour,” broke through Botha’s Pass. Meanwhile, Lord Roberts and his forces were marching without opposition through the Orange Free State, and I was ordered to proceed to Vereeniging with my commando. We left Laing’s Nek on the 19th of May, and proceeded to the Free State frontier by rail.

CHAPTER IX

COLENSO AND SPION KOP FIGHTS.

Eight days after my commando had been stationed in my new position under General Erasmus, I received instructions to march to Potgietersdrift, on the Upper Tugela, near Spion Kop, and there to put myself at Andries Cronje’s disposal. This gentleman was then a general in the Orange Free State Army, and although a very venerable looking person, was not very successful as a commander. Up to the 14th of December, 1899, no noteworthy incident took place, and nothing was done but a little desultory scouting along the Tugela, and the digging of trenches.

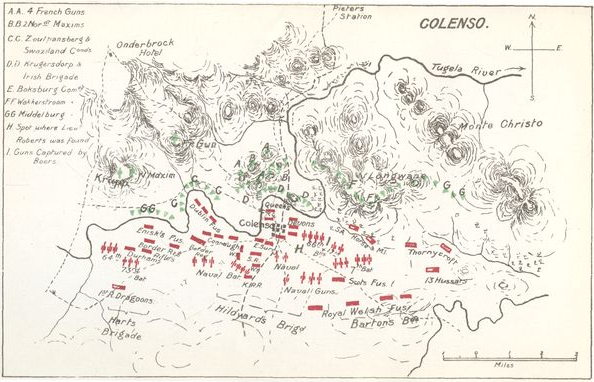

At last came the welcome order summoning us to action; and we were bidden to march on Colenso Heights with 200 men to fill up the ranks, as a fight was imminent. We left under General Cronje and arrived the next morning at daybreak, and a few hours after began the battle now known to the world as the Battle of Colenso (15th December, 1899).

I afterwards heard that the commandos under General Cronje were to cross the river and attack the enemy’s left flank. This did not happen, as the greatest confusion prevailed owing to the various contradictory orders given by the generals. For instance, I myself received four contradictory orders from four generals within the space of ten minutes. I, however, took the initiative in moving my men up to the river to attempt the capture of a battery of guns on the enemy’s left flank which had been left unprotected, as was the case with the ten guns which fell into our hands later in the day. I had approached within 1,400 paces of the enemy, and my burghers were following close behind me when an adjutant from General Botha (accompanied by a gentleman named C. Fourie, who was then also parading as a general) galloped up to us and ordered us at once to join the Ermelo commando, which was said to be too weak to resist the attacks of the enemy. We hurried thither as quickly as we could round the rear of the fighting line, where we were obliged to off-saddle and walk up to the position of the Ermelo burghers. This was no easy task; the battle was now in full swing, and the enemy’s shells were bursting in dozens around us, and in the burning sun we had to run some miles.

When we arrived at our destination Mr. Fourie (the pseudo general) and his adjutant could nowhere be found. As to the Ermelo burghers, they said they were quite comfortable, and had asked for no assistance.

Not a single shell had reached them, for a clump of aloe trees stood a hundred yards away, which the English presumably had taken for Boers, judging by the terrific bombardment these trees were being subjected to.

By this time the attack was repulsed, and General Buller was in full retreat to Chieveley, though our commando had been unable to take an active part in the fighting, at which we were greatly disappointed. It is much to be regretted that the retreat of the enemy was not followed up at once. Had this been done, the campaign in Natal would have taken an entirely different aspect, and very probably would have been attended by a more favourable conclusion. I consider myself far from a prophet, but this I know; and if we had then and on subsequent occasions followed up our successes, the result of the Campaign would have been far more satisfactory to us.

After I had assisted in bringing away through the river the guns we had taken, and seen to other matters which required my immediate attention, I was ordered to remain with the Ermelo commando at Colenso, near Toomdrift, and to await there further instructions.

A few weeks of inactivity followed, the English sending us each day a few samples of their shells from their 4·7 Naval guns. Unfortunately, our guns were of much smaller calibre, and we could send them no suitable reply. As a rule we would lie in the trenches, and a burgher would be on the look-out. So soon as he saw the flash of an English gun, he would cry out; “There’s a shell,” and we then sought cover, so that the enemy seldom succeeded in harming us.

One day one of these big shells fell amongst a group of fourteen burghers who were at dinner. The shell struck a sharp rock, which it splintered into fragments, and was emitting its yellow lyddite; but, fortunately, the fuse refused to burn, and the shell did not explode, so we had a narrow escape that day from a small catastrophe.

My laager had been at Potgietersdrift all this time, and for the time being we were deprived of our tents. We were not sorry, therefore, when we were ordered to leave Colenso and to return to our camp.

A few days after we were told off to take up a position at the junction of the Little and the Big Tugela, between Spion Kop and Colenso. Here we celebrated our first Christmas in the field; our friends at Johannesburg had sent us a quantity of presents by means of a friend, Attorney Raaff, comprising cakes, cigars, cigarettes, tobacco and other luxuries. Along this part of the Tugela we found a fair quantity of vegetables, and poultry, and as their respective owners had fled we were unable to pay for what we had. We were obliged, therefore, to “borrow” all these things for the banquet befitting to the occasion.

But General Buller had not quite finished with us yet. He marched on Spion Kop, but with the exception of a feint attack nothing of importance happened then. One day I went across the river with a patrol to discover what the enemy was doing, when we suddenly came across nine English spies, who fled as soon as they saw us. We galloped after them, trying to cut them off from the main body, which was at a little distance away from us, and would no doubt have overtaken them, but, riding at a breakneck speed over a mountain ridge, we found ourselves suddenly confronted with a strong English mounted corps, apparently engaged in drilling. We were only 500 paces away from them, and we jumped off our horses, and opened fire. But there were only a dozen of us, and the enemy soon began sending us a few shells, and prepared to attack us with their whole force. About a hundred mounted men, with horses in the best of condition, set off to pursue us.

We were obliged to ride back by the same path we had come by, which was fortunate for us, as we knew the way and could ride through crevices and dongas without any hesitation. In this way we soon gave our pursuers the slip.

Buller’s forces seemed at first to have the intention of forcing their way through near Potgietersdrift, and they took possession of all the “randts” on their side of the river, causing us to strengthen the position on our side. We thus had to shift our commando again to Potgietersdrift, where we soon had the enemy’s Naval guns playing on our positions. This continued day and night for a whole week.

It seemed as if General Buller were determined to annihilate all the Boers with his lyddite shells, so as to enable the soldiers to walk at their leisure to the release of Ladysmith. Certainly we suffered considerably from lyddite fumes.

The British next made a feint attack near Potgietersdrift, advancing with a great clamour till they had come within 2,000 paces of us, where they occupied various “randts” and kopjes, always under cover of their artillery. Once they came a little too close to our positions, and we suddenly opened fire on them. The result was that their ambulance waggons were seen to become very busy driving backwards and forwards.

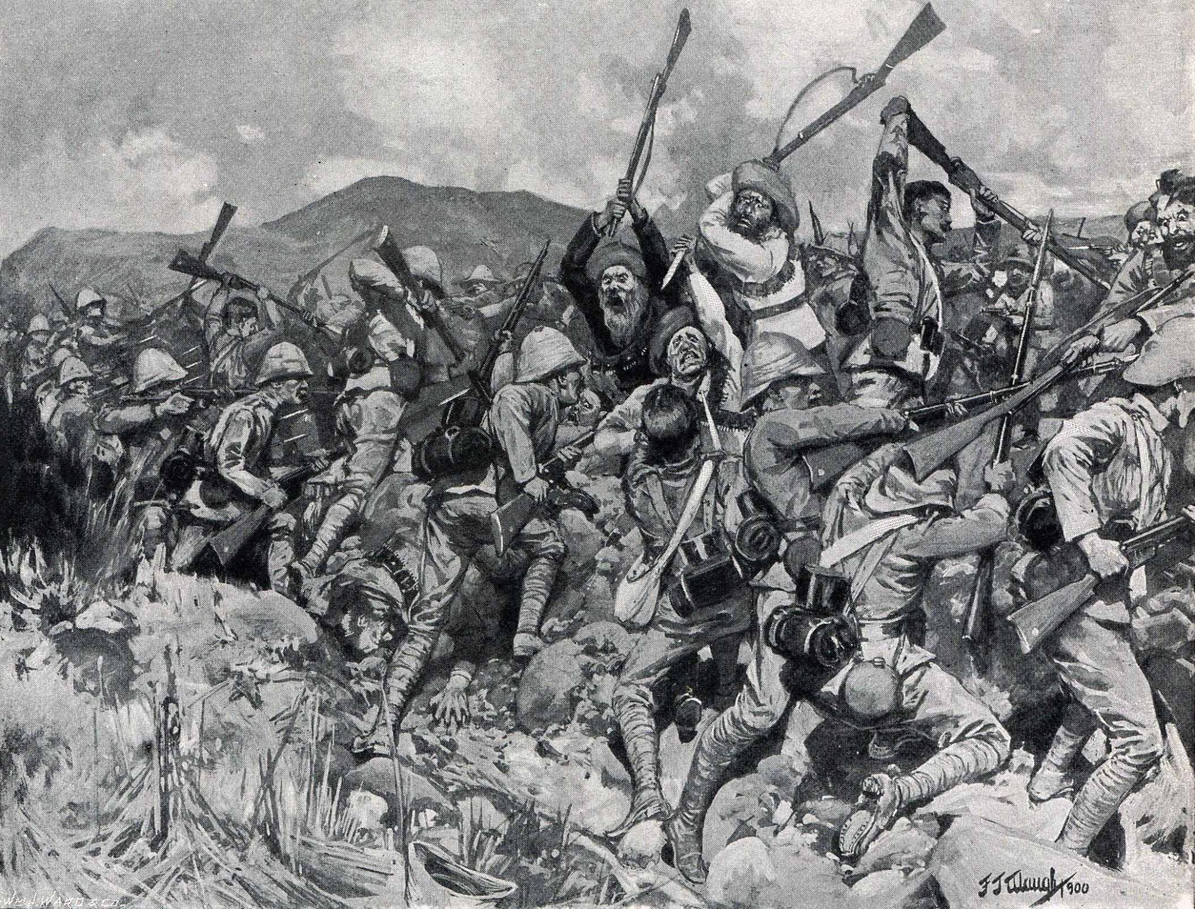

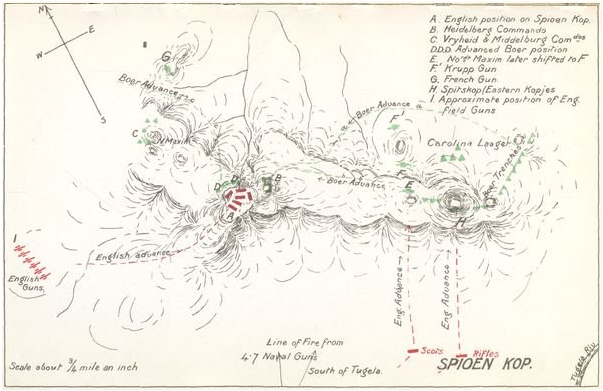

This “feint,” however, was only made in order to divert our attention, while Buller was concentrating his troops and guns on Spion Kop. The ruse succeeded to a large extent, and on the 21st January the memorable battle of Spion Kop (near the Upper Tugela) began.

General Warren, who, I believe, was in command here, had ordered another “feint” attack from the extreme right wing. General Cronje and the Free Staters had taken up a position at Spion Kop, assisted by the commandos of General Erasmus and Schalk Burger.

The fight lasted the whole of that day and the next, and became more and more fierce. Luckily General Botha appeared on the scene in time, and re-arranged matters so well and with so much energy that the enemy found itself well employed, and was kept in check at all points.

I had been ordered to defend the position at Potgietersdrift, but the fighting round Spion Kop became so serious that I was obliged to send up a field cornet with his men as a reinforcement, which was soon followed by a second contingent, making altogether 200 Johannesburgers in the fight, of whom nine were killed and 18 wounded. The enemy had reached the top of the “kop” on the evening of the second day of the fight, not, however, without having sustained considerable losses. At this juncture one of our generals felt so disheartened that he sent away his carts, and himself left the battlefield.

But General Botha kept his ground like a man, surrounded by the faithful little band who had already borne the brunt of this important battle. And one can imagine our delight when next morning we found that the English had retreated, leaving that immense battlefield, strewn with hundreds of dead and wounded, in our hands.

“What made them leave so suddenly last night,” was the question we asked each other then, and which remains unanswered to this day.

General Warren has stated that the cause of his departure was the want of water, but I can hardly credit that statement, as water could be obtained all the way to the top of Spion Kop; and even had it been wanting it is not likely that after a sacrifice of 1,200 to 1,300 lives the position would have been abandoned on this account alone. Our victory was undoubtedly a fluke.

CHAPTER X

THE BATTLE OF VAALKRANTZ.

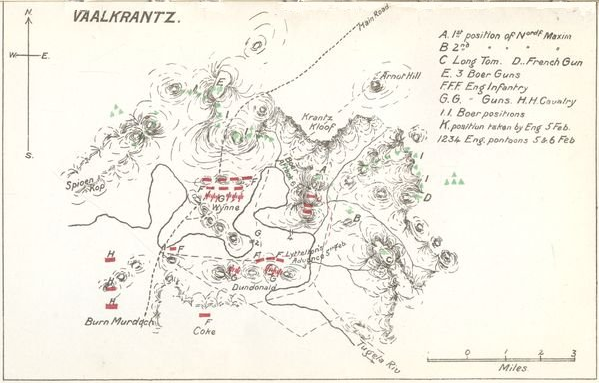

Soon after his defeat at Spion Kop, General Buller, moved by the earnest entreaties for help from Ladysmith, and pressed by Lord Roberts, attempted a third time to break through our lines. This time my position had to bear the onslaught of his whole forces. For some days it had been clear to me what the enemy intended to do, but I wired in vain to the Commander-in-Chief to send me reinforcements, and I was left to defend a front, one and a half miles in length, with about 400 men. After many requests I at last moved General Joubert to send me one of the guns known as “Long Toms,” which was placed at the rear of our position, and enabled us to command the Vaalkrantz, or, as we called it, “Pontdrift” kopjes. But instead of the required reinforcements, the Commander sent a telegram to General Meyer to Colenso, telling him to come and speak to me, and to put some heart into me, for it seemed, he said, “as if I had lost faith.”

General Meyer came, and I explained to him how matters stood, and that I should not be able to check the enormous attacking force with my commando alone. The British were at this time only 7,000 paces away from us. The required assistance, however, never came, although I told the General that a faith strong enough to move Majuba Hill would be of no avail without a sufficient number of men.

Early in the morning of the 5th February, 1900, my position was heavily bombarded, and before the sun had risen four of my burghers had been put hors de combat. The enemy had placed their naval guns on the outskirts of the wood known as “Zwartkop” so as to be able to command our position from an elevation of about 400 feet. I happened to be on the right flank with ninety-five burghers and a pom-pom; my assistant, Commandant Jaapie du Preez, commanding the left flank.

The assailants threw two pontoon bridges across the river and troops kept pouring over from 10 o’clock in the morning. The whole of the guns’ fire was now concentrated on my position; and although we answered with a well-directed fire, they charged time after time.

The number of my fighting men was rapidly diminishing. I may say this was the heaviest bombardment I witnessed during the whole of the campaign. It seemed to me as if all the guns of the British army were being fired at us.

Their big lyddite guns sent over huge shells, which mowed down all the trees on the kopje, while about fifty field pieces were incessantly barking away from a shorter range. Conan Doyle, in his book, “The Great Boer War,” states that the British had concentrated no less than seventy-three guns on that kopje. In vain I implored the nearest Generals for reinforcements and requested our artillery in Heaven’s name to aim at the enemy’s guns. At last, however, “Long Tom” commenced operations, but the artillerymen in charge had omitted to put the powder in a safe place and it was soon struck by a lyddite shell which set the whole of it on fire. This compelled us to send to the head laager near Ladysmith for a fresh supply of powder.

On looking about me to see how my burghers were getting on I found that many around me had been killed and others were wounded. The clothes of the latter were burnt and they cried out for help in great agony.

Our pom-pom had long since been silenced by the enemy, and thirty of my burghers had been put out of the fight. The enemy’s infantry was advancing nearer and nearer and there was not much time left to think. I knelt down behind a kopje, along with some of the men, and we kept firing away at 400 paces, but although we sent a good many to eternal rest, the fire of the few burghers who were left was too weak to stem the onslaught of those overwhelming numbers.

A lyddite shell suddenly burst over our very heads. Four burghers with me were blown to pieces and my rifle was smashed. It seemed to me as if a huge cauldron of boiling fat had burst over us and for some minutes I must have lost consciousness. A mouthful of brandy and water (which I always carried with me) was given me and restored me somewhat, and when I opened my eyes I saw the enemy climbing the kopje on three sides of us, some of them only a hundred paces away from me.

I ordered my men to fall back and took charge of the pom-pom, and we then retired under a heavy rifle and gun fire. Some English writers have made much ado about the way in which our pom-pom was saved, but it was nothing out of the ordinary. Of the 95 burghers with me 29 had been killed, 24 wounded.

When I had a few minutes rest I felt a piercing pain in my head, and the blood began to pour from my nose and ears.

We had taken up another position at 1,700 paces, and fired our pom-pom at the enemy, who now occupied our position of a few minutes before. Our other guns were being fired as well, which gave the British an exciting quarter of an hour. On the right and left of the positions taken by them our burghers were still in possession of the “randten”; to the right Jaapie du Preez, with the loss of only four wounded, kept his ground with the rest of my commando.

The next morning the fight was renewed, and our “Long Tom” now took the lead in the cannon-concert, and seemed to make himself very unpleasant to the enemy.

The whole day was mainly a battle of big guns. My headache grew unbearable, and I was very feverish. General Botha had meanwhile arrived with reinforcements, and towards evening things took a better turn.

But I was temporarily done for, and again lost consciousness, and was taken to the ambulance. Dr. Shaw did his best, I hear, for me; but I was unconscious for several days, and when I revived the doctor told me I had a slight fracture of the skull caused by the bursting of a shell. The injuries, however, could not have been very serious for ten days after I was able to leave my bed. I then heard that the night I had been taken to the hospital, the British had once more been forced to retire across the Tugela, and early in the morning of the 7th of February our burghers were again in possession of the kopje “Vaalkrantz,” round which such a fierce fight had waged and for the possession of which so much blood had been spilled.

So far as I could gather from the English official reports they lost about 400 men, while our dead and wounded numbered only sixty-two.

Taking into consideration the determination with which General Buller had attacked us, and how dearly he had paid for this third abortive attempt, the retreat of his troops remains as much of a mystery to me as that at Spion Kop.

Our “Long Tom” was a decided success, and had proved itself to be exceedingly useful.

The Battle of “Vaalkrantz” kopje was to me and to the Johannesburg commando undoubtedly the most important and the fiercest fight in this war, and although one point in our positions was taken, I think that on the whole I may be proud of our defence. About two-thirds of its defenders were killed or wounded before the enemy took that spot, and all who afterwards visited the kopje where our struggle had taken place had to admit that unmistakable evidence showed it to be one of the hottest fights of the Natal campaign. All the trees were torn up or smashed by shells, great blocks of rock had been splintered and were stained yellow by the lyddite; mutilated bodies were lying everywhere—Briton and Boer side by side; for during the short time “Vaalkrantz” had been in their possession the English had not had an opportunity of burying the bodies of friends or foe.

I think I may quote a few paragraphs of what Dr. Doyle says in his book about this engagement:—

“The artillery-fire (the “Zwartkop” guns and other batteries) was then hurriedly aimed at the isolated “Vaalkrantz” (the real object of the attack), and had a terrific effect. It is doubtful whether ever before a position has been exposed to such an awful bombardment. The weight of the ammunition fired by some of the cannon was greater than that of an entire German battery during the Franco-Prussian war.”

Prince Kraft describes the 4 and 6-pounders as mere toys compared with machine Howitzer and 4.7 guns.

Dr. Doyle, however, is not sure about the effect of these powerful guns, for he says:—

“Although the rims of the kopje were being pounded by lyddite and other bombs it is doubtful whether this terrific fire did much damage among the enemy, as seven English officers and 70 men were lying dead on the kopje against only a few Boers, who were found to have been wounded.”

Of the pom-pom, which I succeeded in saving from the enemy’s hands, the same writer says:—

“It was during this attack that something happened of a more picturesque and romantic nature than is usually the case in modern warfare; here it was not a question of combatants and guns being invisible or the destruction of a great mass of people. In this case it concerns a Boer gun, cut off by the British troops, which all of a sudden came out of its hiding-place and scampered away like a frightened hare from his lair. It fled from the danger as fast as the mules’ legs would take it, nearly overturning, and jolting and knocking against the rocks, while the driver bent forward as far as he could to protect himself from the shower of bullets which were whistling round his ears in all directions. British shells to the right of him, shells to the left of him bursting and spluttering, lyddite shrapnel fuming and fizzing and making the splinters fly. But over the “randtje” the gun disappeared, and in a few minutes after it was in position again, and dealing death and destruction amongst the British assailants.”

While I was under treatment in Dr. Shaw’s ambulance I was honoured by a visit from General Joubert, who came to compliment me on what he called the splendid defence of Vaalkrantz, and to express his regret at the heavy loss sustained by our commando. I heard from Dr. Shaw that after the battle the groans and cries of the wounded burghers could be heard in the immediate neighbourhood of the English outposts. Some burghers volunteered to go, under cover of the darkness, to see if they could save these wounded men. They cautiously crept up to the foot of the kopjes, from where they could plainly see the English sentinels, and a little further down found in a ditch two of our wounded, named Brand and Liebenberg; the first had an arm and a leg smashed, the latter had a bullet in his thigh.

One can imagine what a terrible plight they were in after laying there for two nights and a day, exposed to the night’s severe cold and the day’s scorching sun. Their wounds were already decomposing, and the odour was most objectionable.

The two unfortunate men were at once carried to the laager and attended to with greatest care. Poor Liebenberg died of his wounds soon after. Brand, the youngest son of the late President Brand, of the Orange Free State, soon recovered, if I remember rightly.

At the risk of incurring the displeasure of a great number of people by adding the following statement to my description of the battle of Vaalkrantz, I feel bound to state that Commandant-General Joubert, after our successes at Colenso, Spion Kop, and Vaalkrantz, asked the two State Presidents, Kruger and Steyn, to consider the urgency of making peace overtures to the English Government. He pointed out that the Republics had no doubt reached the summit of their glory in the War. The proposal read as follows: That the Republican troops should at once evacuate British territory, compensation to be given for the damage to property, etc., inflicted by our commandos, against which the British Government was to guarantee that the Republics should be spared from any further incursions or attacks from British troops, and to waive its claim of Suzerainty; and that the British Government should undertake not to interfere with the internal affairs and legal procedure of the two Republics, and grant general amnesty to the colonial rebels.

Commander-in-Chief Joubert defended these proposals by pointing out that England was at that moment in difficulties, and had suffered repeated serious defeats. The opportunity should be taken, urged the General.

He was supported by several officers, but other Boer leaders contended that Natal, originally Boer territory, should never again be ceded to the enemy. As we heard nothing more of these proposals, I suppose the two State Presidents rejected them.

CHAPTER XI

THE TURN OF THE TIDE.

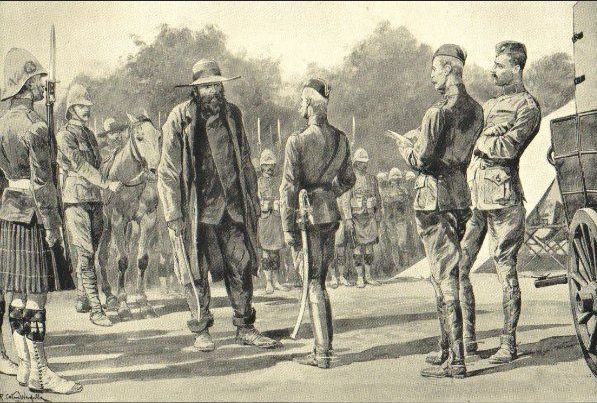

After the English forces had retreated from Vaalkrantz across the Tugela, a patrol of my commando under my faithful adjutant, J. Du Preez, who had taken my place for the time being, succeeded in surprising a troop of fifty Lancers, of the 17th regiment, I believe, near Zwartkop, east of the Tugela, and making them prisoners after a short skirmish. Among these men, who were afterwards sent to Pretoria, was a certain Lieutenant Thurlington. It was a strange sight to see our patrol coming back with their victims, each Boer brandishing a captured lance.

Being still in the hospital in feeble health without any prospect of a speedy recovery, I took the doctor’s advice and went home to Rondepoort, near Krugersdorp, where my family was staying at the time, and there, thanks to the careful treatment of my kind doctor and the tender care of my wife I soon recovered my strength.

On the 25th of February I received a communication from my commando to the effect that General Buller had once more concentrated his forces on Colenso and that heavy fighting was going on. The same evening I also had a telegram from President Kruger, urging me to rejoin my commando so soon as health would allow, for affairs seemed to have taken a critical turn. The enemy appeared to mean business this time, and our commando had already been compelled to evacuate some very important positions, one of which was Pieter’s Heights.

Then the news came from Cape Colony that General Piet Cronje had been surrounded at Paardeberg, and that as he stubbornly refused to abandon his convoy and retreat, he would soon be compelled by a superior force to surrender.

The next morning I was in a fast train to Natal, accompanied by my faithful adjutant. Rokzak. My other adjutant, Du Preez, had meantime been ordered to take a reinforcement of 150 men to Pieter’s Heights, and was soon engaged in a desperate struggle in the locality situated between the Krugersdorpers’ and the Middleburgers’ positions. The situation was generally considered very serious when I arrived near the head laager at Modderspruit late in the evening of the 27th of February, unaware of the unfavourable turn things had taken during the day at Paardeberg, in the Cape Colony, and on the Tugela. We rode on that night to my laager at Potgietersdrift, but having to go by a roundabout way it took us till early next morning before we reached our destination. The first thing I saw on my arrival was a cart containing ten wounded men, who had just been brought in from the fighting line, all yellow with lyddite.

Field-cornet P. van der Byl, who came fresh from the fight near Pieter’s Heights, told me that these burghers had been wounded there. I asked them what had happened and how matters stood. “Ah, Commandant,” he replied, “things are in a very bad way! Commandant Du Preez and myself were called to Pieter’s Heights three days ago, as the enemy wanted to force their way through. We were in a very awkward position, the enemy storming us again and again; but we held our own, and fired on the soldiers at 50 paces. The English, however, directed an uninterrupted gun fire at our commandos, and wrought great havoc. Early Sunday morning the other side asked for a truce to enable them to bury their dead who were lying too close to our positions to be got at during the fighting. Many of their wounded were lying there as well, and the air was rent during 24 hours with their agonised groans, which were awful to hear. We, therefore, granted an armistice till 6 o’clock in the evening.” (This curiously coincided in time with Lord Roberts’ refusal to General Piet Cronje at Paardeberg to bury his dead).

“The enemy,” continued the field-cornet, “broke through several positions, and while we were being fired at by the troops which were advancing on us, we were attacked on our left flank and in the rear. Assistant-Commandant Du Preez, and Field-Cornet Mostert, were both severely wounded, but are now in safe hands. Besides these, 42 of our burghers were killed, wounded, or taken prisoners; we could only bring 16 of our wounded with us. The Krugersdorpers, too, have suffered severely. The enemy has pushed through, and I suppose my burghers are now taking up a position in the “randten” near Onderbroekspruit.”

Here was a nice state of things! When I had left my commando 15 days previously, we had had heavy losses in the battle of Vaalkrantz, and now again my burghers had been badly cut up. We had lost over 100 men in one month.

But there was no time to lose in lamenting over these matters, for I had just received information that General P. Cronje had been taken prisoner with 4,000 men. The next report was to the effect that the enemy was breaking through near Onderbroekspruit, and that some burghers were retiring past Ladysmith. I was still in telegraphic communication with the head laager, and at once wired to the Commandant-General for instructions. The answer was:—

“Send your carts back to Modderspruit (our headquarters) and hold the position with your mounted commandos.”

The position indicated was on the Upper Tugela, on a line with Colenso. My laager was about 20 miles away from the head laager; the enemy had passed through Onderbroekspruit, and was pushing on with all possible speed to relieve Ladysmith, so that I now stood in an oblique line with the enemy’s rear. I sent out my carts to the south-west, going round Ladysmith in the direction of Modderspruit. One of my scouts reported to me that the Free State commandos which had been besieging Ladysmith to the south, had all gone in the direction of Van Reenen’s Pass; another brought the information that the enemy had been seen to approach the village, and that a great force of cavalry was making straight for us.

General Joubert’s instructions were therefore inexplicable to me, and if I had carried them out I would probably have been cut off by the enemy. My burghers were also getting restless, and asked me why, while all the other commandos were retiring, we did not move. Cronje’s surrender had had a most disheartening effect on them; there was, in fact, quite a panic among them. I mounted a high kopje from which I could see the whole Orange Free State army, followed by a long line of quite 500 carts and a lot of cattle, in full retreat, and enveloped in great clouds of red dust. To the right of Ladysmith I also noticed a similar melancholy procession. On turning round, I saw the English in vast numbers approaching very cautiously, so slowly, in fact, that it would take some time before they could reach us. Another and great force was rushing up behind them, also in the direction of Ladysmith.

It must have been a race for the Distinguished Service Order or the Victoria Cross to be won by the one who was first to enter Ladysmith. We knew that the British infantry, aided by the artillery, had paved the way for relief, and I noticed the Irish Fusiliers on this occasion, as always, in the van. But Lord Dundonald rushed in and was proclaimed the hero of the occasion.

Before concluding this chapter I should like to refer to a few incidents which happened during the Siege of Ladysmith. It is unnecessary to give a detailed description of the destruction of “Long Tom” at Lombardskop or the blowing up of another gun west of Ladysmith, belonging to the Pretoria Commando. The other side have written enough about this, and made enough capital out of them; and many a D.S.O. and V.C. has been awarded on account of them.

Alas, I can put forward nothing to lessen our dishonour. As regards the “Long Tom” which was blown up, this was a piece of pure treachery, and a shocking piece of neglect, Commandant Weilbach, who ought to have defended this gun with the whole of his Heidelberg Commando, was unfaithful to his charge. The Heidelbergers, however, under a better officer, subsequently proved themselves excellent soldiers. A certain Major Erasmus was also to blame. He was continually under the influence of some beverage which could not be described as “aqua pura”; and we, therefore, expected little from him. But although the planning and the execution of the scheme to blow up “Long Tom” was a clever piece of work, the British wasted time and opportunity amusing themselves in cutting out on the gun the letters “R.A.” (Royal Artillery), and the effect of the explosion was only to injure part of the barrel. After a little operation in the workshops of the Netherlands South African Railway Company at Pretoria under the direction of Mr. Uggla, our gun-doctor, “Long Tom’s” mouth was healed and he could spit fire again as well as before. As to the blowing up of the howitzer shortly after, I will say the incident reflected no credit on General Erasmus, as he ought to have been warned by what happened near Lombardskop, and to have taken proper precautions not to give a group of starving and suffering soldiers an opportunity of penetrating his lines and advancing right up to his guns.

Both incidents will be an ugly blot on the history of this war, and I am sorry to say the two Boer officers have never received condign punishment. They should, at any rate, have been called before the Commandant-General to explain their conduct.

The storming of Platrand (Cæsar’s Camp), south-east of Ladysmith, on the 6th of January, 1900, also turned out badly for many reasons. The attack was not properly conducted owing to a jealousy amongst some of the generals, and there was not proper co-operation.

The burghers who took part in the assault and captured several forts did some splendid work, which they might well be proud of, but they were not seconded as they should have been. The enemy knew that if they lost Platrand, Ladysmith would have to surrender; they therefore defended every inch of ground, with the result that our men were finally compelled to give way. And, for our pains, we sustained an enormous loss in men, which did not improve in any way the broken spirit of our burghers.

CHAPTER XII

THE GREAT BOER RETREAT.

There was clearly no help for it, we had to retreat. I gave orders to saddle up and to follow the example of the other commandos, reporting the fact to the Commandant-General. An answer came—not from Modderspruit this time, but from the station beyond Elandslaagte—that a general retreat had been ordered, most of the commandos having already passed Ladysmith, and that General Joubert had gone in advance to Glencoe. At dusk I left the Tugela positions which we had so successfully held for a considerable time, where we had arrested the enemy from marching to the relief of Ladysmith, and where so many comrades had sacrificed their lives for their country and their people.

It was a sad sight to see the commandos retreating in utter chaos and disorder in all directions. I asked many officers what instructions they had received, but nobody seemed to know what the orders actually were; their only idea seemed to be to get away as quickly as possible.

Finally, at 9 o’clock in the evening we reached Klip River, where a strange scene was taking place. The banks were crowded with hundreds of mounted men, carts and cattle mingled in utter confusion amongst the guns, all awaiting their turn to cross. With an infinite amount of trouble the carts were all got over one at a time. After a few minutes’ rest I decided on consulting my officers, that we should cross the river with our men by another drift further up the stream, our example being followed by a number of other commandos.

I should point out here that in retreating we were going to the left, and therefore in perilous proximity to Ladysmith. The commandos which had been investing the town were all gone; and Buller’s troops had already reached it from the eastern side, and there was really nothing to prevent the enemy from turning our rear, which had perforce to pass Ladysmith on its way from the Tugela. When we had finally got through the drift late that evening, a rumour reached us that the British were in possession of Modderspruit, and so far as that road was concerned, our retreat was effectually cut off.

Shortly before the War, however, the English had made a new road which followed the course of the Klip River up to the Drakensbergen, and then led through the Biggarsbergen to Newcastle. This road was, I believe, made for military purposes; but it was very useful to us, and our wagons were safely got away by it.

Commandant D. Joubert, of the Carolina Commando, then sent a message asking for reinforcements for the Pretoria laager, situated to the north-west of Ladysmith. It was a dark night and the rain was pouring down in torrents, which rendered it very difficult to get the necessary burghers together for this purpose.

I managed, however, to induce a sufficient number of men to come together, and we rode back; but on nearing the Pretoria Laager, I found to my dismay that there were only 22 of us left. What was to be done? This handful of men was of very little use; yet to return would have been cowardly, and besides, in the meantime our laager would have gone on, and would now be several hours’ riding ahead of us. I sent some burghers in advance to see what was happening to the Pretoria Laager. It seemed strange to me that the place should still be in the hands of our men, seeing that all the other commandos had long since retired. After waiting fully an hour, our scouts came back with the information that the laager was full of English soldiers, and that they had been able to hear them quarrelling about the booty left behind by the burghers.

It was now two o’clock in the morning. Our Pretoria comrades were apparently safe, and considerably relieved we decided to ride to Elandslaagte which my men would by that time have surely reached. Our carts were sooner or later bound to arrive there, inasmuch as they were in charge of a field-cornet known to us as one of our best “retreat officers.” I think it was splendid policy under the circumstances to appoint such a gentleman to such a task; I felt sure that the enemy would never overtake him and capture his carts. We followed the main road, which was fortunately not held by the enemy, as had been reported to us. On the way we encountered several carts and waggons which had been cast away by the owners for fear of being caught up by the pursuing troops. Of course the rumour that this road was in possession of the English was false, but it increased the panic among the burghers. Not only carts had been left behind, but, as we found in places, sacks of flour, tins of coffee, mattresses and other jettison, thrown out of the carts to lighten their burden.

On nearing Elandslaagte we caught up the rear of the fleeing commandos. Here we learned that Generals Botha and Meyer were still behind us with their commandos, near Lombardsdorp. We off-saddled, exhausted and half starving. Luckily, some of the provisions of our commissariat, which had been stored here during the Ladysmith investment, had not been carried away. But, to our disgust, we found that the Commissariat-Commissioner had set fire to the whole of it, so we had to appease our hunger by picking half-burned potatoes out of a fire.

At 7 o’clock next morning General Botha and his men arrived at Elandslaagte and off-saddled in hopes of getting something to eat. They were also doomed to disappointment. Such wanton destruction of God’s bounty was loudly condemned, and had Mr. Pretorius, the Commissioner of Stores, not been discreet enough to make himself scarce, he would no doubt have been subjected to a severe “sjamboking.” Later in the day a council of war was held, and it was decided that we should all stay there for the day, in order to stop the enemy if they should pursue us. Meantime we would allow the convoys an opportunity of getting to the other side of the Sunday River.

The British must have been so overjoyed at the relief of Ladysmith that Generals Buller and White did not think it necessary to pursue us, at any rate for some time, a consideration for which we were profoundly grateful. Methinks General Buller must have felt that he had paid a big price for the relief of Ladysmith, for it must have cost him many more lives than he had relieved. But in that place were a few Jingos (Natal Jingos) who had to be released, I suppose, at any costs.

My burghers and I had neither cooking utensils nor food, and were anxious to push forward and find our convoys; for we had not as yet learned to live without carts and commissariat. At dusk the generals—I have no idea who they were—ordered us to hold the “randjes” south of the Sunday River till the following day, and that no burghers were to cross the river. This order did not seem to please the majority, but the Generals had put a guard near the bridge, with instructions to shoot any burghers and their horses should they try to get to the other side; so they had perforce, to remain where they were. Now I had only 22 men under my command, and I did not think these would make an appreciable difference to our fighting force, so I said to myself: “To-night we shall have a little game with the generals for once.”

We rode towards the bridge, and of course the guard there threatened to fire on us if we did not go back immediately. My adjutant, however, rode up and said: “Stand back, you ——! This is Commandant Viljoen, who has been ordered to hurry up a patrol at ——” (mentioning some place a few miles away) “which is in imminent danger of being captured.”

The guards, quite satisfied, stepped back and favoured us with a military salute as we rode by. When we had been riding a little way I heard someone ask them what “people” they were who had passed over the bridge, and I caught the words: “Now you will see that they will all want to cross.”

I do not contend I was quite right in acting in this insubordinate manner, but we strongly objected to being put under the guard of other commandos by some one irresponsible general. I went on that night till we reached the Biggarsbergen, and next day sent out scouts in the direction of the Drakensbergen to inquire for the scattered remains of my commando. The mountains were covered with cattle from the laagers about Glencoe Station. The Boers there were cooking food, shoeing their horses, or repairing their clothes; in fact, they were very comfortable and very busy. They remarked: “There are many more burghers yonder with the General; we are quite sure of that.”… “The Commandant-General is near Glencoe and will stop the retreating men.”

In short, as was continually happening in the War, everything was left to chance and the Almighty. Luckily General Botha had deemed it his duty to form a rearguard and cover our retreat; otherwise the English would have captured a large number of laagers, and many burghers whose horses were done up. But, whereas we had too little discipline, the English had evidently too much. It is not for me to say why General Buller did not have us followed up; but it seems that the British lost a splendid chance.

Some days went by without anything of note happening. My scouts returned on the third day and reported that my commando and its laager had safely got through, and could be expected the next day. Meanwhile I had procured some provisions at Glencoe, and for the time being we had nothing to complain about.

I was very much amused next day to receive by despatch-rider a copy of a telegram from Glencoe sent by General Joubert to General Prinsloo at Harrismith (Orange Free State) asking for information regarding several missing commandos and officers, amongst whom my name appeared, while the telegram also contained the startling news that my commando had been reported cut up at Klip River and that I had been killed in action! This was the second time that I was killed, but one eventually gets used to that sort of thing.

I sent, by the despatch-rider, this reply:—

“I and my commando are very much alive!” Adding: “Tell the General we want four slaughter oxen.”

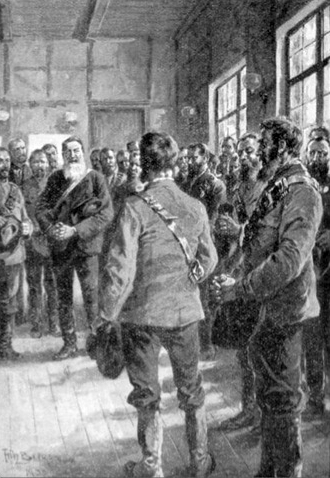

The following day I received orders to attend a council of war which was to be held at Glencoe Station. The principal object of this gathering was to discuss further plans of operation, to decide as to where our next positions were to be taken, and where the new fighting line would be formed.

We all met at the appointed time in a big unoccupied hall near Glencoe Station, where General Joubert opened the last council that he was to conduct in this world. Over 50 officers were present and the interest was very keen for several reasons. In the first place we all desired some official information about the fate of General Cronje and his burghers at Paardeburg, and in the second place some expected to hear something definite about the intervention of which so much had been said and written of late. In fact many thought that Russia, France, Germany or the United States of America would surely intervene so soon as the fortunes of war began to turn against us. My personal opinion was stated just before the war at a public meeting, held in Johannesburg, where I said: “If we are driven to war we must not rely for deliverance on foreign powers, but on God and the Mauser.”

Some officers thought we ought to retire to our frontiers as far as Laing’s Nek, and it was generally believed that this proposal would be adopted. According to our custom General Joubert opened the council with an address, in which he described the situation in its details. It was evident that our Commandant-General was very low-spirited and melancholy, and was suffering greatly from that painful internal complaint which was so soon to put an end to his career.

No less than eleven assisting commandants and fighting generals were present, and yet not one could say who was next in command to General Joubert. I spoke to some friends about the irregularities which occurred during our retreat from Ladysmith: how all the generals were absent except Botha and Meyer, while the latter was on far from good terms with General Joubert since the unfortunate attack on Platrand. This was undoubtedly due to the want of co-operation on the part of the various generals, and I resolved if possible, to bring our army into a closer union. I therefore proposed a motion:—

“That all the generals be asked to resign, with the exception of one assistant commandant-general and one fighting general.”

Commandant Engelbrecht had promised to second my proposal, but when it was read out his courage failed him. The motion, moreover, was not very well received, and when it was put to the vote I found that I stood alone, even my seconder having forsaken me. As soon as an opportunity presented itself I asked General Joubert who was to be second in command. My question was not answered directly, but egged on by my colleagues, I asked whether General Botha would be next in command. To this he replied: “Yes, that is what I understand—.”

And if I am not mistaken, this was the first announcement of the important fact that Botha was to lead us in future.

Much more was said and much arranged; some of the commandos were to go to Cape Colony and attempt to check the progress of Lord Roberts, who was marching steadily north after Cronje’s surrender. Finally each officer had some position assigned to him in the mountain-chain we call the Biggarsbergen. I was placed under General Meyer at Vantondersnek, near Pomeroy, and we left at once for our destination. From this place a pass leads through the Biggarsbergen, about 18 miles from Glencoe Station.