Editor’s note: The following comprises the first chapter of Seven Roman Statesmen of the Later Republic, by Sir Charles Oman (published 1902).

I. The Later Days of the Roman Republic

There was a time, not so very long ago, when the taunt was true that history was written as if it were a mere string of anecdotal biographies of great men. But for the last forty years the pendulum has been swinging so much in the other direction, that it has become necessary to enforce the lesson that the biographies of great men are, after all, a most important part of history. It is well to have conceptions of the streams of tendency and the typical developments of every age, but the blessed word “evolution” will not account for everything, and it is absurd to neglect the influence of the great personalities.

Roman history in particular has been so much treated of late years as a mere example of constitutional growth and degeneration, or as a bundle of interesting administrative and legal details, that it seems not out of place to recall that other aspect of it which was more familiar to elder generations, and to look at it for a moment from the personal and biographical point of view, with Plutarch before us as well as Mommsen and Marquardt’s Staatsrecht and Staatsverwaltung.[1]

This is all the more rational because in the last century of the Roman Republic we find ourselves in a time of dominating personalities. In Rome’s earlier days this was conspicuously not the case, and her history was (as has been truly said) the history of great achievements done by men who were themselves not great. But from the Gracchi onward we come to a period in which individuals make and mar the course of the times, when the doings of a Sulla and a Caesar, or even of a Marius and a Pompey, form the main determining element in the history of the day.

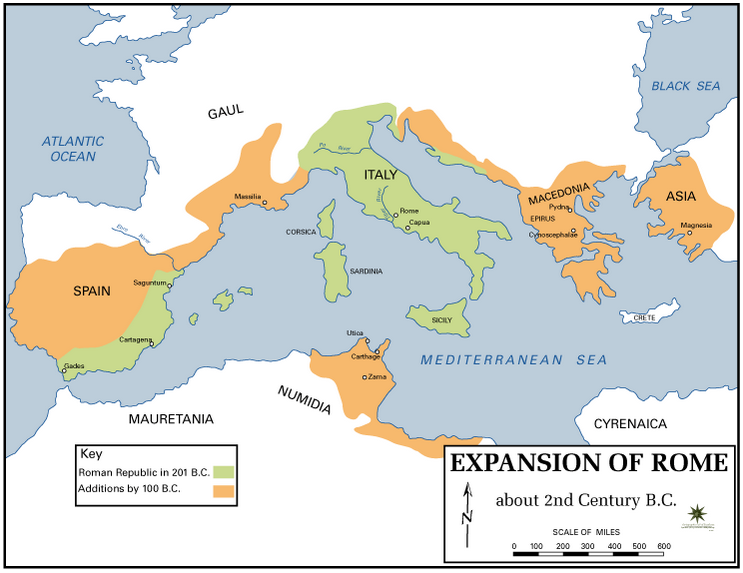

From the end of the Second Punic War down to the time of the Gracchi, Roman history is very monotonous and uninteresting to the reader. It is little more than the record of the haphazard building up of an empire, by the unintentional and unsystematic conquest of various disconnected districts round the Mediterranean. The wars are uninteresting, because they are waged by men who are little more than names to us ; the commander, be he a Plamininus or a Mummius, disappears from the historical stage when his consulship is over, and is lost to view once more in the ranks of an impersonal senate. Even the younger Scipio Africanus, who has to serve as a hero in these times for want of a better, soon palls upon us ; he stays in our mind only as a vague impersonation of civic virtue and somewhat cold-blooded moderation.

After B.C. 133 all is different; at last we have living, interesting, individual men to deal with; the names of Tiberius Gracchus, or Sulla, or Caesar are not remembered merely as connected with files of laws or lists of battles. At the same time both the internal and the external history of Rome becomes of absorbing interest. Externally the question arises whether the sporadic and ill-compacted empire built up in the last hundred years shall endure, or whether it shall be swept away by the brute force of the Cimbri and Teutons, or carved in two by Mithradates. Looking at the growing imbecility of Roman generals in that day, and the growing deterioration of Roman armies, it is not too much to say that, but for the intervention of two great personalities, the Roman Empire might have been swept away. If Marius had not appeared, a few more generals like Mallius and Caepio would have let the Cimbri and Teutons into Central Italy, and the exploits of Alaric in a.d. 410 might have been perpetrated by his remote ancestors. Similarly, but for Sulla the Nearer East might perchance have passed back, seven hundred years before the appointed time, into the hands of Oriental rulers, and have shared the fate which overtook Hellenistic Babylon and Bactria, by losing its touch with Western civilisation under a dynasty almost as thinly veneered with Greek culture as the Parthian Arsacidae or the Bactrian Scyths.

Internally the problems of Roman history during this period are quite as interesting. While the imperial city was fighting abroad, to maintain her existence and her suzerainty over the whole Mediterranean basin, she was being torn at home by a great constitutional struggle which pierced to the very roots of her being. This was the problem of determining with whom should reside for the future sovereignty, in the technical sense of the word, i.e. the actual supreme voice in the administration and law-making of the City and the Empire.

For the last two centuries there had existed a practical compromise between the theoretical omnipotence of the Public Assembly and the actual conduct of affairs by the Senate. This compromise was no longer possible, because Rome had developed from a city-state into an imperial state. Neither the Comitia nor the Senate was really competent to rule the new empire which they had acquired. If there was anything more preposterous than the theory of the Optimates (I mean that the government of the Roman world should be conducted by a small ring of narrow-minded noble families), it was certainly the opposite theory of the Democrats — that the mixed multitude of paupers and aliens into which the Comitia was fast degenerating, should supersede the senatorial oligarchy as administrators of the Empire. Complicated with this great constitutional question, as to where sovereignty should reside at Rome, were a number of social and economic questions, arising from the fact that the new commercial conditions of the Mediterranean world, which followed from the Roman conquests, were bringing about the ruin of the old farmer class which had for so many centuries formed the backbone of the state.

The details of the sporadic and never-ending wars in Spain, Macedonia, and the Hellenic East, which cover the period B.C. 200-140, hide the unwritten history of the most important changes in the social and economic conditions of Italy. In B.C. 200 Rome was still in the main a city-state of the old type, though she had already begun to acquire important transmarine domains. She was still a self supporting agricultural community, feeding herself on home-grown corn. Moreover, she might still be described as a narrow minded purely Italian town, little affected as yet, either in blood or in thought, by external influences. The elder Cato, with all his hard practical common sense, his stolidity, his passion for the life of the farm, and his contempt for the foreigner, was the typical Roman of that generation. By the last years of his old age he had seen a new world grow up, and complained that he was living in a city which he no longer understood.

For by B.C. 140 Rome was transformed. She was indubitably an imperial state, though she tried to shirk as long as possible the responsibilities of empire. Her population was no longer mainly a race of farmers dwelling on their own narrow acres; it was rapidly becoming divorced from the soil, and degenerating into a city-bred proletariat fed from abroad. Above all, Rome had to a large extent become cosmopolitan, having absorbed much Greek, or rather Graeco-Asiatic, culture and philosophy, and still more of Hellenistic luxury and demoralisation. The very blood of the people was getting largely diluted with a foreign strain, owing to the wholesale manumission of slaves.

While Rome had been transformed, her constitution remained perfectly unchanged, and the rude administrative machinery which had sufficed to manage a small community of farmers living close around the walls of the city, was being applied with a rigid and stupid formalism to the government of a widely extended empire.

Down to the Second Punic War, Rome had not acquired any provinces that tried very seriously her power to govern. Sicily and Sardinia were close at hand, in ready and constant communication with the city. They were actually visible from the headlands of Italy — mere broken-off fragments of the peninsula. An order could without much difficulty reach them in a few days: the Senate and People could make their will felt by governors and generals in districts so close to themselves.

The serious trial of the old municipal system of government, as applicable to the administration of distant dependencies, came after the acquisition of the Carthaginian dominions in Spain at the end of the Second Punic War. Separated from Italy by the still unsubdued coast-land of Southern Gaul, Spain could only be reached by a long sea voyage, which the Roman never loved, and which he rigidly eschewed at certain seasons of the year. The proconsuls in Spain got from the first a free hand such as no previous Roman governor had possessed.

It was a long time before any other provinces were added to the over-seas empire of the Senate and People. But at last they came, Macedonia and Africa both in 146, Asia in 133. It was the acquisition of these distant possessions that broke down the ancient power of the Senate to control the doings of the provincial magistrates. It was impossible to maintain a constant supervision over a governor at Gades, or Thessalonica, or Ephesus, or to get at him within any reasonable space of time. He had to be left very much to his own inspirations. It was but natural that the more ambitious proconsuls came to take advantage of this fact, and began to make or break treaties, to enter into wars, and to make conquests at their good pleasure. The Senate was sometimes provoked into disowning and annulling their doings, but not very often: when it did, the reason was not always creditable — as witness the case of Mancinus at Numantia.

Roughly, then, it may be said that by the third quarter of the second century before Christ, Rome had acquired an empire, but refused to take up any of the responsibilities of empire. The Senate still wished to control everything, but they could no more do so efficiently, owing to the mere difficulties of geographical distance, than in the eighteenth century the Bast India Company’s directors could control Clive or Warren Hastings. The proconsuls, on the other hand, could govern, but each only for his short year of office, and the work of each successor generally (and often deliberately) undid the work of his predecessor.

The responsibilities of empire, of which we have made mention were, in the main, threefold. The first was to provide good government within the provinces ; this the Roman Republic notoriously failed to secure. The constitution imposed on each conquered region, by the senatorial commission which drew up the lex provinciae after its annexation, was often wisely designed and reasonable. But when once it was formulated, there was no proper machinery for modifying it in accordance with the necessities of the times, or even for seeing that the proconsul did not violate its spirit by arbitrary tampering with the edictum tralaticium, the supplementary code which he could issue and vary at his own pleasure. All through the second century the control of the Senate was growing weaker, and it seemed that the wish as well as the power to check misgovernment was disappearing. The natural result was that the type of proconsul steadily deteriorated, as the probability of impunity for abuse of authority grew greater. Expedients like the establishment of the special court De Repetundis for the repression of financial maladministration were practically useless. To be effective, it would have required an active public prosecutor, ready to investigate every returning magistrate’s record, and a bench of judges absolutely beyond the breath of suspicion. But Roman usage entrusted all prosecutions to private initiative, and the court which tried the accused was so much swayed by personal and party bias that from the first there were scandals in its working. When a condemnation did occur, it was generally whispered that the convicted magistrate was suffering for some old political escapade at home, rather than for mere maladministration abroad.

The second of the responsibilities of empire, which Rome seemed unable to discharge, was the duty of keeping the police of the high seas and suppressing piracy. This task had in earlier centuries been to some extent discharged by the old naval powers — Carthage in the west, Macedon and Egypt in the east. Rome had now destroyed Carthage and Macedon, and the Ptolemies had sunk into hopeless imbecility and decay. The Romans would not keep up a permanent national fleet, both because it was expensive, and because they themselves disliked the sea. Hence the Mediterranean swarmed with pirates in a way that had never before been seen. The poorer and wilder maritime races took to piracy en masse, and almost strangled commerce. The Balearic Islanders swept the western seas; the unsubdued Dalmatians, the Adriatic; the Cretans, the Aegean; the Pamphylians and Oilioians — the most numerous and reckless of all these bands — had almost taken possession of the waters of the Levant. Their pirate squadrons went out a hundred vessels strong, levied blackmail on whole regions, and often made descents on cities within the boundaries of the Roman empire. The Senate only resented their outrages by fits and starts. If they grew too insolent, a squadron was sometimes sent against them, but it was seldom composed of vessels equipped and manned from Italy. The ordinary method was to requisition a fleet from the maritime allies of the state, who rendered unwilling and inefficient service. Hence it came to pass that though many Roman expeditions had been sent against the pirates, and several commanders had celebrated triumphs over them, the evil was not removed, and the Mediterranean did not become really safe for imperial commerce till the great naval campaign of Pompey in B.C. 67.

The third great responsibility which the Romans assumed, when they annexed great and remote provinces, was that of protecting the civilised world from the outer barbarian. The conquests of Spain and Macedonia made them the neighbours of scores of wild tribes, whom the Carthaginians in the one and the kings of the house of Antigonus in the other peninsula had been wont to drive back and to keep in check. The Roman, their heir by right of conquest, discharged this duty very spasmodically and inefficiently. The main reason for this was the deep-rooted dislike of distant and prolonged foreign service among the inhabitants of Italy. The people had comprehended, fifty years before, the need for universal conscription and long service in such crises as the Second Punic War. They could not see things in the same light when there was a call for troops to keep back Pseonian or Illyrian raids on Upper Macedon, or Lusitanian raids on Baetica. They grumbled and rioted every time that a new legion had to be raised. This made the Senate chary of calling out conscripts, or keeping them long on foreign service. But finally, the crisis always grew so dangerous that the hated levy had at last to be raised. Nothing can better illustrate the dislike of the Roman populace for the lingering and bloody wars of Spain, than the fact that twice in the middle years of the century (in 151 and in 138 B.C.) tribunes actually arrested and imprisoned consuls who persisted in enforcing the conscription, when public opinion was adverse to a new Spanish campaign. Yet the condition of the Roman borders in the Iberian peninsula was undoubtedly such that these levies were necessary. The Celtiberian and Lusitanian tribes were so warlike and turbulent that the frontier could never stand still. Raids had to be punished by retaliatory expeditions. The tribe that had been chastised would not remain quiet till it had been actually annexed; and so the process went on, for beyond each marauding clan lay another and a fiercer robber tribe. The whole peninsula was like the Afridi and Waziri frontier of North-Western India at the present day, and by advancing their boundary-marks the Romans only changed the names of their enemies. There was no finality till the Atlantic was reached, and the last Galician and Cantabrian mountaineers maintained their ferocious independence till the days of Julius Caesar and Augustus. In the Balkan peninsula the state of affairs was much the same under the later Republic, though the Triballi and Scordisci and Paeonians were not such formidable foes as the Spaniards. Macedon was never really free from northern inroads till the days of the empire. And in the East, when annexations had once begun in Asia, similar troubles, first with Galatians and Isaurians, and later with the formidable horse-bowmen of Parthia, came pouring in upon the perplexed senatorial oligarchy, which tried to govern an empire without an imperial outfit of army, navy, and civil service.

The Roman world, in short, was badly governed and badly defended: the provinces were steadily decreasing in wealth and resources from the moment that they were annexed. And since Italy and Rome herself were — as we shall see — tending to internal decay, though certain individual Romans and Italians were drawing huge profits from the newly acquired empire, the whole Mediterranean world seemed doomed to retrogression and collapse. It is possible that the Republic might have been demolished, if there had arisen against it any really formidable and well-equipped enemy. But the outer world was singularly destitute of strong men at this period. Jugurtha and Mithradates, in spite of all the trouble that they gave, were very third-rate personalities. And the one truly dangerous foe that marched against Rome during the last century of the Republic — the Cimbri and Teutons — represented mere brute force unguided by brains and strategy. At the last moment, when they had actually passed the Alps, they were annihilated by a general who possessed the art of improvising and handling a great army. It is curious to speculate what might have happened if not Marius, but some imbecile Optimate of the type of his predecessors Mallius and Caepio, had been in command at Aquae Sextiae or on the Raudian Plain. But Europe escaped the premature coming of the Dark Ages, and the black cloud of barbarism from the north having passed away, the men of the later Republic were left free to work out their own problems in their own unhappy way, in sedition, conspiracy, civil war, and proscription, till the coining of that great personality who showed the way — a bad way at the best — out of the hopeless deadlock into which Rome had fallen.

But ere Julius Caesar appeared there were not one but many Romans who saw well enough that the Roman world was out of joint, and tried, each in his more or less futile fashion, to set it right. With some of these statesmen it is our task to deal. Their successive biographies show well enough the course of the whole history of the later Republic; there is no gap between man and man; Sulla as a boy may have witnessed the violent end of Caius Gracchus: Julius Caesar as a boy did certainly witness and well-nigh suffer in the proscriptions of Sulla. The seven lives between them completely cover the last century of Rome’s ancien régime.

______________________________

[1] Titles of works by the respective authors on Roman constitutional law and Roman administrative law.

5

Great find, PG. We do see lots of parallels between Rome and the US. I also think that most good histories have no choice but to focus on “big names.” I mean, we can read about the life of a farmer in the ancient world, and it would be interesting, but not so different from all the other farmers. We do not need to read about them all. But to read about an Alexander, Julius, Constantine, etc. is interesting.

As Gen-X Americans, we know all too well what it is to be “badly governed and badly defended.”