Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The Sky Is My Witness, by Capt. Thomas Moore, Jr., U.S.M.C.R. (published 1943).

Midway Island! One and a half square miles of it. One and a half square miles of sand and coral surrounded by barbed wire and the sea; one and a half square miles of bleak and open ground, flattened by the sweeping winds, washed by driving rains, and burning beneath a tyrant sun; one and a half square miles populated only by men in uniform and a variety of pelicans; one and a half square miles of guns, guns, guns, ready and waiting to go off.

When we arrived at the air base, I found it to be much larger than I had expected. It was fitted with concrete runways that stretched as long as a mile in length. In the pits alongside the field stood our planes, kept in constant readiness. I could see mechanics hovering over them, seemingly nursing them. And even at that moment a patrol was circling the field preparing to land, while another flight was being readied for take-off.

At headquarters, our entire group of seven was as signed en masse to Marine Dive Bomber Squadron 241, to which Major Henderson was appointed as Commander. When these formalities were ended, Colonel Wallace, commanding all Marine aviation on the island, escorted us to the mess hall, a wooden, barrack-type structure that served also as saloon, social club, and church—depending upon the occasion and the weather. There we were introduced to our squadron mates.

A meet-the-boys attitude prevailed. Those who had been stationed here on the island but a few weeks had been graduated from flying school a few weeks ahead of me, and these I knew and recognized. But there were others, with captains’ bars pinned to their collars, who were strangers. They replied to their names with a curt nod and a brief handshake, at the same time completely appraising us with one brief squint. Some of them had been stationed here for almost as long as six months, a period that was marked with the attack upon Pearl Harbor, the fall of the Philippines, Guam, and Wake Island. Now and again during that period, enemy warships had shelled the island, but these incidents had been minor. Thus, for those months they had done nothing but wait, wait for the full fury to strike Midway. Those months of waiting were written across their faces sharply and clearly; it did not make them look younger—but then, nothing that happened to us made us look younger.

In talking with these men I became aware that, beneath all the smiles and good humor, they were drawn tight as the strings of a finely tuned violin, and if one were to pluck these strings the result would be shattering and explosive. It was a conscious strain even to talk with them, always to say the right thing at the right time, to be firm in expressing an opinion, and yet inoffensive. I was unused to such rigid self-control, and when evening came and I went to the dugout to which most of our group had been assigned, Maurice Ward and I blew up at each other in an argument that almost ended in a fist fight.

It was just that the boys had all gone to the dugout ahead of me, and, quite naturally, the first to arrive had grabbed the choice sleeping locations—namely, the top bunks. So, when I stumbled down the narrow steps into our tiny underground hut and found that the top bunks were already occupied, I loudly disapproved of the arrangement. Because Major Henderson was there, I covered my temper with a lying smile, and made a stump speech for my rights.

Since Schlendering and Rollow said nothing, I turned on Ward and demanded that the four of us pick cards for the choice bunks. But Ward was adamant and ignoring. He continued to read his book though I shouted and ranted for fair play. When he did reply, it was with just a few quiet, biting words. Then we became more and more abusive of each other, but carefully so—Major Henderson was present. Jokingly, I made the statement that my commission was dated prior to his own, and so I outranked him; whereupon someone, attracted by the noise coming from our dugout, stuck his head inside and shouted, “Rank among second lieutenants is like virginity among whores! Shut up and go to sleep!”

We all laughed and the tension was broken. Ward said he just wanted to see how mad I’d get and then we agreed to pick cards. That almost started the battle all over again. I claimed that high card won in Brooklyn, while Ward said that low card won in Missouri. Major Henderson was smiling and finally handed down a decision. We picked cards and again I won. Then I told Ward that I didn’t want a top bunk anyway, so we all went to sleep as happy as homesick men can be.

The next morning a truck carried us to our planes. Waiting beside my ship I found a tall slim young Marine captain. We introduced ourselves again; we had met in the mess hall the day before but had forgotten each other’s names. He was Dick Fleming and he gave me the cockpit checkout on the SB2U.

The planes we flew were ancient fabric-covered SB2U’s, and they had not improved with age. In fact, though they were designated as dive bombers, they could not be dived safely at too steep an angle. We were all more than just a little worried about the prospect of having to use them in a real attack. The word was that new SBD’s would soon arrive, but the word was also worn with age.

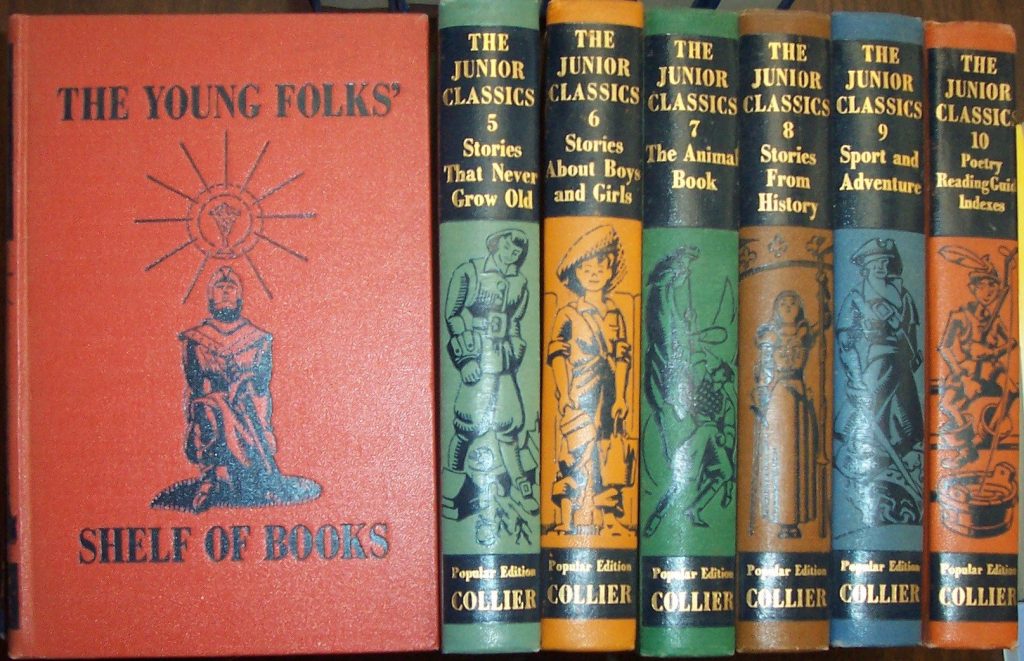

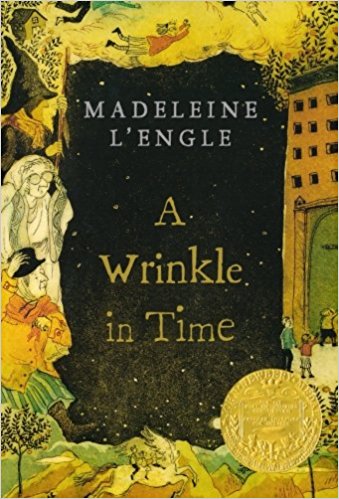

In our spare hours we tried to keep ourselves occupied in the best possible manner. The important thing was amusement. And because we couldn’t buy it, we improvised. We threw cards, played ping-pong, read books, and intoxicated the clumsy, bony gooney birds. They were our favorite amusement.

I bought a piano accordion from Captain Elmer Glidden and tore the stillness from the night with howling sound. Captain Armand De Lalio had another one sent to him from Pearl Harbor, and together we made everything but music. There was, however, one musician in the squadron. Captain Dick Fleming, an accomplished pianist before the war, rescued from us the ravaged reputations of many composers when he handled my accordion. So, a glee club was often assembled when things were dull, and while Mars’ minstrel played we sang ourselves to laughter.

We were defending an American outpost, which we had come a long way from home to defend. It was the middle of May. Our country had been at war for five months. Many of our comrades in arms had made the supreme sacrifice, and we in our turn were awaiting the moment when we, too, would be called upon at least to offer that sacrifice. But I must here note and mention that, though all these things held a very definite truth, we were, to say the least, unaware in the ultimate sense of what that truth concerned.

There was a time when we were gathered in the mess hall deploying through bottles of beer and the question of “Why the war?” was broached. The variety of opinions voiced at that session differed with almost each man present. But in no single opinion could I find any reason that was as strong as even the little pieces of steel we were so soon to face.

“We’re fighting because we were attacked. We’ve got to show them who’s boss.”

“Yeah? Well, the life of even one man is a hell of a price to pay for that kind of a show.”

“Ah, it’s a money war. We fight and they collect.”

“Is that so?”—from a banker’s son. “What the hell do you think I’m doing here?”

Of course, there were many who expressed no opinion. I like to think that they felt too deeply about it to say anything.

There was much mention, naturally, of the word “freedom” and much talk of “issues,” but they were intangibles. We spoke of them in that way. As for myself, I did not think too much about it. I had not yet actually seen men die for any of those things.

Toward the end of May a ship arrived at Midway carrying our long-promised new planes as well as ten or fifteen additional flyers to complement both our own squadron and the fighter squadron which had shared the field. At about the same time a contingent of Army Flying Fortresses also landed to operate from our base. A squadron of Navy P boats followed and immediately began a daily patrol. The appearance of these important reinforcements gave rise to wide speculation about the imminence of an enemy attack—after all, you never sharpen a knife unless you plan to use it. We had been engaged in daily maneuvers before, but from that date forward they were so realistically planned and executed that all previous maneuvers seemed more like games, now that we looked back.

It was some nights later, as we were preparing to turn in, when someone—I believe it was Maurice Ward— asked Major Henderson about the imminence of such an attack. As always, Major Henderson was objective. He told us his opinion in these words:

“The success of all our Pacific operations depends upon us—and, gentlemen, I make no understatement when I use the word us.” We are the shock troops that must meet any attack that may come. There is no one between us and the enemy. Remember that. We must recognize that responsibility, each and every one of us….”

I looked about our little underground room. So there was just us and others like us….

And who composed us?

Major Lofton P. Henderson [sic], age 39: Professional officer, graduate of the United States Naval Academy. All his interests in life had always been subjected to the military service. It was for such moments as these to which his life for more than twenty years had been dedicated.

Lieutenant Gilbert Schlendering, age 23: Quiet, a thinker, an intellectual. “I fight so that I can read what I want to read, and listen to what I want to listen to, and live as I wish to live.”

Second Lieutenant Maurice Ward, age 22: A tall, lanky boy from Kansas City, Missouri. I always thought of him as someone who had stepped from the college classroom straight to Midway, stopping only long enough to leave his books and change his clothes.

Second Lieutenant Jesse Rollow, age 24: Always good for a laugh, firm in his opinions, cocky, but sensitive; a good civilian trying to be a good soldier.

Second Lieutenant Thomas F. Moore, Jr., age 24: The eternal plebeian New Yorker no matter what the conditions or where the place.

That was part of us.

On the night of June 3 I returned from my alert station carrying some beer and cheese sandwiches from the mess hall. Two of these sandwiches were almost sodden with mustard because that was the way Major Henderson liked them. When I entered the dugout I found only the Major there. I was glad he was alone. He was like Father Woloch, a man you could talk to with no fear of being misunderstood.

There had been many nights like this before, but somehow this night was different. There was something in the air, I just felt it; we all felt it. No one knew what it was exactly, but whatever it was it made us feel more than a little nervous and more than a little tense. That was why I was glad to talk alone with Major Henderson. Though he always knew that come what may he must lead us all, he was never disturbed, nor had I ever seen him break the evenness of his temper. Talking with him always made me feel more calm.

On this night, over beer and cheese sandwiches, we talked about the enemy, the Japanese enemy. He spoke his opinion evenly and without passion; as always he was objective.

“They are like a horde of impudent germs that are trying to disease the world. The more you kill the less grows the danger. They must be made to suffer because only by suffering will they realize that the world is not afraid of them, and the only way to do that is to destroy enough of them so that those who live will realize that they must never play with fire again. Kill them, lots of them, and all their organs will burst like balloons. They have got to be killed as you kill a fly, without pity, without remorse.”

One by one, the other boys strolled in: first Schlendering, then Ward, then Rollow. We all talked together for a while and when we ran out of words Schlendering and Ward climbed up into their bunks to continue the books they had been reading, Major Henderson turned to writing a report, and Rollow and I carried on with a discussion of the baseball scores we had heard at the engineering tent. We did not know then that several of our Naval patrol planes had just returned to Midway after making contact with the enemy, and that the enemy was a Japanese flotilla on its way to attack and invade us.

About ten o’clock the light was extinguished and we turned in. There were all five of us in the dugout that night. All the beds were filled: Major Henderson, Jesse Rollow, Gil Schlendering, Maurice Ward, and myself. We were five.

Five.