Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Triggernometry: A Gallery of Gunfighters, by Eugene Cunningham (published 1934).

Sheriff Finley had a printed description of William P. Longley. He had studied that “flier” until he walked and rode with before his eyes a picture of a sinewy, quick-moving six-footer, dark of hair and eyes and soft youthful mustache, “going heavily-armed,” who “must be approached with caution,” because he was “a very dangerous man always ready to fight.”

Bill Longley could only guess that the sheriff recognized him through the thin mask of his alias — William Henry. Perhaps he did not even guess, at first, for Finley was “smooth people.” But as he and the sheriff became the closest of companions, drinking together, yarning by the hour of this and that, sitting down together to play seven-up, he proceeded on the basis that the sheriff did know him and was only trying to put him off his guard.

When Finley brought in two strangers and suggested a game of cards between them all, that night, Longley agreed. But he had a suspicion about the kind of game Finley intended. He went out and got on his horse. He made no stop until he reached the quaint German town of Fredericksburg.

Finley showed up in Fredericksburg. He still wanted a game of cards, it seemed. Once more Longley made and broke an engagement. He rode to Kerrville but left quickly, heading out for Edwards County. Sheriff Finley and a large posse followed, rounded up Bill’s camp and at dawn Finley hailed Longley, who jumped out of his blankets with a six-shooter in each hand. There was parleying, but it was death or surrender. And he had escaped the authorities before. He handed over his Colts to Finley.

This was late in ’73. Edmund J. Davis, last of the reconstruction governors, famous for his “nigger police” which had replaced the Texas Rangers, had troubles of his own. He was fighting bitterly the accession of Richard Coke to the governor’s chair. When Finley brought Longley into Austin, he was informed that no reward would be paid.

Sympathize for a moment with a shrewd, brave officer! The most dangerous man in Texas in his custody, captured after a long period of working up the case and after three attempts. Now, the thousand dollars he had expected was nonexistent. It was a sad day for Sheriff Finley! But when a relative of Longley’s came along and paid over five hundred dollars to Finley, to secure Bill’s release, the sun came out again. He could hardly be blamed for turning Longley loose, when the state’s chief executive refused to take him.

Longley went home — to Evergreen, not to Bell County. He moved on, once more the Fate-ridden outlaw. There were warrants out for him, for negroes killed at Old Evergreen. He had enemies interested in seeing him prosecuted. He says that he discussed with his father giving himself up and the old man shook his head drearily:

“It would bankrupt me even to try to clear you,” he told his son.

Longley put faith only in his six-shooters, after that. He was twenty-three — or in his twenty-third year. The huge-limbed boy had become a magnificent physical specimen, towering over six feet, weighing over two hundred pounds, but looking almost lean. A figure to take a man’s eye — or a woman’s…

He drifted into Frio County. A Mexican argued with him over a horse-trade and the argument ended with the roar of the Longley six-shooters punctuating, setting period to, the Longley objections. He was not above a grim sort of jest — as he proved when he rode up to the arm of William Baker, on Walnut Creek in Bastrop County.

“Mr. Baker,” said Bill innocently, “my name’s Baker, too. I reckon we’re kinfolks and I’d like to work for you.”

He got a job but when word came by the grapevine telegraph that Lee County had been cut off old Washington County and a brand-new sheriff named Jim Brown was on his trail, he called Baker to one side.

“Mr. Baker, I’ve got a confession to make,” he told the farmer. “I’m not really kinfolks of yours. I’m that hell-roaring Bill Longley you’ve heard so much about. I like a warm climate as much as the next man. But this weather is more than warm — it’s getting hot! I’ll be leaving you!”

November of 1875, by his own record of dates, found him working north of Waco at a gin. The big, dark laborer was known as Jim Patterson around McLennan County. He was not considered a bad egg, but George Thomas was. George was known to have killed some men. So when the gin-laborer had a ferocious fist-fight with the gunman and Thomas rode off the field promising to “smoke it” at their next meeting, public sentiment regarded “Patterson” as a walking dead man.

Longley rode up to Thomas that same night, where he sat his horse outside of a little store. He had waked the storekeeper and they were talking, plain in the moonlight.

“Well, Thomas,” said Longley, “this is our first meeting and I’m ready to settle our trouble.”

“All right!” Thomas grunted and whipped out his pistol. It was doubtless a fast McLennan County draw. But, somehow, the amazed storekeeper noted, “Patterson” had beat the gun-fighter to the draw. His gun barked in the quiet night. Thomas’ pistol fired only as he tumbled from the saddle. Three more bullets Longley sent into him. Then he apologized very courteously indeed, to the storekeeper, and rode out of that neighborhood.

At a Mexican ranch on the Medina near San Antonio, his horse was stolen and he killed the man who had taken it. He went on to Frio Cañon in Bandera County and the natural beauty of this lovely region affected even his fierce, restless heart. He was ready to settle down there for life.

But there was a hard case going by the name of Sawyer, with whom Longley grew quite intimate. When he found that Sawyer was cultivating him to learn if a reward were offered for him, with the idea of capturing him to earn it, he decided to turn the tables on the traitor. He got himself deputized to capture Sawyer, whom he knew to be a fugitive. He and Sawyer fought a fierce duel in the cedar brakes, Sawyer’s shot gun and pistol against Longley’s Colts.

Four bullets, Longley put into him, but Sawyer was a fighting man! He killed Longley’s horse and they continued the battle through the brush. Longley killed him, at last, when he had lodged thirteen balls in his body!

Again he moved on. He found a couple of men on the Castroville road who wanted to free a prisoner in Castroville jail. Longley still had some warrants given him by the sheriff at Uvalde. Warrants for King Fisher, John Wesley Hardin, and other notorious gunfighters. He posed as an officer, in Castroville, threw the sheriff offguard, captured him and released the prisoner. Then he rode eastward.

A deputy sheriff stopped him near Lockhart. He wanted to know by what authority Longley wore a pistol. Longley produced his sheaf of warrants. But the deputy could not show authority for his pistol. So Longley took it away from him.

He went through Lee County, under Sheriff Jim Brown’s very nose. In April of that year, Longley had taken furlough from Jim Baker’s Walnut Creek farm, to come back to Evergreen and interview Wilson Anderson. Word had come to Bill that Anderson and Cale Longley — Bill’s cousin — had ridden out together but Anderson had come home to report Cale killed by his horse.

Longley and Anderson met in an Anderson field. For once Bill had abandoned the sixes with which he was so deadly. He killed Anderson with a shotgun.

Now, he rode calmly through Lee County. Jim Brown must have been furious when he learned that Texas’ most notorious wanted man had shown him so little respect. But he could afford to let Longley have the laugh on him — his complete triumph was coming.

So was the one real love of Longley’s hunted life. A Madison County girl had once softened him, but Louvenia Jack, slender, pretty sixteen-year-old Desdemona to Longley’s dark, saturnine Othello, made him regret his wasted life, when he caught his first glimpse of her at her father’s farm house in Delta County.

He introduced himself to the Jacks as William Black, a Missourian and a roving man. When he said that he wanted work, old Jack was reminded that Parson Lay had a farm a mile beyond, and wanted someone to raise a crop on shares. That suited Longley. It suited Parson Lay, when they approached him. Longley did not precisely lay aside his Colts, beat his reddened blade into a plowshare, but he did farm.

His love-affair with Louvenia Jack ran into snags… There are two sides to this story. The Lays claimed that Longley, a hard case, grew unreasonably angry over a mere joke and murdered Lay. Longley insisted that the Lays objected to his attentions to the girl — favoring a man of the neighborhood — and also wanted to drive him away from the crop he had made. He quit the Lay farm, but the trouble was not over. Lay had him arrested, charged with threatening his life. Longley burned out of the little plank jail, rode to the Jack place. There he secured a double-barreled shotgun, went over to Lay’s and found the preacher milking cows. He killed him there with a load of turkey-shot.

He ran for the Red River and crossed into the Indian Territory. He had trouble with the Indians and was shot. A half-breed Cherokee girl nursed him until he could make his way to the house of a friend in Arkansas.

He went back to Evergreen, taking a couple of friends out of the custody of a deputy sheriff enroute. It needed only the magic of the Longley name behind the Longley six-shooter to jerk that deputy’s hands aloft. He rode on to Delta County to see Louvenia. Delta County knew, now, that the William Black who had killed Lay was really the desperado, Bill Longley. He could not stay there, with the country alive with officers searching for him. Back to Bell County he went, to that quiet, puzzled old man, who had hatched this fierce chick to amaze and discomfit him.

There was a reward of five hundred dollars on his head, for Lay’s killing. Sheriffs everywhere were poring over the famous description:

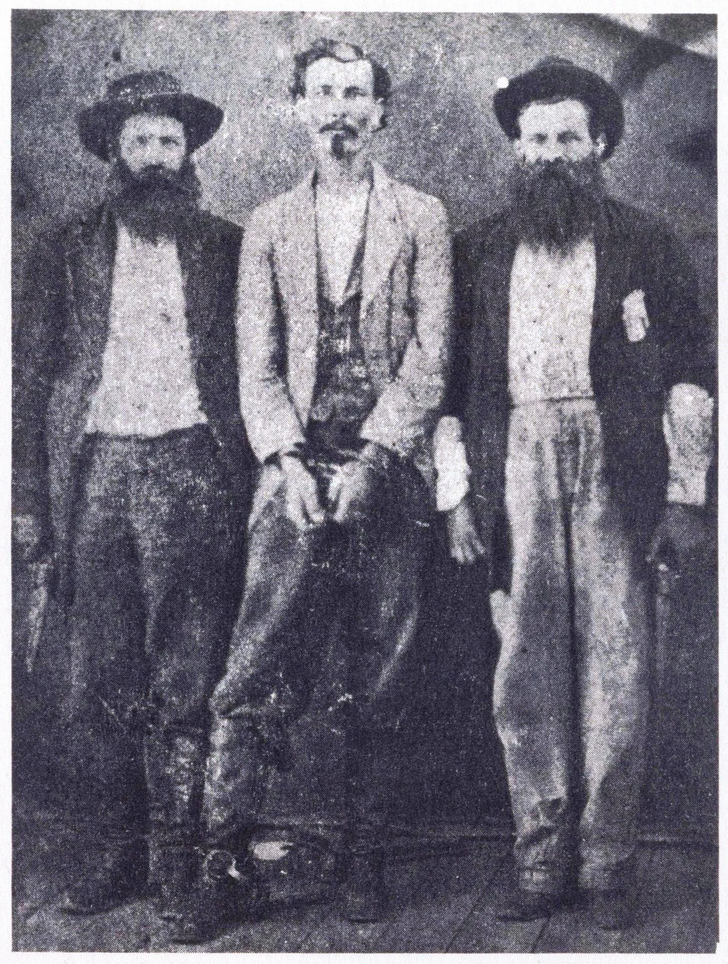

“…Six feet high; tolerably spare built; black hair, eyes and whiskers; slightly stooped in shoulders… can be recognized in a crowd of 100 by the keenness and blackness of his eyes… $250 being offered in Lee County.”

Always wandering…. De Soto Parish, ten miles over the Louisiana line from Texas, knew him in early ’77. A farm-hand again, known as William Jackson, and a great friend of young Constable Courtney, whom he often assisted in making arrests around Keatchie.

Courtney was a shrewd young officer. He was forever picking up the “fliers” describing famous criminals and studying them until his head was a very file of descriptive lists. There came a day when he received one on the “most desperate criminal in the Southwest” who was not — unfortunately! — just then in the Southwest, but a fugitive.

“Why, that fits Bill Jackson to a T!” Courtney said amazedly. But it seemed impossible that the quiet, fiddling, likable Jackson could be this lightning gun fighter, this killer of thirty-odd notches, the hell-roaring Bill Longley.

He began to investigate. At Nacogdoches, Texas, Sheriff Milt Mast was also thinking of Longley. He and Courtney exchanged some letters and Mast with Deputy Bill Burrows slipped across the Louisiana line one night in May, 1877. Mast could hardly believe that he was so close to an unsuspecting Longley. He looked up Courtney, who was expecting him.

“He’s hoeing in a piece of corn, about half a mile from the Gamble house,” Courtney told the Texas sheriff. “He may or may not have his pistol on. That’s something to risk. We’ll go out and you men wait in the house-yard. I’ll go into the field and tell Bill I want him to come help me arrest a bad negro. He’s done that so often, he probably won’t suspicion a thing. When we get into the yard, you’ll have to step out and cover him.”

Longley saw nothing strange about Courtney’s request. He had done the same thing many times. He walked into the Gamble yard and as they entered, Courtney dropped back a step. Captain Mast and Bill Burrows stepped out, pistols drawn. At the same moment Courtney rammed the muzzle of his pistol in Longley’s back.

Courtney, unloading his pistol, stepped up and tied Longley’s hands behind him, to the tune of Longley’s cursing. Mast and Burrows loaded the prisoner into a wagon. It was no time to hesitate. They wanted no fight over extradition. They ran Longley back into Texas and took him to Giddings. The Austin Statesman on June 21, 1877, recorded the capture and added that “he is credited with killing thirty-two men.”

He was tried for the murder of Wilson Anderson and pleaded self-defense. The trial began September 3, 1877. Longley claimed that he had no attorney and was given no chance to procure witnesses for the defense. The jury got the case the next day, deliberated for an hour and a half, and then brought in a verdict of guilty with sentence of hanging.

Appeals and other legal technicalities delayed execution of the sentence, but after a long wait in the Giddings and Galveston jails, on October 11, 1878, at 1:30 in the afternoon, Sheriff Jim Brown and his group of guards brought Longley out of his cell. He was quite cheerful as he got into the ambulance that was to convey him to the gallows.

Giddings was packed. The negroes who had feared him so were there by hundreds. It seemed impossible that their bogie-man was about to die. The ambulance came through the crowd and stopped at the gallows-steps. Longley got out and looked up at the scaffold. Nearly a hundred guards were massed about it, for Longley had many friends, even more sympathizers. There had been rumors of a rescue and those keen black eyes the reward fliers had so often noted roved over the sea of faces surrounding him. But no movement came from the spectators.

He shifted the cigar in his mouth and climbed the steps. They swayed a trifle and Longley grinned at Brown:

“Look out! The steps are falling!” he called. “I don’t want to get crippled!”

Sheriff Jim Brown was ill at ease. He had bought the old Longley homestead. He was living there, where this prisoner had lived. He looked down at the crowd from the gallows.

“This is Lee County’s first legal hanging, he said — then added fervently: “And I hope it will be the last!”

Longley was much calmer. He spoke briefly, without any of the rancor he had shown in letters written from Giddings jail. He had seen none of his family. In one letter he had remarked that his father had been forbidden under penalty of death to defend his son; claimed that Wilson Anderson was heavily-armed at the time of his killing and had made the first movement toward a weapon. In that letter he accused the authorities of admitting the testimony of “a sworn gang of cutthroats and murderers.” None of this was evident as he faced a noosed rope for the second time in his twenty-seven years.

The black cap was drawn over his face and the noose placed. The drop was great — about twelve feet. With the twang of the tautened rope, it slipped on the crossbeam. Longley landed on his feet, with the rope slack. The sheriff and a deputy lifted him while a man tightened the rope. Eleven minutes later three doctors pronounced him dead.

Perhaps it was this circumstance which roused speculation in certain minds. The rumor had gone abroad that Longley would be rescued by desperate allies. It had been hinted that the rescue would not be the crude, if spectacular, dash of armed horsemen against the sheriff’s party at the gallows-foot.

As the tale came to be repeated in the months that followed the digging of “the Longley grave” outside of the cemetery fence at Giddings, friends had persuaded the not-unwilling Jim Brown to clothe Longley in a sort of harness, which came up to protect the neck and permitted him to take that long drop, give a few realistic groans and kicks and be cut down, to vanish with darkness, after an empty coffin had been interred.

In the years since then, the story has lost nothing in the telling. Veraciously, men and descendants of men who knew Longley have described meetings with him, years after that murky October day of 1878 in Giddings. Against these stories (which are told of Billy the Kid and Jesse James, also) must be set the evidence of three doctors, who examined the dangling body. One doctor, we may concede, might have been persuaded. But when the almost incredible happens, when any three doctors of the same community are unanimous in their opinions about anything, it must be so. And there was no minority report concerning Bill Longley’s condition, after his drop from the gallows.

Except in the manner of his meeting it, there is nothing heroic about Bill Longley’s death. There was nothing heroic about his life, for that matter. But there was much that was tragic! Not even John Wesley Hardin was so much a creature of his times.

Longley met Hardin once and there was a card-game in which the younger man came off winner. Longley has left no record of that encounter and Hardin was never a man to give himself the worst of any report that he made.

But, whether or not Hardin’s account is correct, there is no doubt that Longley disliked Hardin, his rival in the Smoky Seventies for top-honors at gun-slinging. He went to his death bitter because he had received the death-sentence for killing Wilson Anderson, while Hardin escaped with a penitentiary-sentence for killing Charley Webb, the Brown County deputy sheriff. In Giddings Jail, October 29, 1877, he wrote Sheriff Milton Mast of Nacogdoches:

“You know what I told you about John Wesley Hardin, and myself, and all such cases. When the right ones jump a fellow they always take him in out of the wet. I told you that John Wesley Hardin would get picked up some time, for all that he and his friends have told it everywhere that he would never be captured alive.

“There never was a man so fast but what he found a man just a little faster than he was. But, then, Captain, you know that you and Bill Burrows got the dead-drop on me, and so did Lieutenant Armstrong get it on John Wesley Hardin. But, drop or no drop, John Wesley Hardin and myself now inhale the gentle breezes that flow through prison windows.

“Did you see the interview that was given out by John Wesley Hardin when he was first brought to Austin? He said that he had never had anything to do with Bill Longley, nor any such characters, and that he never had anything to do with anybody except gentle men of honor.

“Now, as a matter of information, I would like to know where these gentlemen of honor friends of his are now! They certainly are not in jail where the Honorable John Wesley is himself. I wonder if it is King Fisher, Brown Bowen, Bill Taylor, Gladden Ringer, Scott Cooley, Grisson and two or three dozen others whom I might name?”

He recounts the killings of Hardin and his clan, calling them cowardly murders by a gang, and continues:

“Hardin was afraid of Webb and when he killed him he took every cowardly advantage that it was possible to take. It seems that it was death by their law — the law of Hardin and his gang — for a man just simply to say that he was not afraid of Wesley Hardin, and poor Charley could not help saying that, for he was a man that was never known to tell a lie, and so one day when somebody asked him if he would tackle John Wesley Hardin, he said he would certainly do so if he had the necessary papers for his arrest…

“Now, I do not mean to say that Wes Hardin is not brave, but the woods in Texas are full of brave men, and I suspect that Hardin remembers at least one — and that is old Reagan, who captured him near Palestine several years ago. I heard that when Hardin got back to his crowd in the brush, he said: “

“ ‘Boys, don’t ever let Old Man Reagan get after you, for he is hell! I tell you!’…

“Captain Mast, I suspect that they will hang me. It is just as I have told you in previous letters and in course of conversation. I cannot and do not think hard of you for arresting me, but don’t you think it is rather hard to kill me for my sins, and give Wes Hardin only twenty-five years for the crimes he has committed?

“But I guess he would say it was none of my business.”

They were touchy about their reputations, the old gunfighters. And Longley, Hardin, Ben Thompson and King Fisher were the outstanding quartette in Texas of the ’70s, with little love lost between them.

Each was doomed to a tragic death but Bill Longley — the only one who met his Fate coming to him behind a badge of the Law, was perhaps least deserving of that end. For destiny made him the creature he was — one of the fierce, undisciplined Border Breed.

[…] (Continue to Part 2) […]