Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Defeat At Sea: The Struggle and Eventual Destruction of the German Navy, 1939-1945, by C. D. Bekker (published 1955).

See also: The Sinking of the Scharnhorst: A British Perspective

In 1943 the Allies rewarded Hitler for his shortsighted order,[1] which had been responsible not only for the U-boat losses whose sharp rise had virtually brought the U-boat war to an end, but also for the loss of a battle cruiser which had previously been considered one of the “lucky ships” of the Navy — the Scharnhorst.

On the morning of February 15, 1943, a senior naval officer was sitting waiting in the hall of the Hotel Adlon in Berlin when a page approached him.

“Herr Admiral Thiele?”

“Yes?”

“The Herr Grossadmiral would like to see you.”

A few minutes later Dönitz was shaking his visitor’s hand.

“I want to speak to you, Thiele, about the possibility of using the 1st Battle Group in North Norway.”

“You mean the Lützow and the Nürnberg, Herr Grossadmiral?”

“Yes, but apart from them I consider it necessary for the Tirpitz to go on operations once again. Finally, we must consider whether the Scharnhorst shouldn’t be sent to North Norway as well, assuming I can get Hitler to agree to it.”

“I believe that to be the only right thing to do.”

“In any case I have just been able to obtain Hitler’s full agreement to my intentions, that is, that the ships should no longer be subjected to such excessive precautions — at least pending their being sent into reserve. They will now be going out on operations, just as soon as a worth-while object and a chance of success turns up. The officer in command of a squadron sent to sea from now on will be able to act and fight entirely on his own initiative, without having to wait for special instructions from superior authority.”

Thiele looked up in astonishment. The older circle of officers, which had much appreciated the cautious conduct of Raeder, had been somewhat skeptical of the appointment of the “U-boat man,” Dönitz, as the new Chief of Naval Staff. But when the latter was able to succeed in something for which Raeder had always worked in vain — the reversal of Hitler’s “No risks” order for the big ships — this could only be welcomed.

“Well, that’s a decisive point,” he agreed. “It was always out of the question to fight successfully when you were bound by this crippling order.”

All the same Thiele made no attempt to conceal his opinion that a breakout by the heavy ships into the Arctic would be dangerous. For now in winter the polar night up there allowed a few hours of twilight only, around midday. The fundamentals of sea warfare were only too well grounded in Admiral Thiele’s experience, and with one of them he now raised a doubt in the mind of his chief.

“The risks of a night battle in those waters would be much greater for us than for the enemy, who in any case will have superior torpedo forces at his disposal, mainly destroyers and light cruisers.”

“But I demand similar action from my U-boats,” interposed Dönitz, somewhat impatiently.

“The Tirpitz is no U-boat, Herr Grossadmiral.”

On that point in fact the two admirals failed to reach agreement. Thiele did go to northern Norway to take over command of the 1st Battle Group, but scarcely had he been two days on board the Lützow when he was reappointed elsewhere. Clearly he was not thought enough of a daredevil.

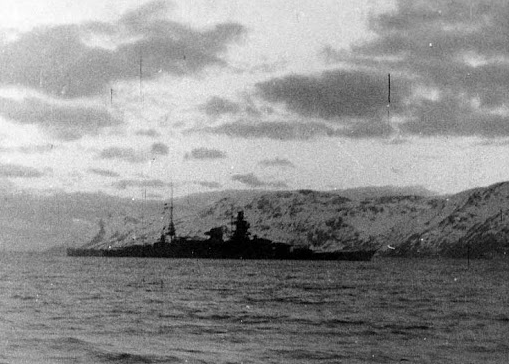

Meanwhile the relative strength of the forces in the north soon began to change. In proportion to Dönitz’s success in reversing bit by bit Hitler’s “unalterable decision” to put the big ships into reserve, so the advanced German weapon gained in strength and fighting power. Instead of the cruisers Lützow and Nürnberg of 10,000 and 6,000 tons respectively, which were withdrawn, Allied convoys in the Arctic carrying vital war material to Russia now found themselves suddenly threatened by the 41,000-ton battleship Tirpitz and the 31,000-ton battle cruiser Scharnhorst. These fast modern ships, from their bases in Alta and Kaa fjords, could emerge at any time and deal painful blows at the main supply line for the Russian land front.

The “fleet in being” was back again! By this expression is meant that a fleet, by its very presence within striking distance of his lines of communication, can force an enemy to adopt extensive strategic precautions. He must, for example, even when his opponents do not attack, always keep superior forces in readiness for the occasion which may arise. The English, therefore, devoted all their resources to mastering so permanent a threat. On September 9, 1943, the entire German fighting group, consisting of the Tirpitz, Scharnhorst, and ten destroyers, carried out the successful Spitsbergen operation. But shortly afterward some gallant Englishmen succeeded in taking two midget submarines through all the booms and defenses into the Tirpitz’s anchorage. Their special mines could not in fact destroy the great ship, but nevertheless they could put her out of action for a whole six months, which was what they did.

Now the Scharnhorst was alone the English could breathe again, for the situation had lost much of its menace. It could now be met by one superior battleship with a supporting force of cruisers and destroyers, with the consequence that the Admiralty decided to send bigger convoys than ever along the Arctic route to Murmansk. Meanwhile it had become winter again, and the conditions for operating the battle cruiser appeared even less favorable than when Admiral Thiele warned his chief about them. The ship must feel its way in the dark of the polar night. The secret of the British radar sets which had in the meantime been discovered made it quite clear that the enemy had the advantage of better gear than the old German radar sets mounted in the Scharnhorst. Moreover, from experience it was useless to expect support from the Luftwaffe, although it had established air supremacy in the sea areas adjacent to the Norwegian coast.

But meanwhile there were alarming reports coming in from the Eastern Front, where the German Army was engaged in savage defensive battles against the Russians attacking on several-hundred-mile-wide fronts. Each time a convoy full of American war material arrived in Russian harbors, its additional weight would be felt at the front a few weeks afterward.

This made Dönitz act. Whether the circumstances were favorable or not, he would attempt his utmost. He it was to whose face Hitler had cursed the Scharnhorst at the beginning of the year, and it was now up to him to prove that the ship still had a word to say.

A few days before Christmas, on December 20, 1943, the generals at headquarters listened to Dönitz as he made his report to Hitler: “Should there be any likelihood of a successful operation, the next Allied convoy in the north from England to Russia will be attacked by the Scharnhorst and her destroyer escort.”

On Christmas Eve, 1943, there was a call through the Scharnhorst’s loudspeaker system.

“Clear lower deck. Hands fall in on the quarterdeck!”

Everyone in the battle cruiser waited in suspense, knowing this was the “go,” the order to sail on operations. Since noon the ship had been at six hours’ and later at two hours’ notice for steam. Now steam was up; the anchor might be aweigh at any moment. Never before had the crew laid aft so quickly.

“The Captain has instructed me to tell you,” the first officer told the men, “that we are going to sea this evening for the destruction of an enemy convoy. According to reports a heavily laden convoy is now on its way to Murmansk. We must prevent its arrival there, and we shall in this way be helping our comrades on the Eastern Front who are at this moment engaged in one of the heaviest battles of the war.”

Later, when the ship was already under way, a signal was received in which Dönitz set out the problem in brief terms: Make bold and skillful use of the tactical situation. The fight is not to be half finished. The superior gun power of the Scharnhorst is to be used, and destroyers sent in to the attack. Use own judgment in breaking off action. Important to do this on encountering superior forces. Ship’s company to be informed in this sense….

The men in the destroyers called their old commodore “Achmed Bey.” He was Konteradmiral Bey, who, as senior officer, was in command of the operation because the actual flag officer of the 1st Battle Group, Admiral Kummetz, with his Chief of Staff, was on leave subsequent to the damaging of the Tirpitz. The staff had approved their going quite happily, for it had seemed unthinkable to send the battle cruiser to sea in the deep polar night. But as it was, it turned out otherwise — with the result that this difficult operation was in the charge of an officer who had never commanded a battleship, although he was a well-known destroyer commander.

To begin with, everything went as well as those on board could wish. The convoy — whose official title was J W 55B — was several times sighted and reported by German forces in spite of bad visibility, night, and snowstorms. Long-range reconnaissance aircraft picked it up with their radar, and U-boats were stationed on a wide arc of reconnaissance across which the convoy must pass to reach its objective. Having allowed the convoy to pass, they surfaced and immediately reported its position. From all these reports the staff could get an approximate picture of its course. And Scharnhorst and her five destroyers were steering at high speed toward the estimated point of contact.

In the early-morning hours of the second day Konteradmiral Bey ordered the destroyers to carry out a wide sweep to the northward. At first the Scharnhorst remained astern of them, but then turned onto a northerly course and was soon out of sight. The destroyers never saw the battle cruiser again. Only once afterward, at about nine in the morning, they made out star shells in the sky in the direction in which they believed the ship to be. Was she in action?

According to Chief Petty Officer Godde, one of the survivors, who was standing during the whole action quite close to the conning tower in his action station at the port captain’s sight, it was exactly 8:24 a.m. when he suddenly saw great columns of water through his binoculars.

“Those are shell splashes,” flashed through Godde’s head, “from medium-caliber guns!” He reported at once to the captain on the command telephone line, with which he was connected: “Several splashes, estimated to be 8-inch, 400 to 500 yards on the port side.”

At this moment the first star shell burst into brilliant light through the thick snow squalls, slightly to the side of the German ship. These were being fired from another direction — there must be several enemy ships in the vicinity, probably cruisers, and they had sighted the Scharnhorst without first being picked up by her. In this way they had been able to train their guns quietly on an enemy who could not see them, blind as she was in the darkness of the snowstorm.

“They can only have done that with radar,” thought the German captain, Captain Hintze. Aloud he asked, “No report from the radar set?” The report came through at the same instant, just as the second salvo from the invisible enemy crashed into the water, dangerously close now to the ship. At last the foremost radar set has picked up the enemy. Meanwhile the gun directors have trained onto the enemy’s bright muzzle flashes, firing out of the misty distance — the only point of aim which all their efforts can find. And seconds afterward the first salvo crashes from our own main armament.

But there lingers an unpleasant feeling, most of all among those who realize the importance of this early and accurate radar ranging by the enemy in such conditions of weather, when visibility is practically nil. And this feeling is heightened when, after the 15-minute action which the German battle cruiser breaks off through her high speed, taking advantage of the fog, there is a report concerning the single hit received — it has passed through the foremast. The radar has been hit and is no longer in working order….

“That would happen,” the captain observed, “and in weather like this!”

“All the same, Hintze,” the senior officer replied, “we must make another attempt to get at the convoy. We are now steaming north, and we’ll come in from there. By that time, with luck, we shall have shaken off the cruisers.”

“That’s it — we shall have to rely on the after radar set, although it’s not placed so high and can’t operate ahead.”

The clock in the charthouse of the British battleship Duke of York was showing 03:39 on the morning of December 26 when a flag lieutenant approached Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser where he was sleeping in a chair.

“Signal from Admiralty, sir.”

The Admiral was awake in a moment, and he had scarcely read the few lines of the signal before he had sent for his Chief of Staff.

“Well, I was right,” he began. “The Admiralty has just reported that the Scharnhorst probably went to sea yesterday evening.” The Chief of Staff crossed to the chart on which was indicated the position of all British ships at sea, of the valuable convoy, which was escorted only by destroyers, of the 10th Cruiser Squadron, consisting of the cruisers Belfast, Sheffield, and Norfolk, and lastly of his own battle squadron, consisting of the 35,000-ton Duke of York, the cruiser Jamaica, and four destroyers. A quick glance was sufficient.

“If the Scharnhorst attacks at once and then disappears again we shall not arrive in time, sir.”

“That’s correct. Clearly we shall have to steam east at high speed so as to cut off her retreat.”

“If the cruisers can bring her to action and stop her, we may perhaps do it, sir.”

“There’s one other possibility. The Scharnhorst is certainly making for the convoy. She’ll want to avoid action with our cruisers if she possibly can. So the 10th Cruiser Squadron must remain between her and the convoy so as to keep the Scharnhorst at bay. We shall turn the convoy itself onto a more northerly course so as to draw the Scharnhorst further away from the coast.”

“For that we shall have to break radio silence, sir.”

“Yes, that’s true. The Germans will know we are approaching. But in the long run that is the lesser of the two evils, and it must be accepted. I only hope that once the cruisers have made contact with the Scharnhorst they will be able to form a consecutive picture of her movements with their radar.”

And that was exactly how it happened. Through their radar the English were in a position to shadow the German ship and to attack it when it approached too close to the convoy. In the first engagement of this kind, as we have said, the single radar set on the foremast was destroyed by the only hit she received, other than a shell which did not explode. And again on her attempt to pick up the convoy from the northward while the detached destroyers attacked from the south she came up once again against the cruisers, waiting vigilant as watchdogs.

During this whole period, as the convoy made a skillful detour to the northward, Admiral Fraser, far to the west, pressed on at full speed with his heavy battleship in order to close the pincers around the German ship.

About two hours after the first engagement with the British cruisers a radio message was received in the Scharnhorst from Gruppe Nord. Admiral Bey knitted his brows. An air reconnaissance report referred to a formation of five ships to the west of North Cape. The position given was approximate.

“Well, they can’t be German ships; we would know about them all right,” the Admiral said to Captain Hintze. “It smells to me unpleasantly like an enemy force which we haven’t yet heard about.”

“Five ships — probably one or two battleships with screen, Herr Admiral.”

“I think so too. Well, we can’t do anything for the time being; they are much too far to the westward. There’s nothing for us to do except go for the convoy!”

The OKM[2] had assumed that the aircraft had sighted our five destroyers returning to base. They guessed therefore that Admiral Bey had detached the small ships on account of the storm and heavy sea. For this reason they gave Bey no further instructions, as they would certainly have done in different circumstances. The conduct of the Senior Air Officer in the Northwest had also contributed a good deal to the confusion. In fact the first aircraft report ran as follows:

Five ships probably including a heavy ship sighted northwest of North Cape.

The Senior Air Officer had met the observer concerned with a sharp remark on landing.

“I don’t want to read any ‘probable’ information in reconnaissance reports from here. You are simply to report what you have seen!”

So “probably including a heavy ship” was left out. If it had stayed in the message, the OKM could scarcely have jumped to the conclusion that the message referred to our own destroyers. It would then not have repeated it without comment to the Scharnhorst but would undoubtedly have given an urgent warning about the approaching English battleship.

Well, that did not happen, yet in fact Admiral Bey made a correct evaluation of the situation nevertheless; he knew quite well that the five ships which had been reported could not be his own destroyers, which he had not yet released. But as a result of the approximate position given he considered the danger to be possibly further to the westward than it actually was. There was nothing to do now but to go for the convoy — and by this means he was drawn even further northward and away from the coast. When he finally realized with a heavy heart, after a second engagement with the radar-watchful cruisers, that he would not be able to reach the precious transports in this way, it was too late, and he gave orders to break off action.

In the meantime Admiral Fraser had put his force into the gap, and the pincers were closing. At any moment the radar sets in his flagship the Duke of York might report picking up the Scharnhorst, which was still being held continuously by the radar of the shadowing cruisers. At a time when normal eyes aided by the best binoculars could make out nothing but darkness swept by ghostly snow squalls, the yellowish-green eye of war was controlling this fight as well.

The book by F. O. Busch, The Tragedy of North Cape, taken from Admiral Fraser’s official report and from the accounts of the few German survivors, describes how the Scharnhorst ran into an enemy bent on her destruction, and how she carried the unavoidable fight, herself almost blind against an enemy who could see through his radar, through to the bitter end. Shattered by heavy shells and hit by countless torpedoes the Scharnhorst finally capsized at about 7:00 p.m. on December 26, 1943, to sink a short while afterward into the icy sea. At that moment hundreds of survivors who had got out of the ship in time were still swimming, struggling with all their strength to keep themselves above water, on to life rafts, wooden gratings, anything which would float. But their limbs soon stiffened from the cold and their strength left them. That was how most of them, including the Admiral, the captain, and all the officers, were swallowed up before English help could arrive.

Two British destroyers between them saved 36 German seamen, but over 1,900 went down with their ship.

At this time Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser summoned the officers of his staff and of his flagship, the Duke of York.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “we have sunk the Scharnhorst. This is more than a victorious engagement; it is a strategic success of great importance: the ‘fleet in being’ of our enemy, the threat to our convoy route, has ceased to exist. There will be other tasks for us next year.” The Admiral glanced silently along the line of officers, before raising his voice. “There is one thing more that I should like to say, gentlemen. If you should ever be in the position of having to command a heavy ship against many times superior odds, I hope that you will do as they did, that you will maneuver your ship as well and with your ship’s company will fight as bravely as the officers of the Scharnhorst have done today.”

When the Duke of York sailed next day from Murmansk to England, Admiral Fraser had a large wreath dropped over the side at the position where the Scharnhorst sank. There with his officers and the guard of honor he stood long at the salute, while in final greeting the English wreath sank slowly into the German seamen’s grave.

__________________________________________________

[1] From the preceding chapter: “Hitler himself issued the general order that no scientific research should be embarked on which could not be brought to a conclusive result within a year — a death sentence for any extensive research into new lines of radar technique. The Navy worked on, it is true, but only using a small group of technicians; while in England and America everything was being done to transform the inferiority of their radar technique by comparison with that of the Germans into a decisive superiority.”

[2] Oberkommando der Marine (High Command of the Navy).