Editor’s note: The following article by Jack Barham is extracted from Infantry, Volume 76, Number 1 (January-February 1986). Some of the information is outdated, but the character and basic mission of this force remains unchanged.

Unless you’ve been stationed in Southern Europe, you may not be aware that our NATO ally Italy maintains the largest force of mountain troops in the free world. And unless you’ve had a chance to watch a company of Alpini moving across a mountain snowfield bearing all their weapons and equipment, on all-purpose military skis, and at a pace that leaves the average sport skier with specialized equipment floundering in their wake, you may not know that they are also the best mountain troops in the world.

Unless you are pretty familiar with mountain warfare tactics, you probably don’t know that Italy is the last of the world’s industrialized nations to maintain mule stables in their modern army. Despite many innovations in mountaineering machinery, nobody has found a substitute for getting heavy and medium mortars into places the Alpini like to shoot mortars from, which is to say the peaks of alpine mountains accessible only to mules, mountain goats, and Alpini soldiers. (They also use helicopters and an ingenious tracked, mechanized sled called an “Alpini scooter,” but nothing can move through a cloud over a treacherous mountain trail so well as an Alpini mule.)

Italy borders France, Switzerland, Austria, and Yugoslavia. Any force invading Italy by land would have to pass over mountains. Internally, the land mass of Italy ranges from mountainous to hilly, with very little really flat terrain. So it makes sense for the Italians to maintain a fairly large body of mountain troops, and to make sure that these troops are very good at what they do.

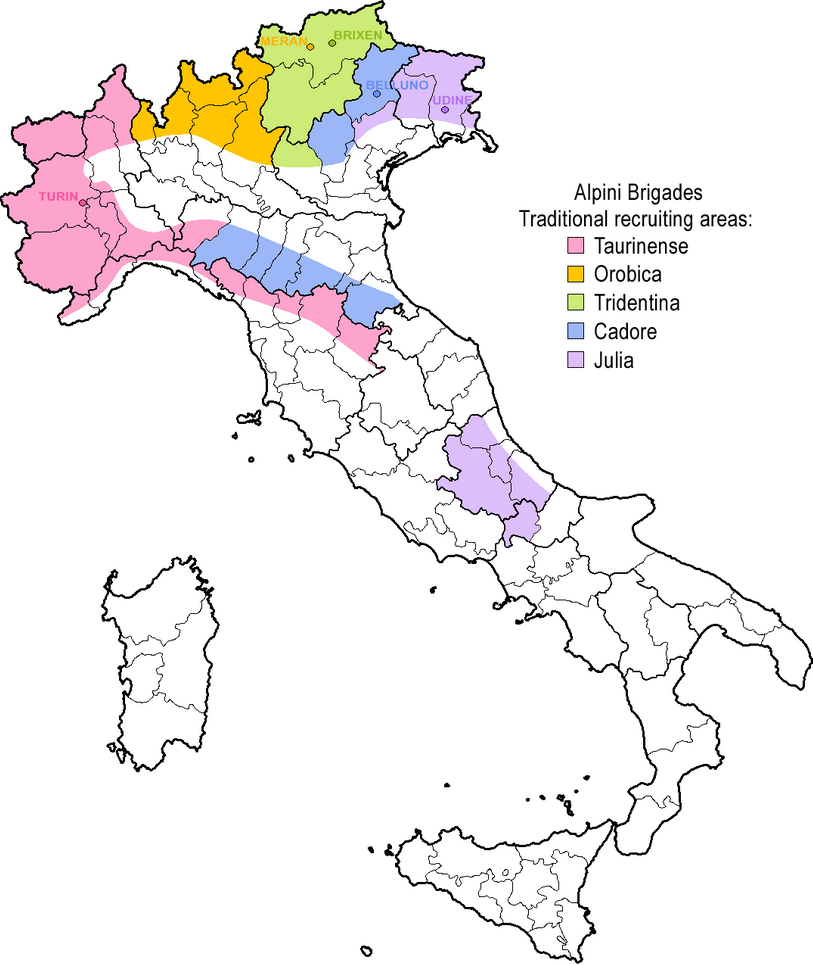

Thus the Italian Army 4th Corps (Alpini), which presently consists of five brigades, is simply a necessary military force, fitted and trained for its mission. It is, in fact, a well fitted and superbly trained military organization.

Each brigade is composed of three or four battalions of mountain infantry, a battalion of mountain artillery, with varying numbers of mountain engineers, signalers, and logisticians.

There is even a battalion of Alpini paratroopers who go looking for drop zones that sane jumpers have nightmares about.

The most impressive demonstration of mountain warfare skills ever observed by the writer occurred at a couple of renditions of CaSTA. That’s the Italian acronym for Campionati sciistici della Truppe Alpini or Alpini Ski Championships. Each year the brigades send their best military skiers to a designated location in the Italian Alps to compete in the kind of skiing Alpini do — that is, tactical, cross-country, all-terrain, full load bearing. Most of the events are squad and platoon level races of varying distance over terrain that would tear a snowmobile apart.

Tactical units (squads and platoons must be honest — no ringers) race against time and each other and fire their weapons against still and moving targets along the way. In some events the unit cannot continue the race until all of its targets have been hit. In others a distance penalty is assessed for every miss. To win a CaSTA event is, in peacetime, the greatest possible achievement for an Alpini squad or platoon leader.

Being able to do that kind of skiing with one’s company builds a good measure of esprit de corps, but the Alpini professionals build on these activities to instill in each of their soldiers a tremendous unit loyalty that endures long after his active duty days are past.

They start with a young conscript who has about the same attitude toward military service that young Americans did back in the days when they, too, were being drafted. But the Italian draftee has expected it from the day he became aware that he was a healthy male and that Italy maintained armed forces. He knows he’s going to spend a year on active duty. (Or eighteen months if he wants to specialize as a medic, an engineer, or a radio operator, or to accept basic NCO rank.) And he knows that every other young Italian man will spend the same amount of time on active duty. While deferments are easy to acquire, sooner or later everybody serves. Exceptions are almost non-existent.

(The Italian Government does a lot for its armed services in this respect. All able-bodied men serve, but each can choose his time. If he wants to complete college, fine. Get married, sure. Have six kids, his choice. But sooner or later he’s going to do his year to 18 months in the armed forces. So the Italian conscript reports to his first duty assignment without the sense of injustice that often plagued the U.S. selective service system.)

He is an Alpino by choice. If he wants to be a tanker or a leg infantryman or a regular paratrooper instead or join the Italian Navy or Air Force, he has those options. If he’s a mountain boy though, he almost always picks the Alpini, for that means he’ll be stationed close to home. It means he’ll spend a lot of time on skis, something he probably already knows something about and likes to do. When his tour of active duty is over, he will take his distinctive Alpini hat and return to his home town, an acknowledged veteran of tough training, and join his father and grandfather in the local chapter of the highly respected Alpini Veterans’ Association.

The Alpini private spends his first six to eight weeks of active duty at Aosta, the Alpini equivalent of Fort Benning, where he learns to fire his rifle (NATO 7.62mm FAL), move in the mountains, and accept the stern discipline of the Alpini Corps.

The training is tough. And “realistic” is an understatement. When a 19-year old finds himself hanging from a nylon rope 400 feet above the rocks, and when what’s holding that rope is a fellow trainee, mutual respect develops quickly. When his fellow trainee doesn’t drop him because their sergeant has shown them how to safely conduct a belay, that respect extends to the NCOs. And when the trainee sees the respect the NCOs give to the officers, he starts to learn something about military discipline. Soon he begins to feel pretty good about being a member of his squad, platoon, and company, even if he doesn’t especially like hanging 400 feet over the rocks.

After his basic training, the new Alpino joins his unit. With rare exception he will spend his entire active duty period with the same squad. And although he will serve only a year, almost every day of that year will be filled with intensive unit training. Each soldier gets 10 days of leave during his first year of active duty. The remainder of the time he trains six days a week. His training incorporates everything an Alpino needs to know, from digging snow caves to learning the unit songs. (If he plays an instrument especially well, or has an extraordinary singing voice, he may be accepted into the brigade band or chorus, an option many conscripts prefer to digging snow caves or hanging over rocks. Regardless, every Alpino can sing his unit songs.)

The officers are almost all career men, graduates of the Italian Military Academy and the Alpini Officers’ Course at Aosta, where new lieutenants spend six months cruising deep powder and hand-carrying 81mm mortars up mountain peaks. (It teaches the lieutenants to appreciate the mules.) Their mission is to train their men so well that a youth who spends his year on active duty can be recalled years later, should the nation mobilize for war, with most of his mountain skills intact. The training is almost exclusively mountain oriented, and it truly builds men who know what to do in the mountains.

Their equipment is first class. The FAL rifle (usually issued with folding stock) is a little heavy for carrying up a rope, but the Italians like its range and accuracy. Their skis, climbing gear, and other items necessary to mountain survival are the best that can be produced in Italy or purchased elsewhere. Even the uniforms of the private soldiers are of high quality material, well designed and carefully tailored for each man.

The dominant item of the uniform is the hat, alpine style, with a distinctive black feather (white for field grade officers and above). It is the most respected headgear in the Italian armed forces. Each soldier takes the hat with him when he leaves active duty, wears it to meetings of the Alpini Veterans’ Association, and honors it for the rest of his life.

The Alpini’s proudest days were in World War I, when they beat the mighty Austro-Hungarian Army, took the Upper Adige (now much of northern Italy), and, at terrible cost, reclaimed Trieste. They make no excuses for backing a loser in World War II, but stress the valor of the Alpini units, which the Germans used to cover their retreats in the mountains of Greece, Russia, and Italy. And they are quick to mention that the Alpini were the first members of the Italian Army to form a volunteer battalion and fight the Germans alongside U.S. forces in Italy.

Alpini units are deployed throughout northern Italy, with most of the combat units distributed in the northeast. Their active duty strength is under 10,000, but in every city, town, and village in northern Italy are mountain men who have Alpini hats on their mantles and the skills of mountain soldiers in their bodies. They have standing assignments, usually to their old units, and if the need should ever arise, they will be ready, willing, and very able to swell the Alpini force to a formidable size on short notice. Skilled, professional, determined, these “men in high places” are indeed a force to be reckoned with.

_________________________________

Jack Barham, a retired Army lieutenant colonel, was Editor of INFANTRY magazine from 1974 to 1979. He then went on to serve as Public Affairs Officer of the Southeast European Task Force in Italy and remained in Italy after his retirement. He served in Vietnam with the 25th Infantry Division.

5

4