Editor’s Note: The following comprises the sixteenth chapter of The Holy Roman Empire, by James Bryce (published 1871). All spelling in the original.

(Continued from Part 15)

CHAPTER XVI

THE CITY OF ROME IN THE MIDDLE AGES

‘It is related,’ says Sozomen in the ninth book of his Ecclesiastical History, ‘that when Alaric was hastening against Rome, a holy monk of Italy admonished him to spare the city, and not to make himself the cause of such fearful ills. But Alaric answered, “It is not of my own will that I do this; there is One who forces me on, and will not let me rest, bidding me spoil Rome.”‘

Towards the close of the tenth century the Bohemian Woitech, famous in after legend as St. Adalbert, forsook his bishopric of Prague to journey into Italy, and settled himself in the Roman monastery of Sant’ Alessio. After some few years passed there in religious solitude, he was summoned back to resume the duties of his see, and laboured for awhile among his half-savage countrymen. Soon, however, the old longing came over him: he resought his cell upon the brow of the Aventine, and there, wandering among the ancient shrines, and taking on himself the menial offices of the convent, he abode happily for a space. At length the reproaches of his metropolitan, the archbishop of Mentz, and the express commands of Pope Gregory the Fifth, drove him back over the Alps, and he set off in the train of Otto the Third, lamenting, says his biographer, that he should no more enjoy his beloved quiet in the mother of martyrs, the home of the Apostles, golden Rome. A few months later he died a martyr among the pagan Lithuanians of the Baltic.

Nearly four hundred years later, and nine hundred after the time of Alaric, Francis Petrarch writes thus to his friend John Colonna:—

‘Thinkest thou not that I long to see that city to which there has never been any like nor ever shall be; which even an enemy called a city of kings; of whose people it hath been written, “Great is the valour of the Roman people, great and terrible their name;” concerning whose unexampled glory and incomparable empire, which was, and is, and is to be, divine prophets have sung; where are the tombs of the apostles and martyrs and the bodies of so many thousands of the saints of Christ?’

It was the same irresistible impulse that drew the warrior, the monk, and the scholar towards the mystical city which was to mediæval Europe more than Delphi had been to the Greek or Mecca to the Islamite, the Jerusalem of Christianity, the city which had once ruled the earth, and now ruled the world of disembodied spirits. For there was then, as there is now, something in Rome to attract men of every class. The devout pilgrim came to pray at the shrine of the Prince of the Apostles, too happy if he could carry back to his monastery in the forests of Saxony or by the bleak Atlantic shore the bone of some holy martyr; the lover of learning and poetry dreamed of Virgil and Cicero among the shattered columns of the Forum; the Germanic kings, in spite of pestilence, treachery and seditions, came with their hosts to seek in the ancient capital of the world the fountain of temporal dominion. Nor has the spell yet wholly lost its power. To half the Christian nations Rome is the metropolis of religion, to all the metropolis of art. In her streets, and hers alone among the cities of the world, may every form of human speech be heard: she is more glorious in her decay and desolation than the stateliest seats of modern power.

But while men thought thus of Rome, what was Rome herself?

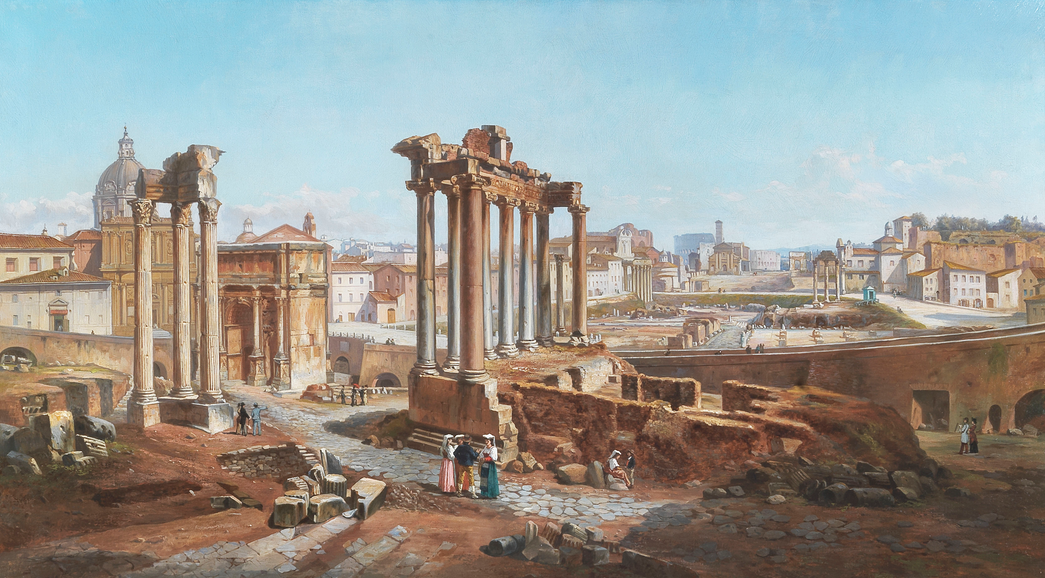

The modern traveller, after his first few days in Rome, when he has looked out upon the Campagna from the summit of St. Peter’s, paced the chilly corridors of the Vatican, and mused under the echoing dome of the Pantheon, when he has passed in review the monuments of regal and republican and papal Rome, begins to seek for some relics of the twelve hundred years that lie between Constantine and Pope Julius the Second. ‘Where,’ he asks, ‘is the Rome of the Middle Ages, the Rome of Alberic and Hildebrand and Rienzi? the Rome which dug the graves of so many Teutonic hosts; whither the pilgrims flocked; whence came the commands at which kings bowed? Where are the memorials of the brightest age of Christian architecture, the age which reared Cologne and Rheims and Westminster, which gave to Italy the cathedrals of Tuscany and the wave-washed palaces of Venice?’

To this question there is no answer. Rome, the mother of the arts, has scarcely a building to commemorate those times, for to her they were times of turmoil and misery, times in which the shame of the present was embittered by recollections of a brighter past. Nevertheless a minute scrutiny may still discover, hidden in dark corners or disguised under an unbecoming modern dress, much that carries us back to the mediæval town, and helps us to realize its social and political condition. Therefore a brief notice of the state of Rome during the Middle Ages, with especial reference to those monuments which the visitor may still examine for himself, may not be without its use, and is at any rate no unfitting pendant to an account of the institution which drew from the city its name and its magnificent pretensions. Moreover, as will appear more fully in the sequel, the history of the Roman people is an instructive illustration of the influence of those ideas upon which the Empire itself rested, as well in their weakness as in their strength.

Causes of the rapid decay of the city

It is not from her capture by Alaric, nor even from the more destructive ravages of the Vandal Genseric, that the material and social ruin of Rome must be dated, but rather from the repeated sieges which she sustained in the war of Belisarius with the Ostrogoths. This struggle however, long and exhausting as it was, would not have proved so fatal had the previous condition of the city been sound and healthy. Her wealth and population in the middle of the fifth century were probably little inferior to what they had been in the most prosperous days of the imperial government. But this wealth was entirely gathered into the hands of a small and effeminate aristocracy. The crowd that filled her streets was composed partly of poor and idle freemen, unaccustomed to arms and debarred from political rights; partly of a far more numerous herd of slaves, gathered from all parts of the world, and morally even lower than their masters. There was no middle class, and no system of municipal institutions, for although the senate and consuls with many of the lesser magistracies continued to exist, they had for centuries enjoyed no effective power, and were nowise fitted to lead and rule the people. Hence it was that when the Gothic war and the subsequent inroads of the Lombards had reduced the great families to beggary, the framework of society dissolved and could not be replaced. In a state rotten to the core there was no vital force left for reconstruction. The old forms of political activity had been too long dead to be recalled to life: the people wanted the moral force to produce new ones, and all the authority that could be said to exist in the midst of anarchy tended to centre itself in the chief of the new religious society.

Peculiarities in the position of Rome

So far Rome’s condition was like that of the other great towns of Italy and Gaul. But in two points her case differed from theirs, and to these the difference of her after fortunes may be traced. Her bishop had no temporal potentate to overshadow his dignity or check his ambition, for the vicar of the Eastern court lived far away at Ravenna, and seldom interfered except to ratify a papal election or punish a more than commonly outrageous sedition. Her population received an all but imperceptible infusion of that Teutonic blood and those Teutonic customs by whose stern discipline the inhabitants of northern Italy were in the end renovated. Everywhere the old institutions had perished of decay: in Rome alone there was nothing except the ecclesiastical system out of which new ones could arise. Her condition was therefore the most pitiable in which a community can find itself, one of struggle without purpose or progress. The citizens were divided into three orders: the military class, including what was left of the ancient aristocracy; the clergy, a host of priests, monks and nuns, attached to the countless churches and convents; and the people or plebs, as they are called, a poverty-stricken rabble without trade, without industry, without any municipal organization to bind them together. Of these two latter classes the Pope was the natural leader, the first was divided into factions headed by some three or four of the great families, whose quarrels kept the town in incessant bloodshed. The internal history of Rome from the sixth to the twelfth century is an obscure and tedious record of the contest of these factions with each other, and of the aristocracy as a whole with the slowly growing power of the Church.

Her condition in the ninth and tenth centuries

The revolt of the Romans from the Iconoclastic Emperors of the East, followed as it was by the reception of the Franks as patricians and emperors, is an event of the highest importance in the history of Italy and of the popedom. In the domestic constitution of Rome it made little change. With the instinct of a profound genius, Charles the Great saw that Rome, though it might be ostensibly the capital, could not be the real centre of his dominions. He continued to reside in Germany, and did not even build a palace at Rome. For a time the awe of his power, the presence of his missus or lieutenant, and the occasional visits of his successors Lothar and Lewis II to the city, repressed her internal disorders. But after the death of the prince last named, and still more after the dissolution of the Carolingian Empire itself, Rome relapsed into a state of profligacy and barbarism to which, even in that age, Europe supplied no parallel, a barbarism which had inherited all the vices of civilization without any of its virtues. The papal office in particular seems to have lost its religious character, as it had certainly lost all claim to moral purity. For more than a century the chief priest of Christendom was no more than a tool of some ferocious faction among the nobles. Criminal means had raised him to the throne; violence, sometimes going the length of mutilation or murder, deprived him of it. The marvel is, a marvel in which papal historians have not unnaturally discovered a miracle, that after sinking so low, the Papacy should ever have risen again. Its rescue and exaltation to the pinnacle of glory was accomplished not by the Romans but by the efforts of the Transalpine Church, aiding and prompting the Saxon and Franconian Emperors. Yet even the religious reform did not abate intestine turmoil, and it was not till the twelfth century that a new spirit began to work in politics, which ennobled if it could not heal the sufferings of the Roman people.

Growth of a republican feeling: hostility to the Popes

Ever since the time of Alberic their pride had revolted against the haughty behaviour of the Teutonic emperors. From still earlier times they had been jealous of sacerdotal authority, and now watched with alarm the rapid extension of its influence. The events of the twelfth century gave these feelings a definite direction. It was the time of the struggle of the Investitures, in which Hildebrand and his disciples had been striving to draw all the things of this world as well as of the next into their grasp. It was the era of the revived study of Roman law, by which alone the extravagant pretensions of the decretalists could be resisted. The Lombard and Tuscan towns had become flourishing municipalities, independent of their bishops, and at open war with their Emperor.

Arnold of Brescia

While all these things were stirring the minds of the Romans, Arnold of Brescia came preaching reform, denouncing the corrupt life of the clergy, not perhaps, like some others of the so-called schismatics of his time, denying the need of a sacerdotal order, but at any rate urging its restriction to purely spiritual duties. On the minds of the Romans such teaching fell like the spark upon dry grass; they threw off the yoke of the Pope, drove out the imperial prefect, reconstituted the senate and the equestrian order, appointed consuls, struck their own coins, and professed to treat the German Emperors as their nominees and dependants. To have successfully imitated the republican constitution of the cities of northern Italy would have been much, but with this they were not content. Knowing in a vague ignorant way that there had been a Roman republic before there was a Roman empire, they fed their vanity with visions of a renewal of all their ancient forms, and saw in fancy their senate and people sitting again upon the Seven Hills and ruling over the kings of the earth. Stepping, as it were, into the arena where Pope and Emperor were contending for the headship of the world, they rejected the one as a priest, and declaring the other to be only their creature, they claimed as theirs the true and lawful inheritance of the world-dominion which their ancestors had won. Antiquity was in one sense on their side, and to us now it seems less strange that the Roman people should aspire to rule the earth than that a German barbarian should rule it in their name. But practically the scheme was absurd, and could not maintain itself against any serious opposition. As a modern historian aptly expresses it, ‘they were setting up ruins:’ they might as well have raised the broken columns that strewed their Forum and hoped to rear out of them a strong and stately temple. The reverence which the men of the Middle Ages felt for Rome was given altogether to the name and to the place, nowise to the people. As for power, they had none: so far from holding Italy in subjection, they could scarcely maintain themselves against the hostility of Tusculum.

Short-sighted policy of the Emperors

But it would have been well worth the while of the Teutonic Emperors to have made the Romans their allies, and bridled by their help the temporal ambition of the Popes. The offer was actually made to them, first to Conrad the Third, who seems to have taken no notice of it; and afterwards, as has been already stated, to Frederick the First, who repelled in the most contumelious fashion the envoys of the senate. Hating and fearing the Pope, he always respected him: towards the Romans he felt all the contempt of a feudal king for burghers, and of a German warrior for Italians. At the demand of Pope Hadrian, whose foresight thought no heresy so dangerous as one which threatened the authority of the clergy, Arnold of Brescia was seized by the imperial prefect, put to death, and his ashes cast into the Tiber, lest the people should treasure them up as relics. But the martyrdom of their leader did not quench the hopes of his followers. The republican constitution continued to exist, and rose from time to time, during the weakness or the absence of the Popes, into a brief and fitful activity. Once awakened, the idea, seductive at once to the imagination of the scholar and the vanity of the Roman citizen, could not wholly disappear, and two centuries after Arnold’s time it found a more brilliant if less disinterested exponent in the tribune Nicholas Rienzi.

Character and career of the tribune Rienzi

The career of this singular personage is misunderstood by those who suppose him to have been possessed of profound political insight, a republican on modern principles. He was indeed, despite his overweening conceit, and what seems to us his charlatanry, both a patriot and a man of genius, in temperament a poet, filled with soaring ideas. But those ideas, although dressed out in gaudier colours by his lively fancy, were after all only the old ones, memories of the long-faded glories of the heathen republic, and a series of scornful contrasts levelled at her present oppressors, both of them shewing no vista of future peace except through the revival of those ancient names to which there were no things to correspond. It was by declaiming on old texts and displaying old monuments that the tribune enlisted the support of the Roman populace, not by any appeal to democratic principles; and the whole of his acts and plans, though they astonished men by their boldness, do not seem to have been regarded as novel or impracticable. In the breasts of men like Petrarch, who loved Rome even more than they hated her people, the enthusiasm of Rienzi found a sympathetic echo: others scorned and denounced him as an upstart, a demagogue, and a rebel. Both friends and enemies seem to have comprehended and regarded as natural his feelings and designs, which were altogether those of his age. Being, however, a mere matter of imagination, not of reason, having no anchor, so to speak, in realities, no true relation to the world as it then stood, these schemes of republican revival were as transient and unstable as they were quick of growth and gay of colour. As the authority of the Popes became consolidated, and free municipalities disappeared elsewhere throughout Italy, the dream of a renovated Rome at length withered up and fell and died. Its last struggle was made in the conspiracy of Stephen Porcaro, in the time of Pope Nicholas the Fifth; and from that time onward there was no question of the supremacy of the bishop within his holy city.

Causes of the failure of the struggle for independence

It is never without a certain regret that we watch the disappearance of a belief, however illusive, around which the love and reverence for mankind once clung. But this illusion need be the less regretted that it had only the feeblest influence for good on the state of mediæval Rome. During the three centuries that lie between Arnold of Brescia and Porcaro, the disorders of Rome were hardly less violent than they had been in the Dark Ages, and to all appearance worse than those of any other European city. There was a want not only of fixed authority, but of those elements of social stability which the other cities of Italy possessed. In the greater republics of Lombardy and Tuscany the bulk of the population were artizans, hard working orderly people; while above them stood a prosperous middle class, engaged mostly in commerce, and having in their system of trade-guilds an organization both firm and flexible. It was by foreign trade that Genoa, Venice, and Pisa became great, as it was the wealth acquired by manufacturing industry that enabled Milan and Florence to overcome and incorporate the territorial aristocracies which surrounded them.

Internal condition of the city

The people

Rome possessed neither source of riches. She was ill-placed for trade; having no market she produced no goods to be disposed of, and the unhealthiness which long neglect had brought upon her Campagna made its fertility unavailable. Already she stood as she stands now, lonely and isolated, a desert at her very gates. As there was no industry, so there was nothing that deserved to be called a citizen class. The people were a mere rabble, prompt to follow the demagogue who flattered their vanity, prompter still to desert him in the hour of danger. Superstition was with them a matter of national pride, but they lived too near sacred things to feel much reverence for them: they ill-treated the Pope and fleeced the pilgrims who crowded to their shrines: they were probably the only community in Europe who sent no recruit to the armies of the Cross. Priests, monks, and all the nondescript hangers on of an ecclesiastical court formed a large part of the population; while of the rest many were supported in a state of half mendicancy by the countless religious foundations, themselves enriched by the gifts or the plunder of Latin Christendom.

The nobility

The noble families were numerous, powerful, ferocious; they were surrounded by bands of unruly retainers, and waged a constant war against each other from their castles in the adjoining country or in the streets of the city itself. Had things been left to take their natural course, one of these families, the Colonna, for instance, or the Orsini, would probably have ended by overcoming its rivals, and have established, as was the case in the republics of Romagna and Tuscany, a ‘signoria’ or local tyranny, like those which had once prevailed in the cities of Greece.

The bishop

But the presence of the sacerdotal power, as it had hindered the growth of feudalism, so also it stood in the way of such a development as this, and in so far aggravated the confusion of the city. Although the Pope was not as yet recognized as legitimate sovereign, he was not only the most considerable person in Rome, but the only one whose authority had anything of an official character. But the reign of each pontiff was short; he had no military force, he was frequently absent from his see. He was, moreover, very often a member of one of the great families, and, as such, no better than a faction leader at home, while venerated by the rest of Europe as the universal priest.

The Emperor

It remains only to speak of the person who should have been to Rome what the national king was to the cities of France, or England, or Germany, that is to say, of the Emperor. As has been said already, his power was a mere chimera, chiefly important as furnishing a pretext to the Colonna and other Ghibeline chieftains for their opposition to the papal party. Even his abstract rights were matter of controversy. The Popes, whose predecessors had been content to govern as the lieutenants of Charles and Otto, now maintained that Rome as a spiritual city could not be subject to any temporal jurisdiction, and that she was therefore no part of the Roman Empire, though at the same time its capital. Not only, it was urged, had Constantine yielded up Rome to Sylvester and his successors, Lothar the Saxon had at his coronation formally renounced his sovereignty by doing homage to the pontiff and receiving the crown as his vassal. The Popes felt then as they feel now, that their dignity and influence would suffer if they should even appear to admit in their place of residence the jurisdiction of a civil potentate, and although they could not secure their own authority, they were at least able to exclude any other.

Visits of the Emperors to Rome

Hence it was that they were so uneasy whenever an Emperor came to them to be crowned, that they raised up difficulties in his path, and endeavoured to be rid of him as soon as possible. And here something must be said of the programme, as one may call it, of these imperial visits to Rome, and of the marks of their presence which the Germans left behind them, remembering always that after the time of Frederick the Second it was rather the exception than the rule for an Emperor to be crowned in his capital at all.

Their approach

The traveller who enters Rome now, if he comes, as he most commonly does, by way of Civita Vecchia, slips in by the railway before he is aware, is huddled into a vehicle at the terminus, and set down at his hotel in the middle of the modern town before he has seen anything at all. If he comes overland from Tuscany along the bleak road that passes near Veii and crosses the Milvian bridge, he has indeed from the slopes of the Ciminian range a splendid prospect of the sea-like Campagna, girdled in by glittering hills, but of the city he sees no sign, save the pinnacle of St. Peter’s, until he is within the walls. Far otherwise was it in the Middle Ages. Then travellers of every grade, from the humble pilgrim to the new-made archbishop who came in the pomp of a lengthy train to receive from the Pope the pallium of his office, approached from the north or north-east side; following a track along the hilly ground on the Tuscan side of the Tiber until they halted on the brow of Monte Mario —the Mount of Joy—and saw the city of their solemnities lie spread before them, from the great pile of the Lateran far away upon the Cœlian hill, to the basilica of St. Peter’s at their feet. They saw it not, as now, a sea of billowy cupolas, but a mass of low red-roofed houses, varied by tall brick towers, and at rarer intervals by masses of ancient ruin, then larger far than now; while over all rose those two monuments of the best of the heathen Emperors, monuments that still look down, serenely changeless, on the armies of new nations and the festivals of a new religion—the columns of Marcus Aurelius and Trajan.

Their entrance

From Monte Mario the Teutonic host descended, when they had paid their orisons, into the Neronian field, the piece of flat land that lies outside the gate of St. Angelo. Here it was the custom for the elders of the Romans to meet the elected Emperor, present their charters for confirmation, and receive his oath to preserve their good customs. Then a procession was formed: the priests and monks, who had come out with hymns to greet the Emperor, led the way; the knights and soldiers of Rome, such as they were, came next; then the monarch, followed by a long array of Transalpine chivalry. Passing into the city they advanced to St. Peter’s, where the Pope, surrounded by his clergy, stood on the great staircase of the basilica to welcome and bless the Roman king. On the next day came the coronation, with ceremonies too elaborate for description, ceremonies which, we may well believe, were seldom duly completed. Far more usual were other rites, of which the book of ritual makes no mention, unless they are to be counted among the ‘good customs of the Romans;’ the clang of war bells, the battle cry of German and Italian combatants. The Pope, when he could not keep the Emperor from entering Rome, required him to leave the bulk of his host without the walls, and if foiled in this, sought his safety in raising up plots and seditions against his too powerful friend.

Hostility of Pope and people to the Germans

The Roman people, on the other hand, violent as they often were against the Pope, felt nevertheless a sort of national pride in him. Very different were their feelings towards the Teutonic chieftain, who came from a far land to receive in their city, yet without thanking them for it, the ensign of a power which the prowess of their forefathers had won. Despoiled of their ancient right to choose the universal bishop, they clung all the more desperately to the belief that it was they who chose the universal prince; and were mortified afresh when each successive sovereign contemptuously scouted their claims, and paraded before their eyes his rude barbarian cavalry. Thus it was that a Roman sedition was the all but invariable accompaniment of a Roman coronation. The three revolts against Otto the Great have been already described. His grandson Otto the Third, in spite of his passionate fondness for the city, was met by the same faithlessness and hatred, and departed at last in despair at the failure of his attempts at conciliation. A century afterwards Henry the Fifth’s coronation produced violent tumults, which ended in his seizing the Pope and cardinals in St. Peter’s, and keeping them prisoners till they submitted to his terms. Remembering this, Pope Hadrian the Fourth would fain have forced the troops of Frederick Barbarossa to remain without the walls, but the rapidity of their movements disconcerted his plans and anticipated the resistance of the Roman populace. Having established himself in the Leonine city, Frederick barricaded the bridge over the Tiber, and was duly crowned in St. Peter’s. But the rite was scarcely finished when the Romans, who had assembled in arms on the Capitol, dashed over the bridge, fell upon the Germans, and were with difficulty repulsed by the personal efforts of Frederick. Into the city he did not venture to pursue them, nor was he at any period of his reign able to make himself master of the whole of it. Finding themselves similarly baffled, his successors at last accepted their position, and were content to take the crown on the Pope’s conditions and depart without further question.

Memorials of the Germanic Emperors in Rome

Coming so seldom and remaining for so short a time, it is not wonderful that the Teutonic Emperors should, in the seven centuries from Charles the Great to Charles the Fifth, have left fewer marks of their presence in Rome than Titus or Hadrian alone have done; fewer and less considerable even than those which tradition attributes to those whom it calls Servius Tullius and the elder Tarquin. Those monuments which do exist are just sufficient to make the absence of all others more conspicuous.

Of Otto the Third

The most important dates from the time of Otto the Third, the only Emperor who attempted to make Rome his permanent residence. Of the palace, probably nothing more than a tower, which he built on the Aventine, no trace has been discovered; but the church, founded by him to receive the ashes of his friend the martyred St. Adalbert, may still be seen upon the island in the Tiber. Having received from Benevento relics supposed to be those of Bartholomew the Apostle, it became dedicated to that saint, and is now the church of San Bartolommeo in Isola, whose quaintly picturesque bell-tower of red brick, now grey with extreme age, looks out from among the orange trees of a convent garden over the swift-eddying yellow waters of the Tiber.

Of Otto the Second

Otto the Second, son of Otto the Great, died at Rome, and lies buried in the crypt of St. Peter’s, the only Emperor who has found a resting-place among the graves of the Popes. His tomb is not far from that of his nephew Pope Gregory the Fifth: it is a plain one of roughly chiselled marble. The lid of the superb porphyry sarcophagus in which he lay for a time now serves as the great font of St. Peter’s, and may be seen in the baptismal chapel, on the left of the entrance of the church, not far from the tombs of the Stuarts.

Of Frederick the Second

Last of all must be mentioned a curious relic of the Emperor Frederick the Second, the prince whom of all others one would least expect to see honoured in the city of his foes. It is an inscription in the palace of the Conservators upon the Capitoline hill, built into the wall of the great staircase, and relates the victory of Frederick’s army over the Milanese, and the capture of the carroccio of the rebel city, which he sends as a trophy to his faithful Romans. These are all or nearly all the traces of her Teutonic lords that Rome has preserved till now. Pictures indeed there are in abundance, from the mosaic of the Scala Santa at the Lateran and the curious frescoes in the church of Santi Quattro Incoronati, down to the paintings of the Sistine antechapel and the Stanze of Raphael in the Vatican, where the triumphs of the Popedom over all its foes are set forth with matchless art and equally matchless unveracity. But these are mostly long subsequent to the events they describe, and these all the world knows.

Associations of the highest interest would have attached to the churches in which the imperial coronation was performed—a ceremony which, whether we regard the dignity of the performers or the splendour of the adjuncts, was probably the most imposing that modern Europe has known. But old St. Peter’s disappeared in the end of the fifteenth century, not long after the last Roman coronation, that of Frederick the Third, while the basilica of St. John Lateran, in which Lothar the Saxon and Henry the Seventh were crowned, has been so woefully modernized that we can hardly figure it to ourselves as the same building.

Causes of the want of mediæval monuments in Rome

Bearing in mind what was the social condition of Rome during the middle ages, it becomes easier to understand the architectural barrenness which at first excites the visitor’s surprise. Rome had no temporal sovereign, and there were therefore only two classes who could build at all, the nobles and the clergy.

Barbarism of the aristocracy

Of these, the former had seldom the wealth, and never the taste, which would have enabled them to construct palaces graceful as the Venetian or massively grand as the Florentine and Genoese. Moreover, the constant practice of domestic war made defence the first object of a house, beauty and convenience the second. The nobility, therefore, either adapted ancient edifices to their purpose or built out of their materials those huge square towers of brick, a few of which still frown over the narrow streets in the older parts of Rome. We may judge of their number from the statement that the senator Brancaleone destroyed one hundred and forty of them. With perhaps no more than one exception, that of the so-called House of Rienzi, these towers are the only domestic buildings in the city older than the middle of the fifteenth century. The vast palaces to which strangers now flock for the sake of the picture galleries they contain, have been most of them erected in the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries, some even later. Among the earliest is that Palazzo Cenci, whose gloomy low-browed arch so powerfully affected the imagination of Shelley.

Ambition, weakness, and corruption of the clergy

It was no want of wealth that hampered the architectural efforts of the clergy, for vast revenues flowed in upon them from every corner of Christendom. A good deal was actually spent upon the erection or repairs of churches and convents, although with a less liberal hand than that of such great Transalpine prelates as Hugh of Lincoln or Conrad of Cologne. But the Popes always needed money for their projects of ambition, and in times when disorder or corruption were at their height the work of building stopped altogether. Thus it was that after the time of the Carolingians scarcely a church was erected until the beginning of the twelfth century, when the reforms of Hildebrand had breathed new zeal into the priesthood. The Babylonish captivity of Avignon, as it was called, with the great schism of the West that followed upon it, was the cause of a second similar intermission, which lasted nearly a century and a half.

Tendency of the Roman builders to adhere to the ancient manner

At every time, however, even when his work went on most briskly, the labours of the Roman architect took the direction of restoring and readorning old churches rather than of erecting new ones. While the Transalpine countries, except in a few favoured spots, such as Provence and part of the Rhineland, remained during several ages with few and rudely built stone churches, Rome possessed, as the inheritance of the earlier Christian centuries, a profusion of houses of worship, some of them still unsurpassed in splendour, and far more than adequate to the needs of her diminished population. In repairing these from time to time, their original form and style of work were usually as far as possible preserved, while in constructing new ones, the abundance of models beautiful in themselves and hallowed as well by antiquity as by religious feeling, enthralled the invention of the workman, bound him down to be at best a faithful imitator, and forbade him to deviate at pleasure from the old established manner. Thus it befel that while his brethren throughout the rest of Europe were passing by successive steps from the old Roman and Byzantine styles to Romanesque, and from Romanesque to Gothic, the Roman architect scarcely departed from the plan and arrangements of the primitive basilica.

Absence of Gothic in Rome

This is one chief reason why there is so little of Gothic work in Rome, so little even of Romanesque like that of Pisa. What there is appears chiefly in the pointed window, more rarely in the arch, seldom or never in spire or tower or column. Only one of the existing churches of Rome is Gothic throughout, and that, the Dominican church of S. Maria sopra Minerva, was built by foreign monks. In some of the other churches, and especially in the cloisters of the convents, instances may be observed of the same style: in others slight traces, by accident or design almost obliterated.

Destruction and alteration of the old buildings:

The mention of obliteration suggests a third cause of the comparative want of mediæval buildings in the city—the constant depredations and changes of which she has been the subject.

By invaders

Ever since the time of Constantine Rome has been a city of destruction, and Christians have vied with pagans, citizens with enemies, in urging on the fatal work. Her siege and capture by Robert Guiscard, the ally of Hildebrand against Henry the Fourth, was far more ruinous than the attacks of the Goths or Vandals: and itself yields in atrocity to the sack of Rome in A.D. 1526 by the soldiers of the Catholic king and most pious Emperor Charles the Fifth.

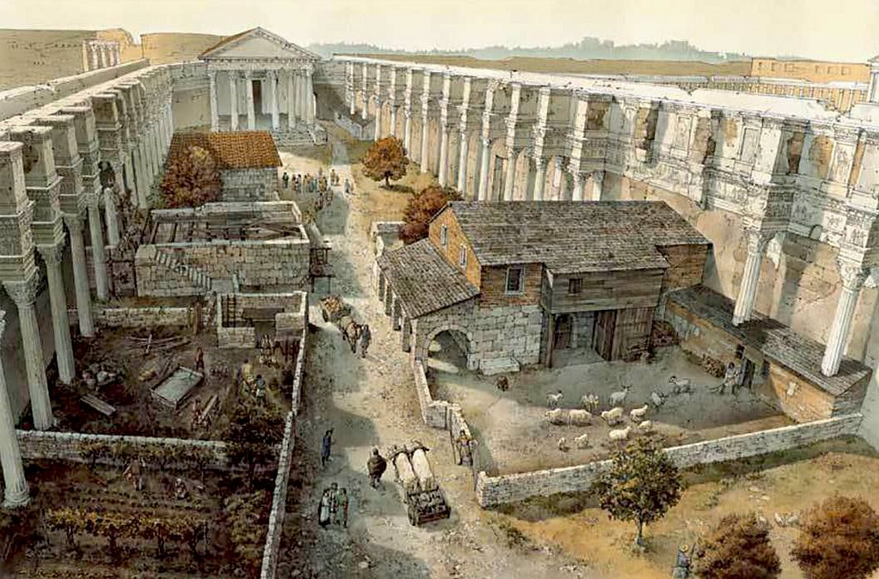

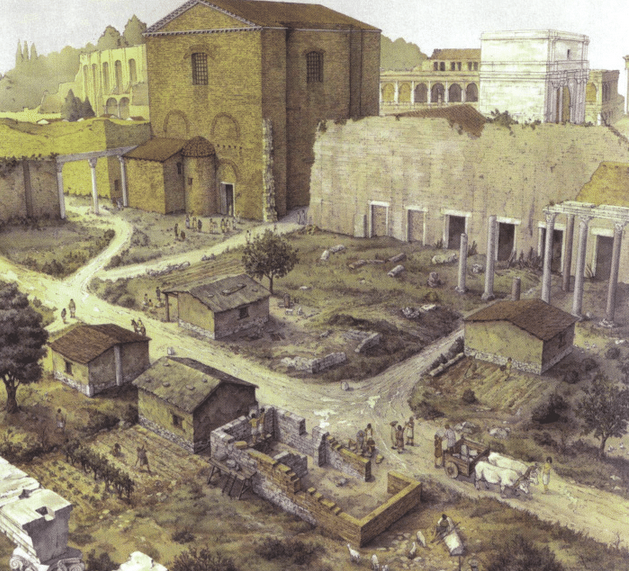

By the Romans of the Middle Ages

Since the days of the first barbarian invasions the Romans have gone on building with materials taken from the ancient temples, theatres, law-courts, baths and villas, stripping them of their gorgeous casings of marble, pulling down their walls for the sake of the blocks of travertine, setting up their own hovels on the top or in the midst of these majestic piles. Thus it has been with the memorials of paganism: a somewhat different cause has contributed to the disappearance of the mediæval churches.

By modern restorers of churches

What pillage, or fanaticism, or the wanton lust of destruction did in the one case, the ostentatious zeal of modern times has done in the other. The era of the final establishment of the Popes as temporal sovereigns of the city, is also that of the supremacy of the Renaissance style in architecture. After the time of Nicholas the Fifth, the pontiff against whom, it will be remembered, the spirit of municipal freedom made its last struggle in the conspiracy of Porcaro, nothing was built in Gothic, and the prevailing enthusiasm for the antique produced a corresponding dislike to everything mediæval, a dislike conspicuous in men like Julius the Second and Leo the Tenth, from whom the grandeur of modern Rome may be said to begin. Not long after their time the great religious movement of the sixteenth century, while triumphing in the north of Europe, was in the south met and overcome by a counter-reformation in the bosom of the old church herself, and the construction or restoration of ecclesiastical buildings became again the passion of the devout. No employment, whether it be called an amusement or a duty, could have been better suited to the court and aristocracy of Rome. They were indolent; wealthy, and fond of displaying their wealth; full of good taste, and anxious, especially when advancing years had chased away youth’s pleasures, to be full of good works also. Popes and cardinals and the heads of the great families vied with one another in building new churches and restoring or enlarging those they found till little of the old was left; raising over them huge cupolas, substituting massive pilasters for the single-shafted columns, adorning the interior with a profusion of rare marbles, of carving and gilding, of frescoes and altar-pieces by the best masters of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. None but a bigoted mediævalist can refuse to acknowledge the warmth of tone, the repose, the stateliness, of the churches of modern Rome; but even in the midst of admiration the sated eye turns away from the wealth of ponderous ornament, and we long for the clear pure colour, the simple yet grand proportions that give a charm to the buildings of an earlier age.

Existing relics of the Dark and Middle Ages

The Mosaics

Few of the ancient churches have escaped untouched; many have been altogether rebuilt. There are also some, however, in which the modernizers of the sixteenth and subsequent centuries have spared two features of the old structure, its round apse or tribune and its bell-tower. The apse has its interior usually covered with mosaics, exceedingly interesting, both from the ideas they express and as the only monuments of pictorial art that remain to us from the Dark Ages. To speak of them, however, as they deserve to be spoken of, would involve a digression for which there is no space here.

The Bell-towers

The campanile or bell-tower is a quaint little square brick tower, of no great height, usually standing detached from the church, and having in its topmost, sometimes also in its other upper stories, several arcade windows, divided by tiny marble pillars. What with these campaniles, then far more numerous than they are now, and with the huge brick fortresses of the nobles, towers must have held in the landscape of the mediæval city very much the part which domes do now. Although less imposing, they were probably more picturesque, the rather as in the earlier part of the Middle Ages the houses and churches, which are now mostly crowded together on the flat of the Campus Martius, were scattered over the heights and slopes of the Cœlian, Aventine, and Esquiline hills. Modern Rome lies chiefly on the opposite or north-eastern side of the Capitol, and the change from the old to the new site of the city, which can hardly be said to have distinctly begun before the destruction of the south-western part of the town by Robert Guiscard, was not completed until the sixteenth century. In A.D. 1536 the Capitol was rebuilt by Michael Angelo, in anticipation of the entry of Charles the Fifth, upon foundations that had been laid by the first Tarquin; and the palace of the Senator, the greatest municipal edifice of Rome, which had hitherto looked towards the Forum and the Coliseum, was made to front in the direction of St. Peter’s and the modern town.

Changed aspect of the city of Rome

The Rome of to-day is no more like the city of Rienzi than she is to the city of Trajan; just as the Roman church of the nineteenth century differs profoundly, however she may strive to disguise it, from the church of Hildebrand. But among all their changes, both church and city have kept themselves wonderfully free from the intrusion of foreign, at least of Teutonic, elements, and have faithfully preserved at all times something of an old Roman character.

Analogy between her architecture and her civil and ecclesiastical constitution

Latin Christianity inherited from the imperial system of old that firmly knit yet flexible organization, which was one of the grand secrets of its power: the great men whom mediæval Rome gave to or trained up for the Papacy were, like their progenitors, administrators, legislators, statesmen; seldom enthusiasts themselves, but perfectly understanding how to use and guide the enthusiasm of others—of the French and German crusaders, of men like Francis of Assisi and Dominic and Ignatius. Between Catholicism in Italy and Catholicism in Germany or England there was always, as there is still, a very perceptible difference. So also, if the analogy be not too fanciful, was it with Rome the city. Socially she seemed always drifting towards feudalism; yet she never fell into its grasp. Materially, her architecture was at one time considerably influenced by Gothic forms, yet Gothic never became, as in the rest of Europe, the dominant style. It approached Rome late, and departed from her early, so that we scarcely notice its presence, and seem to pass almost without a break from the old Romanesque to the Græco-Roman of the Renaissance.

Preservation of an antique character in both

Thus regarded, the history of the city, both in her political state and in her buildings, is seen to be intimately connected with that of the Holy Empire itself. The Empire in its title and its pretensions expressed the idea of the permanence of the institutions of the ancient world; Rome the city had, in externals at least, carefully preserved their traditions: the names of her magistracies, the character of her buildings, all spoke of antiquity, and gave it a strange and shadowy life in the midst of new races and new forms of faith.

Relation of the City and the Empire

In its essence the Empire rested on the feeling of the unity of mankind; it was the perpetuation of the Roman dominion by which the old nationalities had been destroyed, with the addition of the Christian element which had created a new nationality that was also universal. By the extension of her citizenship to all her subjects heathen Rome had become the common home, and, figuratively, even the local dwelling-place of the civilized races of man. By the theology of the time Christian Rome had been made the mystical type of humanity, the one flock of the faithful scattered over the whole earth, the holy city whither, as to the temple on Moriah, all the Israel of God should come up to worship. She was not merely an image of the mighty world, she was the mighty world itself in miniature. The pastor of her local church is also the universal bishop; the seven suffragans who consecrate him are the overseers of petty sees in Ostia, Antium, and the like, towns lying close round Rome: the cardinal priests and deacons who join these seven in electing him derive their title to be princes of the Church, the supreme spiritual council of the Christian world, from the incumbency of a parochial cure within the precincts of the city. Similarly, her ruler, the Emperor, is ruler of mankind; he is chosen by the acclamations of her people: he can be lawfully crowned nowhere but in one of her basilicas. She is, like Jerusalem of old, the mother of us all.

Extinction of the Florentine republic, A.D. 1530

There is yet another way in which the record of the domestic contests of Rome throws light upon the history of the Empire. From the eleventh century to the fifteenth her citizens ceased not to demand in the name of the old republic their freedom from the tyranny of the nobles and the Pope, and their right to rule over the world at large. These efforts—selfish and fantastic we may call them, yet men like Petrarch did not disdain to them their sympathy—issued from the same theories and were directed to the same ends as those which inspired Otto the Third and Frederick Barbarossa and Dante himself. They witness to the same incapacity to form any ideal for the future except a revival of the past; the same belief that one universal state is both desirable and possible, but possible only through the means of Rome: the same refusal to admit that a right which has once existed can ever be extinguished. In the days of the Renaissance these notions were passing silently away: the succeeding century brought with it misfortunes that broke the spirit of the nation. Italy was the battle-field of Europe: her wealth became the prey of a rapacious soldiery: the last and greatest of her republics was enslaved by an unfeeling Emperor, and handed over as the pledge of amity to a selfish Medicean Pope. When the hope of independence had been lost, the people turned away from politics to live for art and literature, and found, before many generations had passed, how little such exclusive devotion could compensate for the departure of freedom, and a national spirit, and the activity of civic life. A century after the golden days of Ariosto and Raphael, Italian literature had become frigid and affected, while Italian art was dying of mannerism.

Feelings of the modern Italians towards Rome

At length, after long ages of sloth, the stagnant waters were troubled. The Romans, who had lived in listless contentment under the paternal sway of the Popes, received new ideas from the advent of the revolutionary armies of France, and have found the Papal system, since its re-establishment fifty years ago as a modern bureaucratic despotism, far less tolerable than it was of yore. Our own days have seen the name of Rome become again a rallying-cry for the patriots of Italy, but in a sense most unlike the old one. The contemporaries of Arnold and Rienzi desired freedom only as a step to universal domination: their descendants, more wisely, yet not more from patriotism than from a pardonable civic pride, seek only to be the capital of the Italian kingdom. Dante prayed for a monarchy of the world, a reign of peace and Christian brotherhood: those who invoke his name as the earliest prophet of their creed strive after an idea that never crossed his mind—the national union of Italy.

Plain common-sense politicians in other countries do not understand this passion for Rome as a capital, and think it their duty to lecture the Italians on their flightiness. The latter do not themselves pretend that the shores of the Tiber are a suitable site for a capital: Rome is lonely, unhealthy, and in a bad strategical position; she has no particular facilities for trade: her people, with some fine qualities, are less orderly and industrious than the Tuscans or the Piedmontese. Nevertheless all Italy cries with one voice for Rome, firmly believing that national life can never thrill with a strong and steady pulsation till the ancient capital has become the nation’s heart. They feel that it is owing to Rome—Rome pagan as well as Christian—that they once played so grand a part in the drama of European history, and that they have now been able to attain that fervid sentiment of unity which has brought them at last together under one government. Whether they are right, whether if right they are likely to be successful, need not be inquired here. But it deserves to be noted that this enthusiasm for a famous name—for it is nothing more—is substantially the same feeling as that which created and hallowed the Holy Empire of the Middle Ages. The events of the last few years on both sides of the Atlantic have proved that men are not now, any more than they ever were, chiefly governed by calculations of material profit and loss. Sentiments, fancies, theories, have not lost their power; the spirit of poetry has not wholly passed away from politics. And strange as seems to us the worship paid to the name of mediæval Rome by those who saw the sins and the misery of her people, it can hardly have been an intenser feeling than is the imaginative reverence wherewith the Italians of to-day look on the city whence, as from a fountain, all the streams of their national life have sprung, and in which, as in an ocean, they are all again to mingle.