Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Essays Political, Historical, and Miscellaneous, Vol. III, by Archibald Alison (published 1850).

(Continued from Part 1)

The Itinéraire de Paris à Jerusalem is an account of the author’s journey in 1806, from Paris to Greece, Constantinople, Palestine, Egypt, and Carthage. This work is not so much a book of travels, as memoirs of the feelings and impressions of the author during a journey over the shores of the Mediterranean; the cradle, as Dr. Johnson observed, of all that dignifies and has blest human nature, of our laws, our religion, and our civilisation. It may readily be anticipated that the observations of such a man, in such scenes, must contain much that is interesting and delightful: our readers may prepare themselves for a high gratification; it is seldom that they have such an intellectual feast laid before them. We have translated the passages, both because there is no English version with which we are acquainted of this work, and because the translations which usually appear of French authors are executed in so slovenly a style.

On his first night amidst the ruins of Sparta, our author gives the following interesting account :—

“After supper Joseph brought me my saddle, which usually serves for my pillow. I wrapped myself in my cloak, and slept on the banks of the Eurotas under a laurel. The night was so clear and serene, that the Milky Way formed a resplendent arch, reflected in the waters of the river, and by the light of which I could read. I slept with my eyes turned towards the heavens, and with the constellation of the Swan of Leda directly above my head. Even at this distance of time I recollect the pleasure I experienced in sleeping thus in the woods of America, and still more in awakening in the middle of the night. I there heard the sound of the wind rustling through those profound solitudes, the cry of the stag and the deer, the fall of a distant cataract; while the fire at my feet, half-extinguished, reddened from below the foliage of the forest. I even experienced a pleasure from the voice of the Iroquois, when he uttered his cry in the midst of the untrodden woods, and by the light of the stars, amidst the silence of nature, proclaimed his unfettered freedom. Emotions such as these please at twenty years of age, because life is then so full of vigour that it suffices, as it were, for itself; and because there is something in early youth which incessantly urges towards the mysterious and the unknown; ipsi sibi somnia fingunt; but in a more mature age the mind reverts to more imperishable emotions; it inclines, most of all, to the recollections and the examples of history. I would still sleep willingly on the banks of the Eurotas and the Jordan, if the shades of the three hundred Spartans, or of the twelve sons of Jacob, were to visit my dreams; but I would no longer set out to visit lands which have never been explored by the plough. I now feel the desire for those old deserts which shroud the walls of Babylon or the legions of Pharsalia; fields of which the furrows are engraven on human thought, and where I may find man as I am, the blood, the tears, and the labours of man.”—Vol. i. 86, 87.

From Laconia our author directed his steps by the isthmus of Corinth to Athens. Of his first feelings in the ancient cradle of taste and genius, he gives the following beautiful description:—

“Overwhelmed with fatigue, I slept for some time without interruption, when I was at length awakened by the sound of Turkish music, proceeding from the summits of the Propyleum. At the same moment a Mussulman priest from one of the mosques called the faithful to pray in the city of Minerva. I cannot describe what I felt at the sound; that Iman had no need to remind one of the lapse of time; his voice alone in these scenes announced the revolution of ages.

“This fluctuation in human affairs is the more remarkable from the contrast which it affords to the unchangeableness of nature. As if to insult the instability of human affairs, the animals and the birds experience no change in their empires, nor alterations in their habits. I saw, when sitting on the hill of the Muses, the storks form themselves into a wedge, and wing their flight towards the shores of Africa. For two thousand years they have made the same voyage-they have remained free and happy in the city of Solon, as in that of the chief of the black eunuchs. From the height of their nests, which the revolutions below have not been able to reach, they have seen the races of men disappear; while impious generations have arisen on the tombs of their religious parents, the young stork has never ceased to nourish its aged parent. I involuntarily fell into these reflections, for the stork is the friend of the traveller: it knows the seasons of heaven.’ These birds were frequently my companions in the solitudes of America; I have often seen them perched on the wigwams of the savage; and when I saw them rise from another species of desert, from the ruins of the Parthenon, I could not avoid recognising a companion in the desolation of empires.

“The first thing which strikes a traveller in the monuments of Athens is their lovely colour. In our climate, where the heavens are charged with smoke and rain, the whitest stone soon becomes tinged with black and green. It is not thus with the atmosphere of the city of Theseus. The clear sky and brilliant sun of Greece have shed over the marble of Paros and Pentelicus a golden hue, comparable only to the finest and most fleeting tints of autumn.

“Before I saw these splendid remains, I had fallen into the ordinary error concerning them. I conceived they were perfect in their details, but that they wanted grandeur. But the first glance at the originals is sufficient to show that the genius of the architects has supplied, in the magnitude of proportion, what was wanting in size; and Athens is accordingly filled with stupendous edifices. The Athenians, a people far from rich, few in number, have succeeded in moving gigantic masses; the blocks of stone in the Pnyx and the Propyleum are literally quarters of rock. The slabs which stretch from pillar to pillar are of enormous dimensions: the columns of the Temple of Jupiter Olympius are above sixty feet in height, and the walls of Athens, including those which stretched to the Piræus, extended over nine leagues, and were so broad that two chariots could drive on them abreast. The Romans never erected more extensive fortifications. “By what strange fatality has it happened that the chefs d’œuvre of antiquity, which the moderns go so far to admire, have owed their destruction chiefly to the moderns themselves? The Parthenon was entire in 1687; the Christians at first converted it into a church, and the Turks into a mosque. The Venetians, in the middle of the light of the seventeenth century, bombarded the Acropolis with red-hot shot; a shell fell on the Parthenon, pierced the roof, communicated to a few barrels of powder, and blew into the air great part of the edifice, which did less honour to the gods of antiquity than the genius of man. No sooner was the town captured, than Morosini, in the design of embellishing Venice with its spoils, took down the statues from the front of the Temple; and another modern has completed, from love for the arts, that which the Venetian had begun. The invention of firearms has been fatal to the monuments of antiquity. Had the barbarians been acquainted with the use of gunpowder, not a Greek or Roman edifice would have survived their invasion; they would have blown up even the Pyramids in the search for hidden treasures. One year of war in our times will destroy more than a century of combats among the ancients. Everything among the moderns seems opposed to the perfection of art; their country, their manners, their dress, even their discoveries.” — Vol. i. 136, 145.

These observations are perfectly well founded. No one can have visited the monuments of the Greeks on the shores of the Mediterranean, without perceiving that they were thoroughly masters of an element of grandeur hitherto but little understood among the moderns—that arising from gigantic masses of stone. The feeling of sublimity which they produce is indescribable; it equals that of Gothic edifices of a thousand times the size. Every traveller must have felt this upon looking at the immense masses which rise in solitary magnificence on the plains at Stonehenge. The great block in the tomb of Agamemnon at Argos; those in the Cyclopean Walls of Volterra, and in the ruins of Agrigentum in Sicily, strike the beholder with a degree of astonishment bordering on awe. To have moved such enormous masses seems the work of a race of mortals superior in thought and power to this degenerate age; it is impossible, in visiting them, to avoid the feeling that you are beholding the work of giants. It is to this cause, we are persuaded, that the extraordinary impression produced by the Pyramids, and all the works of the Cyclopean age in architecture, is to be ascribed; and as it is an element of sublimity within the reach of all who have considerable funds at their command, it is earnestly to be hoped that it will not be overlooked by our architects. Strange that so powerful an ingredient in the sublime should have been lost sight of in proportion to the ability of the age to produce it, and that the monuments raised in the infancy of the mechanical art, should still be those in which alone it is to be seen to perfection!

We willingly translate the description of the unrivalled scene viewed from the Acropolis by the same poetical hand; a description so glowing, and yet so true, that it almost recalls, after the lapse of years, the fading tints of the original on the memory.

“To understand the view from the Acropolis, you must figure to yourself all the plain at its foot; bare and clothed in a dusky heath, intersected here and there by woods of olives, squares of barley, and ridges of vines; you must conceive the heads of columns, and the ends of ancient ruins, emerging from the midst of that cultivation; Albanian women washing their clothes at the fountain or the scanty streams; peasants leading their asses, laden with provisions, into the modern city: those ruins so celebrated, those isles, those seas, whose names are engraven on the memory, illumined by a resplendent light. I have seen from the rock of the Acropolis the sun rise between the two summits of Mount Hymettus: the ravens, which nestle round the citadel, but never fly over its summit, floating in the air beneath, their glossy wings reflecting the rosy tints of the morning: columns of light smoke ascending from the villages on the sides of the neighbouring mountains marked the colonies of bees on the far-famed Hymettus; and the ruins of the Parthenon were illuminated by the finest tints of pink and violet. The sculptures of Phidias, struck by a horizontal ray of gold, seemed to start from their marble bed by the depth and mobility of their shadows: in the distance, the sea and the Piræus were resplendent with light, while on the verge of the western horizon, the citadel of Corinth, glittering in the rays of the rising sun, shone like a rock of purple and fire.”—Vol. i. 149.

These are the colours of poetry; but beside this brilliant passage of French description, we willingly place the equally correct and still more thrilling lines of our own poet.

“Slow sinks, more beauteous ere his race be run,

Along Morea’s hills the setting sun,

Not as in northern clime obscurely bright,

But one unclouded blaze of living light;

O’er the hushed deep the yellow beams he throws,

Gilds the green wave that trembles as it glows;

On old Ægina’s rock and Idra’s isle,

The God of Gladness sheds his parting smile;

O’er his own regions lingering loves to shine,

Though there his altars are no more divine;

Descending fast, the mountain shadows kiss

Thy glorious gulf, unconquer’d Salamis!

Their azure arches through the long expanse,

More deeply purpled meet his mellowing glance,

And tenderest tints, along their summits driven,

Mark his gay course and own the hues of heaven,

Till, darkly shaded from the land and deep,

Behind his Delphian cliff he sinks to sleep.”

The columns of the temple of Jupiter Olympius produced the same effects on the enthusiastic mind of Chateaubriand as they do on every traveller. But he has added some reflections highly descriptive of the peculiar turn of his mind.

“At length we came to the great isolated columns placed in the quarter which is called the city of Adrian. On a portion of the architrave which unites two of the columns, is to be seen a piece of masonry, once the abode of a hermit. It is impossible to conceive how that building, which is still entire, could have been erected on the summit of one of these prodigious columns, whose height is above sixty feet. Thus this vast temple, at which the Athenians toiled for seven centuries, which all the kings of Asia laboured to finish, which Adrian, the ruler of the world, had first the glory to complete, has sunk under the hand of time, and the cell of a hermit has remained undecayed on its ruins. A miserable cabin is borne aloft on two columns of marble, as if fortune had wished to exhibit, on that magnificent pedestal, a monument of its triumph and its caprice.

“These columns, though twenty feet higher than those of the Parthenon, are far from possessing their beauty. The degeneracy of taste is apparent in their construction; but isolated and dispersed as they are, on a naked and desert plain, their effect is imposing in the highest degree. I stopped at their feet to hear the wind whistle through the Corinthian foliage on their summits; like the solitary palms which rise here and there amidst the ruins of Alexandria. When the Turks are threatened by any calamity, they bring a lamb into this place, and constrain it to bleat, with its face turned to heaven. Being unable to find the voice of innocence among men, they have recourse to the new-born lamb to mitigate the anger of heaven.”—Vol. i. 152, 153.

He followed the footsteps of Chandler along the Long Walls to the Piræus, and found that profound solitude in that once busy and animated scene, which is felt to be so impressive by every traveller.

“If Chandler was astonished at the solitude of the Piræus, I can safely assert that I was not less astonished than he. We had made the circuit of that desert shore; three harbours had met our eyes, and in all that space we had not seen a single vessel! The only spectacle to be seen was the ruins and the rocks on the shore—the only sounds that could be heard were the cry of the seafowl, and the murmur of the wave, which, breaking on the tomb of Themistocles, drew forth a perpetual sigh from the abode of eternal silence. Borne away by the sea, the ashes of the conqueror of Xerxes repose beneath the waves, side by side with the bones of the Persians. In vain I sought the Temple of Venus, the long gallery, and the symbolical statue which represented the Athenian people; the image of that implacable democracy was for ever fallen, beside the walls where the exiled citizens came to implore a return to their country. Instead of those superb arsenals, of those Agora resounding with the voice of the sailors; of those edifices which rivalled the beauty of the city of Rhodes, I saw nothing but a ruined convent and a solitary magazine. A single Turkish sentinel is perpetually seated on the coast; months and years revolve without a bark presenting itself to his sight. Such is the deplorable state into which these ports, once so famous, have now fallen. Who has overturned so many monuments of gods and men? The hidden power which overthrows everything, and is itself subject to the Unknown God whose altar St. Paul beheld at Phalera.”—Vol. i. 157, 158.

The fruitful theme of the decay of Greece has called forth many of the finest apostrophes of our moralists and poets. On this subject Chateaubriand offers the following striking observations:—

“One would imagine that Greece itself announced, by its mourning, the misfortunes of its children. In general, the country is uncultivated, the soil bare, rough, savage, of a brown and withered aspect. There are no rivers, properly so called, but little streams and torrents, which become dry in summer. No farm-houses are to be seen on the farms; no labourers, no chariots, no oxen, or horses of agriculture. Nothing can be figured so melancholy as to see the track of a modern wheel, where you can still trace in the worn parts of the rock the track of ancient wheels. Coast along that shore, bordered by a sea hardly more desolate; place on the summit of a rock a ruined tower, an abandoned convent; figure a minaret rising up in the midst of the solitude as a badge of slavery—a solitary flock feeding on a cape, surmounted by ruined columns—the turban of a Turk scaring the few goats which browse on the hills, and you will obtain a just idea of modern Greece.

“On the eve of leaving Greece, at the Cape of Sunium, I did not abandon myself alone to the romantic ideas which the beauty of the scene was fitted to inspire. I retraced in my mind the history of that country; I strove to discover in the ancient prosperity of Athens and Sparta the cause of their present misfortunes, and in their present situation the germ of future glory. The breaking of the sea, which insensibly increased against the rocks at the foot of the Cape, at length reminded me that the wind had risen, and that it was time to resume my voyage. We descended to the vessel, and found the sailors already prepared for our departure. We pushed out to sea, and the breeze, which blew fresh from the land, bore us rapidly towards Zea. As we receded from the shore, the columns of Sunium rose more beautiful above the waves their pure white appeared well defined in the dark azure of the distant sky. We were already far from the Cape; but we still heard the murmur of the waves, which broke on the cliffs at its foot, the whistle of the winds through its solitary pillars, and the cry of the sea-birds which wheel round the stormy promontory; they were the last sounds which I heard on the shores of Greece.”—Vol. i. 196.

“The Greeks did not excel less in the choice of the site of their edifices than in the forms and proportions. The greater part of the promontories of Peloponnesus, Attica, and Ionia, and the Islands of the Archipelago, are marked by temples, trophies, or tombs. These monuments, surrounded as they generally are with woods and rocks, beheld in all the changes of light and shadow, sometimes in the midst of clouds and lightning, sometimes by the light of the moon, sometimes gilded by the rising sun, sometimes flaming in his setting beams, throw an indescribable charm over the shores of Greece. The earth, thus decorated, resembles the old Cybele, who, crowned and seated on the shore, commanded her son Neptune to spread the waves beneath her feet.

“Christianity, to which we owe the sole architecture in unison with our manners, has also taught how to place our true monuments: our chapels, our abbeys, our monasteries, are dispersed on the summits of hills; not that the choice of the site was always the work of the architect, but that an art which is in unison with the feelings of the people, seldom errs far in what is really beautiful. Observe, on the other hand, how wretchedly almost all our edifices copied from the antique are placed. Not one of the heights around Paris is ornamented with any of the splendid edifices with which the city is filled. The modern Greek edifices resemble the corrupted language which they speak at Sparta and Athens: it is in vain to maintain that it is the language of Homer and Plato; a mixture of uncouth words, and of foreign constructions, betrays at every instant the invasion of the barbarians.

“To the loveliest sunset in nature succeeded a serene night. The firmament, reflected in the waves, seemed to sleep in the midst of the sea. The evening star, my faithful companion in my journey, was ready to sink beneath the horizon; its place could only be distinguished by the rays of light which it occasionally shed upon the water, like a dying taper in the distance. At intervals, the perfumed breeze from the islands which we passed entranced the senses, and agitated on the surface of the ocean the glassy image of the heavens.”—Vol. i. 182, 183.

The appearance of morning in the sea of Marmora is described in not less glowing colours.

“At four in the morning we weighed anchor, and as the wind was fair, we found ourselves in less than an hour at the extremity of the waters of the river. The scene was worthy of being described. On the right, Aurora rose above the headlands of Asia; on the left was extended the sea of Marmora; the heavens in the east were of a fiery red, which grew paler in proportion as the morning advanced; the morning star still shone in that empurpled light; and above it you could barely descry the pale circle of the moon. The picture changed while I still contemplated it; soon a blended glory of rays of rose and gold, diverging from a common centre, mounted to the zenith these columns were effaced, revived, and effaced anew, until the sun rose above the horizon, and confounded all the lesser shades in one universal blaze of light.”—Vol. i. 236.

His journey into the Holy Land awakened a new and not less interesting train of ideas, throughout the whole of which we recognise the peculiar features of M. de Chateaubriand’s mind: a strong and poetical sense of the beauties of nature a memory fraught with historical recollections-a deep sense of religion, manifested, however, rather as it affects the imagination and the passions than the judgment. It is a mere chimera to suppose that such aids are to be rejected by the friends of Christianity, or that truth may with safety discard the aid of fancy, either in subduing the passions or affecting the heart. On the contrary, every day’s experience must convince us that, for one who can understand an argument, hundreds can enjoy a romance; and that truth, to affect multitudes, must condescend to wear the garb of fancy. It is, no doubt, of vast importance that works should exist in which the truths of religion are unfolded with lucid precision, and its principles defined with the force of reason; but it is at least of equal moment that others should be found in which the graces of eloquence and the fervour of enthusiasm form an attraction to those who are insensible to graver considerations; where the reader is tempted to follow a path which he finds only strewed with flowers, and he unconsciously inhales the breath of eternal life.

“Cosi all Egro fanciul porgiamo aspersi

Di soave licor gli orsi del vaso,

Succhi amari ingannato intanto ei beve,

E dal inganno sua vita riceve.”

“On nearing the coast of Judea, the first visitors we received were three swallows. They were perhaps on their way from France, and pursuing their course to Syria. I was strongly tempted to ask them what news they brought from that paternal roof which I had so long quitted. I recollect that, in years of infancy, I spent entire hours in watching with an indescribable pleasure the course of swallows in autumn, when assembling in crowds previous to their annual migration: a secret instinct told me that I too should be a traveller. They assembled in the end of autumn around a great fishpond; there, amidst a thousand evolutions and flights in air, they seemed to try their wings, and prepare for their long pilgrimage. Whence is it that, of all the recollections in existence, we prefer those which are connected with our cradle? The illusions of self-love, the pleasures of youth, do not recur with the same charm to the memory; we find in them, on the contrary, frequent bitterness and pain; but the slightest circumstances revive in the heart the recollections of infancy, and always with a fresh charm. On the shores of the lakes in America, in an unknown desert, which was sublime only from the effect of solitude, a swallow has frequently recalled to my recollection the first years of my life; as here, on the coast of Syria, they recalled them in sight of an ancient land resounding with the traditions of history and the voice of ages.

“The air was so fresh and so balmy, that all the passengers remained on deck during the night. At six in the morning I was awakened by a confused hum; I opened my eyes, and saw all the pilgrims crowding towards the prow of the vessel. I asked what it was? they all replied, Signor, il Carmelo.’ I instantly rose from the plank on which I was stretched, and eagerly looked out for the sacred mountain. Every one strove to show it to me, but I could see nothing by reason of the dazzling of the sun, which now rose above the horizon. The moment had something in it that was august and impressive; all the pilgrims, with their chaplets in their hands, remained in silence, watching for the appearance of the Holy Land; the captain prayed aloud, and not a sound was to be heard but that prayer and the rush of the vessel, as it ploughed with a fair wind through the azure From time to time the cry arose, from those in elevated parts of the vessel, that they saw Mount Carmel, and at length I myself perceived it like a round globe under the rays of the sun. I then fell on my knees, after the manner of the Latin pilgrims. My first impression was not the kind of agitation which I experienced on approaching the coast of Greece, but the sight of the cradle of the Israelites, and of the country of Christ, filled me with awe and veneration. I was about to descend on the land of miracles -on the birthplace of the sublimest poetry that has ever appeared on earth -on the spot where, speaking only as it has affected human history, the most wonderful event has occurred which ever changed the destinies of the species. I was about to visit the scenes which had been seen before me by Godfrey of Bouillon, Raymond of Toulouse, Tancred the Brave, Richard Cœur-de-Lion, and Saint Louis, whose virtues even the infidels respected. How could an obscure pilgrim like myself dare to tread a soil ennobled by such recollections!”—Vol. i. 263-265.

Nothing is more striking in the whole work than the description of the Dead Sea and the Valley of Jordan. He has contrived to bring the features of that extraordinary scene more completely before us than any of the numerous English travellers who have preceded or followed him on the same route.

“We quitted the convent at three in the afternoon, ascended the torrent of Cedron, and at length, crossing the ravine, rejoined our route to the east. An opening in the mountain gave us a passing view of Jerusalem. I hardly recognised the city; it seemed a mass of broken rocks; the sudden appearance of that city of desolation in the midst of the wilderness had something in it almost terrifying. She was, in truth, the Queen of the Desert.

“As we advanced, the aspect of the mountains continued constantly the same, that is, a powdery white—without shade, a tree, or even moss. At half-past four, we descended from the lofty chain we had hitherto traversed, and wound along another of inferior elevation. At length we arrived at the last of the chain of heights, which close in on the west the Valley of Jordan and the Dead Sea. The sun was nearly setting; we dismounted from our horses, and I lay down to contemplate at leisure the lake, the valley, and the river.

“When you speak in general of a valley, you conceive it either cultivated or uncultivated; if the former, it is filled with villages, corn-fields, vineyards, and flocks; if the latter, it presents grass or forests; if it is watered by a river, that river has windings, and the sinuosities or projecting points afford agreeable and varied landscapes. But here there is nothing of the kind. Conceive two long chains of mountains running parallel from north to south, without projections, without recesses, without vegetation. The ridge on the east, called the Mountains of Arabia, is the most elevated; viewed at the distance of eight or ten leagues, it resembles a vast wall, extremely similar to the Jura, as seen from the Lake of Geneva, from its form and azure tint. You can perceive neither summits nor the smallest peaks; only here and there slight inequalities, as if the hand of the painter who traced the long lines on the sky had occasionally trembled.

“The chain on the eastern side forms part of the mountains of Judea— less elevated and more uneven than the ridge on the west: it differs also in its character; it exhibits great masses of rock and sand, which occasionally present all the varieties of ruined fortifications, armed men, and floating banners. On the side of Arabia, on the other hand, black rocks, with perpendicular flanks, spread from afar their shadows over the waters of the Dead Sea. The smallest bird could not find in those crevices of rock a morsel of food; everything announces a country which has fallen under the divine wrath; everything inspires the horror at the incest from whence sprang Ammon and Moab.

“The valley which lies between these mountains resembles the bottom of a sea, from which the waves have long ago withdrawn: banks of gravel, a dried bottom, rocks covered with salt, deserts of moving sand: here and there stunted arbutus shrubs grow with difficulty on that arid soil; their leaves are covered with the salt which had nourished their roots, while their bark has the scent and taste of smoke. Instead of villages, nothing but the ruins of towers are to be seen. Through the midst of the valley flows a discoloured stream, which seems to drag its lazy course unwillingly towards the lake. Its course is not to be discerned by the water, but by the willows and shrubs which skirt its banks—the Arab conceals himself in these thickets to waylay and rob the pilgrim.

“Such are the places rendered famous by the malediction of Heaven: that river is the Jordan—that lake is the Dead Sea. It appears with a serene surface; but the guilty cities which are embosomed in its waves have poisoned its waters. Its solitary abysses can sustain the life of no living thing; no vessel ever ploughed its bosom; its shores are without trees, without birds, without verdure; its water, frightfully salt, is so heavy that the highest wind can hardly raise it.

“In travelling in Judea, an extreme feeling of ennui frequently seizes the mind, from the sterile and monotonous aspect of the objects which are presented to the eye; but when journeying on through these pathless deserts, the expanse seems to spread out to infinity before you, the ennui disappears, and a secret terror is experienced, which, far from lowering the soul, elevates and inflames the genius. These extraordinary scenes reveal the land desolated by miracles; that burning sun, the impetuous eagle, the barren figtree—all the poetry, all the pictures of Scripture are there. Every name recalls a mystery; every grotto speaks of the life to come; every peak re-echoes the voice of a prophet. God Himself has spoken on these shores: these dried-up torrents, these cleft rocks, these tombs rent asunder, attest His resistless hand: the desert appears mute with terror; and you feel that it has never ventured to break silence since it heard the voice of the Eternal.”—Vol. i. 317.

“I employed two complete hours in wandering on the shores of the Dead Sea, notwithstanding the remonstrances of the Bedouins, who pressed me to quit that dangerous region. I was desirous of seeing the Jordan, at the place where it discharges itself into the lake; but the Arabs refused to lead me thither, because the river, at a league from its mouth, makes a detour to the left, and approaches the mountains of Arabia. It was necessary, therefore, to direct our steps towards the curve which was nearest us. We struck our tents, and travelled for an hour and a half with excessive difficulty, through a fine and silvery sand. We were moving towards a little wood of willows and tamarinds, which, to my great surprise, I perceived growing in the midst of the desert. All of a sudden the Bethlemites stopped, and pointed to something at the bottom of a ravine, which had not yet attracted my attention. Without being able to say what it was, I perceived a sort of sand rolling on through the fixed banks which surrounded it. I approached it, and saw a yellow stream which could hardly be distinguished from the sand of its two banks. It was deeply furrowed through the rocks, and with difficulty rolled on, a stream surcharged with sand: it was the Jordan.

“I had seen the great rivers of America, with the pleasure which is inspired by the magnificent works of nature. I had hailed the Tiber with ardour, and sought with the same interest the Eurotas and the Cephisus; but on none of these occasions did I experience the intense emotion which I felt on approaching the Jordan. Not only did that river recall the earliest antiquity, and a name rendered immortal in the finest poetry, but its banks were the theatre of the miracles of our religion. Judea is the only country which recalls at once the earliest recollections of man, and our first impressions of heaven; and thence arises a mixture of feeling in the mind, which no other part of the world can produce.”—Vol. i. 327, 328.

The peculiar turn of his mind renders our author, in an especial manner, partial to the description of sad and solitary scenes. The following description of the Valley of Jehoshaphat is in his best style:—

“The Valley of Jehoshaphat has in all ages served as the burying-place to Jerusalem you meet there, side by side, monuments of the most distant times and of the present century. The Jews still come there to die, from all the corners of the earth. A stranger sells to them, for almost its weight in gold, the land which contains the bones of their fathers. Solomon planted that valley: the shadow of the Temple by which it was overhung—the torrent, called after grief, which traversed it—the Psalms which David there composed—the Lamentations of Jeremiah, which its rocks re-echoed, render it the fitting abode of the tomb. Jesus Christ commenced his Passion in the same place: that innocent David there shed, for the expiation of our sins, those tears which the guilty David let fall for his own transgressions. Few names awaken in our minds recollections so solemn as the Valley of Jehoshaphat. It is so full of mysteries, that, according to the Prophet Joel, all mankind will be assembled there before the Eternal Judge.

“The aspect of this celebrated valley is desolate; the western side is bounded by a ridge of lofty rocks which support the walls of Jerusalem, above which the towers of the city appear. The eastern is formed by the Mount of Olives, and another eminence called the Mount of Scandal, from the idolatry of Solomon. These two mountains, which adjoin each other, are almost bare, and of a red and sombre hue; on their desert side you see here and there some black and withered vineyards, some wild olives, some ploughed land, covered with hyssop, and a few ruined chapels. At the bottom of the valley, you perceive a torrent, traversed by a single arch, which appears of great antiquity The stones of the Jewish cemetery appear like a mass of ruins at the foot of the Mountain of Scandal, under the village of Siloam. You can hardly distinguish the buildings of the village from the ruins with which they are surrounded. Three ancient monuments are particularly conspicuous: those of Zachariah, Jehoshaphat, and Absalom. The sadness of Jerusalem, from which no smoke ascends, and in which no sound is to be heard; the solitude of the surrounding mountains, where not a living creature is to be seen; the disorder of those tombs, ruined, ransacked, and half-exposed to view, would almost induce one to believe that the last trump had been heard, and that the dead were about to rise in the Valley of Jehoshaphat.”—Vol. ii. 34, 35.

Chateaubriand, after visiting with the devotion of a pilgrim the Holy Sepulchre, and all the scenes of our Saviour’s sufferings, spent a day in examining the scenes of the Crusaders’ triumphs, and comparing the descriptions in Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered with the places where the events which they recorded actually occurred. He found them in general so extremely exact, that it was difficult to avoid the conviction that the poet had been on the spot. He even fancied he discovered the scene of the Flight of Erminia, and the inimitable combat and death of Clorinda.

From the Holy Land he sailed to Egypt; and we have the following graphic picture of the approach to that cradle of art and civilisation:—

“On the 20th October, at five in the morning, I perceived on the green and ruffled surface of the water a line of foam, and beyond it a pale and still ocean. The captain clapped me on the shoulder, and said in French, ‘Nile;’ and soon we entered and glided through those celebrated waters. A few palm-trees and a minaret announce the situation of Rosetta, but the town itself is invisible. These shores resemble those of the coast of Florida; they are totally different from those of Italy or Greece; everything recalls the tropical regions.

“At ten o’clock we at length discovered, beneath the palm-trees, a line of sand which extended westward to the promontory of Aboukir, before which we were obliged to pass before arriving opposite to Alexandria. At five in the evening the shore suddenly changed its aspect. The palm-trees seemed planted in lines along the shore, like the elms along the roads in France. Nature appears to take a pleasure in thus recalling the ideas of civilisation in a country where that civilisation first arose, and barbarism has now resumed its sway. It was eleven o’clock when we cast anchor before the city, and as it was some time before we could get ashore, I had full leisure to follow out the contemplation which the scene awakened.

“I saw on my right several vessels, and the castle, which stands on the site of the Tower of Pharos. On my left, the horizon seemed shut in by sand-hills, ruins, and obelisks; immediately in front extended a long wall, with a few houses appearing above it; not a light was to be seen on shore, and not a sound came from the city. This, nevertheless, was Alexandria, the rival of Nemphis and Thebes, which once contained three millions of inhabitants, which was the sanctuary of the Muses, and the abode of science amidst a benighted world. Here were heard the orgies of Antony and Cleopatra, and here was Cæsar received with more than regal splendour by the Queen of the East. But in vain I listened. A fatal talisman had plunged the people into a hopeless calm: that talisman is the despotism which extinguishes every joy, which stifles even the cry of suffering. And what sound could arise in a city of which at least a third is abandoned; another third of which is surrounded only by the tombs of its former inhabitants; and of which the third which still survives between those dead extremities, is a species of breathing trunk, destitute of the force even to shake off its chains, and placed between ruins and the tomb?”—Vol. ii. 163.

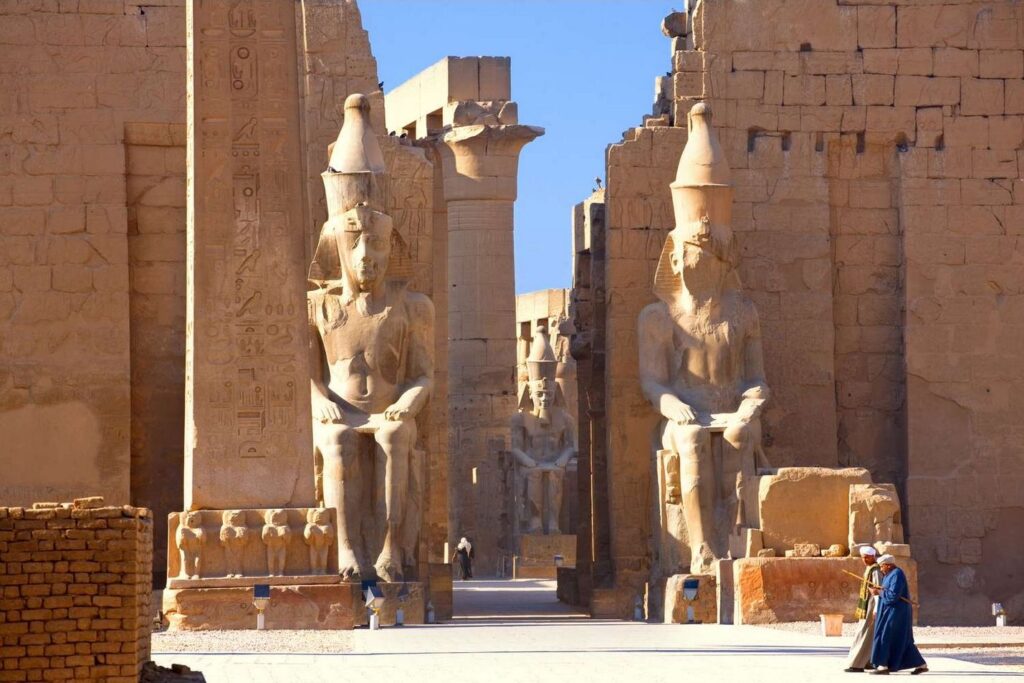

It is to be regretted that Chateaubriand did not visit Upper Egypt. His ardent and learned mind would have found ample room for eloquent declamation amidst the gigantic ruins of Luxor, and the Sphinx avenues of Thebes. The inundation of the Nile, however, prevented him from seeing even the Pyramids nearer than Grand Cairo; and when on the verge of that interesting region, he was compelled unwillingly to retrace his steps to the French shores. After a tempestuous voyage along the coast of Libya, he cast anchor off the ruins of Carthage; and thus he describes his feelings on surveying those venerable remains:—

“From the summit of Byrsa the eye embraces the ruins of Carthage, which are more considerable than are generally imagined: they resemble those of Sparta, having nothing well preserved, but embracing a considerable space. I saw them in the middle of February: the olives, the fig-trees, were already bursting into leaf: large bushes of angelica and acanthus formed tufts of verdure, amidst the remains of marble of every colour. In the distance, I cast my eyes over the Isthmus, the double sea, the distant isles, a cerulean sea, a smiling plain, and azure mountains. I saw forests, and vessels, and aqueducts; Moorish villages, and Mahometan hermitages; glittering minarets, and the white buildings of Tunis. Surrounded with the most touching recollections, I thought alternately of Dido, Sophonisba, and the noble wife of Asdrubal; I contemplated the vast plains where the legions of Hannibal, Scipio, and Cæsar were buried: My eyes sought for the sight of Utica. Alas! The remains of the palace of Tiberius still exist in the island of Capri, and you search in vain at Utica for the house of Cato. Finally, the terrible Vandals, the rapid Moors, passed before my recollection, which fixed at last on Saint Louis expiring on that inhospitable shore. May the story of the death of that prince terminate this itinerary; fortunate to re-enter, as it were, into my country by the ancient monument of his virtues, and to close at the sepulchre of that King of holy memory my long pilgrimage to the tombs of illustrious men.”—Vol. ii. 257, 258.

“As long as his strength permitted, the dying monarch gave instructions to his son Philip; and when his voice failed him, he wrote with a faltering hand these precepts, which no Frenchman, worthy of the name, will ever be able to read without emotion. My son, the first thing which I enjoin you is to love God with all your heart; for without that no man can be saved. Beware of violating His laws; rather endure the worst torments than sin against His commandments. Should He send you adversity, receive it with humility, and bless the hand which chastens you; and believe that you have well deserved it, and that it will turn to your weal. Should He try you with prosperity, thank Him with humility of heart, and be not elated by His goodness. Do justice to every one, as well the poor as the rich. Be liberal, free, and courteous to your servants, and cause them to love as well as fear you. Should any controversy or tumult arise, sift it to the bottom, whether the result be favourable or unfavourable to your interests. Take care, in an especial manner, that your subjects live in peace and tranquillity under your reign. Respect and preserve their privileges, such as they have received them from their ancestors, and preserve them with care and love. And now, I give you every blessing which a father can bestow on his child; praying the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, that they may defend you from all adversities; and that we may again, after this mortal life is ended, be united before God, and adore His majesty for ever!'”—Vol. ii. 264.

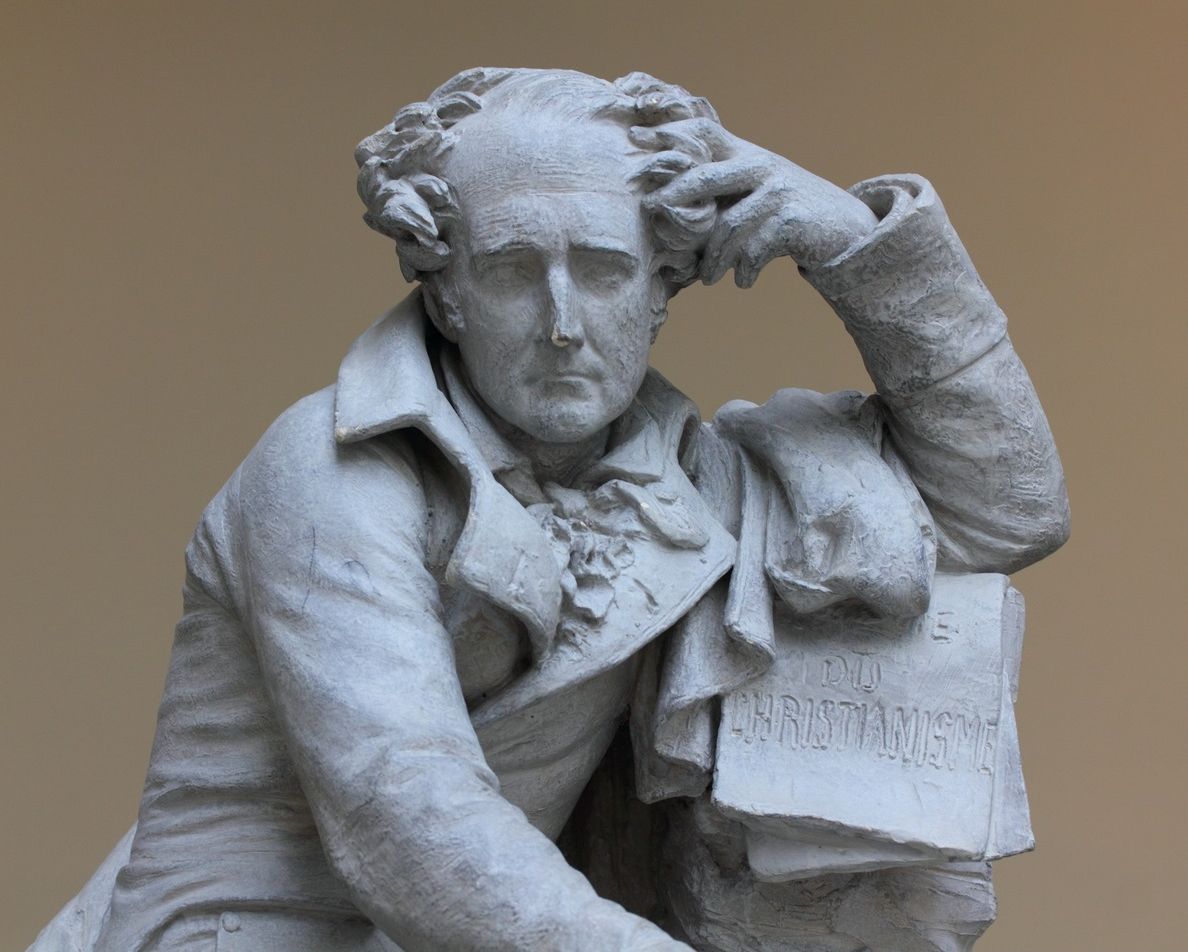

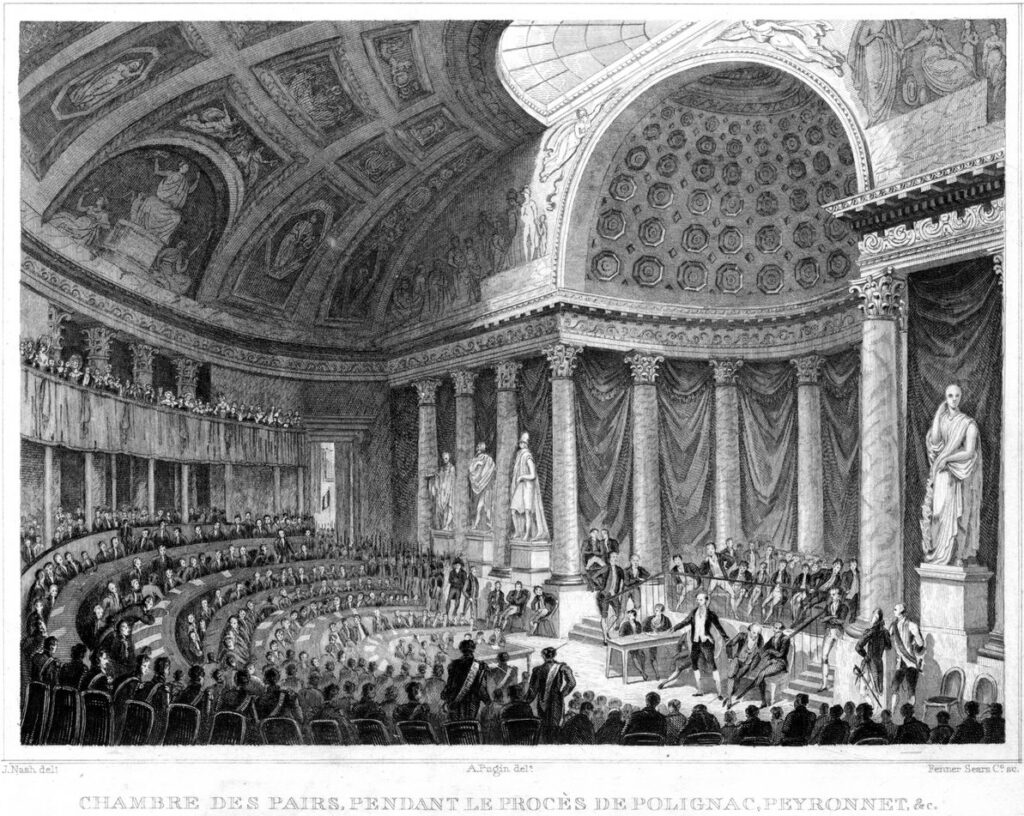

“The style of Chateaubriand,” says Napoleon, “is not that of Racine, it is that of a prophet; he has received from nature the sacred flame; it breathes in all his works.”[1] It is of no common man—being a political opponent—that Napoleon would have said these words. Chateaubriand had done nothing to gain favour with the French Emperor; on the contrary, he irritated him by throwing up his employment and leaving his country, upon the assassination of the Duke d’Enghien. In truth, nothing is more remarkable, amidst the selfishness of political apostasy in France, than the uniform consistence and disinterestedness of this great man’s opinions. His principles, indeed, were not all the same at fifty as at twenty-five; we should be glad to know whose are, excepting those who are so obtuse as to derive no light from the extension of knowledge and the acquisitions of experience? Change is so far from being despicable, that it is highly honourable in itself, and when it proceeds from the natural modification of the mind from the progress of years, or the lessons of more extended experience. It becomes contemptible only when it arises on the suggestions of interest, or the desires of ambition. Now, Chateaubriand’s changes of opinion have all been in opposition to his interest; and he has suffered at different periods of his life from his resistance to the mandates of authority, and his rejection of the calls of ambition. In early life he was exiled from France, and shared in all the hardships of the emigrants, from his attachment to Royalist principles. At the earnest request of Napoleon, he accepted office under the Imperial Government, but he relinquished it, and again became an exile upon the murder of the Duke d’Enghien. The influence of his writings was so powerful in favour of the Bourbons, at the period of the Restoration, that Louis XVIII truly said, they were worth more than an army. He followed the dethroned monarch to Ghent, and contributed much, by his powerful genius, to consolidate the feeble elements of his power, after the fall of Napoleon. Called to the helm of affairs in 1824, he laboured to accommodate the temper of the monarchy to the increasing spirit of freedom in the country, and fell into disgrace with the Court, and was distrusted by the Royal Family, because he strove to introduce those popular modifications into the administration of affairs, which might have prevented the Revolution of July; and finally, he has resisted all the efforts of the Citizen King to engage his great talents in defence of the throne of the Barricades. True to his principles, he has exiled himself from France, to preserve his independence; and consecrated in a foreign land his illustrious name to the defence of the child of misfortune.

Chateaubriand is not only an eloquent and beautiful writer, he is also a profound scholar, and an enlightened thinker. His knowledge of history and classical literature is equalled only by his intimate acquaintance with the early annals of the church, and the fathers of the Catholic faith; while in his speeches delivered in the Chamber of Peers since the Restoration, will be found not only the most eloquent, but the most complete and satisfactory dissertations on the political state of France during that period, which are anywhere to be met with. It is a singular circumstance, that an author of such great and varied acquirements, who is universally allowed by all parties in France to be their greatest living writer, should hardly be known except by name to the great body of readers in this country.

His greatest work, that on which his fame will rest with posterity, is the Genius of Christianity, from which such ample quotations have already been given. The next is the Martyrs, a romance, in which he has introduced an exemplification of the principles of Christianity, in the early sufferings of the primitive church, and enriched the narrative by the splendid description of the scenery in Egypt, Greece, and Palestine, which he had visited during his pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and all the stores of learning which a life spent in classical and ecclesiastical lore could accumulate. The last of his considerable publications is the Etudes Historiques, a work eminently characteristic of that superiority in historical composition, which we have allowed to the French modern writers over their contemporaries in this country; and which, we fear, another generation, instructed when too late by the blood and the tears of a Revolution, will alone be able fully to appreciate. Its object is to trace the influence of Christianity from its first spread in the Roman empire to the rise of civilisation in the Western world; a field in which he goes over the ground trod by Gibbon, and demonstrates the unbounded benefits derived from religion in all the institutions of modern times. In this noble undertaking he has been aided, with a still more philosophical mind, though inferior fire and eloquence, by Guizot a writer who, equally with his illustrious rival, is as yet unknown, save by report, in this country, but from whose joint labours is to be dated the spring of a pure and philosophical system of religious inquiry in France, and the commencement of that revival of manly devotion in which the antidote, and the only antidote, to the fanaticism of infidelity is to be found.

(1757-1839)

_______________________________________

[1] Memoirs of Napoleon, iv. 342.