Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Essays Political, Historical, and Miscellaneous, Vol. III, by Archibald Alison (published 1850).

[BLACKWOOD’S MAGAZINE, March 1832]

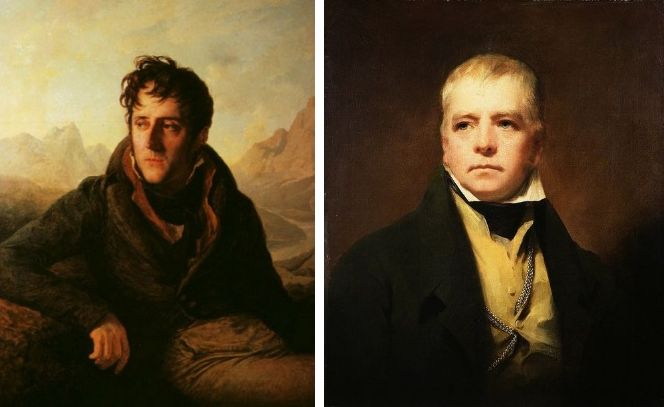

Chateaubriand is universally allowed by the French, of all parties, to be their first writer. His merits, however, are but little understood in this country. He is known as once a minister of Louis XVIII, and ambassador of that monarch in London; as the writer of many celebrated political pamphlets; and the victim, since the Revolution of 1830, of his noble and ill-requited devotion to the unfortunate family. Few are aware that he is, without one single exception, the most eloquent writer of the present age; that, independent of politics, he has produced many works on morals, religion, and history, destined for lasting endurance; that his writings combine the strongest love of rational freedom with the warmest inspiration of Christian devotion; that he is, as it were, the link between the feudal and the revolutionary ages—retaining from the former its generous and elevated feeling, and inhaling from the latter its acute and fearless investigation. The last pilgrim, with devout feelings, to the Holy Sepulchre, he was the first supporter of constitutional freedom in France; discarding thus from former times their bigoted fury, and from modern, their infidel spirit; blending all that was noble in the ardour of the Crusades, with all that is generous in the enthusiasm of freedom.

It is the glory of the Conservative Party throughout the world—and by this party we mean all who are desirous in every country to uphold the religion, the institutions, and the liberties of their fathers—that the two greatest writers of the age have devoted their talents to the support of their principles. Sir Walter Scott and Chateaubriand are beyond all question, and by the consent of both nations, at the head of the literature of France and England since the Revolution; and they will both leave names at which the latest posterity will feel proud, when the multitudes who have sought to rival them on the revolutionary side are buried in the waves of forgotten time. It is no small triumph to the cause of order in these trying days, that these mighty spirits, destined to instruct and bless mankind through every succeeding age, should have proved so true to the principles of virtue; and the patriot may well rejoice that generations yet unborn, while they approach their immortal shrines, or share in the enjoyments derived from the legacies they have bequeathed to mankind, will inhale only a holy spirit, and derive from the pleasures of imagination nothing but additional inducements to the performance of duty.

Both these great men are now under an eclipse, too likely, in one at least, to terminate in earthly extinction. The first lies on the bed, if not of material, at least, it is to be feared, of intellectual death; and the second, arrested by the military despotism which he so long strove to avert from his country, has lately awaited in the solitude of a prison the fate destined for him by revolutionary violence.[1] But

“Stone walls do not a prison make,

Nor iron bars a cage;

Minds innocent and quiet take

That for an hermitage.”

It is in such moments of gloom and depression, when the fortune of the world seems most adverse, when the ties of mortality are about to be dissolved, or the career of virtue is on the point of being terminated, that the immortal superiority of genius and virtue most strongly appear. In vain is the Scottish bard extended on the bed of sickness, and the French patriot confined to the gloom of a dungeon; their works remain to perpetuate their lasting sway over the minds of men; and while their mortal frames are sinking beneath the sufferings of the world, their immortal souls rise into the region of spirits, to witness a triumph more glorious, an ascendency more enduring, than ever attended the arms of Cæsar or Alexander.

Though pursuing the same pure and ennobling career, though gifted with the same ardent imagination, and steeped in the same fountains of ancient lore, no two writers were ever more different than Chateaubriand and Sir Walter Scott. The great characteristic of the French author, is the impassioned and enthusiastic turn of his mind. Master of immense information, thoroughly imbued at once with the learning of classical and catholic times; gifted with a retentive memory, a poetical fancy, and a painter’s eye, he brings to bear upon every subject the force of erudition, the images of poetry, the charm of varied scenery, and the eloquence of impassioned feeling. Hence his writings display a reach and variety of imagery, a depth of light and shadow, a vigour of thought, and an extent of illustration, to which there is nothing comparable in any other writer, ancient or modern, with whom we are acquainted. All that he has seen, or read, or heard, seems present to his mind, whatever he does, or wherever he is. He illustrates the genius of Christianity by the beauties of classical learning; inhales the spirit of ancient prophecy on the shores of the Jordan; dreams on the banks of the Eurotas of the solitude and gloom of the American forests; visits the Holy Sepulchre with a mind alternately excited by the devotion of a pilgrim, the curiosity of an antiquary, and the enthusiasm of a crusader; and combines in his romances, with the tender feelings of chivalrous love, the heroism of Roman virtue and the sublimity of Christian martyrdom. His writings are less a faithful portrait of any particular age or country, than an assemblage of all that is grand, and generous, and elevated in human nature. He drinks deep of inspiration at all the fountains where it has ever been poured forth to mankind, and delights us less by the accuracy of any particular picture, than by the traits of genius which he has combined from every quarter where its footsteps have trod. His style seems formed on the lofty strains of Isaiah, or the beautiful images of the Book of Job, more than all the classical or modern literature with which his mind is so amply stored. He is admitted by all Frenchmen, of whatever party, to be the most perfect living master of their language, and to have gained for it beauties unknown to the age of Bossuet and Fenelon. Less polished in his periods, less sonorous in his diction, less melodious in his rhythm, than these illustrious writers, he is incomparably more varied, rapid, and energetic; his ideas flow in quicker succession, his words follow in more striking antithesis; the past, the present, and the future rise up at once before us; and we see how strongly the stream of genius, instead of gliding down the smooth current of ordinary life, has been broken and agitated by the cataract of revolution.

With far less classical learning, fewer images derived from travelling, inferior information on many historical subjects, and a mind of a less impassioned and energetic cast, our own Sir Walter is far more deeply read in that book which is ever the same—the human heart. This is his unequalled excellence: there he stands, without a rival since the days of Shakespeare. It is to this cause that his astonishing success has been owing. We feel in his characters that it is not romance, but real life which is represented. Every word that is said, especially in the Scotch novels, is nature itself. Homer, Cervantes, Shakespeare, and Scott, alone have penetrated to the deep substratum of character, which, however disguised by the varieties of climate and government, is at bottom everywhere the same; and thence they have found a responsive echo in every human heart. Every man who reads these admirable works, from the North Cape to Cape Horn, feels that what the characters they contain are made to say, is just what would have occurred to themselves, or what they have heard said by others as long as they lived. Nor is it only in the delineation of character, and the knowledge of human nature, that the Scottish novelist, like his great predecessors, is but for them without a rival. Powerful in the pathetic, admirable in dialogue, unmatched in description, his writings captivate the mind as much by the varied excellencies which they exhibit, as by the powerful interest which they maintain. He has carried romance out of the region of imagination and sensibility into the walks of actual life. We feel interested in his characters, not because they are ideal beings with whom we have become acquainted for the first time when we began the book, but because they are the very persons we have lived with from our infancy. His descriptions of scenery are not luxuriant and glowing pictures of imaginary beauty, like those of Mrs. Radcliffe, having no resemblance to actual nature, but faithful and graphic portraits of real scenes, drawn with the eye of a poet, but the fidelity of a consummate draughtsman. He has combined historical accuracy and romantic adventure with the interest of tragic events: we live with the heroes, and princes, and paladins of former times, as with our own contemporaries; and acquire from the splendid colouring of his pencil such a vivid conception of the manners and pomp of the feudal ages, that we confound them, in our recollections, with the scenes which we ourselves have witnessed. The splendour of their tournaments, the magnificence of their dress, the glancing of their arms; their haughty manners, daring courage, and knightly courtesy; the shock of their battle-steeds, the splintering of their lances, the conflagration of their castles, are brought before our eyes in such vivid colours, that we are at once transported to the age of Richard and Saladin, of Bruce and Marmion, of Charles the Bold and Philip Augustus. Disdaining to flatter the passions, or pander to the ambition of the populace, he has done more than any man alive to elevate their character, to fill their minds with the noble sentiments which dignify alike the cottage and the palace, to exhibit the triumph of virtue in the humblest stations over all that the world calls great, and, without ever indulging a sentiment which might turn them from the scenes of their real usefulness, to bring home to every mind the “might that slumbers in a peasant’s arm.” Above all, he has uniformly, in all his varied and extensive productions, shown himself true to the cause of virtue. Amidst all the innumerable combinations of character, event, and dialogue, which he has formed, he has ever proved faithful to the polar star of duty; and alone, perhaps, of the great romance writers of the world, has not left a line which on his deathbed he would wish recalled.

Of such men France and England may well be proud; shining, as they already do, through the clouds and the passions of a fleeting existence, they are destined soon to illuminate the world with a purer lustre, and ascend to that elevated station in the higher heavens where the fixed stars shed a splendid and imperishable light. The writers whom party has elevated, the genius which vice has seduced, are destined to decline with the interests to which they were devoted, or the passions by which they were misled. The rise of new political struggles will consign to oblivion the vast talent which was engulfed in the contention; the accession of a more virtuous age buries in the dust the fancy which was enlisted in the cause of corruption; while these illustrious men, whose writings have struck root in the inmost recesses of the human heart, and been watered by the streams of imperishable feeling, will for ever continue to elevate and bless a grateful world.

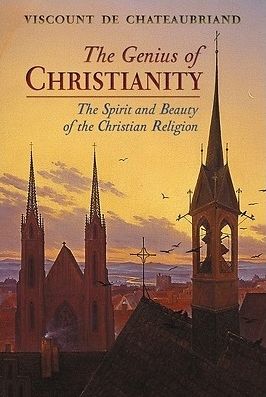

To form a just conception of the importance of Chateaubriand’s Genius of Christianity, we must recollect the period when it was published, the character of the works it was intended to combat, and the state of society in which it was destined to appear. For half a century before it appeared, the whole genius of France had been incessantly directed to undermine the principles of religion. The days of Pascal and Fenelon, of Saurin and Bourdaloue, of Bossuet and Massillon, had passed away; the splendid talent of the seventeenth century was no longer arrayed in the support of virtue; the supremacy of the church had ceased to be exerted to thunder in the ear of princes the awful truths of judgment to come. Borne away in the torrent of corruption, the church itself had yielded to the increasing vices of the age; its hierarchy had become involved in the passions they were destined to combat; and the cardinal’s purple covered the shoulders of an associate in the midnight orgies of the Regent Orleans. Such was the audacity of vice, the recklessness of fashion, and the supineness of religion, that Madame Roland tells us, what astonished her in her youthful days was, that the heaven itself did not open to rain down upon the guilty metropolis, as on the cities of the Jordan, a tempest of consuming fire.

While such was the profligacy of power and the audacity of crime, philosophic talent lent its aid to overwhelm the remaining safeguards of religious belief. The middle and the lower orders could not, indeed, participate in the luxurious vices of their wealthy superiors, but they could well be persuaded that the faith which permitted such enormities, the religion which was stained by such crimes, was a system of hypocrisy and deceit. The passion for innovation, which more than any other feature characterised that period in France, invaded the precincts of religion as well as the bulwarks of the state: the throne and the altar, the restraints of this world and the next, as is ever the case, crumbled together. For half a century, all the genius of France had been incessantly directed to overturn the sanctity of Christianity; its corruptions were represented as its very essence, its abuses as part of its necessary effects. Ridicule, ever more powerful than reason with a frivolous age, lent its aid to overturn the defenceless fabric; and for more than one generation, not one writer of note had appeared to maintain the hopeless cause. Voltaire and Diderot, d’Alembert and Raynal, Laplace and Lagrange, had lent the weight of their illustrious names, or the powers of their versatile minds, to carry on the war. The Encyclopedie was a vast battery of infidelity incessantly directed against Christianity; while the crowd of licentious novelists, with which the age abounded—Louvet, Crebillon, Laclos, and a host of others—insinuated the poison, mixed up with the strongest allurements to the passions, and the most voluptuous seductions to the senses.

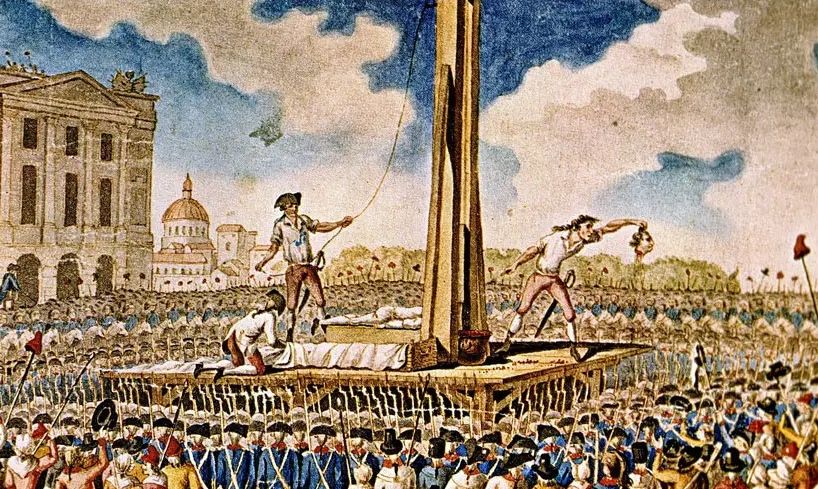

This inundation of infidelity was soon followed by sterner days; to the unrestrained indulgence of passion succeeded the unfettered march of crime. With the destruction of all the bonds which held society together, with the removal of all the restraints on vice or guilt, the fabric of civilisation and religion was speedily dissolved. To the licentious orgies of the Regent Orleans succeeded the infernal fury of the Revolution; from the same Palais Royal from whence had sprung those fountains of courtly corruption, soon issued forth the fiery streams of democracy. Enveloped in this burning torrent, the institutions, the faith, the nobles, the throne, were destroyed; the worst instruments of the Supreme Justice, the passions and ambition of men, were suffered to work their unresisted way; and in a few years the religion of eighteen centuries was abolished, its priests slain or exiled, its Sabbath abolished, its rites proscribed, its faith unknown. Infancy came into the world without a blessing, age left it without a hope; marriage no longer received a benediction, sickness was left without consolation; the village bell ceased to call the poor to their weekly day of sanctity and repose; the village churchyard to witness the weeping train of mourners attending their rude forefathers to their last home. The grass grew in the churches of every parish in France; the dead without a blessing were thrust into vast charnel-houses; marriage was contracted before a civil magistrate; and infancy, untaught to pronounce the name of God, longed only for the period when the passions and indulgences of life were to commence.

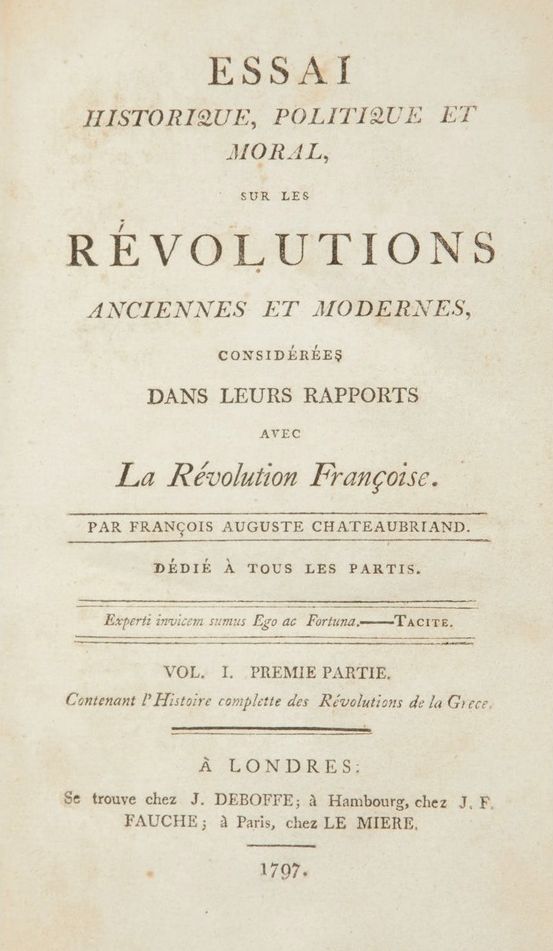

It was in these disastrous days that Chateaubriand arose, and bent the force of his lofty mind to restore the fallen but imperishable faith of his fathers. In early youth, he was at first carried away by the fashionable infidelity of his times; and in his Essais Historiques, which he published in 1792 in London, while the principles of virtue and natural religion are unceasingly maintained, he seems to have doubted whether the Christian religion was not crumbling with the institutions of society, and speculated what faith was to be established on its ruins. But misfortune, that great corrector of the vices of the world, soon changed these faulty views. In the days of exile and adversity, when by the waters of Babylon he sat down and wept, he reverted to the faith and the belief of his fathers, and inhaled in the school of adversity those noble maxims of devotion and duty which have ever since regulated his conduct in life. Undaunted, though alone, he placed himself on the ruins of the Christian faith; renewed, with Herculean strength, a contest which the talents and vices of half a century had to all appearance rendered hopeless; and, speaking to the hearts of men, now purified by suffering, and cleansed by the agonising ordeal of revolution, scattered far and wide the seeds of a rational and manly piety. Other writers have followed in the same noble career: Salvandy and Guizot have traced the beneficial effects of religion upon modern society, and drawn from the last results of revolutionary experience just and sublime conclusions as to the adaptation of Christianity to the wants of humanity; but it is the glory of Chateaubriand to have come forth alone the foremost in the fight; to have planted himself on the breach, when it was strewed only with the dying and dead, and, strong in the consciousness of gigantic powers, stood undismayed against a nation in arms.

To be successful in the contest, it was indispensable that the weapons of warfare should be totally changed. When the ideas of men were set adrift by revolutionary changes, when the authority of ages was set at naught, and from centuries of experience appeals were made to weeks of innovation, it was in vain to refer to the great or the wise of former ages. Perceiving at once the immense change that had taken place in the world which he addressed, Chateaubriand saw that he must alter altogether the means by which it was to be influenced. Disregarding, therefore, entirely the weight of authority, laying aside almost everything which had been advanced in support of religion by its professed disciples, he applied himself to accumulate the conclusions in its favour which arose from its internal beauty; from its beneficent effect upon society; from the changes it had wrought upon the civilisation, the happiness, and destinies of mankind; from its analogy with the sublimest tenets of natural religion; from its unceasing progress, its indefinite extension, and undecaying youth. He observed that it drew its support from such hidden recesses of the human heart, that it flourished most in periods of disaster and calamity; derived strength from the fountains of suffering, and, banished in all but form from the palaces of princes, spread its roots far and wide in the cottages of the poor. From the intensity of suffering produced by the Revolution, therefore, he conceived the hope that the feelings of religion would ultimately resume their sway; when the waters of bitterness were let loose, the consolations of devotion would again be felt to be indispensable; and the spirit of the Gospel, banished during the sunshine of corrupt prosperity, return to the repentant human heart with the tears and the storms of adversity.

Proceeding on these just and sublime principles, this great author availed himself of every engine which fancy, experience, or poetry could suggest, to sway the hearts of his readers. He knew well that he was addressing an impassioned and volatile generation, upon whom reason would be thrown away, if not enforced with eloquence; and argument lost, if not clothed in the garb of fancy. To effect his purpose, therefore, of reopening in the hearts of his readers the all but extinguished fountains of religious feeling, he summoned to his aid all that learning, or travelling, or poetry, or fancy could supply; and scrupled not to employ his powers as a writer of romance, a historian, a descriptive traveller, and a poet, to forward the great work of Christian renovation. Of his object in doing this, he has himself given the following account:—

“There can be no doubt that the Genius of Christianity would have been a work entirely out of place in the age of Louis XIV; and the critic who observed that Massillon would never have published such a book, spoke an undoubted truth. Most certainly the author would never have thought of writing such a work if there had not existed a host of poems, romances, and books of all sorts, where Christianity was exposed to every species of derision. But since these poems, romances, and books exist, and are in every one’s hands, it becomes indispensable to extricate religion from the sarcasms of impiety; when it has been written on all sides that Christianity is barbarous, ridiculous, the eternal enemy of the arts and of genius;‘ it is necessary to prove that it is neither barbarous, nor ridiculous, nor the enemy of arts or of genius; and that that which is made by the pen of ridicule to appear diminutive, ignoble, in bad taste, without either charms or tenderness, may be made to appear grand, noble, simple, impressive, and divine, in the hands of a man of religious feeling.

“If it is not permitted to defend religion on what may be called its terrestrial side, if no effort is to be made to prevent ridicule from attaching to its sublime institutions, there will always remain a weak and undefended quarter. There all the strokes at it will be aimed; there you will be caught without defence; from thence you will receive your death-wound. Is not that what has already arrived? Was it not by ridicule and pleasantry that Voltaire succeeded in shaking the foundations of faith? Will you attempt to answer by theological arguments, or the forms of the syllogism, licentious novels or irreligious epigrams? Will formal disquisitions ever prevent an infidel generation from being carried away by clever verses, or deterred from the altar by the fear of ridicule? Does not every one know that in the French nation a happy bon-mot, impiety clothed in a felicitous expression, a felix culpa, produce a greater effect than volumes of reasoning or metaphysics? Persuade young men that an honest man can be a Christian without being a fool; convince him that he is in error when he believes that none but capuchins and old women believe in religion, and your cause is gained it will be time enough, to complete the victory, to present yourself armed with theological reasons; but what you must begin with is, an inducement to read your book. What is most needed is a popular work on religion. Those who have hitherto written on it have too often fallen into the error of the traveller who tries to get his companion at one ascent to the summit of a rugged mountain when he can hardly crawl at its foot: you must show him at every step varied and agreeable objects; allow him to stop to gather the flowers which are scattered along his path; and from one resting-place to another he will at length gain the summit.

“The author has not intended this work merely for scholars, priests, or doctors; what he wrote for was the men of the world, and what he aimed at chiefly were the considerations calculated to affect their minds. If you do not keep steadily in view that principle, if you forget for a moment the class of readers for whom the Genius of Christianity was intended, you will understand nothing of this work. It was intended to be read by the most incredulous man of letters, the most volatile youth of pleasure, with the same facility as the first turns over a work of impiety, or the second devours a corrupting novel. Do you intend then, exclaim the well-meaning advocates for Christianity, to render religion a matter of fashion? Would to God, I reply, that that divine religion was really in fashion, in the sense that what is fashionable indicates the prevailing opinion of the world! Individual hypocrisy, indeed, might be increased by such a change, but public morality would unquestionably be a gainer. The rich would no longer make it a point of vanity to corrupt the poor, the master to pervert the mind of his domestic, the fathers of families to pour lessons of atheism into their children: the practice of piety would lead to a belief in its truths, and with the devotion we should see revive the manners and the virtues of the best ages of the world.

“Voltaire, when he attacked Christianity, knew mankind well enough not to seek to avail himself of what is called the opinion of the world, and with that view he employed his talents to bring impiety into fashion. He succeeded by rendering religion ridiculous in the eyes of a frivolous generation. It is this ridicule which the author of the Genius of Christianity has, beyond everything, sought to efface; that was the object of his work. He may have failed in the execution, but the object surely was highly important. To consider Christianity in its relation with human society; to trace the changes which it has effected in the reason and the passions of man; to show how it has modified the genius of arts and of letters, moulded the spirit of modern nations; in a word, to unfold all the marvels which religion has wrought in the regions of poetry, morality, politics, history, and public charity, must always be esteemed a noble undertaking. As to its execution, he abandons himself, with submission, to the criticisms of those who appreciate the spirit of the design.

“Take, for example, a picture, professedly of an impious tendency, and place beside it another picture on the same subject from the Genius of Christianity, and I will venture to affirm that the latter picture, however feebly executed, will weaken the impression of the first; so powerful is the effect of simple truth when compared to the most brilliant sophisms. Voltaire has frequently turned the religious orders into ridicule: well, put beside one of his burlesque representations the chapter on the Missions, that where the order of the Hospitallers is depicted as succouring the travellers in the desert; or the monks relieving the sick in the hospitals, attending those dying of the plague in the lazarettos, or accompanying the criminal to the scaffold,—what irony will not be disarmed? what malicious smile will not be converted into tears? Answer the reproaches made to the worship of the Christians for their ignorance, by appealing to the immense labours of the ecclesiastics who saved from destruction the manuscripts of antiquity. Reply to the accusations of bad taste and barbarity, by referring to the works of Bossuet and Fenelon. Oppose to the caricatures of saints and of angels, the sublime effects of Christianity on the dramatic part of poetry, on eloquence, and the fine arts, and say whether the impression of ridicule will long maintain its ground! Should the author have no other success than that of having displayed before the eyes of an infidel age a long series of religious pictures without exciting disgust, he would deem his labours not useless to the cause of humanity.”—Vol. iii. 263, 266.

These observations appear to us as just as they are profound; and they are the reflections not merely of a sincere Christian, but of a man practically acquainted with the state of the world. It is of the utmost importance, no doubt, that there should exist works on the Christian faith, in which the arguments of the sceptic should be combated, and to which the Christian disciple might refer with confidence for a refutation of the objections which have been urged against his religion. But great as is the merit of such productions, their beneficial effects are limited in their operation compared with those which are produced by such writings as we are considering. The hardened sceptic will never turn to a work on divinity for a solution of his paradoxes; and men of the world can never be persuaded to enter on serious arguments even on the most momentous subject of human belief. It is the indifference, not the scepticism of such men, which is chiefly to be dreaded: the danger to be apprehended is not that they will say there is no God, but that they will live altogether without God in the world. It has happened but too frequently that divines, in their zeal for the progress of Christianity among such men, have augmented the very evil they intended to remove. They have addressed themselves in general to them as if they were combatants drawn out in a theological dispute; they have urged a mass of arguments which they were unable to refute, but which were too uninteresting to be even examined; and while they flattered themselves that they had effectually silenced their opponents’ objections, those whom they addressed have silently passed by on the other side. It is, therefore, of incalculable importance that some writings should exist which should lead men imperceptibly into the ways of truth, which should insinuate themselves into the tastes, and blend themselves with the refinements of ordinary life, and perpetually recur to the cultivated mind with all that it admires, or loves, or venerates, in the world.

Nor let it be imagined that reflections such as these are not the appropriate theme of religious instruction—that they do not form the fit theme of Christian meditation. Whatever leads our minds habitually to the Author of the Universe; whatever mingles the voice of nature with the revelation of the Gospel; whatever teaches us to see, in all the changes of the world the varied goodness of Him in whom we live, and move, and have our being,” brings us nearer to the spirit of the Saviour of mankind. But it is not only as encouraging a sincere devotion, that these reflections are favourable to Christianity; there is something, moreover, peculiarly allied to its spirit in such observations of external nature. When our Saviour prepared himself for his temptation, his agony, and death, he retired to the wilderness of Judæa, to inhale, we may venture to believe, a holier spirit amidst its solitary scenes, and to approach to a nearer communion with his Father, amidst the sublimest of his works. It is with similar feelings, and to worship the same Father, that the Christian is permitted to enter the temple of nature; and by the spirit of his religion, there is a language infused into the objects which she presents, unknown to the worshipper of former times. To all indeed the same objects appear the same sun shines the same heavens are open, but to the Christian alone it is permitted to know the author of these things; to see His spirit “move in the breeze and blossom in the spring;” and to read, in the changes which occur in the material world, the varied expression of eternal love. It is from the influence of Christianity accordingly that the key has been given to the signs of nature. It was only when the Spirit of God moved on the face of the deep, that order and beauty were seen in the world.

It is accordingly peculiarly well worthy of observation, that the beauty of nature, as felt in modern times, seems to have been almost unknown to the writers of antiquity. They described occasionally the scenes in which they dwelt; but, if we except Virgil, whose gentle mind seems to have anticipated, in this instance, the influence of the Gospel, never with any deep Feeling of their beauty. Then, as now, the citadel of Athens looked upon the evening sun, and her temples flamed in his setting beam; but what Athenian writer ever described the matchless glories of the scene? Then, as now, the silvery clouds of the Ægean sea rolled round her verdant isles, and sported in the azure vault of heaven; but what Grecian poet has been inspired by the sight? The Italian lakes spread their waves beneath a cloudless sky, and all that is lovely in nature was gathered around them; yet even Eustace tells us, that a few detached lines is all that is left in regard to them by the Roman poets. The Alps themselves,

“The palaces of nature, whose vast walls

Have pinnacled in clouds their snowy scalps,

And throned eternity in icy halls

Of cold sublimity, where forms and falls

The avalanche—the thunderbolt of snow,—”

Even these, the most glorious objects which the eye of man can behold, were regarded by the ancients with sentiments only of dismay or horror; as a barrier from hostile nations, or as the dwelling of barbarous tribes. The torch of religion had not then lightened the face of nature; they knew not the language which she spoke, nor felt that holy spirit which to the Christian gives the sublimity of these scenes.

Chateaubriand divides his great work into four parts. The first treats of the doctrinal parts of religion; the second and the third, of the relations of that religion with poetry, literature, and the arts; the fourth, of the ceremonies of public worship, and the services rendered to mankind by the clergy, regular and secular. On the mysteries of faith he commences with these fine observations:

“There is nothing beautiful, sweet, or grand in life, but has its mystery. The sentiments which agitate us most strongly are enveloped in obscurity; modesty, virtuous love, sincere friendship, have all their secrets, with which the world must not be made acquainted. Hearts which love understand each other by a word; half of each is at all times open to the other. Innocence itself is but a holy ignorance, and the most ineffable of mysteries. Infancy is only happy because it as yet knows nothing; age miserable because it has nothing more to learn. Happily for it, when the mysterics of life are ending, those of immortality commence.

“If it is thus with the sentiments, it is assuredly not less so with the virtues; the most angelic are those which, emanating directly from the Deity, such as charity, love to withdraw themselves from all regards, as if fearful to betray their celestial origin.

“If we turn to the understanding, we shall find that the pleasures of thought also have a certain connexion with the mysterious. To what sciences do we unceasingly return ? To those which always leave something still to be discovered, and fix our regards on a perspective which is never to terminate. If we wander in the desert, a sort of instinct leads us to shun the plains where the eye embraces at once the whole circumference of nature, to plunge into forests, those forests the cradle of religion, whose shades and solitudes are filled with the recollections of prodigies, where the ravens and the doves nourished the prophets and fathers of the church. If we visit a modern monument, whose origin or destination is known, it excites no attention; but if we meet on a desert isle, in the midst of the ocean, with a mutilated statue pointing to the west, with its pedestal covered with hieroglyphics, and worn by the winds, what a subject of meditation is presented to the traveller! Everything is concealed, everything is hidden in the universe. Man himself is the greatest mystery of the whole. Whence comes the spark which we call existence, and in what obscurity is it to be extinguished? The Eternal has placed our birth and our death under the form of two veiled phantoms, at the two extremities of our career; the one produces the inconceivable gift of life, which the other is ever ready to devour.

“It is not surprising, then, considering the passion of the human mind for the mysterious, that the religions of every country should have had their impenetrable secrets. God forbid that I should compare their mysteries to those of the true faith, or the unfathomable depths of the Sovereign in the heavens, to the changing obscurities of those gods which are the work of human hands. All that I observe is, that there is no religion without mysteries, and that it is they with the sacrifice which everywhere constitute the essence of the worship. God is the great secret of nature: the Deity was veiled in Egypt, and the Sphynx was seated at the entrance of his temples.”—Vol. i. 13, 14.

On the three great sacraments of the Church—Baptism, Confession, and the Communion—he makes the following beautiful observations:

“Baptism, the first of the sacraments which religion confers upon man, clothes him, in the words of the Apostle, with Jesus Christ. That sacrament reveals at once the corruption in which we were born, the agonising pains which attended our birth, and the tribulations which follow us into the world; it tells us that our faults will descend upon our children, and that we are all jointly responsible-a terrible truth, which, if duly considered, would alone suffice to render the reign of virtue universal in the world.

“Behold the infant in the midst of the waters of the Jordan! The Man of the Wilderness pours the purifying stream on his head; the river of the Patriarchs, the camels on its banks, the Temple of Jerusalem, the cedars of Lebanon, seem to regard with interest the mighty spectacle. Behold in mortal life that infant near the sacred fountain; a family filled with thankfulness surround it; renounce in its name the sins of the world; bestow on it with joy the name of its grandfather, which seems thus to become immortal, in its perpetual renovation by the fruits of love from generation to generation. Even now the father is impatient to take his infant in his arms, to replace it in its mother’s bosom, who listens behind the curtains to all the thrilling sounds of the sacred ceremony. The whole family surround the maternal bed; tears of joy, mingled with the transports of religion, fall from every eye; the new name of the infant, the old name of its ancestor, is repeated by every mouth, and every one mingling the recollections of the past with the joys of the present, thinks that he sees the venerable grandfather revive in the new-born which has taken his name. Such is the domestic spectacle which throughout all the Christian world the sacrament of Baptism presents; but religion, ever mingling lessons of duty with scenes of joy, shows us the son of kings clothed in purple, renouncing the grandeur of the world, at the same fountain where the child of the poor in rags abjures the pomps by which he will in all probability never be tempted.

“Confession follows baptism; and the Church, with that wisdom which it alone possesses, fixed the era of its commencement at that period when first the idea of crime can enter the infant mind-that is, at seven years of age. All men, including the philosophers, how different soever their opinions may be on other subjects, have regarded the sacrament of penitence as one of the strongest barriers against crime, and a chef-d’œuvre of wisdom. What innumerable restitutions and reparations, says Rousseau, has confession caused to be made in Catholic countries! According to Voltaire, ‘Confession is an admirable invention, a bridle to crime, discovered in the most remote antiquity, for confession was recognised in the celebration of all the ancient mysteries. We have adopted and sanctified that wise custom, and its effects have always been found to be admirable in inclining hearts, ulcerated by hatred, to forgiveness.’

“But for that salutary institution, the guilty would give way to despair. In what bosom would he discharge the weight of his heart? In that of a friend-Who can trust the friendship of the world? Shall he take the deserts for a confident? Alas! the deserts are ever filled to the ear of crime with those trumpets which the parricide Nero heard round the tomb of his mother. When men and nature are unpitiable, it is indeed consolatory to find a Deity inclined to pardon; but it belongs only to the Christian religion to have made twin sisters of Innocence and Repentance.

“In fine, the Communion presents instructive ceremony. It teaches morality, for we must be pure to approach it; it is the offering of the fruits of the earth to the Creator, and it recalls the sublime and touching history of the Son of Man. Blended with the recollection of Easter, and of the first covenant of God with man, the origin of the communion is lost in the obscurity of an infant world; it is related to our first ideas of religion and society, and recalls the pristine equality of the human race; in fine, it perpetuates the recollection of our primeval fall, of our redemption, and reacceptance by God.”—Vol. i. 30-46.

These and similar passages, not merely in this work, which professes to be of a popular cast, but in others of the highest class of Catholic divinity, suggest an idea which, the more we extend our reading, the more we shall find to be just-viz., that in the greater and purer writers on religion, of whatever church or age, the leading doctrines are nearly the same, and that the differences which divide their followers, and distract the world, are seldom, on any material or important points, to be met with in writers of a superior caste. Chateaubriand is a faithful, and in some respects, perhaps, a bigoted Catholic; yet there is hardly a word here, or in any other part of his writings on religion, to which a Christian in any country may not subscribe, and which is not calculated in all ages and places to forward the great work of the purification and improvement of the human heart. Travellers have often observed that in a certain rank in all countries manners are the same; naturalists know that at a certain elevation above the sea in all latitudes we meet with the same vegetable productions; and philosophers have often remarked, that, in the highest class of intellects, opinions on almost every subject in all ages and places are the same. A similar uniformity may be observed in the principles of the greatest writers of the world on religion; and while the inferior followers of their different tenets branch out into endless divisions, and indulge in sectarian rancour, in the more lofty regions of intellect the principles are substantially the same, and the objects of all identical. So small a proportion do all the disputed points in theology bear to the great objects of religion—love to God, charity to man, and the subjugation of human passion.

On the subject of marriage, and the reasons for its indissolubility, our author presents us with the following beautiful observations:—

“Habit and a long life together are more necessary to happiness, and even to love, than is generally imagined. No one is happy with the object of his attachment until he has passed many days, and above all, many days of misfortune, with her. The married pair must know each other to the bottom of their souls; the mysterious veil which covered the two spouses in the primitive church must be raised in its inmost folds, how closely soever it may be kept drawn to the rest of the world.

“What! on account of a fit of caprice, or a burst of passion, am I to be exposed to the fear of losing my wife and my children, and to renounce the hope of passing my declining days with them? Let no one imagine that fear will make me become a better husband. No; we do not attach ourselves to a possession of which we are not secure, we do not love a property which we are in danger of losing.

“We must not give to Hymen the wings of Love, nor make of a sacred reality a fleeting phantom. One thing is alone sufficient to destroy your happiness in such transient unions; you will constantly compare one to the other, the wife you have lost to the one you have gained; and, do not deceive yourself, the balance will always incline to the past, for so God has constructed the human heart. This distraction of a sentiment which should be indivisible will empoison all your joys. When you caress your new infant, you will think of the smiles of the one you have lost; when you press your wife to your bosom, your heart will tell you that she is not the first. Everything in man tends to unity; he is no longer happy when he is divided, and, like God, who made him in His image, his soul seeks incessantly to concentrate into one point the past, the present, and the future.

“The wife of a Christian is not a simple mortal: she is a mysterious angelic being the flesh of the flesh, the blood of the blood of her husband. Man, in uniting himself to her, does nothing but regain part of the substance which he has lost. His soul as well as his body are incomplete without his wife he has strength, she has beauty; he combats the enemy and labours the fields, but he understands nothing of domestic life; his companion is awanting to prepare his repast and sweeten his existence. He has his crosses, and the partner of his couch is there to soften them: his days may be sad and troubled, but in the chaste arms of his wife he finds comfort and repose. Without woman man would be rude, gross, and solitary. Woman spreads around him the flowers of existence, as the creepers of the forests which decorate the trunks of sturdy oaks with their perfumed garlands. Finally, the Christian pair live and die united: together they rear the fruits of their union; in the dust they lie side by side; and they are reunited beyond the limits of the tomb.”—Vol. i. 78, 79.

The extreme unction of the Catholic Church is described in these touching words:—

“Come and behold the most moving spectacle which the world can exhibit the death of the faithful. The dying Christian is no longer a man of this world; he belongs no farther to his country; all his relations with society have ceased. For him the calculations of time are closed, and the great era of eternity has commenced. A priest seated beside his bed pours the consolations of religion into his dying ear: the holy minister converses with the expiring penitent on the immortality of the soul; and that sublime scene which antiquity presented but once in the death of the greatest of her philosophers, is renewed every day at the couch where the humblest Christian expires.

“At length the supreme moment arrives: one sacrament has opened the gates of the world, another is about to close them; religion rocked the cradle of existence; its sweet strains and its maternal hand will lull it to sleep in the arms of death. It prepares the baptism of a second existence; but it is no longer with water, but oil, the emblem of celestial incorruption. The liberating sacrament dissolves, one by one, the chords which attach the faithful to this world: the soul, half escaped from its earthly prison, is almost visible to the senses, in the smile which plays around his lips. Already he hears the music of the seraphim; already he longs to fly to those regions, where hope divine, daughter of virtue and death, beckons him to approach. At length the angel of peace, descending from the heavens, touches with his golden sceptre his wearied eyelids, and closes them in delicious repose to the light. He dies; and so sweet has been his departure, that no one has heard his last sigh; and his friends, long after he is no more, preserve silence round his couch, still thinking that he slept: so like the sleep of infancy is the death of the just.”—Vol. i. 69, 71.

It is against pride, as every one knows, that the chief efforts of the Catholic Church have always been directed, because they consider it as the source of all other crime. Whether this is a just view may, perhaps, be doubted, to the extent at least to which they carry it; but there can be but one opinion as to the eloquence of the apology which Chateaubriand makes for this selection.

“In the virtues preferred by Christianity, we perceive the same knowledge of human nature. Before the coming of Christ, the soul of man was a chaos; but no sooner was the Word heard, than all the elements arranged themselves in the moral world, as, at the same divine inspiration they had produced the marvels of material creation. The virtues ascended like pure fires into the heavens; some, like brilliant suns, attracted the regards by their resplendent light; others, more modest, sought the shade, where nevertheless their lustre could not be concealed. From that moment an admirable balance was established between the forces and the weaknesses of existence. Religion directed its thunders against pride, the vice which is nourished by the virtues; it discovers it in the inmost recesses of the heart, and follows it out in all its metamorphoses; the sacraments in a holy legion march against it, while humility, clothed in sackcloth and ashes, its eyes downcast and bathed in tears, becomes one of the chief virtues of the faithful.”—Vol. i. 74.

On the tendency of all the fables concerning creation to remount to one general and eternal truth, our author presents the following reflections:

“After this exposition of the dreams of philosophy, it may seem useless to speak of the fancy of the poets. Who does not know Deucalion and Pyrrha, the age of gold and of iron? What innumerable traditions are scattered through the earth! In India, an elephant sustains the globe; the sun in Peru has brought forth all the marvels of existence; in Canada, the Great Spirit is the father of the world; in Greenland, man has emerged from an egg; in fine, Scandinavia has beheld the birth of Askur and Emla; Odin has poured in the breath of life, Hœnerus reason, and Loedur blood and beauty.

‘Askum et Emlam omni conatu destitutos

Animam nec possidebant, rationem nec habebant

Nec sanguinem, nec sermonem, nec faciem venustam.

Animam dedit Odinus, rationem dedit Hœnerus,

Loedur sanguinem addidit et faciem venustam.’

“In these various traditions, we find ourselves placed between the stories of children and the abstractions of philosophers; if we were obliged to choose, it were better to take the first.

“But to discover the original of the picture in the midst of so many copies, we must recur to that which, by its unity and the perfection of its parts, unfolds the genius of a master. It is that which we find in Genesis, the original of all those pictures which we see reproduced in so many different traditions. What can be at once more natural and more magnificent more easy to conceive, and more in unison with human reason, than the Creator descending amidst the night of ages to create light by a word? In an instant, the sun is seen suspended in the heavens, in the midst of an immense azure vault; with invisible bonds he envelops the planets, and whirls them round his burning axle; the sea and the forests appear on the globe, and their earliest voices arise to announce to the universe that great marriage, of which God is the priest, the earth the nuptial couch, and the human race the posterity.”—Vol. i. 97, 98.

On the appearance of age on the globe, and its first aspect when fresh from the hands of the Creator, the author presents an hypothesis more in unison with the imagination of a poet than the observations of a philosopher, on the gradual formation of all objects destined for a long endurance. He supposes that everything was at once created as we now see it.

“It is probable that the Author of nature planted at once aged forests and their youthful progeny; that animals arose at the same time, some full of years, others buoyant with the vigour and adorned with the grace of youth. The oaks, while they pierced with their roots the fruitful earth, without doubt bore at once the old nests of rooks, and the young progeny of doves. At once grew a chrysalis and a butterfly; the insect bounded on the grass, suspended its golden egg in the forests, or trembled in the undulations of the air. The bee, which had not yet lived a morning, already counted the generations of flowers by its ambrosia-the sheep was not without its lamb, the doe without its fawns. The thicket already contained the nightingales, astonished at the melody of their first airs, as they poured forth the new-born effusion of their infant loves.

“Had the world not arisen at once young and old, the grand, the serious, the impressive would have disappeared from nature; for all these sentiments depend for their very essence on ancient things. The marvels of existence would have been unknown. The ruined rock would not have hung over the abyss beneath; the woods would not have exhibited that splendid variety of trunks bending under the weight of years, of trees hanging over the bed of streams. The inspired thoughts, the venerated sounds, the magic voices, the sacred horror of the forests, would have vanished with the vaults which serve for their retreats; and the solitudes of earth and heaven would have remained naked and disenchanted in losing the columns of oaks which united them. On the first day when the ocean dashed against the shore, he bathed, be assured, sands bearing all the marks of the action of his waves for ages; cliffs strewed with the eggs of innumerable sea-fowl, and rugged capes which sustained against the waters the crumbling shores of the earth.

“Without that primeval age, there would have been neither pomp nor majesty in the work of the Most High; and, contrary to all our conceptions, nature in the innocence of man would have been less beautiful than it is now in the days of his corruption. An insipid childhood of plants, of animals, of elements, would have covered the earth, without the poetical feelings which now constitute its principal charm. But God was not so feeble a designer of the grove of Eden as the incredulous would lead us to believe. Man, the sovereign of nature, was born at thirty years of age, in order that his powers should correspond with the full-grown magnificence of his new empire,while his consort, doubtless, had already passed her sixteenth spring, though yet in the slumber of nonentity, that she might be in harmony with the flowers, the birds, the innocence, the love, the beauty of the youthful part of the universe.”—Vol. i. 137, 138.

In the rhythm of prose, these are the colours of poetry; but still this was not to all appearance the order of creation. And here, as in many other instances, it will be found that the deductions of experience present conclusions more sublime than the most fervid imagination has been able to conceive. Everything announces that the great works of nature are carried on by slow and insensible gradations; continents, the abode of millions, are formed by the confluence of innumerable rills; vegetation, commencing with the lichen and the moss, rises at length into the riches and magnificence of the forest. Patient analysis, philosophical discovery, have now taught us that it was by the same slow progress that the great work of creation was accomplished. The fossil remains of antediluvian ages have laid open the primeval works of nature; the long period which elapsed before the creation of man, the vegetables which then covered the earth, the animals which sported amidst its watery wastes, the life which first succeeded to chaos, all stand revealed. To the astonishment of mankind, the order of creation, unfolded in Genesis, is proved by the contents of the earth beneath every part of its surface to be precisely that which has actually been followed; the days of the Creator’s workmanship turn out to be the days of the Most High, not of His uncreated subjects, and to correspond to ages of our ephemeral existence; and the great sabbath of the earth took place, not, as we imagined, when the sixth sun had set after the first morning had beamed, but when the sixth period had expired, devoted by Omnipotence to the mighty undertaking. God then rested from his labours, because the great changes of matter, and the successive production and annihilation of different kinds of animated existence, ceased; creation assumed a settled form, and laws came into operation destined for indefinite endurance. Chateaubriand said truly, that to man, when he first opened his eyes on paradise, nature appeared with all the majesty of age as well as all the freshness of youth; but it was not in a week, but during a series of ages, that the magnificent spectacle had been assembled; and for the undying delight of his progeny, in all future years, the powers of nature for countless time had been already exerted.

The fifth book of the Génie du Christianisme treats of the proofs of the existence of God, derived from the wonders of material nature; in other words, of the splendid subject of natural theology. On such a subject, the observations of a mind so stored with knowledge, and gifted with such powers of eloquence, may be expected to be something of extraordinary excellence. Though the part of his work, accordingly, which treats of this subject, is necessarily circumscribed, from the multitude of others with which it is overwhelmed, it is of surpassing beauty, and superior in point of description to anything which has been produced on the same subject by the genius of Britain.

“There is a God! The herbs of the valley, the cedars of the mountain, bless Him-the insect sports in His beams-the elephant salutes Him with the rising orb of the day-the bird sings Him in the foliage-the thunder proclaims Him in the heavens-the ocean declares His immensity-man alone has said, There is no God!’

“Unite in thought, at the same instant, the most beautiful objects in nature; suppose that you see at once all the hours of the day, and all the seasons of the year; a morning of spring and a morning of autumn; a night bespangled with stars, and a night covered with clouds; meadows enamelled with flowers, forests hoary with snow; fields gilded by the tints of autumn; then alone you will have a just conception of the universe. While you are gazing on that sun which is plunging under the vault of the west, another observer admires him emerging from the gilded gates of the East. By what unconceivable magic does that aged star, which is sinking fatigued and burning in the shades of the evening, reappear at the same instant fresh and humid with the rosy dew of the morning? At every instant of the day the glorious orb is at once rising-resplendent at noonday, and setting in the west; or rather our senses deceive us, and there is, properly speaking, no east, or south, or west in the world. Everything reduces itself to one single point, from whence the King of Day sends forth at once a triple light in one single substance. The bright splendour is perhaps that which nature can present that is most beautiful; for while it gives us an idea of the perpetual magnificence and resistless power of God, it exhibits, at the same time, a shining image of the glorious Trinity.”

The instincts of animals, and their adaptation to the wants of their existence, have long furnished one of the most interesting subjects of study to the naturalist, and of meditation to the devout observer of creation. Chateaubriand has painted, with his usual descriptive powers, one of the most familiar of these examples-

“What ingenious springs move the feet of a bird? It is not by a contraction of muscles dependent on his will that he maintains himself firm upon a branch; his foot is constructed in such a way that when it is pressed in the centre, the toes close of their own accord upon the body which supports it. It results from this mechanism, that the talons of the bird grasp more or less firmly the object on which it has alighted, in proportion to the agitation, more or less violent, which it has received. Thus, when we see at the approach of night, during winter, the crows perched on the scathed summit of an aged oak, we suppose that, watchful and attentive, they maintain their place with pain during the rocking of the winds; and yet, heedless of danger, and mocking the tempest, the winds only bring them profounder slumber. The blasts of the north attach them more firmly to the branch, from whence we every instant expect to see them precipitated; and like the old seaman, whose hammock is suspended to the roof of his vessel, the more he is tossed by the winds, the more profound is his repose.”—Vol. i. 147, 148.

“Amidst the different instincts which the Sovereign of the universe has implanted in nature, one of the most wonderful is that which every year brings the fish of the Pole to our temperate region. They come, without once mistaking their way, through the solitude of the ocean, to reach, on a fixed day, the stream where their hymen is to be celebrated. The spring prepares on our shores their nuptial pomp; it covers the billows with verdure, it spreads beds of moss in the waves to serve for curtains to its crystal couches. Hardly are these preparations completed when the enamelled legions appear; the animated navigators enliven our coasts; some spring aloft from the surface of the waters, others balance themselves on the waves, or diverge from a common centre like innumerable flashes of gold; these dart obliquely their shining bodies athwart the azure fluid, while others sleep in the rays of the sun, which penetrates beneath the dancing surface of the waves. All, sporting in the joys of existence, meander, return, wheel about, dash across, form in squadron, separate, and reunite; and the inhabitant of the seas, inspired by a breath of existence, pursues with bounding movements its mate, by the line of fire which is reflected from her in the stream.”—Vol. i. 152, 153.

Chateaubriand’s mind is full not only of the images, but the sounds, which attest the reign of animated nature. Equally familiar with those of the desert and of the cultivated plain, he has had his susceptibility alike open in both to the impressions which arise to a pious observer from their contemplation.

“There is a law in nature relative to the cries of animals, which has not been sufficiently observed, and deserves to be so. The different sounds of the inhabitants of the desert are calculated according to the grandeur or the sweetness of the scene where they arise, and the hour of the day when they are heard. The roaring of the lion, loud, rough, and tremendous, is in unison with the desert scenes in which it is heard; while the lowing of the oxen diffuses a pleasing calm through our valleys. The goat has something trembling and savage in its cry, like the rocks and ravines from which it loves to suspend itself. The war-horse imitates the notes of the trumpet that animates him to the charge, and, as if he felt that he was not made for degrading employments, he is silent under the spur of the labourer, and neighs under the rein of the warrior. The night, by turns charming or sombre, is enlivened by the nightingale or saddened by the owl; the one sings for the zephyrs, the groves, the moon, the soul of lovers-the other for the winds, the forests, the darkness, and the dead. Finally, all the animals which live on others have a peculiar cry by which they may be distinguished by the creatures which are destined to be their prey.”—Vol. i. 156.

The making of birds’ nests is one of the most common objects of observation. Listen to the reflections of genius and poetry on this beautiful subject.

“The admirable wisdom of Providence is nowhere more conspicuous than in the nests of birds. It is impossible to contemplate, without emotion, the Divine goodness, which thus gives industry to the weak and foresight to the thoughtless.

“No sooner have the trees put forth their leaves, than a thousand little workmen commence their labours. Some bring long pieces of straw into the hole of an old wall, others affix their edifice to the windows of a church; these steal a hair from the mane of a horse; those bear away, with wings trembling beneath its weight, the fragment of wool which a lamb has left entangled in the briers. A thousand palaces at once arise, and every palace is a nest within every nest is soon to be seen a charming metamorphosis; first, a beautiful egg, then a little one covered with down. The little nestling soon feels his wings begin to grow; his mother teaches him to raise himself on his bed of repose. Soon he takes courage enough to approach the edge of the nest, and casts a first look on the works of nature. Terrified and enchanted at the sight, he precipitates himself amidst his brothers and sisters, who have never as yet seen that spectacle; but, recalled a second time from his couch, the young king of the air, who still has the crown of infancy on his head, ventures to contemplate the boundless heavens, the waving summit of the pine-trees, and the vast labyrinth of foliage which lies beneath his feet. And, at the moment that the forests are rejoicing at the sight of their new inmate, an aged bird, who feels himself abandoned by his wings, quietly rests beside a stream: there, resigned and solitary, he tranquilly awaits death, on the banks of the same river where he sang his first loves, and whose trees still bear his nest and his melodious offspring.”—Vol. i. 158.

The subject of the migration of the feathered tribes furnishes this attentive observer of nature with many beautiful images. We have room only for the following extract:—

“In the first ages of the world, it was by the flowering of plants, the fall of the leaves, the departure and the arrival of birds, that the labourers and the shepherds regulated their labours. Thence has sprung the art of divination among certain people: they imagined that the birds which were sure to precede certain changes of the season or atmosphere, could not but be inspired by the Deity. The ancient naturalists, and the poets, to whom we are indebted for the few remains of simplicity which still linger amongst us, show us how marvellous was that manner of counting by the changes of nature, and what a charm it spread over the whole of existence. God is a profound secret. Man, created in his image, is equally incomprehensible. It was, therefore, an ineffable harmony to see the periods of his existence regulated by measures of time as harmonious as himself.

“Beneath the tents of Jacob or of Boaz, the arrival of a bird put everything in movement; the Patriarch made the circuit of the camp at the head of his followers, armed with scythes. If the report was spread that the young of the swallows had been seen wheeling about, the whole people joyfully commenced their harvest. These beautiful signs, while they directed the labours of the present, had the advantage of foretelling the vicissitudes of the approaching season. If the geese and swans arrived in abundance, it was known that the winter would be severe; did the redbreast begin to build its nest in January, the shepherds hoped in April for the roses of May. The marriage of a virgin on the margin of a fountain was represented by the first opening of the bud of the rose; and the death of the aged, who usually drop off in autumn, by the falling of leaves, or the maturity of the harvests. While the philosopher, abridging or elongating the year, extended the winter over the verdure of spring, the peasant felt no alarm that the astronomer, who came to him from heaven, would be wrong in his calculations. He knew that the nightingale would not take the season of hoarfrost for that of flowers, or make the groves resound at the winter solstice with the songs of summer. Thus the cares, the joys, the pleasures, of the rural life were determined, not by the uncertain calendar of the learned, but by the infallible signs of Him who traced his path to the sun. That sovereign Regulator wished Himself that the rites of His worship should be determined by the epochs fixed by His works; and in those days of innocence, according to the seasons and the labours they required, it was the voice of the zephyr or the tempest, of the eagle or the dove, which called the worshipper to the temple of his Creator.”—Vol. i. 171.

Let no one exclaim, What have these descriptions to do with the spirit of Christianity? Gray thought otherwise when he wrote the sublime lines on visiting the Grande Chartreuse; Buchanan thought otherwise, when, in his exquisite Ode to May, he supposed the first zephyrs of spring to blow over the Islands of the Just. The work of Chateaubriand, it is to be recollected, is not merely an exposition of the doctrines, spirit, or precepts of Christianity; it is intended expressly to allure, by the charms which it exhibits, the man of the world, an unbelieving and volatile generation, to the feelings of devotion; it is meant to combine all that is delightful or lovely in the works of nature, with all that is sublime or elevating in the revelations of religion. In his eloquent pages, therefore, we find united the Natural Theology of Paley, the Contemplations of Taylor, and the Analogy of Butler; and if the theologians will look in vain for the weighty arguments by which the English divines have established the foundation of their faith, men of ordinary education will find even more to entrance and subdue their minds.

Among the proofs of the immortality of the soul, our author, with all others who have thought upon the subject, classes the obvious disproportion between the desires and capacity of the soul, and the limits of its acquisitions and enjoyments in this world. In the following passage, this argument is placed in its just colours:—

“If it is impossible to deny that the hope of man continues to the edge of the grave; if it be true that the advantages of this world, so far from satisfying our wishes, tend only to augment the want which the soul experiences, and dig deeper the abyss which it contains within itself, we must conclude that there is something beyond the limits of time. Vincula hujus mundi,’ says St Augustin, asperitatem habent veram, jucunditatem falsam, certum dolorem, incertam voluptatem, durum laborem, timidam quietem, rem plenam miseriæ, spem beatitudinis inanem.’ Far from lamenting that the desire for felicity has been planted in this world, and its ultimate gratification only in another, let us discern in that only an additional proof of the goodness of God. Since sooner or later we must quit this world, Providence has placed beyond its limits a charm, which is felt as an attraction to diminish the terrors of the tomb; as a kind mother, when wishing to make her infant cross a barrier, places some agreeable object on the other side.”—Vol. i. 210.

“Finally, there is another proof of the immortality of the soul, which has not been sufficiently insisted on, and that is the universal veneration of mankind for the tomb. There, by an invincible charm, life is attached to death; there the human race declares itself superior to the rest of creation, and proclaims aloud its lofty destinies. What animal regards its coffin, or disquiets itself about the ashes of its fathers? Which one has any regard for the bones of its father, or even knows its father, after the first necessities of infancy are passed? Whence comes, then, the allpowerful idea which we entertain of death? Do a few grains of dust merit so much consideration? No; without doubt we respect the bones of our fathers, because an inward voice tells us that all is not lost with them; and that is the voice which has everywhere consecrated the funeral service throughout the world; all are equally persuaded that the sleep is not eternal, even in the tomb, and that death itself is but a glorious transfiguration.”—Vol. i. 217.

To the objection, that if the idea of God is innate, it must appear in children without any education, which is not generally the case, Chateaubriand replies:—

“God being a spirit, and it being impossible that he should be understood but by a spirit, an infant, in whom the powers of thought are not as yet developed, cannot form a proper conception of the Supreme Being. We must not expect from the heart its noblest function, when the marvellous fabric is as yet in the hands of its Creator.

“Besides, there seems reason to believe that a child has at least a sort of instinct of its Creator; witness only its little reveries, its disquietudes, its fears in the night, its disposition to raise its eyes to heaven. An infant joins together its little hands, and repeats after its mother a prayer to the good God. Why does that little angel lisp with so much love and purity the name of the Supreme Being, if it has no inward consciousness of His existence in its heart?

“Behold that new-born infant, which the nurse still carries in her arms. What has it done to give so much joy to that old man, to that man in the prime of life, to that woman? Two or three syllables half-formed, which no one rightly understands, and instantly three reasonable creatures are transported with delight, from the grandfather, to whom all that life contains is known, to the young mother, to whom the greater part of it is as yet unrevealed. Who has put that power into the word of man? How does it happen that the sound of a human voice subjugates so instantaneously the human heart? What subjugates you is something allied to a mystery, which depends on causes more elevated than the interest, how strong soever, which you take in that infant; something tells you that these inarticulate words are the first openings of an immortal soul.”—Vol. i. 224.

There is a subject on which human genius can hardly dare to touch, the future felicity of the just. Our author thus treats this delicate subject:—

“The purest of sentiments in this world is admiration; but every earthly admiration is mingled with weakness, either in the object it admires or in that admiring. Imagine, then, a perfect being, which perceives at once all that is, and has, and will be; suppose that soul exempt from envy and all the weaknesses of life, incorruptible, indefatigable, unalterable; conceive it contemplating, without ceasing, the Most High, discovering incessantly new perfections; feeling existence only from the renewed sentiment of that admiration; conceive God as the sovereign beauty, the universal principle of love; figure all the attachments of earth blending in that abyss of feeling, without ceasing to love the objects of affection on this earth; imagine, finally, that the inmate of heaven has the conviction that this felicity is never to end, and you will have an idea, feeble and imperfect indeed, of the felicity of the just. They are plunged in this abyss of delight, as in an ocean from which they cannot emerge: they wish nothing; they have everything, though desiring nothing—an eternal youth, a felicity without end; a glory divine is expressed in their countenances; a sweet, noble, and majestic joy; it is a sublime feeling of truth and virtue which transports them; at every instant they experience the same rapture as a mother who regains a beloved child whom she believed lost; and that exquisite joy, too fleeting on earth, is there prolonged through the ages of eternity.”—Vol. i. 241.

We intended to have gone through, in this paper, the whole Génie du Christianisme, and we have only concluded the first volume, so prolific of beauty are its pages. We make no apology for the length of the quotations, which have so much extended the limits of this article; any observations would be inexcusable which should abridge passages of such transcendent beauty.

(Continue to Part 2)

___________________________________________

[1] Sir Walter Scott, at this period, was on his deathbed, and Chateaubriand imprisoned by order of Louis Philippe.