Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 5 of Chivalry, by F. Warre Cornish (published 1901). Original footnotes are abridged.

The conception of war as a contest of heavy cavalry clad in armour was based not only upon personal prowess, but on the prowess of gentlemen of coat-armour, trained in the daily practice for the lists, and owning no comradeship with the churl who fought on foot, or the yeoman who stung the enemy’s chivalry with his long-barbed shafts. This conception was fostered by the growth of the habit of holding tournaments. As these increased in frequency and magnificence, so did they become less in touch with the practical conduct and theoretical development of war. The tournament, which had been a training for soldiers, became a court pageant; the knights believed themselves to have the secret of warfare all the time that their place was being taken by infantry, archery, and gunnery, and even by paid men-at-arms. They did not perceive that the world would not now be witched with noble horsemanship: and the maintenance of tournaments, after the decline of chivalry as an engine of war, heightened the contrast between the noble rider and the ‘plebeian soldier’ who was taking his place.

To the parade of tournament, rather than to the art of war, belong those combats of champions, whether told of monstrous Philistines, of gigantic Etruscans and Gauls, or of Moorish and Saracen Campeadors, which fill the pages of ancient and mediaeval chronicles and romances.

If the general himself engaged in such an adventurous business, the battle might be lost: and as a general rule the general would give his soldiers the example of courage, not of foolhardiness. The feats of the Cid and Richard I were exceptional even among knights errant; and the individual captains, like Marlborough, Condé and Napoleon, must have known when the risk was worth running, and when they must control their natural eagerness.

Among these may be reckoned the contests of champions in lieu of general battle, which are found in all early narratives of war. In the Persian legend the twelve Rokhs or heroes (like Charlemagne’s ‘dosipeers‘) of whom Rustum was the Roland, meet twelve Turkish champions and decide the war, which from them was called ‘the war of the twelve Rokhs’. Edmund Ironside proposed to Cnut to decide the kingdom by eight champions: William of Normandy challenged Harold, and accepted a challenge from Geoffrey of Anjou; John sent a cartel to Lewis VII of France; Edward III, to Philip of Valois; Richard II, to Charles VI; Francis I, to Charles V: that such challenges were not often accepted throws no discredit upon the good faith of those who sent them; though, as was natural, they commonly came from the party who had least to lose. These challenges were partly the natural expression of the military spirit delighting in personal distinction, partly of the nature of an ordeal, on the principle that God would defend the right. But when the stakes were not so vast, personal challenges are often met with. We read in the histories how Taillefer the jougleur rode at Hastings before the Norman host, half Berserker, half troubadour, throwing his lance into the air and catching it as it fell, and singing the song of Roland, careless of the certain death to which he was riding. At the siege of Jerusalem, 1097, one of Duke Robert’s men attacked the city wall alone and was killed, no one following him. The Cid, the Challenger, el Campeador, calls out gigantic Moors to battle and vanquishes them. Peter the Hermit summons the Saracen lord of Antioch to send him forth three Paynim knights to fight against three Christian knights, and gets for answer from the sober-minded heathen that he will do no such thing, and cares neither for Peter nor for Christ. Another knight (at Cherbourg 1379) invited three champions, ‘the most amorous knights’ of the enemy, to fight with three amorous knights on his part, for the love of their ladies, much as Beaumains or Gareth in the Morte d’ Arthur kills or spares knight after knight, red, green, and black, to please Linet. At the battle of Cocherel (1364) an English knight left the ranks ‘pour demander à faire un coup de lance contre celui des Francois qui seroit assez brave pour entrer en lice avec luy.’ Rowland du Boy presented himself ‘pour luy prêter le coler,’ and had the best of it. At Bannockburn De Bohun ‘ burned before his monarch’s eye to do some deed of chivalry,’ and pricked forth alone against Robert Bruce as he rode along the Scottish lines. Bruce, one might think, need not have risked his kingdom in a passage of arms with a crazy Englishman. The Duke of Wellington would not have done so. But the Bruce was of his own time, not of ours, and rejoiced in meeting such odds, mounted as he was on ‘a sorry jennet.’

The partridge may the falcon mock,

If yon slight palfrey stand the shock.

Bruce was a better man-at-arms than De Bohun, and ‘gave his battleaxe the swing’ with such result as those know who have read Scott’s chivalrous poem.[1]

The lord of the Castle of Josselin in Brittany, (27 Mar. 1351) Messire Robert de Beaumanoir, ‘vaillant chevalier durement et du plus grand lignage de Bretagne’ (note the heraldic pride of the chronicler) called upon the captain of the town and Castle of Ploermel to send him forth one champion, two, or three, to joust with swords against other three for the love of their ladies. ‘No,’ said Brandebourg their captain, ‘our ladies will not that we adventure ourselves for the passing chance of a single joust. But if you will, choose you out 20 or 30 of your companions and let them fight in a fair field.’ So the sixty champions heard Mass, put on their harness, and went forth to the place of arms, twenty-five of each on foot and five on horseback. Then they fought, and many were killed on this side and the other, and at the last the English had the worst of it, and all who were not slain were made prisoners, and courteously ransomed when they were healed of their wounds. Froissart saw, sitting at King Charles’s table, one of the champions, a Breton knight called Yvain Charuelz; and ‘his visage was so cut and slashed that he showed well how hard the fighting had been.’ The Barons at Kenilworth in the ‘War of the Disinherited’ (1266) disdained to wait behind their defences, and kept the castle gates open in defiance of Prince Edward for ten months, thinking chivalry more glorious than warfare — from the morrow of St. John Baptist to the morrow of St. Thomas 1266.

We may not deride this childish pride and useless bravery. We do not laugh at the piper who goes on playing the pipes when he is sickening with the pain of the bullet in his ankle, nor at the two drummer-boys of the Fore and Aft. Such incidents glorify war. We feel that the game of war, thus played, is a noble sport which increases the dignity of humanity; but at the same time it puts warfare on an unreal footing, gives it an artificial value, and does not correspond to the only justification of war, Pax quaeritur bello:[2] it rather exalts war as the noblest of pastimes, and a thing to be admired and encouraged for its own sake; and this was the principle on which chivalry rested.

The imitation of war as an amusement in peace must be as old as war itself. War dances are common among all savage tribes. Horsemanship in arms was practised as an amusement in peace by Persians, Arabs, Moors and Indians The Greeks had their pyrrhic dance and races in armour, the Romans their Salian dance and Ludus Troiae, from which some derived the word Torneamentum. Vercingetorix, the hero of Caesar’s Gaulish war, was famed as a horseman — a knight-errant, Mommsen calls him — and his picturesque surrender, riding up to the Roman lines in full armour and laying down his arms at the general’s feet, is in the true chivalrous manner. The Goths of the 6th century held games of mimic warfare. The earliest historical instance recorded (by Nithard, a contemporary) is at a meeting at Strassburg between Charles the Bald and Lewis the German, sons of Lewis the Pious, on the occasion of their dividing between them the kingdom of their brother Lothar in 875, at which the vassals of both kings engaged in contests on horseback. Henry the Fowler (876-936) is said to have brought the tourney from France into Germany, or to have invented it in his own country, and from his date till the end of the 15th century we have a complete succession, too complete to be historical, of grand tournaments held by imperial command. Geoffrey of Preuilli, (1056) a Breton lord, is also credited with the invention; ‘torneamenta invenit’: i.e., (we may surmise) drew up the rules of the game

It appears probable that tournaments were first in regular use in France, and Matthew Paris calls them conflictus Gallici. We hear of them in England as early as the reign of Stephen, who is accused of ‘softness’ (mollities) because he could not or would not hinder them. Henry II forbade them, and the knights who wanted to joust had to go overseas. Geoffrey, Count of Brittany, left the English court, and rejoiced in the opportunity of ‘matching himself with good knights’ on the border of Normandy and France. Richard I is said by Matthew Paris to have introduced tournaments into England, in order ‘that the French might not scoff at the English knights as being unskilled and awkward’ (‘tamquam rudibus et minime gnaris’). Richard also got money for the Crusade by granting licences to hold tournaments in certain lawful places, and fined Robert Mortimer ‘ quod torniaverat sine licentia.’ This shows that the fashion had already taken root in England.

The tournament, which may have been invented or regulated in the ninth or tenth century, was in full operation in the twelfth, in every part of Europe, in spite of the opposition of the Church; and was the favoured’ pastime of nobles and gentlemen throughout the Edwardian period,[3] and until beginning of the sixteenth century, when it suffered a the brilliant eclipse in the blaze of knightly and royal display which preceded the age of the Reformation and closed the feudal era. Sovereigns, however, were jealous of anything which might exalt their vassals, and issued many ordinances against unlicensed tournaments, as infringing the royal prerogative, unsettling the counties, and making the castles of great lords a school of private war.[4] The Plantagenet kings, though fond of knightly display, had a clear notion of the serious character of war; and a practical soldier like Henry V looked upon tournaments as an interruption to business, and declined to hold jousts at his wedding with Catherine of France; ‘rather,’ he said, ‘let the king of France and his servants besiege the town of Sens, and there “jouster et tournoyer et montrer sa prouesse et son hardement” ‘ ; he would not mix up war with its counterfeit.

The degradation of tournaments from a knightly contest to a senseless pageant may be seen in its full absurdity in the accounts of tournaments held by Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, René of Anjou the fantastic King of ‘Cyprus and Jerusalem,’ the Duke of Bourbon and others, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The heralds had it all their own way, and the appointments and decorations of the lists resemble those of a circus rather than of a noble contest. The announcement of ‘joustes mortelles et a champs’ issued by John Duke of Bourbon in 1414 may be given here… ‘desirans d’eschiver oisiveté et explecter (exploiter) nostre personne… pensant y acquérir bonne renommée et la grace de la très-belle de qui nous sommes serviteurs’ — the duke proclaims a tournament to be held every Sunday during the space of two years; sixteen lords, knights and squires (whose names are given) will meet all comers in equal number on foot in joustes à outrance, each champion wearing a fetter on his right leg, hung by a chain of gold for the knights, of silver for the squires.

These conceits became more and more extravagant, and came to a height in the reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth. The knights dress up in extravagant disguises and assume ridiculous titles, ‘Cure Loiall,’ ‘Bon Voloire,’ ‘Valiant Desire,’ and so forth. Some hold a pass called ‘la gueule du Dragon,’ which no lady is allowed to cross unless she can find a knight who will break two lances for her. King René built a castle of wood called ‘la Joyeuse Garde ‘ and held feasts there for forty days, with entertainments of pageants in which dwarfs dressed as Turks took part, and tame lions with chains of gold were exhibited. Few were hurt in these later tournaments. Poets recited verses, ladies decked themselves with fine clothes and jewels; the knights seem to have thought more of displaying their arms than of using them, and machines — towers, fountains, scaffoldings, etc. — play a larger part in the show than knightly valour. These absurdities reached if possible, a higher climax of absurdity, in tournaments held before Queen Elizabeth at Greenwich. It is Holofernes on horse-back. To all appearance chivalry was at its most brilliant perfection at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, in 1520. Lances were broken by sovereigns and nobles, banquets were given, all the pomp of heraldry glorified the scene. But the pageant was meant to exalt the three monarchs; the knightly deeds were only an accessory to policy. It was a bravery of processions, pavilions, caparisons, armour, and quaint devices, not a contest of chivalry: and it was the last show of the kind on so grand a scale; for though tournaments continued to be held as pageants till the seventeenth century, more than fifty years after Henry II of France was killed (1551) in tilting with the Count of Montgomeri, they had ceased to bear a real relation to modern war, with matchlocks, cannon, and great numbers of infantry.

In England, as well as on the Continent, the tournament and the exercises which prepared for it were the serious occupation of the gentry, when they were not employed in farming, hunting and hawking; and were as engrossing a pleasure as the turf in later times. How eager the nobles were to engage in this amusement may be judged from the fact that after the signing of Magna Carta, when King John had disappeared from sight, and was known to be collecting an army and preparing to make war upon his subjects, the barons could find no better way of passing the time than in holding a tournament at Staines, the prize of which was a bear, given by a lady to be jousted for.

All the merriment of mediaeval life came together at the fair which accompanied a tournament. Jougleurs,[5] strolling players and musicians were welcome. John de Rampaygne, in the time of John, disguised himself as a jougleur and went to a tournament in France and beat a tabor at the entrance of the lists. These merrymakings brought idle people together, and were the occasion of drunkenness, gambling and other evils, and were probably one of the clerical objections to tournaments.

When the fashion of tournaments was established, the Church set itself in vain to prohibit them. Eugenius III, Innocent III, Innocent IV, published bulls against them. Alexander III, at the Lateran Council of 1179, forbade the holding of ‘detestabiles… illas nundinas vel ferias quas vulgo torneamenta vocant,’ and refused Christian burial to such as fell in them; visions of knightly souls excluded from Paradise confirmed these prohibitions; and as late as the 14th century Clement V renewed the prohibition from Avignon. Yet in 1350 so strong was fashion King John held a tournament at Ville Neuve, near Avignon, at which all the Papal court was present (‘tota curia papali adstante.’) In the same way the Church has always refused to authorise duelling, and fashion has prevailed against the Church: the law of honour takes precedence of the Christian rule.

A tournament was the occasion not only for display of knightly prowess, but also of winning the favour of ladies, and for settling private quarrels.

Tournaments and jousts were carried on, according to strict rule, with armes blanches, i.e., blunted spears and wooden swords. But the license, granted or assumed, of duelling, and the analogy of the wager of battle turned the sham fight into earnest; and once admitted, combats à outrance,[6] in which the lances were sharp and the swords of steel, became a common incident of tournaments. Many instances are recorded of noblemen killed in the lists: Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex, killed (1216) at London in a tournament more Francorum — the phrase shows that they were still looked upon as an innovation on English customs — and Gilbert, Earl of Pembroke (1241) were among the number of Englishmen of note. This was no doubt one of the reasons for the frequent prohibitions which were issued. It is the interest of princes to discourage all forms of private justice, and to prevent irregular meetings in arms. As the fountain of honour and justice, the king claims the decision of quarrels, and cannot allow his lieges to kill each other except in wager of battle or in vindication of personal honour, in presence of his judges or himself.

A clear distinction exists (though it was not always drawn in the days of chivalry) between a generous contest for the love of ladies or for prowess in arms and military distinction, and the wreaking of a personal grudge under the forms of chivalry. The right of personal revenge is assumed in all primitive societies: the point of honour is an addition unknown to the Greeks and Romans, and to be attributed to the individuality of barbarism and the personal savage dignity in Celts and Teutons; and the limitation of it into the hands of justice is a measure of social progress. This limitation was begun by the Church, which prohibited all such contests except those which partook of the nature of an ordeal; it was continued by the civil power, which classified and regulated the wager of battle by the forms and ceremonies of law, leaving the conquered party to be hanged or burnt without Christian burial, and the victor to the ban of the Church; and the courts of chivalry, though they exalted the duty of personal resentment and inflamed the sensitiveness of honour, also raised and maintained at a higher level a sense of responsibility and self-respect in a region of sentiment which was little removed from the primary instincts of savage humanity. Sir Walter Scott is probably right in attributing to the decline and decay of chivalry the license of duelling, and even assassination, which prevailed in the 16th and 17th centuries. The tueur or professional duellist had not yet appeared: but some of the mediæval quarrellers must have approached the character. For instance, an English squire, John Astley, who had killed his man in France, came over to England and there killed another in the presence of Henry VI, who knighted him and gave him a hundred marks.

The modern practice of duelling is derived from the mediæval custom: or rather the fashion of cutting one another’s throats for a hasty word or an ill-considered gesture which prevailed among gentlemen till the middle of this century, and still prevails among French journalists and German officers, was derived from the mediæval superstition, a superstition from which the Greeks and Romans, who fought no duels, were exempt, that a gentleman’s honour demanded the sacrifice of his life at the pleasure of any person of equal rank who chose to insult him. But the mediæval practice, however opposed to reason and religion, imposed checks upon quarrelling. Personal combats in the lists were at any rate carried out in a ceremonious and dignified manner; which can hardly be said of an encounter between two gentlemen stripped to their shirts, fencing or firing with swords or pistols, in some suburban field where the constables are not likely to come.

Personal combats in the Middle Ages were of four kinds; (1) the judicial wager of battle, a solemn appeal to God to defend the right; (2) defence of causes by means of champions such as those mentioned above; (3) contests in the lists ‘for exploration of valour and observation of martial virtue,’ or on questions of personal honour, conducted according to the laws of the tournament, in the presence of the prince, by authority of his High Court of Chivalry; and (4) private quarrels on a question of honour, which, though in agreement with the sentiment and practice of chivalry, were not restrained by the laws of a court of chivalry, and were but a ‘wild justice,’ subject to individual caprice.

The first of these, being part of the ancient custom of ordeal (urthiel, oordeel, ordelium) or appeal to divine justice by fire, water or corsned does not concern us here. We may however remark that the wager of battle was no part of the ancient English law, but was introduced by William the Conqueror as part of the Norman custom. It was imported into English law (1) on appeals of felony, (2) upon issue joined in a writ of right ‘as the last and most solemn decision of real property’ in the presence of the Judges of the Common Pleas, and (3) in courts of chivalry.

The duel upon occasion of the lie given, or supposition of dishonour, was justified by the laws of chivalry; since (as Selden says) truth, honour, freedom and courtesy were incidents to perfect chivalry, and ‘upon the lie given, custom hath arisen to seek revenge of their wrongs upon the body of their accuser… seul à seul without judicial lists.’

So long as it was lawful, or at least customary, for knights to fight in the lists à outrance, it was impossible to ensure that private quarrels would not be settled there. But these combats were not considered the most honourable part of the tournament; and Popes and kings made many attempts to abolish them. Lewis IX, whose superiority in loftiness of character and clearness of vision lifts him far above his contemporaries, attempted to do away with judicial combats, but only succeeded in suis terris.[7] Edward I forbade Sir James de Cromwell to take up a challenge from Sir Nicholas de Seagrave; whereupon the challenger ‘dared him into France.’ Upon a clear quarrel, the laws of chivalry ordained, and the king could not well forbid, that the forms of a judicial combat should be observed, the court being that of chivalry, as in the wager of battle it was (in England) the court of King’s Bench. The court of chivalry, held under the High Constable and the Earl Marshal, with an appeal to the king, had cognisance of all military matters, and included in its purview controversies of coat-armour and precedence, as in the cases of Grey de Ruthven and Hastings (t. r. Hen. III), Scrope and Grosvenor (t. r. Rich. II) and of personal honour impeached. The court of chivalry was concerned with none but noblemen and gentlemen; it had no jurisdiction wherever the common law can give redress; it could not impose or grant pecuniary satisfaction or damages, nor commit to prison. Its sanction therefore was sentimental; but the chivalric sentiment was strong enough to give it authority; and at a time when, as during the Wars of the Roses, military force prevailed over civil authority, the court of the Constable and Marshal was a convenient engine in the hand of an unscrupulous king; as we see from the use made of it by Edward IV and Richard III.

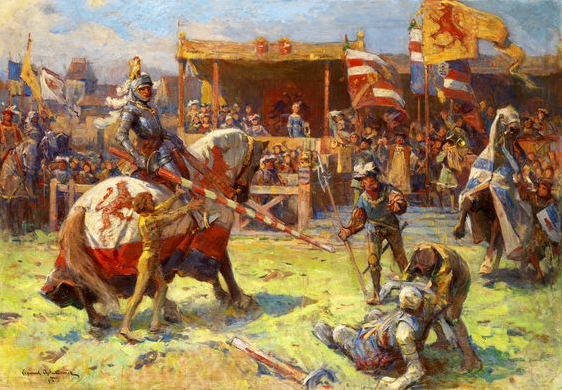

On the evening before the tournament, ‘essays-of-arms’ were held, in which squires and young knights fought with blunt weapons (armes courtoises); and those who acquitted themselves best (les mieux faisans) were allowed to take part in the grand tournoy on the next day, and increased their claims to be admitted to the full honour of knighthood.

The lists, an oval enclosure, were pitched with rows of seats and covered galleries all round. At the middle of the longer side was the gallery or tower of the ladies, and in the middle of this was placed a seat of honour for the Queen of the tournament. The pavilions of the challengers were pitched at either end, each with his shield-of-arms hung at the tent door. Across the centre was a barrier draped with cloth or silk. The ground was kept by squires, who had their own trials-in-arms the day before (les vespres du tournoy); and all the arrangements were ordered by kings-at-arms and heralds, who acted also as judges (diseurs) in case of any breach of rules. The knights were armed by ladies, and received love-tokens from them, to be worn in their honour. The Queen of Beauty and Love gave the ‘gree’ or meed of valour, which might be a chaplet of flowers or leaves, a coronet, a jewel, or arms besides such trophies as the helmet of the conquered knight, his arms and horses, or any badge worn by him. In the romance of Sir Tryamour the maiden Eleyn says:—

Lordyngs, where ys hee

That yysturday wan the gree?

I chese hym to my fere.

Melette, the patroness and prize of the tournament held at Peveril Castle in the Peak, in the reign of Henry II, gave Garin her glove as a token. He went into the lists dressed and armed all in red, and won the prize against all comers. The ladies sometimes chose a Knight or Squire of Honour and gave him a couvrechef de plaisir as a ‘livery’ to wear (livrées de rubans et de galands de soye.) In the story of Perceforest the ladies gave away their veils and other headgear as favours to be worn by the combatants, (guimples et chaperons, manteaux et camises, manches et habits) till at last they all sat with their heads bare (le chef pur) and laughed at each other’s dishevelled condition.

The rules and ceremonies of tournaments were arranged by heralds according to the strictest ritual, and differed little if at all in different countries. The challengers rode forward to the barriers, and touched the shields of the knights with whom they wished to joust. The challenger à outrance struck his opponent’s shield with the sharp end of his spear. Some knights offered themselves to meet ‘all comers’; others reserved themselves to particular opponents, and might, without reflection on their valour, decline to meet any individual adversary.

Besides their armorial bearings, the combatants used many devices in honour of their ladies (sometimes riddles known to their ladies alone) or for disguise. A knight might choose to fight unknown, as Sir Lancelot in the Idylls of the King. In such a case he might wear ‘a red sleeve broidered with pearls,’ or some other favour; or his shield might bear some quaint device, such as the well-known instance of the falcon with the legend:—

I bear a falcon fairest in flight—

Who stoops at me, to death is dight.

or he might appear in arms all of one colour, like the red and green knights in the Morte d’ Arthur, or the Black Knight in Ivanhoe. So we hear of the Knight of the Leopard, the Knight of the Swan, and the like. At a certain tournament a knight appeared with chains attached to his hands and feet, to shew that he was chained to his word of honour (enchaîné à sa parole).[8] Another was led in by a lady, who held the end of his chain. Heraldry comes in here with its multitude of badges, assumed as personal, distinctions for the moment, not like armorial bearings, worn for the honour of the house.

The arms and armour were those used in battle. Besides swords and lances, clubs of crabtree were sometimes used, at least in Germany, and occasionally battle-axes also. The only difference was in the helmet, which was of a conical or cylindrical shape, adorned with plume or crest (cimier), covering the whole head and neck, and resting on the shoulders. The tilting helmet was carried by a squire, when not in use; it may often be seen in monuments, serving as a pillow for the knight’s head.

When the lists were cleared, the jousting began. The squires or pursuivants saw to their master’s arms and horses, and stood in readiness to render help in every way short of joining in the contest, which was only allowed in the mêlée;[9] the knights mounted and set their spears in the ‘rest’ (a half ring attached to the saddle-bow), and waited for the herald to give the signal for charging to the barrier which parted the lists. The object of each was to strike his opponent either on the head, the more effectual but more difficult aim, or on the body. The shock of the heavy-armed man and horse often dismounted both combatants. If both sat firm, the lances were generally shivered; but it often happened that horse and man fell together; and whether the arms were sharp or blunt, ribs or necks might be broken. If the horses did not swerve, and the lances did not break, and either knight aimed true and held his lance firm, mortal wounds were often given. If both knights were unhurt and kept their seats, they wheeled their horses about and charged again with fresh lances, till one or both were unhorsed. Then the victor also dismounted, and the combat was continued on foot with swords. Two men completely cased in mail or plate might slash at each other with swords for a long time without much harm done to either. The combats in the Morte d’ Arthur and other romances last for hours, and the knights rest by consent, to drink and get the cool air, and then set to again, inflicting terrible wounds, which are, in Homeric fashion, minutely described. But they are always ready, after their wounds have been bound up by the ladies, to attend the feast in the evening. In real tournaments, except in the combats à outrance, it is probable that the amount of bloodshed was not great.

The tilting with lances is properly styled the joust, and was held to be of less dignity than the tourney proper, where the knights met each other with swords in the mêlée, a number of champions on each side fighting promiscuously. These encounters, we may believe, were the most dangerous, and therefore the most interesting kind of contest. Single champions might keep cool; but twenty or thirty knights meeting each other on horseback must have fought with the fury of excitement, and armes courtoises were not used in the mêlée. Such combats were often the occasion of much bloodshed. We read of forty-two knights and squires being killed at a tournament. When Edward I was on his way from the Holy Land, (1274), he spent some time in France, and was present at a grand tournament at Châlons. He was assailed by a knight, who tried to drag him from his horse. Edward was the stronger of the two; he lifted his man off the saddle, and rode away with him. His party tried to rescue their fellow, and the fight became so fierce that many were killed on both sides, and the mêlée was called ‘the little battle (parvum bellum) of Châlons.’

The mêlée was a combat for life and death, closed only by the defeat of one party, or by the heralds or the king giving the word to cease. ‘The king hath thrown his warder (truncheon) down’[10] was the signal to stop the battle in the lists at Coventry, when Mowbray and Bolingbroke met to settle their quarrel.

When all was over, the victorious knights either in the lists, or at the banquet afterwards, received their guerdon from the lady of the tournament; usually a garland of flowers, or more substantial prizes, a ‘gerfalcon white as milk,’ ‘three fair steeds great and high, white as snow,’ two greyhounds, and (at least in the romances), the love or the hand of an Emperor’s daughter. A prize of gold pieces was also given,[11] which the victor shared with his comrades or distributed among his squires. The heralds cried ‘Largesse’ and ‘Noël;’ the knights showered small coin among the crowd; there was much shouting and trampling. A feast was then held, at which the ladies as well as their champions were present, enlivened by the music of minstrels, the songs and tricks of jougleurs and other amusements more merry than refined.

Jousts were sometimes held separately from tournaments ‘joustes à tous venans, grandes et plénières.’ These were (according to Ducange) also called Round Tables, where knights engaged in single combat or in equal numbers, and dined together at a round table (the sign of equality in arms) at the charges of the lord who held the Table. Such was the first institution of the Order of the Garter; the Round Tower (‘la Rose’) at Windsor having been built for the purpose.[12]

Other phrases used are behourd, bourde, a wooden castle to be assaulted and defended; barrière, where two troops of combatants fought with axe, sword and mace, to force a bar placed across the lists; and pas’ darmes, where a pass (clusa, clausura) was to be held against all comers. At the jousts in which Henry II of France was killed (1559), there was a pas’ darmes; and the royal proclamation ran, ‘le pas est ouvert par Sa Majesté très-chrestienne… pour estre tenu contre tous venans douëment qualifiez.’ The details of every part were drawn out in enormous prolixity and triviality by heralds, whose ‘silly business’ was as unduly glorified then as it has been unduly disparaged since.

The tournament in Ivanhoe is a good description of what ordinarily took place. Scott was not an acute archaeologist, and he has no authority for making a Templar engage in a tournament, a thing forbidden by the rules of the Order; and the details generally are drawn rather from Froissart and Malory than from any accounts of the time of Richard I; but with these exceptions the account is as truthful as it is brilliant.

Tournaments continued in France till Henry II was mortally wounded (1559) by Montgomery; the next year also, the Duke of Montpensier, a prince of the blood, was killed at a tournament. In England and other countries they went on still, increasing in costliness and unreality. Henry VIII always won the prize. The knights vied with each other, not so much in knightly skill as in splendid disguises, and the invention of extravagant costumes and devices. ‘Bevis was believed’ by those who saw these brilliant masquerades. But there was no seriousness in it all. The combats were not dangerous, the knights and ladies were playing a fantastic game. Nothing more extravagant was ever devised than the tournament celebrated by Henry VIII after the birth of his son Prince Arthur, whose name bears witness to the attempt to revive obsolete fashions.

(Continue to Part 6)

_______________________________________

[1] Lord of the Isles, Canto v.

[2] Peace is obtained through war. [ed.]

[3] John of Brabant, who travelled in England 1292-3, was present at tournaments held in seven places in the course of three or four months; and in the time of Edward III, we hear of seven tournaments of great magnificence being held in one year in England.

[4] These prohibitions of tournaments constantly occur in English history, and are to some extent an indication of the condition of the country. Edward II (see Rymer’s Fœdera) issued a great number of letters forbidding all persons torneare, burdeire, justas facere, aventuras quaerere, seu alias ad arma ire… sine licentia nostra speciali. The reason given is for fear of breach of the peace and terrifying quiet people. No tournament, e.g. is to be held within six miles of Cambridge, to protect ‘tranquillitatem ibidem studentium.’ Such meetings were an excuse for disaffected persons to meet and consult to the King’s damage, and might be, and no doubt were, misused for purposes of family feuds and private warfare. So, too, in France, Philip IV (1312) forbade all ‘astiludere vel justare, sub poena amissionis armorum.’

[5] Jougleur = ioculatar — not jongleur, as it is commonly written.

[6] Outrance (utterance) is extremity or completion of the contest by the death, flight, or confession of one of the parties. The opposite to à outrance was à plaisance.

[7] In his own lands. [ed.]

[8] The Green Knight, who did wonderful feats of arms at Ascalon and Acre in the third Crusade, wore chains upon his helmet. Green was the especial colour of knights errant.

[9] From the squire’s help to his master is derived the custom of ‘second’ in a duel, and their separate encounters with the opposite seconds.

[10] Shakespeare, King Richard II, Act i.

[11] So large a sum as 100,000 pieces of gold is mentioned. But this was a king’s ransom, and worth a million and a half in modern money.

[12] The table ran along the walls of the tower, the guests sitting on one side of it, facing inwards. In the centre were the carvers, sewers, minstrels, etc.