Editor’s note: The following is extracted from A History of Jazz in America, by Barry Ulanov (published 1952).

On February 2, 1932, Duke Ellington brought his Famous Orchestra, as the record labels have it, into a New York studio to record three sides. One of them became a jazz classic, “Lazy Rhapsody.” One of them, “Moon over Dixie,” had almost no interest for Ellington fans, then or now. One of them, “It Don’t Mean a Thing if It Ain’t Got that Swing,” named the whole era that was to follow in three years. Ivy Anderson sang it with all the strength and joy which her first work on records had to have; in her swinging singing and the band’s similar playing the title was handsomely demonstrated. In December 1935 a bright little novelty record, with almost no discernible meaning except the implicit joy in its title and the execution of the meaning thereof, inaugurated modern jazz in general and the first few years of it in particular. The record was Eddie Farley’s and Mike Riley’s “The Music Goes ‘Round and ‘Round”; the era which was beginning was called Swing.

Maybe it was the swing away from the worst years of the depression that made the Christmas of 1935 the logical time to start the new era. Maybe the American people, or that group interested in the dance anyway, had had enough of Guy Lombardo and Hal Kemp and all the more pallid versions of jazz. Maybe this was simply proof that jazz would never die as long as fresh talent was available. Whatever the reason, it was the freshness of the music that Benny Goodman and his musicians played that made swing as inevitable as the success of “The Music Goes ‘Round and ‘Round” was incalculable. Benny was the logical man to take charge of the new music. Of all the talented musicians who came out of Chicago, he was clearly the most polished, the most assured, the most persuasive stylist. Of all the instruments with which one could logically front a jazz band, his was the last to reach public favor. Of all the clarinetists to achieve esteem, if only among jazz musicians, he was clearly the most generally able and specifically facile.

Before Benny, Sidney Bechet and Johnny Dodds and Jimmy Noone had established certain clarinet procedures, but none of them, in spite of their individual and collective ingenuities and skills, had the kind of sound that made Benny’s success so certain. Popular success in the band business has, like popular success in so many other kinds of popular culture in America, always depended upon some novelty interest. Benny’s graceful, skillful maneuvering of clarinet keys certainly had such interest to dancers and listeners alike in 1935. It didn’t matter what he played “The Dixieland Band” or “Hooray for Love,” “King Porter Stomp” or “Yankee Doodle Never Went to Town” — it was that infectious compound of lovely sound and moving beat that made Benny his large audiences. Sound and beat were both fashioned over many years of playing experience, most notably on the records with Ben Pollack from 1926 to 1931, and then with various bands such as Red Nichols and the Whoopie Makers, Irving Mills’ Hotsy Totsy Gang, Jack Pettis, and various combinations under Benny’s own name. When Benny became a success as a band leader he could look back to a career that was traditional for jazz and had ranged over most of the possible styles of the middle and late twenties and early thirties. His playing experience moved all the way from short-pants imitations of Ted Lewis to every possible kind of dance, radio studio, night club, ballroom, and one-nighter job. None of the problems he had to face were new to him.

Benny Goodman’s first impact upon the country at large was the third hour, which Benny had all to himself, of the three-hour National Biscuit program which was sent over the National Broadcasting Company network every Saturday night. Working with most of New York’s first-rate white jazzmen, with many of whom he had shared stands before, Benny put together a startlingly good band for radio. He had made records with the Teagardens, trumpeter Manny Klein, Joe Sullivan, Artie Bernstein, and Gene Krupa; his standards were high. In his broadcasting orchestra he had the trombonist Jack Lacey, the lead alto saxophonist Hymie Schertzer, Claude Thornhill on piano, and George Van Eps on guitar. After a dismal showing at Billy Rose’s Music Hall, a theater-restaurant which was distinctly not the right setting for his kind of music, he put together a band with which to go out on the road, and improved on his radio personnel. Gene Krupa became his drummer, Jess Stacy his pianist, Ralph Muzillo and Nate Kazebier his trumpeters. Though his saxophones and trombones were something less than the combinations of the best musicians that his previous recordings had suggested he might have, as sections they were well disciplined and swinging, on the whole the abiding virtues of the Goodman band that played the music called swing.

“Swing,” as some of us knew then and all of us know now, was just another name for jazz; it was a singularly good descriptive term for the beat that lies at the center of jazz. It certainly described the quality Benny’s band had. With Fletcher Henderson as his chief arranger, Benny’s music had a quality that only the very great big bands had had before, and it reached more people than jazz had ever dreamed of for an audience. Fletcher’s writing was such, so tight, so adroitly scored in its simplicity, that each of the sections sounded like a solo musician; the collective effect was of a jam session. With such an effect, it was possible to record essentially dreary material like “Goody Goody” and “You Can’t Pull the Wool over My Eyes” and give it something more than a veneer of jazz quality. A big-band style was set that was never lost again, as the distinguished qualities of New Orleans and Chicago jazz had been, at least to the public at large, after their peak periods. After the emergence of the Goodman band, all but the most sickly commercial bands tightened their ensembles, offered moments of swinging section performance and even a solo or two that were jazz-infected. Kay Kyser, in his last years as a working bandleader, hired Noni Bernardi to lead his saxes, and Noni, who had played alto with Tommy Dorsey, Bob Crosby, Charlie Barnet, and Benny for a while, converted not only his reeds but the band itself from a series of ticks and glisses into a dance orchestra of some distinction, with jazz inflections that had some of us looking forward to each new record. When Harry James became a successful trumpeter-leader as a result of a crinoline and molasses version of “You Made Me Love You,” the essential swing style was preserved and some first-rate jazz sandwiched in between nagging laments and rhapsodies and pseudo-concertos for trumpet and orchestra. Charlie Spivak paid occasional respects to his jazz background, and there was some fair jazz in the music of the Dorsey Brothers after they split up and led their separate bands; in the band of the ex-society leader, Al Donahue; in radio studio groups; even in more than a few territory bands, those minor-league outfits that build a name and a public only within an easily negotiable geographical area.

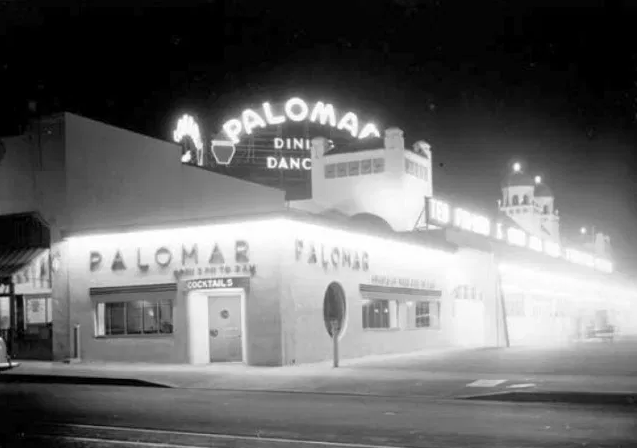

Benny’s success was far more than a personal one; his influence was lasting; his way was others’ too. When Benny turned a poor road trip into a jubilant roar of approval at the Hollywood Palomar Ballroom, the cheers were not only for his band but also for the school of jazz it represented. Other bands playing music even vaguely related to Benny’s were almost equally well received for a while, and it became expedient to identify one’s jazz as “swing.” Fortunately some of the bands that benefited from Benny’s success were deserving, and a few of them developed and expanded the way of playing jazz called “swing.”

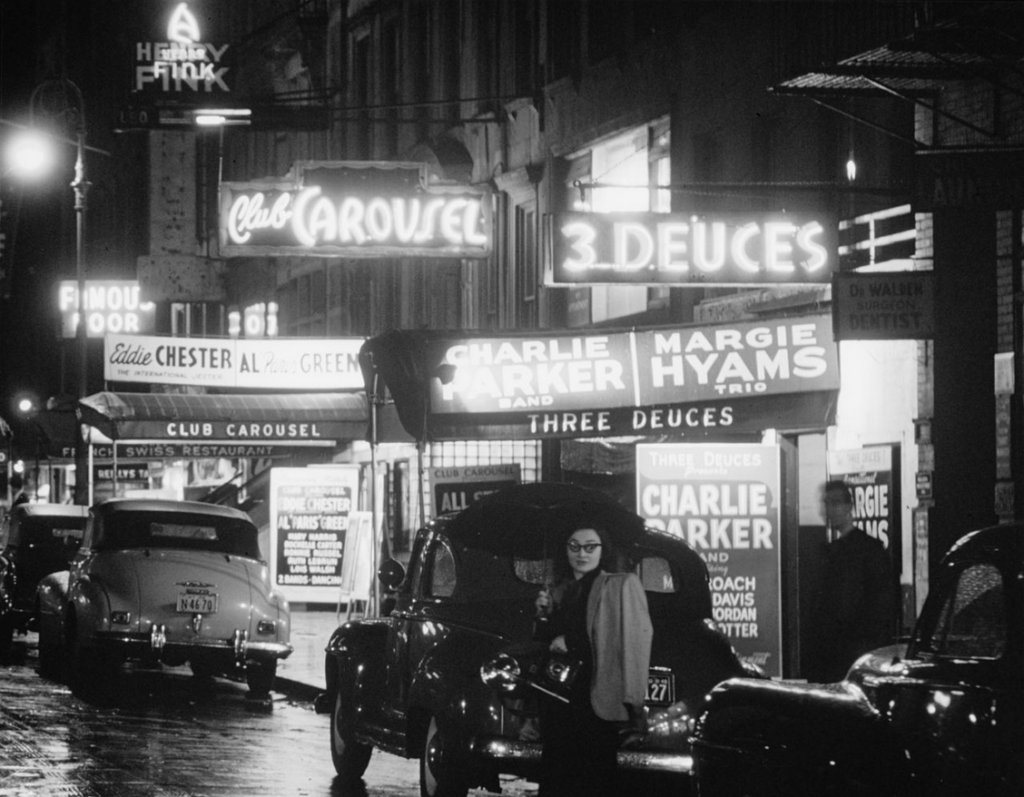

Bob Crosby, Bing’s singing younger brother, took over the distinguished remnants of the Ben Pollack band in 1934, and it, more than any other band, large or small, brought New Orleans jazz back to life. Bob had as his band’s centerpiece one of the best musicians ever turned out by that city, Eddie Miller, and, to match Eddie’s tenor, Matty Matlock’s clarinet; Yank Lawson’s trumpet; Nappy Lamare’s personality, vocals, and guitar; Bob Haggart’s bass; and Ray Bauduc’s drums. After the demise of the band the Dorseys led together in 1935, Tommy turned soft-spoken ballads into a big business and Jimmy tried several things, finding their chief musical success with a semi-Dixie style built around Ray McKinley’s drums, and box office appeal with alternately up-tempo and medium or slow vocal choruses by Helen O’Connell and Bob Eberle. Charlie Barnet, who had had a New York playing and recording career like Benny’s, if shorter, moved a step beyond the others in his band’s performances of Duke Ellington manuscript; and Woody Herman, identified like Charlie with the squat little Fifty-second Street bandbox, the Famous Door, played the blues and pops and sang standards handsomely.

Fifty-second Street came to enthusiastic life shortly before Benny bowled over the Coast and then took over Chicago. The lifeblood in his trio and quartet, Teddy Wilson, had been an interlude pianist at the old Famous Door, across the street from Barnet’s and Herman’s later headquarters. The kind of performance Benny’s small units made popular after Teddy drove out to Chicago to play a concert with the Goodman musicians in March 1936 was a Fifty-second-Street session: any number of instruments short of a big band could be combined as long as the beat was steady and the time allotted solos expansive. There were all kinds of groups along Fifty-second Street’s two playing blocks in the thirties and early forties: Red McKenzie and Eddie Condon, together and apart, at first with Bunny Berigan, then with the cast that became Nick’s permanent two-beat repertory company, Pee Wee Russell, Max Kaminsky, Wild Bill Davison, George Brunies, and George Wettling; Fats Waller, before Benny hit and carried him along with the others who played that kind of music; John Kirby, an Onyx fixture with Charlie Shavers, Buster Bailey, Billy Kyle, and O’Neil Spencer, the Spirits of Rhythm, and Frankie Newton’s band; singers like Billie Holiday and pianists like Art Tatum, who eventually became the Street’s major luminaries. Perhaps the most significant of all the bands was the one that, even more than the Goodman band, typified, expanded, and carried swing forward — Count Basie’s.

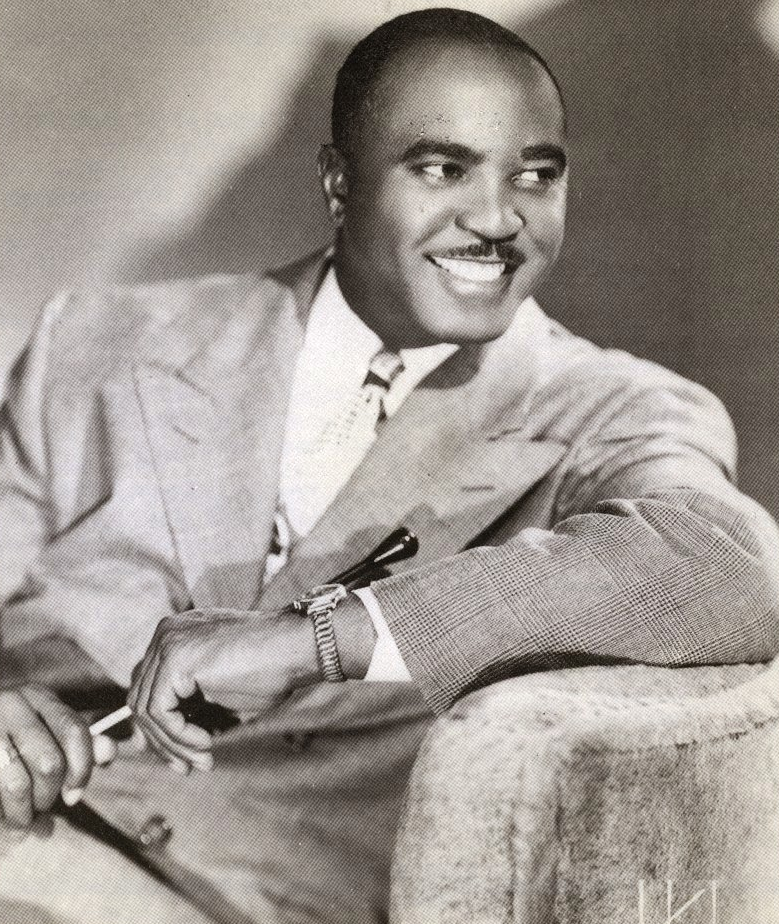

The Red Bank, New Jersey, pianist William Basie, who had started as a drummer, had become a Kansas City jazzman, working with Bennie Moten, then with his own twelve-piece band at the Reno Club. Benny Goodman and John Hammond heard the band out of a short-wave station, W9XBY, recognized extraordinary skills in the jumping rhythm section and the fresh patterns of Lester Young’s tenor solos. With Benny’s help, John, the most articulate and influential of the jazz critics of the thirties, did something about it. Basie moved to the Grand Terrace in Chicago, made records for Decca, and came on to New York’s Roseland Ballroom in 1936. He picked up fans and followers as he went from club to record date to ballroom; the best of the swing styles was clearly his; the bridge to later jazz was built.

The illustrious solo moments of the Basie band were those of Lester Young on tenor and Harry Edison on trumpet, but they weren’t fully appreciated until some years after the band had passed its peak. The real star was what Paul Whiteman called Count’s “All-American Rhythm Section” in a 1942 article in Collier’s, selecting the best musicians in jazz. Freddy Greene was a guitar rock; Joe Jones’ drum tempos and Walter Page’s bass intonation were neither as steady nor as consistent; and Basie himself provided only piano decoration, albeit charming. It was a unit, however, one which took fire from Joe’s cymbals and warmth from Walter’s strings, got good guitar time, and was capable of sustaining a string of choruses all by itself, with the titled head of the band and the section tinkling on the off-beats. “I don’t know what it is,” one of the Basie veterans once said. “Count don’t play nothing, but it sure sounds good!”

There were others in the band who sounded good, too: Benny Morton, whose trombone was languorous always and often lovely; Dickie Wells, who made funny noises into fetching phrases on the same instrument; Vic Dickenson, who carried the sliding humor further. The famous Basie trumpeter when the band was most famed, from 1936 through 1942, was Buck Clayton, whose identifying grace was delicacy. When joined with a subdued Lester and Dickie and the rhythm section for a Cafe Society Uptown engagement, Buck’s muted trumpet set the style for the small band within the large and pointed to Basie’s major achievement: the ability to keep the roar implicit and the beat suggestive. At other times, it was all ebullience, a genial fire stoked by rotund Jimmy Rushing’s robust blues shouting, the brass section’s stentor and the saxes’ strength. Men like the late Al Killian, of the leathery lungs, passed through the trumpet section. Tab Smith, an insinuating alto saxist of the Hodges school, replaced Earl Warren, the band’s original ballad singer and lush reed voice, for a while. Several tenors tried at various times to duplicate the furry sound of Hershal Evans, who died early in the band’s big-time career — most notably and durably Buddy Tate. Jack Washington was a baritone player of some distinction and power, the key quality of an organization that for a while blasted every other band out of the way.

Jimmie Lunceford’s showy musicians moved into prominence earlier than the Basie musicians — and moved out earlier. With the death of Lunceford in Oregon on July 12, 1947, the last edition of a once-great organization, already fading badly, was washed out completely. But the style remains, firmly embedded within the grooves of a select number of phonograph records.

Jimmie, a Fisk University graduate, recruited the nucleus of his first band at a Memphis high school, where he was an athletic instructor. He picked up Sy Oliver in the early thirties and his style was set, never to vary importantly until his and his band’s demise. That style, sooner or later, influenced almost every important band in jazz. It was the most effective utilization of two-beat accents discovered by any jazzman; it made a kind of impressive last gasp for dying Dixieland, with its heavy anticipations, its almost violently strong and whisperingly weak beats, its insistent, unrelenting syncopation.

There were about eight years of prime Lunceford, beginning with the Cotton Club engagement the band played in 1934, ending with the exodus from the band of Willie Smith in 1942. At first the band played flashy, stiff instrumental in the Casa Loma manner, such Will Hudson specials as “White Heat” and “Jazznocracy.” These and other Hudson pieces were used in turn by Glen Gray’s Casa Loma Orchestra, a group of Canadian musicians who excited some enthusiasm in the year just before Benny Goodman took over, more because of their shrewd balance of ballads and mechanical jazz than because of any real musical quality. When Sy Oliver became Jimmie’s chief arranger in 1935, the parade of two-beat specials most irresistibly associated with LunceforcTs name began: “My Blue Heaven/’ “For Dancers Only,” “Margie,” “Four or Five Times,” “Swanee River,” “Organ Grinder Swing,” “Cheatin’ on Me,” ” Taint What You Do,” “Baby, Won’t You Please Come Home,” etc. Bill Moore, Jr., showed up to replace Sy when the latter left to join Tommy Dorsey; Bill left a vital impression on the band’s books with his “Belgium Stomp,” “Chopin Prelude,” “Monotony in Four Flats,” and “I Got It” (the last backed on records by Mary Lou Williams’ sensitive “What’s Your Story, Morning Glory”).

Coupled with the instrumental style of the band, which, much as it emphasized its hacking two-beat, depended upon section precision, was a singing manner. Jimmie’s boys whispered, wheedled, cozened, rather than sang. Out of the first husky efforts of the Lunceford Trio (Sy, Willie, guitarist Al Norris) grew the individual vocalists, Oliver and Smith, Joe Thomas, later Trummy Young. Their rhythmic attack at a low volume held a brilliance of innuendo which never failed to grab an audience’s attention (for example, Trummy’s “Margie,” Sy’s “Four or Five Times,” Willie’s “I Got It,” Joe’s “Baby, Won’t You Please Come Home” and “Dinah”) as Jimmy Crawford’s brilliant drumming grasped its pulse.

The band’s soloists were always secondary to the arrangements in Lunceford’s heyday, but some genuinely distinctive individual sounds did emerge from the group. Trummy Young played a wistful trombone. Willie Smith’s agile, enthusiastic alto remains the most in favor, but there are tenormen who swear by Joe Thomas’s soft tone, and those of us who followed the band eagerly in the mid-thirties remember with pleasure the solo trumpeting of Eddie Tompkins, who was killed in war maneuvers in 1941. Eddie can be remembered for other things, too: when the trumpet section consisted of his horn, Sy’s, and first Tommy Stevenson’s, then Paul Webster’s, it was a high-flying unit, not only in the screeches it sometimes played in tune, but in its instrumental gymnastics, in its wild flinging of its three trumpets into the air in perfect unison.

At its zenith, Lunceford’s was the show band, whether in its military formations on the stage or ballroom stand, in its multiple doubling of instrumentalists as singers, or its comparatively precise performances. Even after it passed from the serious consideration of musicians and critics as a contemporary jazz outfit, its old records retained interest, its old appearances stirred a nostalgic tear. Jimmie never did much more than wave a willowy baton, smile tentatively, and announce the names of his soloists and singers, but he held title to one of the genuinely distinctive swing bands.

Some of the powerhouse quality of the Lunceford band was picked up by its most slavish imitator, Erskine Hawkins and the Bama State Collegians. The self-styled Gabriel of the trumpet never did as much with the youngsters he brought from Alabama State University to New York as he might have. But he was luckier than most of the men who brought flashy outfits into New York for one or two or a dozen appearances in the late thirties and early forties, to leave an impression of crude strength and undeveloped talent and no more; he at least made enough of a reputation to be confused with Coleman Hawkins by some of the unknowing; he had a hit record grow out of one of his band’s original works, “Tuxedo Junction.” The Jeter-Pilar band came in from St. Louis several times and always charmed its listeners, but never had the soloists or the scores to make the charm linger. The Sunshine Serenaders came in from Florida and made a lot of attractive noise, but never with an identity all its own. The Harlan Leonard band blew in from Kansas City, and its breezy airs and brassy competence, coupled with the booming impression of the Jay McShann band and Count Basie, gave the impression for a while that there was such a thing as a Kansas City “style.” But when these were compared with the Andy Kirk band, so very different really, so much more timid, so much more a matter of Mary Lou Williams’ writing and playing talents, the style disappeared along with the comparison.

There was more of the Kansas City style — if Leonard and McShann and Basic were representative of it — in bands that had rarely if ever seen the Missouri metropolis. The massive Mills Blue Rhythm Band, bumping along behind the solos of Red Allen on trumpet and J. C. Higginbotham on trombone, was an example of this sort of jazz. Willie Bryant’s swinging group of 1935 and 1936, with first Teddy Wilson, then Ram Ramirez on piano, with Puddin’ Head Battle on trumpet, had much of the same spirit, some of it because of its leader’s sprightly announcing and singing wit. The minor outfits — Billy Hicks and his Sizzling Six, Al Cooper’s Savoy Sultans, Buddy Johnson’s band — all had it in varying measure. Cab Calloway bought it when he began to fill out his sections with men like Milton Hinton on bass, Chu Berry on tenor, and Cozy Cole on drums in 1936 and 1937 and then Jonah Jones on trumpet a few years later. When Cab began to buy manuscript from men of the quality of Don Redman, he had a band to compete with Basie and Lunceford and even Ellington. If his box office could have matched his budget, if his personal public and the new band’s following could have been coupled, his contribution to jazz history might have equaled his flamboyance and his fervor as a singer.

The white bands got the first swing customers; the Negro outfits followed close behind. About the same time that Basie was emerging as a national figure, so were the bands at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem — Teddy Hill’s and Chick Webb’s; so was Jimmie Lunceford, with his precision scoring and precision musicians; so was the band that Jimmie followed at the old Cotton Club, Duke Ellington’s. Duke was almost as much in demand for rhythm and hot-club concerts as Benny; his experiments, such as the four-part “Reminiscing in Tempo,” were the subject of violent controversy among musicians and aficionados; his tone colors were adopted by all kinds of bands and musicians. Along with the Negro bands themselves, individual Negro musicians and singers were beginning to be accepted, even with white bands. Benny Goodman added Lionel Hampton to his trio and made it a quartet. Later, in the first of several reorganizations of personnel after short-lived retirement, Benny took on Cootie Williams and Sidney Catlett, and Charlie Christian was his featured guitarist and perhaps the very best musician he ever had.

Artie Shaw showed himself something more than an imitator of Benny when he signed Billie Holiday as his singer, and, though this was not an altogether successful arrangement, the hiring of Lips Page for Artie’s comeback band in 1941 and Roy Eldridge in another return edition in 1944 proved entirely satisfactory on all counts. These were instances in which Artie’s threats to revolutionize jazz and the business attendant upon the music leaped beyond words into inspired deeds. It was not always that way, partly because Artie’s attempts at the sublime were undisciplined, partly because the sublime was not always accessible, even to the impeccably disciplined of jazz.

The first attempt, after an early success as a radio studio and jobbing clarinetist in New York, was with a combination of solo jazz instruments, rhythm section, and string quartet. In various combinations in 1936, it failed commercially, and musically too, because of a certain protective pallor that approached indifference. The new few editions of the stringless Shavians led to a simple swinging skill by 1938, best illustrated for the public by the fabulously successful recording of “Begin the Beguine,” best demonstrated for musicians by the authority of soloists like Georgie Auld on tenor, Les Robinson on alto, Chuck Peterson and Bernie Privin on trumpet, and Artie himself on clarinet, with a formidable assist the next year by young Buddy Rich on drums. Then in the fall of 1939 Artie ran away from a choice engagement at the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York, ran to Mexico because, he said, he was sick of the spectacle and the corruption of the jazz business. In a few months he was back with a lot of strings and at least one shrewdly chosen Mexican song, “Frenesi,” which made his lush fiddle sound popular on records. With the strings, Artie made a variety of attractive dance records through 1942. With Billy Butterfield at first, then with Roy Eldridge; with Johnny Guarnieri on harpsichord at first, then with Dodo Marmarosa on piano, Artie recorded some small band jazz, riffy but fresh. The first group of small band sides made in 1940, the second made in 1945, joined to the 1938-1939 big-band jazz, represent Artie Shaw’s swing contribution. Like his own playing, these alternately move and plod, occasionally catch fire and hold the torch brilliantly.

The accomplishment of the swing era, 1935-1940, is difficult to evaluate. Its achievement was of the magnitude of that in the New Orleans period. It found an audience for every variation on what was essentially the New Orleans-Chicago theme with an added Kansas City seasoning, and although some of the less talented and more backward recipients of the success Benny Goodman brought them made ungrateful critical noises, they were restored to jazz life in the process. Nobody, least of all Benny himself, thought that a conclusion had been wrought and an end to the development of jazz accomplished. Some, as a matter of fact, musicians and audiences both, suddenly became aware of music outside jazz and became humble about the hot music, the improvisation, the beat. But, whatever the limitations, the cliches, and the hollow repetitions, a new vitality had been discovered, continuity with Chicago had been established. Such was the conviction of vitality that, in 1950, when jazzmen were casting around again for a renewal of their forces and an enlargement of their audiences, they looked back with excited interest at the swing era — whatever the term “swing” itself meant, whatever the countless kinds of music that had masqueraded under its name.

Confusion surrounded the use of the two terms “swing” and “jazz” as soon as swing became popularly accepted. There was one school of thought, of which critic Robert Goffin was the most rabid exponent, that believed “swing” denoted the commercialization and prostitution of real jazz, that it had partly supplanted jazz, and that it consisted only of written arrangements played by big bands, whereas jazz consisted only of improvised music played by small bands. Another school of thought held that good jazz, whether played by one man or twenty, must have the fundamental quality of swing, a swinging beat, and could therefore legitimately be called swing, and that despite the different constructions put on the two terms by some critics, both words stood for the same musical idiom, the same rhythmic and harmonic characteristics, the same use of syncopation. Confusion regarding the meaning of the word “jazz” developed even among musicians themselves. A leader of a big band, telling you about his three trumpet players, for instance, would say, “This one plays the jazz,” meaning that the man in question handled the improvised solos. Yet many musicians began to use the adjective “jazzy” to mean “corny,” and some of them began to narrow down the meaning of the noun “jazz” to denote corn.

Before the word “swing” became popular there was none of this confusion. Fletcher Henderson and others played arrangements with big bands more than twenty years before the official arrival of swing as a jazz style, and nobody thought of calling his music anything but jazz. Yet during the swing era the same kind of music played by big bands was considered by the Goffin school to be something apart from and interfering with jazz — just as, still later, the same type of critic deplored bebop and cool jazz and disparaged these developments in the evolution of jazz as departures from and betrayals of the pure tradition.

The truth is that there is absolutely no dividing line between swing and jazz. Roy Eldridge hit the crux of the matter at the height of the controversy. “Difference between jazz and swing? Hell, no, man,” he said. “It’s just another name. The music advanced, and the name advanced right along with it. Jazz is just something they called it a long time ago. I’ve got a six-piece band, and what we play is swing music. It’s ridiculous to talk about big bands and small bands as if they played two different kinds of music. I play a chorus in exactly the same style with my small band backing me as I did when I was with Gene Krupa’s sixteen pieces.”

Fletcher Henderson agreed with Roy, though he made a slight distinction: “There is a certain difference in the technical significance; swing means premeditation and jazz means spontaneity, but they still use the same musical material and are fundamentally the same idiom. To say that a swing arrangement is mechanical whereas a jazz solo is inspired is absurd. A swing arrangement can sound mechanical if it’s wrongly interpreted by musicians who don’t have the right feeling, but it’s written straight from the heart and has the same feeling in the writing as a soloist has in a hot chorus. That’s the way, for instance, my arrangement of ‘Sometimes I’m Happy’ for Benny was written — I just sat down not knowing what I was going to write, and wrote spontaneously what I was inspired to write. Maybe some arrangements sound mechanical because the writers studied too much and wrote out of a book, as it were too much knowledge can hamper your style. But on the whole, swing relies on the same emotional and musical attitude as jazz, “or improvised music, with the added advantage that it has more finesse.”

Many devotees of earlier jazz, whose nostalgic yearnings for the old idols of a dying generation involve an indiscriminate contempt for anything modern, claimed that swing musicians paid too much attention to technique and too little to style, that the fundamental simplicity of jazz was lost in the evolution of swing. Theirs was an unrealistic argument. It is true that much of Louis Armstrong’s greatness lay in the pure simplicity of his style and that he often showed a profound feeling for jazz without departing far from the melody; it is also true that such swing stars as Roy Eldridge, whom most of the fans of the old jazz despised, made vast technical strides and played far more notes per second in their solos. But it is true too that there were times when Louis’s playing was complicated, and there were New Orleans clarinetists whose music was just as involved and technical as some of the jazz played by later musicians. More important, really good jazz musicians of any period or style have never used their technique as an end in itself; they use it as a means to achieve more variety, more harmonic and rhythmic subtlety in their improvisations. If somebody like Jelly Roll Morton had been blessed with a technique even remotely comparable with Earl Hines’ or Art Tatum’s, he would undoubtedly have been a far finer pianist, and it wouldn’t have changed him from a jazzman into a swingman, because basically there is no difference between the two.

Most people who like jazz of any style, school, or period admire Duke Ellington, whatever their reservations. Do they consider his music swing or jazz or both or neither? If the devotees of early jazz were to follow their theories through consistently and logically they would have to say that an Ellington number was swing while the arranged passages were being played, but as soon as a man stood up to take a sixteen-bar solo, it became jazz. If, as so often happened with the Ellington band, a solo that was originally improvised was so well liked that it was repeated in performance after performance until it became a regular part of the arrangement, then would it still be jazz? The question becomes even sillier when you realize that music such as Charlie Barnet’s, Hal Mclntyre’s, and Dave Matthews’, and that of other prominent swing musicians, written in exactly the same idiom as Ellington’s, sometimes using identical arrangements and sometimes entirely different arrangements in the same style, was passed off or ignored by these jazz lovers as “commercial swing” of no musical interest.

Since the word “swing” was accepted by the masses and couldn’t be suppressed, it might have seemed logical to let the term “jazz” fade out of the picture entirely and to call everything swing from 1935 on, whether it was Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong, Eddie Condon, or Duke Ellington. But that word “jazz” has a habit of clinging. It has figured in the title of almost every book written on this type of music, from Panassie’s Le Jazz Hot on; an important exception, curiously enough, was Louis Armstrong’s book, Swing That Music. Louis, although he has always been one of the chief idols of the nostalgic jazz lovers, liked the new word and used it frequently in preference to “jazz.” Of the distinction between the two terms, he said, “To tell you the truth, I really don’t care to get into such discussions as these. To me, as far as I could see it all my life, jazz and swing were the same thing. In the good old days of Buddy Bolden, in his days way back in nineteen hundred, it was called ragtime music. Later on in the years it was called jazz music, hot music, gutbucket, and now they’ve poured a little gravy over it and called it swing music. No matter how you slice it, it’s still the same music. If anybody wants to know, a solo can be swung on any tune and you can call it jazz or swing.”

Benny Carter, always a thinking musician, expressed essentially the same sentiments in different words, in an ordered argument: “I don’t think you can set down any hard and fast definition of either ‘jazz’ or ‘swing.’ Both words have been defined by usage, and a lot of people use them in different ways. For instance, a lot of musicians use the word ‘jazz’ to denote something that’s old-timey and corny. As I understand it, though, ‘jazz’ means what comes out of a man’s horn, and ‘swing’ is the feeling that you put into the performance. Well, the jazz that comes out of the horn happens in so-called swing performances too. So even if ‘jazz’ and ‘swing,’ as words, do mean two separate things, as musical elements they’re very often combined in one performance, and to talk about swing having replaced jazz, or followed it, is just nonsense.”

Red Norvo wanted to junk the old word. “The word ‘swing’ doesn’t signify big bands playing arrangements — that’s the most obvious thing in the world. My records with the Swing Sextet and Octet had no arrangements, but they were swing, just the same as other records I made which did have arrangements. ‘Swing,’ to me, stands for something fresh and young, something that represents progress. Jump is another good name for it, too. I certainly hope it isn’t jazz we’re playing, because jazz to me means something obnoxious, like that Dixieland school of thought.”

Lionel Hampton was differently concerned about the names people called his music. In his years with Benny Goodman (1936-1940) he was content with “swing,” particularly when used as a verb to describe his own performances with the Goodman Quartet and those of the various groups of musicians who recorded under his leadership in the distinguished jazz series he made for Victor. Both Lionel as an individual and his pickup bands swung. So did his first big band, organized in late 1940 — partly because of his own spectacular drive; partly because of his guitarist, Irving Ashby, a much more sparkling musician then than later with the King Cole Trio; partly because of Lionel’s other soloists, especially the violinist Ray Perry. Later editions of Lionel’s band intensified this concern of his with the beat. The band that played a concert at Symphony Hall in Boston in the winter of 1944 and at Carnegie Hall in New York in the spring of 1945 was an overwhelming organization which swamped the thirty-odd strings Lionel gathered for the concerts and almost accepted discipline. But in spite of a few subdued solos from the gifted but generally noisy tenor saxophonist Arnett Cobb and a dynamically versatile brass section, all the music ultimately gave way to wild exhibitions by the many drummers who passed through the band and by Lionel himself. It was engaging for a while, but after a few years of the frenzy of “Flying Home,” “Hamp’s Boogie Woogie,” and “Hey-Ba-Ba-Re-Bop” one could listen only for the occasional moments of Milt Buckner’s chunky piano chords or a random sax or brass solo of distinction. Lionel called his music “boogie woogie,” “rebop,” “bebop,” or “swing,” as the fashion suggested, but at its best it was only the latter, and at its worst it was a travesty of the other styles, if any representation of them at all. Finally, those who were interested in music came only to hear Lionel play vibes and were best satisfied with his slow, insinuating ballads, especially his big-band “Million-Dollar Smile” and the lovely set of solos with organ and rhythm accompaniment, released by Decca in 1951.

The music that will longest be associated with Hamp is not his own band’s, in spite of its charged moments, but rather the combinations of other men’s musicians he led in the Victor studios in Hollywood, Chicago, and New York from 1937 to 1940. His first date featured Ziggy Elman, and so did his last significant session but one before recording with his own men. Ziggy was typical: he was a lusty trumpeter with a personality perfectly attuned to the manners and might of swing. Cootie Williams was another of the same stripe. So were Red Allen and J. C. Higginbotham, Benny Carter, Chu Berry, Johnny Hodges, King Cole, and Coleman Hawkins, on their instruments. There was the memorable “One Sweet Letter from You,” with Hawk, Ben Webster, Chu, and Benny Carter. There was “On the Sunny Side of the Street,” to some still Johnny Hodges’ best side. There was Ziggy’s best playing on records, whenever he appeared with Lionel. Finally, there was the electrifying Hampton, welding the disparate personalities, topping the unified groups, epitomizing an era and its way of joining talents and styles.

Lionel Hampton has always found a large audience for his music, the combination of audiences that made swing. As few other band-leaders after the swing era, he held that combination of audiences. But within a decade after his band made its first appearance, it was no longer of musical significance as a band; its final effect upon jazz — as with most of the important swing bands — was the effect of its soloists, especially Hamp himself.

Written, ironically, after Swing had already died, to be replaced by jazz played only for other musicians, and the idiot-level musicality of early rock and roll.