Editor’s note: The following Comprises Chapter 2 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 1: Infantry Reporter)

_________________________________________________________________________

Training for landing operations began early in October, 1944, in Humboldt Bay, New Guinea. Troops took the long, dusty ride to the beach, then were transported to their ships by small boats. The bay was choppy because of the typhoon season in the north, and many men were violently seasick.

The convoy departed Humboldt Bay, Hollandia, at 1300, Friday, 13 October.

Troops were not excited regarding the movement. The general attitude might be described as: “We’re going to the Philippines— so what!”

(from the Division Record)

___________________________________________________________________________

The story of the American invasion of Leyte is, to me, synonymous with the story of Carmelo Giacomazzo, the woodcarver from Tunisia. It is his glory as much as General MacArthur’s. He did a job, in his own quaint and peaceful way, which saved many lives and helped to make the launching of the Philippines campaign a thundering success.

The Woodcarver is squat. Black curls protrude from under his fatigue cap. He is the opposite of Hollywood’s idea of a soldier. He looks like a wandering Levantine artist and to war he refers as “inglorious trouble.” His hour of glory was a matter of papier–mâché, plaster and a little paint.

The son of an Italian father and a Tunisian mother, Carmelo was born in Brooklyn, but his family moved to Casablanca, Africa, before he was three years old, where he grew up speaking Spanish, French, Italian and Arabic, but not a word of English. His early living he earned as a carpenter in North African harbor towns. He disliked the drudgery of hard labor. “I had good hands,” he says. “I looked at my hands. They told me that I could make things, and more things can be shaped out of wood than fences. My hands like the feel of clay. I swore I should become a woodcarver, a sculptor!”

And a sculptor he became. He modeled in clay, then finished his work in wood. He never married. At the urging of an aunt he came to America.

He arrived in New York on March 1, 1941, an American who did not know a word of English. For five days, broke and hungry, he searched for his aunt. He could not find her. What should he do? On March 5, 1941, he joined the Army of the United States as a volunteer. He was assigned to the 24th Division and fought as a machine gunner in the leprous wilderness of New Guinea, unhappily but well. And then came the day on which the Twenty-Fourth was ordered to tighten its belt for the biggest operation in its history.

The destination was ‘Top Secret.” A great guessing game went on along the steaming mangrove swamps and jungle paths. With the rest, Carmelo asked, “Where are we going?”—

“Borneo,” said the latrine attorneys. “Yap, Halmahera, Mindanao, Celebes.” The Woodcarver wondered and cursed the war.

In the regiments, the battalions, the companies, in the platoons and squads men struck their tents and packed. They checked their weapons and hauled ammunition. Ended were the sweat-stained weeks of waiting, of mopping up the jungles, of digging drainage ditches and standing guard. The men shouted and were alert. They folded their cots and helped the cooks pack pots and pans, and in huge bonfires they burned the refuse that accumulates where masses of men have camped for weeks. The roadsides were lined with barracks bags; the men had stripped themselves to messkit, spoon, jungle knife, poncho, razor, rations, a shovel and their weapons. Someone chanted, “Nobody loves New Guinea…”

Day and night the trucks rumbled to the beaches. Transports hovered offshore. The roadstead was so crammed with ships that at night their anchor lights looked like the lights of some vast coastal city. And with the sound of motors rumbling in his ears, Carmelo saw officers pore over maps, heard them discuss their lack of knowledge of the terrain to be captured on “A”-Day. Difficult terrain? Map trouble? Private Giacomazzo approached a staff officer.

“Let me make you a map of the difficult terrain,” he said.

“A map?”

“Sure.”

“What’s the idea?”

“A relief map,” said Carmelo. “A map of plaster of Paris, papier–mâché, wood— anything. A model map that shows the hills, the valleys— everything.”

Could this obscure private who spoke his English with a Levantine accent be trusted with the top secret of a campaign involving many thousand men? The officers telephoned the Division. The Division said, “Impossible.”

“Let me make that map,” the Woodcarver persisted.

“Who is this fellow?” Headquarters inquired.

“Private Giacomazzo, a sculptor in wood.”

Carmelo argued how good it would be for his buddies to see a model of the battlefield and to see just what to look for and where to go when they assaulted the beaches. More trucks rumbled down to the edge of Humboldt Bay, more jeeps and tractors and guns in an endless stream. Tools of war crammed the wide-mawed landing ships. And the colonels capitulated to the private.

There were some old maps at hand, not very accurate contour maps. And there were the aerial photographs. Could Private Giacomazzo read photomaps?

“I make you that map,” he announced.

And so, after he had rendered an oath of silence, it came about that the Woodcarver from Africa was entrusted with the secret of shore points selected for the American landings in the Philippines.

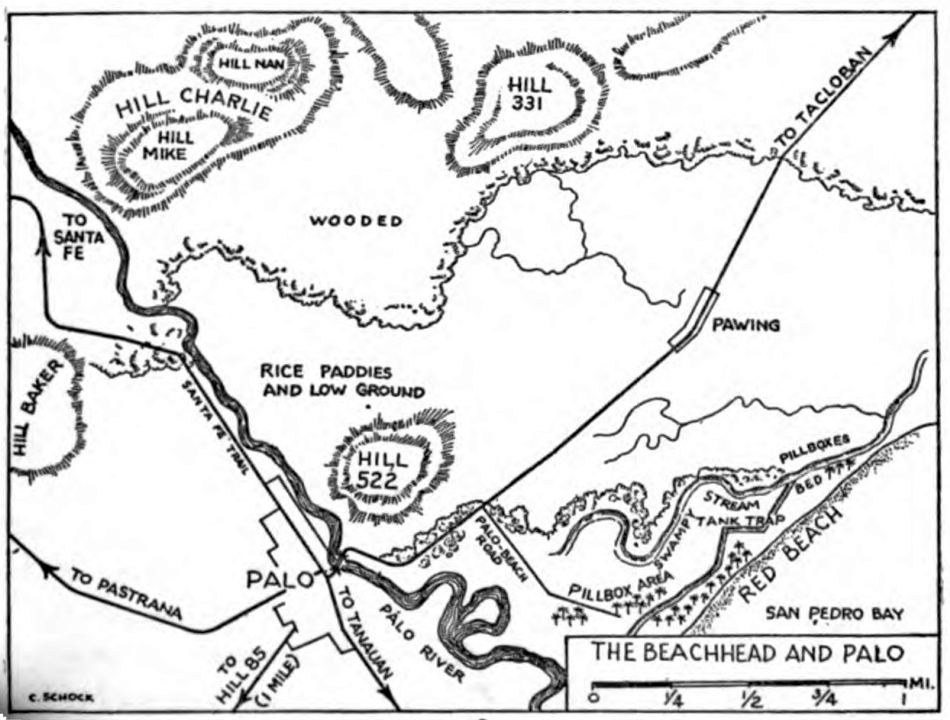

From somewhere Carmelo procured a bag of plaster of Paris. He manufactured his own papier–mâché. Paint he begged from a team of combat engineers— blue for the streams, brown for the hilltops, green for the plantations and the swamps and the jungle-covered slopes. He fashioned a replica of now famous Red Beach. He studied the photographs the officers had given him and what he saw there he put on the map, trails and barrios, a coastal highway, a river, bridges, plantations and rice fields. He ate and lived and rested with his work. He worked with minute care and with pride. A mistake, he knew, might cost the lives of fellow soldiers. And then after five days and nights, he surveyed his work, checked, re-checked, and packed away his tools.

The Division’s commander came and looked at the Woodcarver’s work.

“Giacomazzo,” the general said, “you have made a very good map.”

Carmelo nodded. “I guarantee it with my life,” he said. The general called his staff. They studied the relief. Then other officers came and studied it. And after that, the officers called the sergeants of the assault groups. They all studied the Woodcarver’s map. They still studied it aboard ship as the Division’s convoy steamed northwest.

The Japs on the beach of San Pedro Bay, Leyte, saw a lone American landing craft skirt the sands less than two hundred yards offshore. A rifle shot whipped across the water and a bullet struck the boat’s bow. But the lone visitor continued as if nothing was amiss, its steel ramp jutting like an insolently thrust-up lower lip.

Through a megaphone a Japanese voice roared a single word: “Lunatic!” The nutshell replied with a burst of machine gun fire that sent the Nip observers scuttling over the narrow strip of sand to the shelter of a coconut plantation. The patrolling craft continued, poking about, turning and retracing its course. At intervals a helmeted head appeared briefly over the spy-boat’s bulwark, peered shoreward and slipped from sight.

That was in the early afternoon of October 19, 1944.

Japanese machine guns barked at the unwonted stranger. There followed the sullen thump of mortars firing. Soon artillery joined in punching geysers out of the sunlit sea.

With bullets striking a rapid tattoo against its rust-streaked side the patrol craft zig-zagged in almost waggish unconcern. Its machine gun spat lead into the fine gray sand. That kept the puzzled enemy away from the water’s edge. But despite the near-misses of sporadic shellfire, the boat refused to leave the inshore reaches of San Pedro Bay.

Aboard the foolhardy cockleshell the helmeted man seemed satisfied. Lieutenant Edward F. Roof of Escabana, Michigan, derived a mirthless joy from his role of target for Jap gunners. Draw fire: that was what he wanted— fire that would help him to locate the hidden gun positions of the invasion shore.

“What’s the use o’ worryin’…”

His humming amid the outraged clamor of Jap weapons reassured him. As long as the craft was afloat under him it would divert the Jap gunners’ attention from the water. For in the water, between the landing craft and the shore, men were swimming, probing for underwater obstacles and mines.

The bold swimmers were scouts, the stripped and silent pathfinders for the mechanized amphibious assault. The apparent suicidal impossibility of their mission made it a success. And after two hours of it the spy-boat maneuvered between the shore and the swimmers, picked them up, streaked for the offing, its rear end chugging gas in the direction of the baffled hunters.

Our naval barrage started at 0610, 20 October, 1944.

Assault waves, already loaded in LCVP’s, were swung over the side in a matter of minutes. The sea was smooth and a brilliant sun beat down. The expected air attacks failed to materialize. All assault waves crossed the Line of Departure on schedule. As they raced toward Red Beach the naval barrage lifted, and LCI’s blasted the shoreline with rockets. Dive bombers delivered a final blow at the defenses just before the landing craft hit the beach.

The Division landed with two regiments abreast on a 3000 yard front. The 19th Infantry was on the south, and the 34th Infantry on the north. It soon became apparent that the naval and air bombard ment had not been completely effective….

(from the Division Record)

Scared? Not exactly, but scared, anyway. You go to bed early with the thought, “… let tomorrow take care of itself.”

Reveille sounds through the ship at 0300. You stumble around in the jam-packed hold and get into your clothes. Then you head for the chow line. The sea is glassy calm and under the stars you see the silhouettes of ships and landing craft as far as the eye can see. Off to port looms an inky shoreline, still miles away.

You eat your breakfast in the heat of the blacked-out hold. Eerie red lights gleam overhead. With zero hour near, new men have little stomach for food. But the old hands are not concerned with zero hour— not yet. They are griping, “Look, the belly-robbing bastards, D-Day and no fresh eggs for breakfast.”

After that there is little talking, little moving about. You brush your teeth and then shove the toilet articles into your pack. You make sure your canteens are full of water and you give your weapons a final check. You have a little trouble finding a good place in which to carry your grenades. Then you lie back and smoke and rules be damned.

Old soldiers don’t think. You recognize them by their “GI-look.” If they think at all they don’t show it. But the battle virgins do. One is looking hard at a picture of his mother. Another is wondering if he will see the stars tomorrow night. And still another may be thinking, “When I get it, my wife’ll be putting the kids to bed. She will brush her hair in front of the mirror and know nothing.” Some wise guys are so nervous that they try cracking jokes. But most are quiet. “If you have to get it,” you figure, “let it be a clean one— no jagged stuff in the guts.” Be sure your rifle is loaded. Be sure your safety is off when the ramps go down.

Dawn is in the offing. You go on deck. The rails are crowded. You have your gear ready to wrap around you and head for shore. Not that you are in any hurry. Through the slow minutes you hear the planes roar toward the beaches. You stand and look, and there’s your beachhead far off on the port bow— a crescent of sand, an expanse of palms, and beyond them the jungle-clad mountains. You see the cruisers and destroyers glide inshore and open up with rough treatment for everything that’s dug in and waiting over yonder. The big battlewagons add their thunderous voices and you feel strong and elated. You see the planes bombing and strafing over the plantations and the swamps and you see the flame and the smoke. The whole beautiful morning is filled with continuous, rolling thunder.

You see the assault platoons line up on deck and you grab your rifle and go where you belong. Your sergeant is not wasting words. You clamber into your landing craft and you hit the sea. As the water buffaloes slowly circle their mother ships you suddenly find yourself saying, “What the ‘s the matter, why don’t we go in?” The dangling cargo nets leer at you. The transports hovering all around you seem to look like tired beasts who’ve done their stint.

There is a minute’s interruption. A Jap bomber has sneaked in low from the sea and is heading for the ships. Navy gunners go into action. The Jap sails out of reach of the ack-ack screen and circles the convoy.

Signals flutter and the first waves head shoreward. Soon you, too, are on the way. You crouch low between the wall-like sides of your craft. The rocket ships have moved in and the rockets scream shoreward and you wonder aloud, “How in hell can any thing stay alive on that beach?” You listen to the firing and you watch the coxswain in the stern, his face composed and staring stonily ahead. You hear the invisible water foam past the bucking ramps. The assault run is long. There are still a couple of thousand yards to go.

You risk a peek at the shore. The beach is full of landing craft and men and motion. Already boats head back carrying the first casualties of the invasion. The first waves get ashore with small loss, but the succeeding waves get it hard. There is no thought that you might be the next man on the litter. It always seems to happen to somebody else.

Just then Lieutenant Art Stimson of Houston brings out a Texas flag and waves it from the stern. The coxswain’s eyes are narrow slits now, his sunburnt face thrust forward, his hands tight around the spokes of the wheel. Jap artillery is shelling the beach. Jap mortars and beach guns meet the incoming boats.

A large landing ship is heading out to sea, smoking from stem to stern. Several craft carrying 19th Regiment assault groups are hit and sunk. They heave like living things in pain, stern high, and there is a melee of bobbing heads in the water. “C” Company’s commander is killed. A direct hit wipes out a whole squad still more than a thousand yards offshore. Cannon Company loses two section leaders, a platoon leader and some of its headquarters personnel.

Jap artillery hit four of the larger ships. A liaison officer was blown to smithereens. Three Division Headquarters officers were wounded by a shell which sank their craft under their feet. Another shell blew the Division Quartermaster and his aide clear out of their stateroom.

Sergeant Joe Babinetz of Kingston, Pennsylvania, was riding in a boat when a direct hit smashed the ramp. In a matter of seconds tons of water filled the boat. Debris flew high. Wounded men screamed in the wreckage.

“Get off, get off the ship,” Joe Babinetz shouted.

Men discarded their packs and helmets and dived into the sea. Babinetz, wounded by shrapnel in head and chest, remained aboard. He saw another wounded man threshing in the bottom of the waterlogged craft. The man was drowning. Babinetz, bleeding fiercely, dived. He yanked the drowning comrade to the surface. A Jap mortar shell exploding in the sinking wreckage tossed a life jacket into Babinetz’ face. He grasped the life jacket, secured it around the wounded man and slipped him overboard to await the rescue patrol.

The concussion of three mortar shells striking another landing boat ripped the steel and hurled its occupants through space. Lieutenant James Russell of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, felt himself thrown upward by the blast. He hit the water, badly shaken, and strove to regain his bearings. He saw the sinking boat. Then he heard someone yelling for help.

“Stop your yelling,” James Russell shouted.

With a few strokes he reached the sinking craft. There he saw a mangled soldier squirming under water, pinned fast by the wreckage. His lifebelt, as well as the lieutenant’s, had been deflated by shrapnel. Russell slipped into the sinking boat. He freed the wounded man and dragged him out into clear water. Seconds later the boat sank. Machine gun bullets snarled close overhead. The water was a-churn with undertows and whirlpools created by the rush of shore-bound ships. Russell struggled for naked life. But he held on to the now unconscious soldier, kept him afloat, dodging the pull from whirling propellers.

Through confusion and men adrift in the sea, your boat approaches the beach. There is a noise a few inches from your head as if a gang of shipyard johnnies were belaboring the boat’s outside with hammers. You see the coxswain’s mouth wide open and you tighten your helmet. The keel scrapes sand. There is the jerk you get when a fast-going train stops suddenly. The ramp clatters down and you run out. You wade through hip-deep water. You fan out, away from the others. You dash across the narrow beach. You run as you have never run before. You run for the cover of coconut palms crippled by the bombardment. You flop down on your belly, not taking time to break your fall with your rifle. Then you see a lower spot nearby, roll into that. You rest a minute. After that you look around with your chin firmly in earth a-crawl with ants.

As LST’s cramful of tanks and artillery churn shoreward it is discovered that there are only two slots where the larger landing ships can beach. It looks as if someone bungled in the planning. But there is hope that more will get in over the shallows at high tide. This hope is false. Out of seven tank landing ships in the assault, only two make the beach and hang on there by the skin of their ramps. Two others, unable to find a fit landing place, are driven away by shellfire, and three more are cruising angrily off shore and do not make the run until much later. Battle fate would have it that the landing ships that retired took most of the tanks and artillery with them.

The smashed Jap forts and tunnels fronting the beach look like monstrous teeth smashed by some mad dentist. The tops of most palms have been shorn off. You look for dead Japs and find none. You see some of our own dead sprawled in the sand like careless sleepers. Shredded palm fronds litter the waterfront. Men are milling around the beach; a lot of supplies are piling up, and more come ashore in a violent torrent. You hear much firing but not a shot is aimed at you.

You change your mind when a rifle report that is not yours rings in your ears simultaneously with the strike of a bullet three feet away. You wish you could crawl into the earth like a worm, but what you do is turn your head to find out where that shot came from. You have a powerful urge to dig a foxhole, and that is what you do.

The sun is hot and the sniper fire is just as hot, and the machine gun fire makes your belt feel too loose around your hips. You become accustomed to the sniper fire after a while, but not to the digging. Digging a hole while hugging the ground at the same time. As long as you’ve been in the Army you resented digging. So you don’t hurry, even though you feel that by not digging deep enough fast enough you might be helping along a bullet tagged for you. You find that there is water a foot below the surface. You mutter an obscenity and stop digging. You reach for your rifle, crawl a few feet to ground that is a little higher and start looking for a target. The malevolent crashing of mortar shells on the beach makes you wish you were a million miles away.

You see one of your own mortar squads land and you see the men rush forward to go into action. You know the fellows. They sweat under their loads and their faces are distorted as if by great pain. Halfway across the beach a Jap shell explodes. You see one man’s side ripped open and a look of unbelief on his face and his hands pressing down to keep his guts from spilling. It is a beastly thing to happen in bright sunlight and under a blue sky. It takes the boy more than a minute to die. The squad leader, too, has been hit and the others are clinging to the ground, face down, their mortars useless. Then you hear a rough voice say,

“Come on.”

The soldier who gets up and who makes the squad get up and pick up their weapons is Sergeant Merlin F. Martin of New London, Iowa. A pretty young wife named Bertha is waiting for him ten thousand miles away. But Sergeant Martin’s chin is out and he is too busy to think of his wife just then. He rallies his men by setting an example. They dash after him into the shade of the palms. He points at a group of shell holes with overhead clearance.

“Set ’em up,” he tells his men. “Watch me for fire orders.”

With that he crawls forward for better observation. Three minutes later his mortars are lobbing high explosives onto the maze of Jap pillboxes and spider holes a couple of hundred yards away.

Or take Arthur Kmiecik whom we used to kid about his tongue-breaking name. Twenty minutes after he waded up the beach with his machine gun, his squad was pinned down on open ground by solid bands of lead pouring from a pillbox. Kmiecik is from Milwaukee; he reacted like a bull to a scarlet cloth. Together with another volunteer he picked up his gun, cradled it in his arms like a baby and went straight toward the Jap emplacement. Then he set down his gun and silenced the Nips at point blank range. Other Japs spotted him and soon mortar shells burst perilously close. Kmiecik was seething.

“Follow me,” he told his squad.

Off they went, gunning for the yellow mortar men.

Elsewhere things were not going so well. The assault companies of the 34th Infantry had landed 300 yards farther north than planned. And the 19th Infantry Regiment— which had done its first fighting in the Civil War and there earned the name “Rock of Chickamauga”— was also deflected to the north and landed almost on top of the Thirty-Fourth. As a result the enemy was dangerously strong on our left— or southern— flank. He sat solidly athwart the approaches to the day’s main objectives; dominating Hill 522 and the town of Palo. Both were more than a mile to the south and east.

Companies of the Thirty-Fourth lay glued to the beach, loath to budge under murderous fire. Here and there a curse, a startled cry arose as bullets shredded combat packs strapped to immobile backs. Lieutenant Barrow of “Item” Company half rose to his knees, then stood up, pistol in hand.

“Let’s go, men,” he urged, “we can’t stay here forever.”

Death stabbed through him in an instant. A clean shot through helmet and head. His fellow officers had lost control. The men clawed harder into the sand, and you could hear their bodies groan.

Landing with the fifth assault wave were bulldozers and Colonel A. S. Newman of Clemson, South Carolina. Newman commanded the Thirty-Fourth. Stocky, red-headed, deliberate, the colonel sized up the situation— the bunched-up men; the enemy’s skillful crossfire; the crack of snipers’ rifles from the palm tops; the mounting confusion of piled and scattered supplies and unused weapons. The Colonel rose from his crouch. Death be damned! He stood erect, a middle-aged chunk of character that mastered fear. He walked straight toward the sounds of firing. He waved his companies forward. “Get the hell off the beach,” he roared above the laughter of automatic weapons. “God damn it! Get up and get moving. Follow me!”

The men responded. The officers seized the opening to rally their units forward. The specter of panic was trampled to death under “Red” Newman’s combat boots.

The companies advanced. They tackled five earth-and-palm-log pillboxes along a streambed less than a hundred yards inland. Here, Captain Wai, regimental intelligence officer, was killed. A medical corpsman running to the aid of wounded in a palm grove had his midriff shot away. Three bulldozers landed and with them units of the Division’s Third Combat Engineers. Their job was to build dirt ramps across a huge tank trap which hitherto kept vehicles from leaving the beach. Rhinoceros-like, the bulldozers charged into the palms, their raised blades shielding their drivers.

Meanwhile the 19th Infantry assault waves pounded forward in their southern sector of the beachhead. After four hours of fighting one company had progressed five hundred yards inland. Another met a tank ditch, emplacements, machine guns, mortars and field artillery only fifty yards from the water’s edge. The battle moved in a grim patchwork of disorder, with platoons and squads and foolhardy individualists striking out on their own. A soldier cracked and yelled that he was being chased by wolves. “King” Company became disorganized because its command boat broke down on the shoreward run. One platoon entangled in the fray did not establish contact with its mother team until the following day.

But one after another Jap snipers toppled out of palms like sacks of meal. One after another the Jap emplacements were reduced, their crews destroyed. Private First Class Frank B. Robinson of Downey, California, made himself a one-man platoon. He crawled atop a stubborn pillbox and dropped three grenades through its port. He then reached down and pulled the barrel of the Jap machine gun out of line, burning his hands in the process. A little farther he came upon a cursing flamethrower man. The fellow had his weapon aimed at an enemy dugout, but the flamethrower refused to ignite. Robinson crept to the flank of the dug out, picking up discarded Jap newspapers on the way. He held a match to the paper and threw the burning bundle in front of the dugout. The flamethrower fired through the flames and the flames ignited its charge and from the dugout came a screech and the smell of burning flesh. Already Robinson was on his way to another Jap stronghold which had bothered him.

“Baker” Company of the Nineteenth charged fire-spitting emplacements with grenades. A number of its men fell under Nip lead, among them the Executive Officer, Lieutenant Buck. “Dog” Company lost men at the hands of the same Jap warriors. Sergeant Beslisle of Headquarters Company, too, met death at this spot. “Charlie” Company had landed and was immediately pinned down. “Able” Company was split by fire upon landing. The men of “Easy” Company spotted a group of 75’s blasting away at landing craft offshore; they knocked out one of the guns with bazooka rockets and captured two more. “George” Company’s men killed eleven Japs of a Teishintai suicide platoon, but fifteen of its men were hit in the first few minutes of a subsequent encounter.

Wilford R. Stone of Watervliet, New York, saw the scout of his squad drop badly wounded thirty yards in front of a Jap fortification. Undaunted, he edged through machine gun and mortar fire and carried his wounded friend to safety.

Chester Ledford of Perry, Missouri, saw a company officer lie helpless in fire from two enemy emplacements. Together with Herman Gendron of Detroit, he dashed into the killing zone and dragged the wounded officer to cover.

And there were others who gambled their lives to save the lives of hit buddies during that merciless day; Norbut Maier of Cincinnati who rescued two wounded begging for an aid man when no aid man was near; Ted Nelson of Barnard, Missouri, who dragged three wounded out of the path of a heavy machine gun; Irwin Duane of Sacramento, California, who saved a sergeant’s life by swift, accurate fire; and Leo Uzarski of Los Angeles, whose ankle had been smashed by Jap shrapnel, but who nevertheless heeded a frantic call to save three from bleeding to death.

The fighting moves inland in tortuous eddies. You note by the sun that it is early afternoon. The first self-propelled guns and the first jeeps have cleared the beach to join the pioneering bulldozer men. You watch them go and you feel the sun’s heat strike through your helmet in liquid hammer-blows. You feel it even in the erratic shade of the broken palms. You have become indifferent to things. You are too numb to feel fear. All you hope is that no mortar shell will tear off your leg and leave you alive. Your canteens are empty. Green coconuts knocked down by the shells are everywhere. You chop off the end of one with your machete and drink the milk. It tastes good. While you drink your eyes fall on some dead. The Japs are twisted shapes with twisted faces. Most of your own dead lie as if they were asleep. You wonder why that is so, until you see an American whose eyes have burst out of his face. The horror does not halt the little things of life. You pee and you wipe your nose. You grab to feel if that piece of soap you pocketed that morning is still there.

A small group of men is wading up from the beach. You pay no attention to them until you see some sweating, bare-torsoed GI’s tear away and wriggle hastily into their shirts. You hear a sergeant bluster, “Button up, button up,” and for a moment you think he is crazy.

The small group of men is moving steadily up from the water’s edge. They cross the tumultuous strip of sand, and then you notice that one of the group, the leader, wears no helmet. He wears a cap and he is smoking a corncob pipe. He walks along as if the nearest Jap snipers were on Saturn instead of in the palm tops a few hundred yards away. You stare, and you realize that you are staring at General Douglas MacArthur.

The General is trying to find the Division command post With him is his Chief of Staff. They stop to ask a sergeant the way. The sergeant doesn’t know. He is too busy to bother with gold braid. Just then Lieutenant Art Stimson— he of the Texas flag— comes running along the rim of the coconut plantation. He grins a salute and takes the generals in tow.

A few yards away you hear a begrimed soldier ask: “Who’s those two guys?”

“They’re the generals,” somebody replies.

“What the hell are they doing up here?”

“Damfino … they just come around, I guess.”

A correspondent from the Chicago Tribune buttonholes you and says that he has something to show you. You figure that he wants to show you MacArthur. But his interest is in a Jap pillbox that has been knocked out twice but insists on coming back to life. It’s hidden in a clump of bamboo on the beach road to Palo. It has been treated with grenades, and flame-throwers. A bulldozer completely buried it. Tough Japs inside it sing Japanese songs. They work like moles to clear the ports, and suddenly their machine gun comes back to life. From a distance you watch the bulldozer approach like the crack of doom. Riflemen cover its progress. Then your squad leader throws a handful of dirt at you to catch your attention, and when you look, he says, “Come on.”

And by-and-by you kill your first Jap. You see him struggling out of a pillbox full of smoke and you see him arm a grenade by tapping it on his helmet and his eyes are on you. You fire. The Jap lets go his grenade; his face is a pinched grimace and he flops around like a caught fish. You shoot him again, point blank, seven times, and he is still, and you quickly shove a new clip into your receiver.

A driver runs by shouting to everybody that Jap bullets have disabled his truck. But some way off Corporal Irwin Duane is still at work and he says nothing. He is the gunner of a self-propelled piece of artillery, an SPM— M8. He is busy putting his shells into a pillbox, mixing earth, palm logs and Japanese flesh into one hash.

Another company commander is killed. The platoons are scattered and lose contact. Captain Louis Berdami of New Orleans stands up and takes charge. His quick thinking saves the whole right flank of the attack from bogging down. But Berdami, too, is killed in action.

Sergeant Clifford McGowan of West Concord, Minnesota, sees his company in dire trouble from enemy machine gun nests not far ahead. He knows that staying there will cost lives. So he crawls forward inches below the trajectory of the bullets. He crawls to within seventy-five yards of the Nip gunners, determines their exact position, then directs his mortars which soon put an end to the nest.

Private Albert M. Baskin of Baltimore sees a Jap in a pillbox take pot shots at his company commander. The officer is unaware of the source of bullets slapping the ground nearby. Baskin runs up to knock out the Jap, is wounded but keeps going. He kills the Jap. The enemy, a first lieutenant, died smiling.

Another stronghold is holding up a whole platoon. Sergeant Cameron E. Hale of Port Huron, Michigan, wades through a swamp and flanks the enemy position. Fire from his automatic rifle forces the Japs to duck. This enables the platoon to rush in and finish the job, with cold steel.

One hundred yards from Red Beach a burst of shrapnel lacerates the leg of Sergeant Ignazio Amato of Brooklyn, New York. Aid men rush to evacuate him to the ships. Amato’s face is ashen. He bites his lips, shakes his head, continues to lead his riflemen. The Japs have killed a guy he liked. Amato’s charge is a limp. Blood is squelching from his boot. But the Japs die.

Most of us have no love for first sergeants. We all have cursed them as fat-assed tyrants. But there at the edge of San Pedro Bay, First Sergeant Russell T. Edberg, of St. Paul, Minnesota, was worth his weight in Samurai swords. A camouflaged machine gun neutralized his assault battalion and Edberg does not like it. He peers around but cannot see the gun. He stands upright and blusters forward until he sees the gun. He then shoulders back, summons a volunteer. Together they carry one of their own machine guns to the threshold of the obstinate bunker. Scores of rounds ripping through the ports fill the fort’s interior with prancing ricochets. The Japs fall silent. Edberg grins a Viking grin.

As the fiery sun dipped westward, elements of the Thirty-Fourth attacked across an open swamp. Waist-deep in slime and rottenness the tired men toiled forward, paced by the thumping of their mortars. Another force of their regiment attained the high way which links Palo with Leyte’s capital, Tacloban. Red Beach lay more than a thousand yards to their rear. Nearby sprawled clusters of palm and bamboo huts. A few of the huts burned down, but most seemed strangely undamaged by the hail of bullets. Pigs rummaged there among the reeking stilts, and a lean dog howled. The native inhabitants had fled to the hills. This ghost community was the village of Pawing.

On the southern sector of the beachhead the “Rock of Chickamauga” slugged toward the town of Palo and Hill 522. This fighting machine ran head-on against unyielding fortifications blocking the beach road. Assaults that day failed to crack the defense.

The men were exhausted. Darkness was closing in and the night was streaming with stars. The battalions dug in. Between eruptions of explosives the still air was pregnant with the sibilant voices of mosquitoes and the chirping of myriads of cicadas. The men in their holes chewed cold rations and wondered. All battalions were there but one: the Nineteenth Infantry’s First, Lieutenant Colonel Zierath, commanding. Along the perimeters men harked to the crash and thunder of an artillery barrage. Artillery had landed in force and the batteries filled the evening with the whirr and the moaning of flying steel. Along the perimeters men asked, “What are they firing at? … What happened to the First Battalion?”

On Hill 522, hulking saturnine above the banks of the Palo River, lay the answer.