Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Some Famous Privateers of New England, by Ralph M. Eastman (published 1928).

A ship’s boy who was a prisoner aboard a British brig-of-war was standing one day at the rail peering intently at a speck of white which evidently was heading toward him, when suddenly his hat went up in the air and he began to sing and dance. When asked by the surprised sailors who stood near by as to the cause of his rejoicing, he replied with the utmost confidence:

“My master is in that ship and I shall soon be with him.”

“Your Master! Who the devil is he?”

“Why, Captain Haraden. You don’t mean you never heard of him? He takes everything he goes alongside of, and he will soon take you.”

The British captain, when informed of these remarks, sent for the boy and had him repeat what he had said. During these precious moments, the General Pickering had approached within hailing distance and across the gale, in stentorian tones, came the order from Captain Haraden: “Haul down your colors or I’ll fire into you.”

The skillful seamanship of the American had put the British vessel in such a position that her guns could not be used to advantage, and after a brief and futile fire from her deck swivels and small arms she was obliged to haul down her colors. Thus was one more prize added to the many already standing to the credit of the intrepid Haraden.

This incident illustrates how Captain Haraden was regarded by those who served with him, and indicates how he became one of the most famous of American privateersmen. Easy-going to a fault when ashore, he was swift as lightning and sure as death in his grasp of essentials when afloat, and his coolness and audacity seemed never to forsake him. Again and again he was able to capture enemy ships by sheer nerve, without firing a shot. In fact, so great was the belief of his crew in the infallibility of his judgment that, if he picked up a glass to sight a vessel and ordered the helmsman to steer for it, the word often went around that another prize was certain.

On one occasion, while in command of the General Pickering, he fought for over four hours a “king’s mail packet” bound from the West Indies to England. She proved a tough customer, for packets carried about 20 guns and complements of from 60 to 80 men, and Captain Haraden was finally forced to haul off to make repairs. Learning to his chagrin that he had but one charge of powder left, he tried the desperate plan of frightening his antagonist into surrender. Having loaded a gun with his last charge, and double-shotted it, he again ran alongside the badly cut-up but unconquered enemy and roared: “I will give you five minutes to haul down your colors. If they are not down at the end of that time, I will sink you, so help me God!”

The dread of another broadside at less than pistol range, combined with the sight of the determined-looking Haraden and his crew of half-stripped and bloody privateersmen, standing with lighted matches at their guns, was terrifying even to the plucky British captain, and before Haraden, standing on the quarter-deck with watch in hand, could count “four,” down fluttered the packet’s colors. When a prize crew from the General Pickering went aboard the captured vessel, they found the aged governor of the island from which the ship had sailed seated in an armchair on deck with a heavy blunderbuss at hand. A bullet had passed through his cheek, but, in consequence of his lack of teeth, it had gone out through the other side without causing a disastrous wound. Though this had happened early in the engagement, it had not stopped him from continuing the fire from his blunderbuss until the ship was surrendered.

Jonathan Haraden had had considerable experience on the sea before being given command of the General Pickering. He was born in Gloucester, and as a boy went to work for George Cabot, a Salem merchant, who was later president of the Hartford Convention and was great-grandfather of Henry Cabot Lodge, distinguished United States Senator from this State for so many years. As was the case with many Salem boys, desk and counter had no attractions that could compare with the lure of the sea; so it is not surprising that by the beginning of the Revolutionary War young Haraden had risen to a command in the merchant service.

With the outbreak of war, he was appointed lieutenant under Captain Fisk in the sloop Tyrannicide, belonging to George Cabot’s son Richard, which was one of the two small vessels placed in com mission by the Massachusetts Colony as state vessels of war. Haraden distinguished himself in the various engagements in which the Tyrannicide took part, and later was promoted to the command of this modest vessel with the formidable name. However, he preferred greater freedom of action, and obtained his release from state duty after the sloop was burned during the Penobscot expedition to prevent her falling into the hands of the enemy. He was soon offered command of the General Pickering, a Salem merchant ship of 180 tons which was fitting out as a Letter of Marque. Mounting 14 six-pounders and carrying 45 men and boys, she set sail for Bilbao, Spain, in April of 1 780, with a cargo of sugar. On her way across, she was attacked by a British cutter of 20 guns, but her captain beat off his antagonist and continued on his course after a running fight lasting about two hours. Proceeding to the Bay of Biscay, the General Pickering overtook, after nightfall, the British privateer schooner Golden Eagle, with 60 men and 22 guns. Laying alongside, Haraden exercised his consummate ability to bluff.

“This is an American frigate, sir,” he shouted through his speaking trumpet as he sprang to the side of his vessel. “Strike, or I will sink you with a broadside.”

The darkness prevented the captain of the schooner from judging the size of the enemy, and Haraden’s “bluff” evidently worked, for the British vessel was surrendered without a shot. At dawn the next morning, as the Golden Eagle, with a prizemaster aboard, approached the harbor in company with the General Pickering, a suspicious-looking vessel appeared, nosing her way out.

“What ship is that?” asked Haraden of the English captain whom he had taken aboard his vessel from the prize.

“That is the Achilles, and she carries more than 40 guns and has a crew of 150 men,” was the reply, accompanied by a chuckle as the speaker thought what an easy victim Haraden would be to so powerful a privateer.

Haraden scrutinized the approaching vessel through a spyglass and then, laying it down, coolly observed, “She is a bit bigger than we are, but I shan’t run from her.” To the officer of the deck he said, “Keep the ship on her course, sir.”

The wind died down so that about dusk the Golden Eagle had drifted far to leeward and fell an easy prey to the Achilles, which put a prize crew aboard and then beat up to windward to engage the General Pickering. It was now dark, and the commander of the Achilles, feeling sure of his prize, postponed engaging until the next morning. Haraden himself was quite as confident, and calmly sought his hammock and went to sleep, after ordering the officer of the watch to call him if the Achilles approached. He was aroused at daybreak by the report that the Achilles, with her crew at quarters, was heading for the Pickering, and he, therefore, ordered his men to their guns.

As he had put a number of his men on board the Golden Eagle as a prize crew, he now had but thirty left to man his vessel. In his extremity, he harangued so eloquently the sixty prisoners whom he had taken from the Golden Eagle that a boatswain and ten men offered to serve with the American crew.

“Now, men, don’t throw away your fire; be firm and steady and we will take her,” said Haraden as he made a tour of the decks, adding, “Take particular aim at their white boot-tops.”

In the meantime, the General Pickering had been cleverly manoeuvred between the land and a line of shoals, so that the Achilles, when she closed with the American vessel, would receive a raking broadside. Thousands from the city of Bilbao thronged the shore front on this morning of June 4, 1780, to witness the exciting fight between these two privateers. Fishing boats, cutters, rowboats, as well as large and small sailing vessels filled with spectators, were so crowded together along the quays and to within a short distance of the battling General Pickering, that an onlooker reported that it seemed like a solid bridge of boats, across which a man might have made his way by hopping from one gunwale to another. Robert Cowan, who witnessed the fight, stated that the General Pickering, compared to her antagonist, looked like a long boat by the side of a ship. Another onlooker said that Haraden fought with a determination that seemed superhuman, and although in the most exposed position, where the shot flew thick around him, he was all the while as calm and steady as if he were amid a shower of snowflakes.

Haraden so placed his vessel that the Achilles was exposed for over two hours to a raking broadside fire before she could work into the position she wished. The sugar with which the General Pickering was loaded made her so low in the water that the towering Achilles found it difficult to sweep her, while the General Pickering‘s low broadsides again and again swept the decks of the enemy with fearful effect. It seemed as if Haraden’s composure increased with the deepening peril, and the more critical the situation, the more consummate was his skill in meeting it. Amid the rain of round and case shot, he appeared as much at ease as if he were safe in his Salem home. As the fire from the American swept the British vessel, cheer after cheer rose from the flotilla of boats watching the fight and from the thousands of Spaniards who packed the headlands. A most interested spectator of the conflict was the British prizemaster aboard the Golden Eagle, who inquired of the American prizemaster, John Carnes, who, in his turn, had been captured, what the strength of the General Pickering was.

“She carries about 45 men and boys and 14 six-pounders,” was the reply.

“You’re a liar,” replied the astonished Britisher, with an oath; for he could not believe that a vessel so lightly armed could do such damage to the powerful Achilles.

After more than two hours of fierce fighting, the Achilles had been hulled again and again, her rigging was tattered, and her masts splintered so that she was almost unmanageable. Realizing the condition of the enemy, and learning that his own vessel was running short of ammunition, Captain Haraden resorted to the expedient of cramming the muzzles of his guns with crowbars. It is said that these flew like a flight of huge iron arrows, “made hash” of the enemy’s decks and drove the gun crews from their stations, doing so much damage generally that the Achilles decided it was time to seek safety in flight. The heavily laden General Pickering hastened in pursuit, Haraden offering his gunners large sums if they could carry away one of the enemy’s masts, or otherwise disable her. Being no match in speed for the Achilles, however, after three hours of chase the American vessel sorrowfully headed about for Bilbao.

On his way back to the harbor, Haraden recaptured the Golden Eagle and, upon landing, one would have thought he was the popular matador of a bull fight. The crowd swarmed to his landing place, caught him up, and carried him through the streets at the head of a triumphant procession of thousands. Numerous dinners and public receptions followed to honor this hero of one of the most spectacular engagements in all privateering annals. In fact, on account of the number of spectators who witnessed the battle, it has often been referred to as the “Kearsarge-Alabama fight of the Revolution.”

The indomitable Haraden was destined to take part in many more exciting adventures before his death in Salem in the year 1803. During a voyage from his home port to France, a great English ship of the line came upon him at daybreak and escape seemed almost impossible. However, manning his sweeps, three of which were sheared off by a shot, the Yankee craft was rowed out of danger. Haraden was always ready to fight “at the drop of the hat,” but had wisdom enough not to risk his vessel and the lives of his men in an action when the odds against him appeared insurmountable.

The General Pickering, under his command, made many voyages between this country and France, bringing back large quantities of provisions and munitions needed by the Continental Army. Later on, his ship was equipped with somewhat heavier armament, which stood him in good stead in two remarkable engagements. In one of these he captured three British ships carrying a total of 42 guns. In the other, he took a brig of 14 guns, a ship of 16 guns and a sloop of 14 guns on their way from Halifax to New York, by combining audacity with superb seamanship and by attacking one after the other so that they could not unite against him.

At another time, in effecting the capture of two exceptionally fast British privateer sloops which had retaken several of his prizes, though not daring to risk action with the General Pickering, he disguised his vessel so that it appeared to be a plodding merchantman. Upon sighting him, these two alert foes set out in chase. Letting the first one come close, Haraden stripped off the painted canvas screens that had covered his gun ports, fired a devastating broadside, and captured the sloop without more ado. It hardly need be said that her consort as well was shortly in the possession of the ingenious Haraden. This is another bit of evidence that the art of camouflage was used on the sea many years before the World War made it so well known.

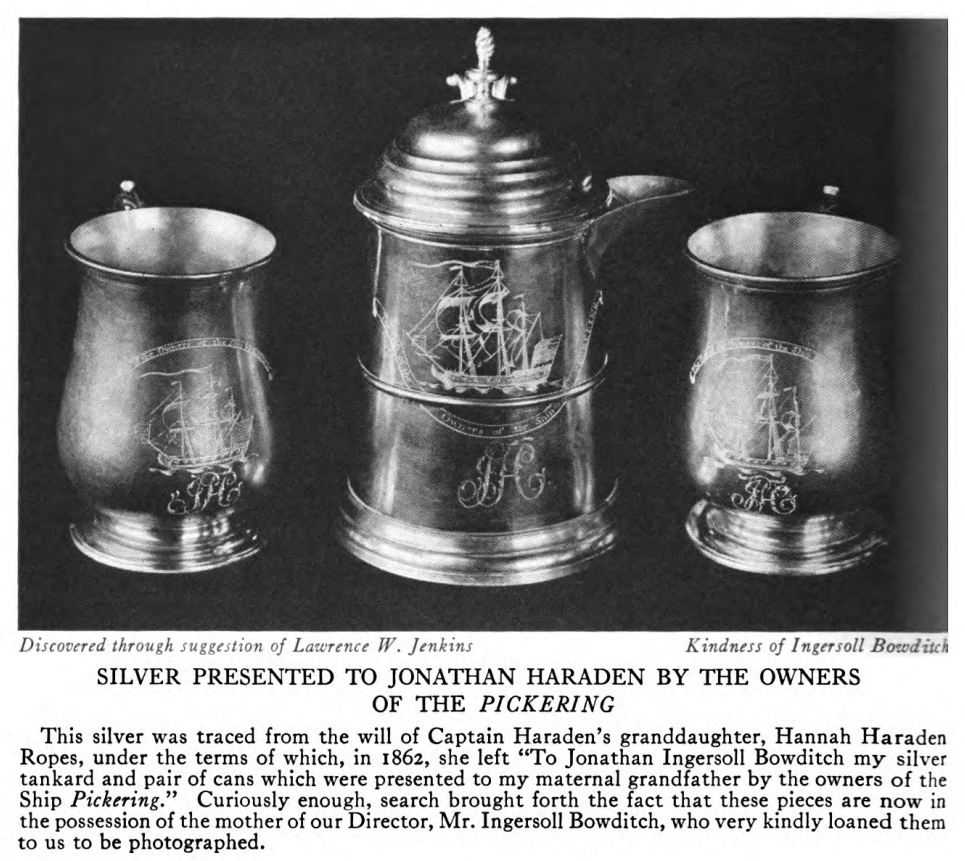

Toward the end of the Revolution, Haraden took command of the Letter of Marque ship Julius Caesar, carrying 40 men and 14 guns, which he handled with such bravery and skill that her owners pre sented him with a massive plate. His descendants treasure a gift of silver received from the owners of the General Pickering, shown in an illustration on another page.

In the Julius Caesar, Haraden fought successfully several engagements against two ships at a time. It is said that after one fight which lasted for over two hours, with neither side being able to gain a decisive advantage, Captain Haraden jokingly described the outcome by saying, “Both parties separated, sufficiently amused.”

During his various cruises no less than a thousand enemy cannon were captured by this splendid seaman, who did far more to win the independence of his nation than many a landsman whose military achievements won the recognition of the government and an honored place in history.

The house in Salem where Captain Haraden died is now marked by a tablet to his memory.

4.5