Editor’s note: The following article by Captain Michael A. Phipps appeared in Infantry, Vol. 74., Number 1 (January-February 1984).

Few events in American history have been written about and discussed more than the Civil War. Yet only a handful of the works on this fascinating chapter from our past are geared to the military professional. Studies of small unit actions (brigades and regiments), especially, are few and far between. And a large percentage of the ones that there are are aimed at the civilian layman — many of them, in fact, are not far from being fiction.

This approach is understandable, because authors must sell books, and the civilian and entertainment markets are certainly more lucrative than the military one. But if the study of past failures and successes may one day allow our combat leaders to accomplish their missions better, then it is imperative that we conduct these studies.

If the Civil War is one of the most written about events in American history, then the Battle of Gettysburg is certainly the most written about event of that conflict. As a matter of record, there have been more studies of Gettysburg than of any other combat engagement in world history. (Waterloo is a close second.) So why another essay on the battle? The answer is simple — few studies have used Gettysburg properly to teach a better understanding of small unit tactics.

The cataclysmic engagement of the first three days of July 1863 offers many important lessons for today’s military professional. But it would take an entire issue of Infantry to do justice to even one day of the battle. The following, therefore, is a study of a portion of one day’s battle — the meeting engagement on McPherson’s Ridge on 1 July in which a Union force consisting of a cavalry division and a division of infantry met a Confederate force of two infantry brigades. There are definite parallels between this battle and a future battle that United States forces may have to fight.

After defeating Major General Joseph Hooker’s Army of the Potomac in early May 1963 at Chancellorsville, Virginia, General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, decided to invade the North. At the time, his army consisted of some 75,000 men divided into three infantry corps — the First commanded by Lieutenant General James Longstreet, the Second led by Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell, and the Third, by Lieutenant General A.P. Hill — and a cavalry division of six brigades led by Major General J.E.B. Stuart.

While historians have advanced numerous reasons for Lee’s desire to invade the North, he himself probably offered the most logical explanation: He wanted to draw Hooker’s army — 95,000 men divided into seven infantry corps and one cavalry corps — out into the open where he could defeat it in detail. He could then threaten a number of Northern cities and possibly the Northern capital itself.

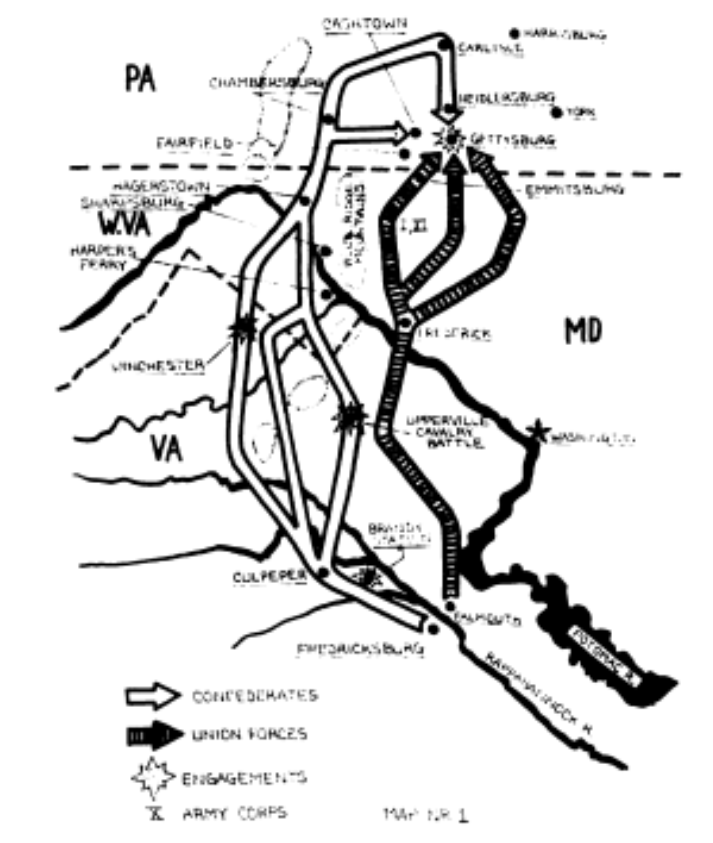

Lee began moving Longstreet’s and Ewell’s corps from their positions near Fredericksburg, Virginia, on 3 June 1963; he directed them to move west toward the Shenandoah Mountains and to concentrate at Culpeper Court House. Lee left Hill to cover the Fredericksburg position and to keep Hooker from moving south against Richmond. Hill was to follow later, after Hooker had begun to move in response to Lee’s movement (see Map 1).

Hooker was aware that Lee was up to something. Concerned that the Confederate commander might be trying to turn his army’s right flank, Hooker ordered his cavalry commander, Brigadier General Alfred Pleasanton, to find out what he could about a Confederate force at Brandy Station. On 9 June, Pleasanton found out — he surprised and almost defeated Stuart’s cavalry division, which had been concentrating in the area before leaving to cover Lee’s northern move. Pleasanton came away from Brandy Station convinced that Lee was preparing to invade the North and passed this on to Hooker.

Hooker was not as certain, but on the 12th he did order three of his corps to move to the west and north to keep Lee from turning the army’s flank. He also knew he had to keep his army between Lee and the Washington-Baltimore area. Hill, realizing that Hooker was moving after Lee, left Fredericksburg and started for Culpeper Court House on the 15th. Hooker’s last infantry corps left the Union camps near Fredericksburg the same day. On that day, too, Ewell’s corps scattered a 9,000-man Union force at Winchester and his lead units crossed the Potomac.

By 17 June Lee had concentrated his army in the Shenandoah Valley. Hooker continued to move his corps to the north and west to block any Confederate move out of the Valley, and he sent strong cavalry formations into the Bull Run Mountains to try to find Lee’s main body. Stuart met the Union troopers and turned them back after a series of vicious cavalry actions at Aldie, Upperville, and Middleburg between the 17th and 21st of June. But while the cavalry reports gave Hooker a pretty good idea of Lee’s location, he still was not certain about Lee’s intentions.

Meanwhile, Lee decided to hurry his move to the north, feeling sure that Hooker would not interfere with his move because of Hooker’s known conservative style of leadership. He did not know that Hooker had started moving his corps to the north, but this probably would not have made any difference in Lee’s plans at the time. He kept two of Stuart’s cavalry brigades to guard the Blue Ridge Mountain passes — Ewell had a cavalry brigade with him — and let Stuart take the other three cavalry brigades to screen the army’s move north of the Potomac. (Unfortunately, Stuart took wide latitude with his orders and decided to ride completely around the Union army. Apparently, Stuart felt that his presence in Hooker’s rear would cause the Union commander to concentrate against him, thus letting Lee move almost unmolested. This did not happen. Stuart soon lost contact with both armies, and he did not rejoin Lee until 2 July.)

For the week between the 17th and the 24th of June, Hooker made no major move, despite the steady flow of intelligence into his headquarters from his advanced cavalry units. By the 24th, in fact, Ewell’s entire corps was across the Potomac River, and Lee was hurrying Longstreet and Hill along in Ewell’s tracks.

Hooker now decided that he had to do more to counter Lee’s moves and, by ordering a series of forced marches, managed to concentrate his army between Middletown and Frederick. He still did not know where all of Lee’s army was or what Lee intended to do. For that matter, Lee had no idea that Hooker’s army had moved so far so fast; he missed Stuart’s three cavalry brigades, which if they had been present could have given him information about Hooker’s moves.

On 28 June, following a series of arguments with General Henry Halleck in Washington, Hooker resigned his command, and Major General George Meade took over, just three days before the army would become embroiled in one of the greatest battles of the 19th century.

On that day the Army of Northern Virginia was spread in a huge 70-mile semi-circle stretching from Chambersburg to Carlisle, east to the vicinity of Harrisburg, then south to York, Pennsylvania. Lee, because of Stuart’s absence and the inactivity of his other cavalry units, was moving “in the blind” and did not know in any detail where the Army of the Potomac was.

Late in the evening of the 28th, though, a “spy” rode into the Confederate headquarters and informed Lee that the Union Army was much closer than he had thought possible. The Southern commander had believed that Hooker had not yet crossed the Potomac. But the spy (a man named Harrison) said that the Federals were concentrated 25 miles South of the Pennsylvania border near Frederick, Maryland, and that Major General George Meade had relieved Hooker as commander of the Union Army. Lee knew that if this information was correct — and it was — he must either concentrate his army or subject it to possible piecemeal destruction. Accordingly, Lee ordered his corps to concentrate around Cashtown (15 miles east of Chambersburg) and a town 10 miles to the east — Gettysburg — an intersection of eight major roads.

On the morning of 29 June, Ewell’s Second Corps began moving the 25 miles from Carlisle to Gettysburg. Hill’s Third Corps moved into Cashtown, while Longstreet’s First Corps stayed in Chambersburg.

On the 30th Hill and Longstreet were in the same positions while Ewell had moved into Heidlersburg, eight miles northeast of Gettysburg. Hill’s lead division commander, Major General Henry Heth, sent one of his brigades into Gettysburg, possibly to reconnoiter the town as a concentration point. (The famous story that Heth went in to get shoes is a myth. Major General Jubal A. Early’s division had passed through Gettysburg on 26 June, and any significant provisions, including shoes, would certainly have been taken then.) Brigadier General Johnston Pettigrew, commanding this brigade, had orders not to bring on an engagement.

So late in the day — the 30th — when Pettigrew saw a body of Union cavalry approaching, he withdrew west to Cashtown to report to Heth. When he reported Union cavalry in Gettysburg, both Hill and Heth dismissed the force as nothing more than untrained state militia. Hill gave his division commander permission to move east into Gettysburg at dawn on 1 July and to brush aside the light opposition.

Meanwhile, Meade knew that Lee’s army was generally north of Gettysburg and that his own army was on an inside arc where it could protect Washington or move to meet Lee. He did not know the exact location of the Confederates. On the 28th, he had sent his troops north in two wings. Feeling that Lee’s objective was the Susquehanna River and Harrisburg, he sent his right wing units in that direction and ordered the left wing — a cavalry division and three infantry corps — under Major General John Reynolds, to threaten what appeared to be the Confederate right flank around Cashtown.

Reynolds had moved north from Frederick with the First Corps leading the way screened by a cavalry division under Brigadier General John Buford. On 30 June while Reynolds was concentrating at Emmitsburg, Maryland, Buford’s troopers had ridden ten miles farther and into Gettysburg. His scouts reported that a Confederate infantry brigade (Pettigrew’s) was withdrawing to the West.

Although Buford’s orders were simply to screen for Reynolds, he made a decision that would turn Gettysburg into a battlefield. Possibly sensing that the Confederates would be back in strength the next day (Buford had encountered some Confederates west of Gettysburg near Fairfield on the 29th), he resolved to contest that advance and asked Reynolds for infantry support. Buford then sent patrols to the west to follow Pettigrew and to the north to picket the Carlisle and Heidlersburg roads.

Early in the morning of 1 July, Meade told Reynolds to concentrate “where the enemy is strongest.” (Meade also issued his Pipe Creek circular, which outlined a plan for his army to fall back, if necessary, into northern Maryland.) With Meade’s directive and Buford’s request, Reynolds ordered the First Corps, then at Marsh Creek six miles south of Gettysburg, to march toward that town at dawn.

As the Confederate Third Corps settled down just east of Cashtown for the night, Heth told two of his brigade commanders, Brigadier Generals Joe Davis and James Archer, that they would be first in the line of march to Gettysburg on 1 July. Unknown to either of these commanders, their soldiers were on a collision course with the Union First Division (Brigadier General James Wadsworth’s) of the First Corps (Major General Abner Doubleday’s), and Buford’s two brigades of Union cavalry. This collision would produce 50,000 casualties and change the course of the Civil War.

THE TERRAIN

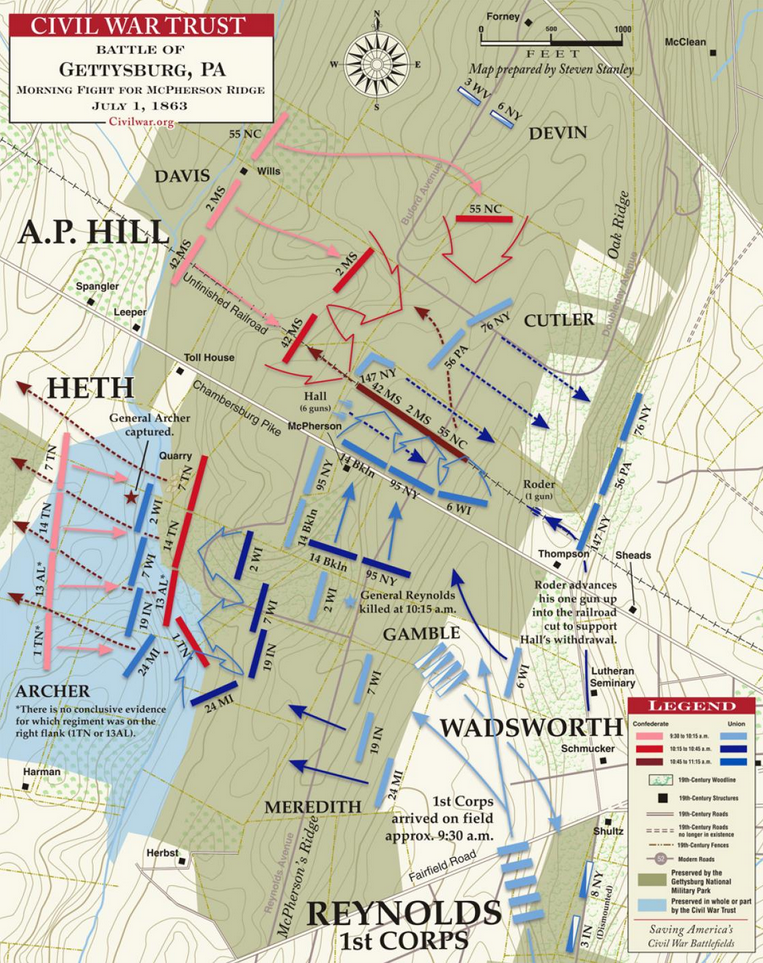

As in so many other battles, the terrain around Gettysburg and the use of it would determine the outcome of the battle to follow. At the time, the terrain west of Gettysburg consisted of a series of north-south ridges all the way to South Mountain, ten miles distant. The first of these ridges, Seminary Ridge, named for the Lutheran Seminary that was on it, was a half-mile west of the town. A quarter-mile farther west was the double-spined McPherson’s Ridge, named for the farm that was on the ridge just south of the Chambersburg Pike. Both Seminary and McPherson’s ridges ran north until they met at Oak Hill, the dominating terrain feature in the area (one mile northwest of Gettysburg).

One hundred meters south of the Pike on McPherson’s Ridge was a 17-acre grove of trees that would become a strongpoint on the first day’s fighting. Both Chambersburg Pike and Mummasburg Road cut through both ridges and ran into town. An unfinished railway grading that cut large trenches in each successive ridge ran just north of but parallel to the pike. A half-mile west of McPherson’s Ridge was yet another ridge – Herr’s Ridge; between the two ran a small stream called Willoughby’s Run.

DELAYING ACTION

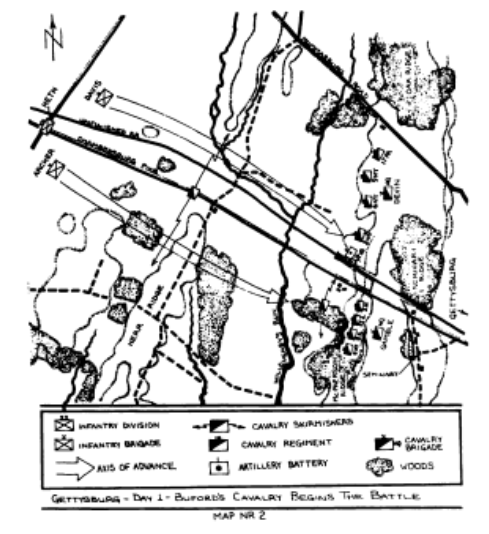

Buford believed that Hill’s Confederate corps of 20,000 men would be coming down Chambersburg Pike at dawn and that more rebels might flank him from the north. With 3,000 troopers in two brigades, he could only plan to conduct a delaying action until Reynolds arrived with infantry support.

His dispositions were perfect (see Map 2). Buford decided to actively defend to the west, so he sent only small patrols to watch the roads north of town. He arranged for four delaying positions. First, he sent a squadron (300 men) four miles to the west as pickets at the point where the Confederates would have to cross Marsh Creek. This squadron was to delay, force Heth to deploy, and report to Buford the enemy’s strengths and dispositions. Buford then placed a line of skirmishers on Herr’s Ridge, which they were to try to hold for a short time. His main line (one brigade on the left, one to the right) was on McPherson’s Ridge, and here he also placed his only battery of artillery — six three-inch rifles of Battery A, 2d U.S. Artillery. (This ridge had two spines which gave Buford’s troopers a secondary line within the main battle position.) Buford’s last ditch stand was to be made on Seminary Ridge, if need be, and he made the tower of the Seminary building his headquarters. From there he had an excellent view of the battlefield.

Despite the difference in numbers, Buford was counting on the firepower of his men (standard issue repeating carbines), on mobility, and on the depth of his positions to hold off the Confederates until help arrived. He could only hope that no Confederate force would flank him from the north.

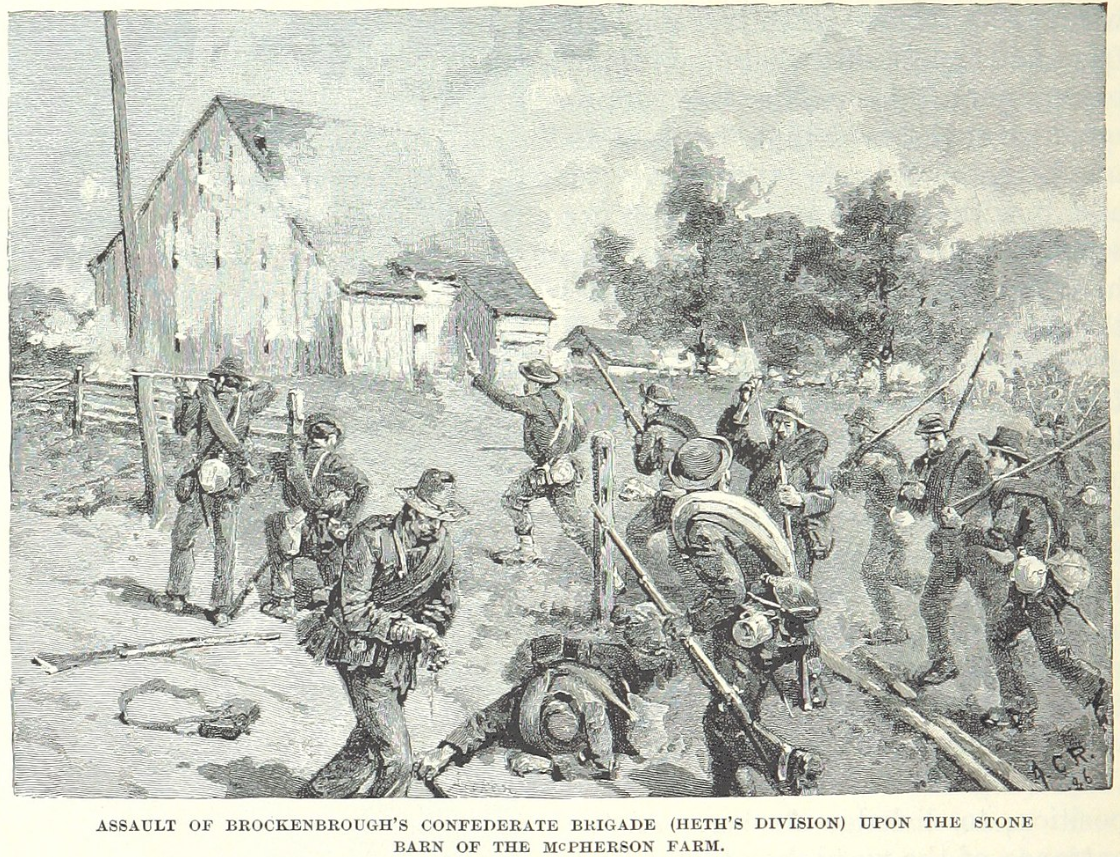

His plan could not have been executed with more precision. His forward squadron, which leapfrogged back wards using firepower and mounted mobility, delayed Heth’s forward elements until about 0800 when the Confederates, having driven off the pickets, began to assault the skirmish line on Herr’s Ridge. After a short fight, Buford withdrew his men to McPherson’s Ridge. For an hour and a half, the blue cavalrymen punished their opponents with their seven-shot repeating carbines. With Archer’s brigade on the (Confederate) right and Davis’s brigade on the left, Heth ordered an assault to drive these Union soldiers from the Ridge.

Amazing as it seems, Heth still felt his opponents were state militiamen and failed to support his two forward brigades. He did not make a reconnaissance to the left or right to determine whether he could flank this line. (Between 0800 and 1000, if he had sent one of his two remaining brigades around Buford’s left, the entire Union position would have been untenable.) Apparently, Hill was not supervising this operation closely either, because he gave Heth no specific orders.

Archer and Davis moved forward and began to drive Buford’s men off McPherson’s Ridge. At 0915 Buford must have felt he would be brushed aside because the Confederates were driving his troopers slowly back. Suddenly Reynolds appeared and told him to hang on because his leading division was only about a half-hour’s march away. Buford, therefore, ordered his men to defend the eastern-most spine of McPherson’s Ridge and to hold until relieved, which they did quite gallantly. At 1000, Wadsworth’s division moved up to relieve the cavalry just as Archer’s and Davis’s Confederates forged across McPherson’s Ridge.

Meanwhile, Buford’s patrols to the north reported a large mass of rebels moving toward Gettysburg. Buford informed Reynolds of this, then positioned his troopers to screen and protect the infantry’s left flank. As Buford’s cavalrymen fell back, Archer’s 1,200 Tennesseans and Alabamians advanced through the McPherson’s grove while Davis’s Mississippians and North Carolinians approached the eastern part of McPherson’s Ridge. Heth still was not supporting them with his two remaining brigades.

COUNTERATTACK

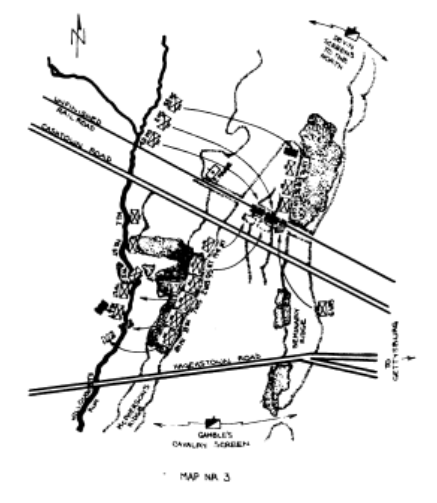

On the other side of the lines, Reynolds quickly sized up the situation. He sent Brigadier General Lysander Cutler’s brigade of New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians north of McPherson’s woods to halt Davis. The real threat, however, seemed to be Archer’s force, which Reynolds could see massing in the grove to his front. He turned to Wadsworth’s second brigade and cried, “Forward men, forward for God’s sake, and drive those fellows out of those woods!” (see Map 3.)

This brigade needed no exhorting. These were the men of Brigadier General Solomon Meredith’s legendary “Iron Brigade,” the only all-midwestern brigade in the army. With veteran silence, they moved confidently into the woods, catching Archer’s men by surprise. As the 2d and 7th Wisconsin assaulted the Confederates head-on, the 19th Indiana and the 24th Michigan formed an L-shaped line around Archer’s open right flank and delivered a devastating volley that shattered the 1st Tennessee. The Confederates, seconds before so confident, now with their flank gone and the men of the Iron Brigade assaulting them, retreated back across Willoughby Run with half their number casualties. (Archer himself was captured.) Reynolds had reacted quickly and violently and stopped Archer’s men dead in their tracks. Unfortunately, he was killed by a sniper shortly after the Iron Brigade entered the woods. Doubleday then assumed command of the Northern troops.

Meanwhile, Cutler’s brigade was in trouble at the hands of Davis. In combat for the first time, Davis had met three regiments of this Union unit and pinned them on the open ridge with his Mississippi regiments. Davis then sent his 55th North Carolina around Cutler’s open right flank. The Carolinians delivered a destructive enfilading volley that forced the three Union regiments on the right (the 56th Pennsylvania, 147th New York, and 76th New York) back to Seminary Ridge. This uncovered the remaining two regiments south of the Pike and threatened the entire First Corps position.

Davis, however, then botched what would be called today the “consolidation phase.” Instead of advancing up the ridge on line, the Confederates crowded into the unfinished railway cut for protection. Unfortunately, the sides of the cut were too steep to climb in most places. The new Union commander, Doubleday, reacted prudently. Although his defense had been breached, he skillfully counterattacked with Cutler’s two regiments south of the Pike (the 84th and 95th New York) and his corps reserve, the 6th Wisconsin of the Iron Brigade. The New Yorkers frontally assaulted the railway cut while the Wisconsin men fired straight down the cut into the left flank of Davis’s men, who eventually withdrew to the west, leaving 700 casualties behind (300 were captured in the cut). Doubleday had combined his reserve and his front line troops and massed his combat power at the crucial point in the engagement.

As Archer’s and Davis’s Confederates streamed back across Willoughby Run around 1130 and then back to Herr’s Ridge, Doubleday consolidated his positions. He placed the Iron Brigade in McPherson’s woods in a strongpoint salient with Buford protecting his left flank south of the grove. Cutler sent three regiments that had been forced to retreat back to McPherson’s Ridge north of the Pike. Meanwhile, the two remaining divisions of the First Corps were moving onto the field followed by the Eleventh Corps. Hill and Heth finally realized that this was the Army of the Potomac to their front and that it would take more than a reconnaissance in force to move it. Hill had already moved a number of artillery battalions onto Herr’s Ridge, and these loosed a furious cannonade against the Union position. The Battle of Gettysburg was on, unknown to either Lee or Meade. Even though the Confederate assault would succeed in driving the Federals back to Cemetery Hill by 1600, Buford, Reynolds, and the other Union leaders and troops had bought the Army of the Potomac some much needed time.

SUMMARY

No longer does the American infantryman depend on Springfield and Enfield rifles for his survival; no longer does the American artilleryman call for double canister to stop infantry charges. And fighting vehicles, helicopters, and tanks have taken the place of the cavalryman on the modern battlefield. But while the weapons of the present have certainly changed, basic tactics and the types of decisions combat leaders have to make remain the same. The meeting engagement at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on the morning of 1 July 1863 is much like a future first battle may be – a numerically inferior force trying to stop an aggressive foe until a stronger force can be built up to the rear. The smaller force must make the attacker pay a heavy price for the ground he gains and must get back to its main defensive line first. The first day’s battle at Gettysburg offers as good an example of a classic “meeting engagement’’ as can be found anywhere in history. Reconnaissance, cavalry screening, hasty attacks, defensive fighting, command and control, withdrawals under fire, and subordinate initiative were all present in abundance. Buford’s performance on 1 July seems to exemplify what is expected of a modern day cavalry leader, which U.S. Army FM 17-95, Cavalry, describes as follows:

Cavalry use exemplifies two essential criteria of battle. The first is the need to find the enemy and develop the situation; and the second is the need to provide reaction time and maneuver space to leave the largest possible residual of combat power in the main body for use at the time and place of decision….when fighting outnumbered, it is necessary to move to mass sufficient force to accomplish its mission . . . tight discipline and imaginative alternatives must be used to insure the cavalry commander has positive control at all times….

In future conflicts, our troops and cavalry leaders must repeat the actions of Buford’s division on a much larger scale. Our main forces will need enough reaction time. And while our reconnaissance forces may be greatly outnumbered, tight discipline and imaginative alternatives can make up for the disparity in personnel strength.

In meeting a Threat assault, the modern U.S. infantry leader must demonstrate the same expertise shown by Reynolds and Doubleday, as well as by Wadsworth, Cutler, and Meredith. In addition, our soldiers must show the same aggressiveness in the hasty attack that both Union and Confederate soldiers were noted for. As infantry leaders we must press that aggressiveness in the right direction. The Iron Brigade’s assault on Archer could have come right from the pages of FM 7-20, The Infantry Battalion:

In a hasty attack . . . the commander searches out the enemy’s weakest sector . . . concentration of effort, surprise, speed, flexibility, and audacity characterize a hasty attack perhaps more than any other operation.

The same could be said of Doubleday’s timely use of the 6th Wisconsin. Again, according to FM 7-20:

The reserve may be required to counterattack to regain critical positions or terrain. The attack is ideally launched to eliminate small penetrations when the enemy is weak and can be eſſectively isolated.

Edwin Coddington, in his definitive book, The Gettysburg Campaign, sums up not only the morning action of 1 July 1863 but the stance our present-day army must take.

The Union victory . . . may be explained by the greater tactical skill of the Northern generals . . . The rather intricate movements involved in achieving success were only possible with highly trained soldiers and quick thinking officers.

As “quick thinking officers” of the present U.S. Infantry, “Let us not,’’ as Abraham Lincoln said at Gettysburg, “forget what they did here.”

__________________________

CAPTAIN MICHAEL A. PHIPPS, a 1979 graduate of Johns Hopkins University and a student of Civil War history, recently completed the Infantry Officer Advanced Course. He has served with the 82d Airborne Division and the 3d U.S. Infantry (The Old Guard) and is now assigned to the 7th Infantry Division.

5