Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Heroes of the Indian Empire, by Ernest Foster (published 1886).

It was, however, by no ordinary man that Havelock had been thus superseded; and even if Sir James’s generous and chivalrous act, of which we shall learn more presently, had never been dreamed of, it must have been some consolation to him to feel that such a true hero had been placed over him. This distinguished soldier and statesman — born in 1803 — had served his country in various posts, in all of which he had gained high repute not only for military and administrative capacity, but especially also for splendid personal qualities. Eighteen years before this time he had distinguished himself in Cabul, when the ill-fated expedition had been despatched thither; then he had been appointed Political Agent at Goojerat, and subsequently British Resident in Sinde. It was while in the latter province that he had adopted views at variance with those of Sir Charles Napier, for he had disapproved of the policy of invading the country. But he had never allowed personal feelings to come before duty; and in spite of their disagreements, not only had Sir Charles acknowledged that Outram’s services had been of the most brilliant character, but in recognition of his courage and high sense of honour, he had bestowed on him the title of “The Bayard of India.” And, as showing Outram’s consistent conduct, when after the war in Sinde the spoils lay at the conquerors’ feet and the prize money came to be distributed, he had refused his share of it, and paid the whole amount — about £3,000 — to public charities in Bombay. Subsequently he had filled other high offices in India; and, as we have seen, he had been in command of the expedition to Persia, in which Havelock bore a part.

And what did “The Bayard of India” do when, on his return from Persia, he was appointed to take Havelock’s place as Commander of the Lucknow Relief force? Let his own words speak. Just before he reached Cawnpore, and every preparation had been made for facilitating the success of the expedition, Sir James wrote to Havelock: “I shall join you with the reinforcements. But to you shall be left the glory of relieving Lucknow, for which you have already struggled so much. I shall accompany you only in my civil capacity as Commissioner of Oude, placing my military service at your disposal, and, should you please, serving under you as a volunteer.” And on his arrival he officially announced this resolution in a Divisional Order issued to the troops.

Such was Outram’s noble conduct towards Havelock; and in the grim annals of war which this act of self-sacrifice illumines, it would be difficult to find its parallel. Nor need it be said how gratefully Havelock acknowledged Sir James’s generosity.

All preparations having been completed, the new Army of Relief — numbering rather over 3,000 men, nearly all British —- left Cawnpore on the 19th of September, and commenced the famous “march of fire” which was to complete the great deeds linked with the name of Havelock. Forward the little force pushed, and having crossed the Ganges, they came upon the rebels strongly posted at Munglewar; but a well-directed attack soon repulsed them; and then, amidst torrents of rain, the wearisome journey was resumed. Every hour was precious, for none knew how the beleaguered garrison at Lucknow might be faring by this time; so, regardless of privations and sufferings, all speed was made; and by the 23rd of the month the booming of guns around the Residency was distinctly heard, and a salute was fired by Havelock in the hope that the sound of the approach of his army might be made known to the garrison. It was on this day, too, that the troops were cheered by the news of the recapture of Delhi, which had been finally accomplished, as we have seen, a few days before. They had now reached the Alum-baugh, formerly the summer palace of the princes of Oude, some few miles from the Residency, where the foe was found to have taken up a strong position to interrupt their progress. But Havelock’s heavy guns soon cleared this obstruction, while Sir James Outram, at the head of some cavalry, bravely pursued the enemy, notwithstanding their numbers; and now, after a day devoted to much needed rest, came the final struggle — the attack on the city itself. Before this could be attempted, however, it was necessary that the sick and wounded should be cared for; it was determined, therefore, to leave them at the Alum-baugh, under a guard of 300 men—the strongest force that could be spared.

From the Alum-baugh there were three ways of reaching the Residency, and it was decided to choose the route over a bridge which crossed the canal. At the head of this bridge stood six of the enemy’s guns, while numbers of temporary fortresses with loopholed walls had also been erected to sweep the road. The order was given; and then the advance’ was made amidst a terrible stream of fire, which poured down and created sad havoc amongst the troops. But nothing could stay their progress; “there was a shout, a rush, and a brief struggle, and the battery was theirs,” after which, while the Highlanders kept the now captured bridge, the rest of the brave warriors — save those who had fallen — dashed across it. And “then Lucknow rose before them with all its gilded minarets, its rich domes, its splendid mosques, and many palaces — its regular and thickly crowded streets of houses, but all relieved by beautiful gardens, stately parks, and foliaged trees.”

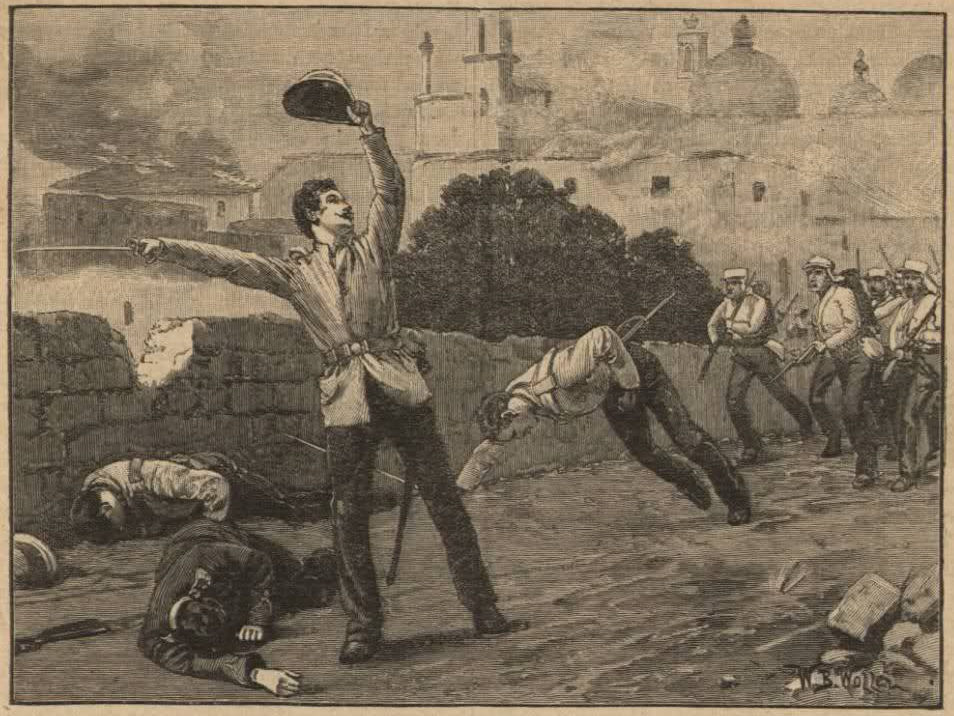

Proceeding onwards the troops ere long found themselves at the Kaiserbaugh, a fortified palace, where the whole strength of the enemy was concentrated for a final effort; but again, in face of “an iron deluge of grape, canister, and round shot,” British valour prevailed; and they were now within 500 yards of the Residency. It was nearing evening, and the troops, fighting all day, had not rested, and had scarcely tasted food; so it was thought by some that it would be wise to halt for the night. But Havelock felt there was danger in such a course, for before morning the rebels, said to be 50,000 strong, might hem in the relieving force, or even annihilate it; besides which the garrison was now believed to be in great extremity. And so the column pushed on through fire and death. Then “from every wall, from every house top, from every corner, streamed incessant storms of shot. The infuriated enemy, secure behind their walls and in their numbers, showed their heads over their parapets or from their casements, and poured forth hideous curses as they fired from their many thousand rifles on the handful below. The path was marked by the slain and the dying; the brave Neill (who had accompanied the force) fell dead; but nothing could stop our men — every obstacle was overcome; and at last the gates of the Residency appeared before the heroic remnant. It was full time. Another day, and the horrors of Cawnpore would have been repeated, for the enemy had driven their mines under the fortifications, and further resistance would have been impossible.”

The barricades of the Residency were now broken down; through the gates the deliverers fought their way; and then, says an eye-witness, “the garrison’s long pent-up feelings of anxiety and suspense burst forth in a succession of deafening cheers. From every pit, trench, and battery — from behind the sand bags piled on shattered houses — from every post still held by a, few gallant spirits — rose cheer on cheer; even from the hospital many of the wounded crawled forth to join in that glad shout of welcome to those who had so bravely come to our assistance. It was a moment never to be forgotten. The delight of the ever gallant Highlanders, who had fought twelve battles to enjoy that moment of ecstasy, and in the last four days had lost a third of their number, seemed to know no bounds…. They rushed forward, the rough-bearded warriors, and shook the ladies by the hand with loud and repeated gratulations. They took the children up in their arms and, fondly caressing them, passed them from one to another in turn. Then, when the first burst of enthusiasm was over, they mournfully turned to speak among themselves of the heavy losses they had sustained, and to inquire the names of the comrades who had fallen in the way.”

And so, with loss of over 460 killed and wounded, was Lucknow relieved, and its garrison and refugees, numbering about 1,600 in all, rescued, after a captivity of twelve weeks, from the dreadful fate which had threatened to overtake them at any moment.

On the day after entering the Residency, Havelock gave over to General Outram the chief command of the forces; and Sir James’s first thought was for the women and children, as well as for the sick and wounded, whom he hoped to convey to Cawnpore. But it was soon evident that this would not be possible; for around the captured Residency the enemy were swarming in greater numbers than ever; and the relievers were now to be themselves besieged. Nor until Sir Colin Campbell came to their rescue, six weeks later, were they able to stir out of the city.

It was just after this second relief of Lucknow had been effected that illness seized Sir Henry Havelock (who had by this time been made a Knight Commander of the Bath, while subsequently, though too late for him to be aware of it, he was created a Baronet, with a pension of £1,000 a year); and to the inexpressible grief of all it was plain that his course was nearly run. The tremendous exertions and privations of the march to Lucknow had done their work on a frame already enfeebled; and, attacked by dysentery, on the 20th of November he lay down to die.

Just before the end — which came on the morning of the 24th — he said to his comrade in arms, Sir James Outram, whose own illustrious career was to close, full of honours, within six short, years: “For more than forty years I have so ruled my life that when death came I might face it without fear.” And it was with the parting words, “Come and see how a Christian can die,” addressed to his eldest son, who had himself played a prominent part in the campaign, that this “happy warrior” fell asleep.

“Every inch a soldier, but every inch a Christian.” So had one of his chiefs, many years before, summed up Havelock’s character; and, than this, we should seek in vain for epitaph more fitting.