Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Heroes of the Indian Empire, by Ernest Foster (published 1886).

“No, I had too much else to do to be frightened; I was afraid all the pretty birds’ eggs would be smashed; so I hadn’t time to think of myself falling.”

Young Havelock, a boy of seven, climbing a tall tree in search of a nest, had tumbled from the topmost branch; and this was his reply when asked whether he was not terrified as he crashed headlong through the branches. So was it always with him. He never thought of himself; and whatever the task he took in hand he performed it regardless of his own safety.

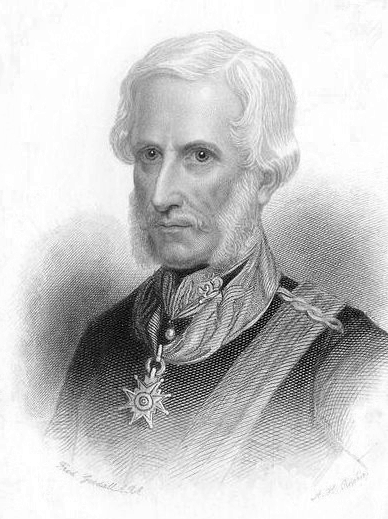

Havelock often said, in later life, that he attributed his stern notions of duty — his own ready obedience and his rigid exaction of it from others — to the discipline of the Charterhouse. And we can have no doubt that not only was such the case, but that there his whole character was formed and fixed. Born on the 5th of April, 1795, at Bishopwearmouth, near Sunderland, where his father had been a shipbuilder, Henry was sent to this famous London school (afterwards removed to Godalming) at the age of nine; and during the seven years he attended he gave every promise of a bright future. He studied hard, even gaining from his schoolmates the nickname of “Old Phloss” (a corruption of philosopher), because of his grave and thoughtful disposition; he won the love of those about him by his open-hearted, manly disposition; and he ever stood forward as champion of the weak against the strong.

It was in those days, too, that marked indications were given of the two strong characteristics by which his life was distinguished — his interest in religion, and his fondness for everything pertaining to military matters. And while on the one hand we find him with Napoleon Bonaparte as his favourite hero, eagerly reading every book he could obtain about great battles, so on the other we find the religious impressions received at his mother’s knee becoming more and more deepened. Not that he made a parade of his convictions: they were a source of happiness to him, and as such he clung to them; nor could any taunt from this or that companion deter him from putting into everyday practice that in which he truly believed.

It was his mother’s wish that young Havelock should be trained to the law, and, contrary to his own inclination, he, after leaving the Charterhouse, entered at the Middle Temple. But owing to some misunderstanding with his father, means of support were withdrawn from him; and at the end of six months he was thrown on his own resources. His brother William had just then come home from Waterloo — a circumstance which again directed Henry’s thoughts to the army; so seeking his advice and influence, he was enabled to obtain a commission as second lieutenant in the 95th Rifles.

His profession thus definitely fixed, he now gave his whole thoughts to the mastery of it. “He read,” says his brother-in-law, Mr. Marshman, “every military memoir within his reach. He laid in a rich store for his future guidance. He became familiar with every memorable battle and siege of ancient and modern times, and examined the detail and the result of every movement in the field with the eye of a soldier.” And in thus fitting himself for the work that lay before him, eight years passed — most of them spent in different parts of the United Kingdom. Then it was that in the hope of seeing active service he exchanged into an infantry regiment bound to the East; and having studied Hindostani and Persian in London, he embarked for Calcutta in January, 1823.

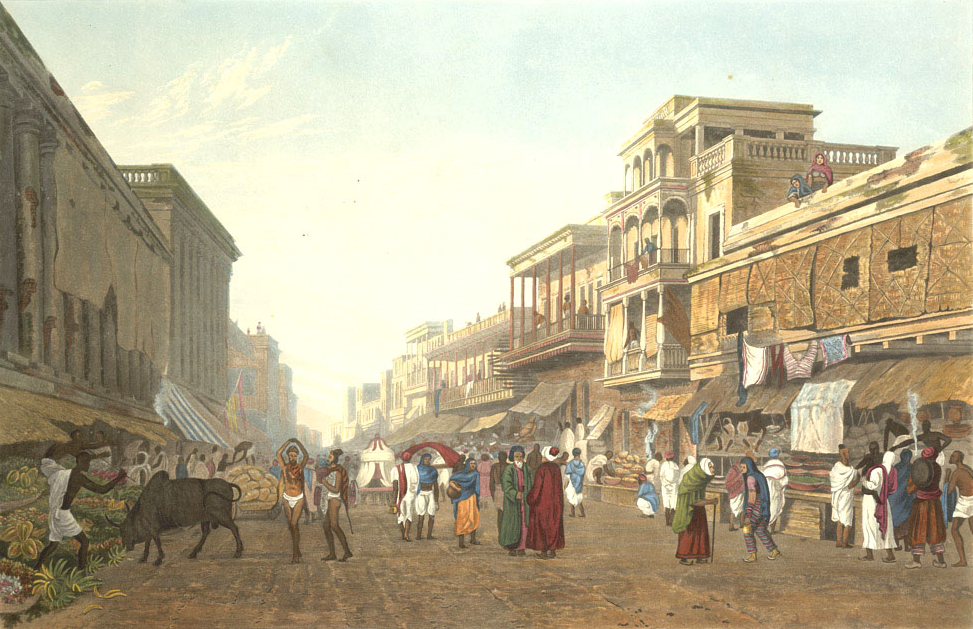

On landing in India Havelock, amid all his military duties, took practical interest in every kind of religious work. He associated himself with the missionaries at Serampore; he sought the acquaintance of ministers and others in Calcutta; and it was now that he began to devote himself to the spiritual and moral welfare of his regiment. He would assemble the men together when there was leisure, that they might hold religious converse or join together in prayer or worship; and in this way he gained over them a strong influence for good. It was no easy task — especially at first — surrounded as he was by many only too ready to scoff at his efforts; but he never faltered, and all through his life he kept up the practice of holding such services.

In the year after his arrival in India, he was serving in Burmah, where there was war; and after the capture of Rangoon, there was fear of excesses on the part of the victorious troops. Havelock was not content to go about imploring the soldiers to keep within bounds, but he was accustomed to assemble his men for worship in the grand Buddhist pagoda of the city. An officer relates that as he was wandering round this place one day, “he heard the sound of distant psalmody, and threading his way through the passages to the spot whence it proceeded, he found himself in a small side chapel with little images of Buddha arranged round the room. A little oil lamp had been placed in the lap of each figure, and the pious soldiers of the 13th were standing up, with Havelock in their midst, singing a Christian hymn.” And, as showing the practical results of his teaching, the following incident in the same campaign is recorded. One night the army was suddenly apprised of the near approach of the enemy; and a certain corps was directed to take a post of danger. But so many men of that regiment were intoxicated that they would not obey the order.

“Then call out Havelock’s saints,” exclaimed the General; “they are always sober, and can be depended upon; and Havelock himself is always ready!”

And the bugle sounded, and by these “saints” the enemy were promptly repulsed.

Nor was Havelock’s desire to do good to those around him confined to teaching and preaching. Though only a subaltern, he cheerfully sacrificed one tenth of his slender pay to objects of benevolence; and even in later years, although family claims increased, he continued to devote that proportion of his income to similar purposes.

But while he thus exhibited the religious side of his character, he gave abundant proof of splendid soldierly qualities; and his coolness, courage, and knowledge of military science won the regard and admiration of all. Some have said that he was too rigid a disciplinarian; but though he expected strictest obedience from those under him, he never exacted more than he was willing to submit to himself. No man could have recognised the claims of duty more fully than he did. A characteristic illustration of this was given on his wedding day. He had returned to India from Burmah in 1829, and he was to be married at Serampore to a daughter of Dr. Marshman, one of the Baptist missionaries there. But it happened that he was summoned to attend a court-martial in Calcutta at noon the same day. What was he to do? His friends urged him to absent himself from it, on the ground that so important an event would be considered to form sufficient excuse. But their entreaties were in vain. “He maintained that, as a soldier, he was bound to obey orders, regardless of his own convenience. The marriage was therefore solemnised at an earlier hour, after which he proceeded to Calcutta by a swift boat, attended the court, and returned to Serampore in time for the nuptial banquet.”

Havelock’s regiment — the 13th — now moved from place to place in India; but having by this time made himself proficient in Oriental languages, he left it temporarily in 1834 to become interpreter to the 16th Regiment, then stationed at Cawnpore. In the following year he rejoined the 13th, having been appointed adjutant. When he was proposed for this, some of the officers wrote to Lord William Bentinck, the Governor-General, to protest, on account of his religious habits.

“But,” said Lord William, who had found out on inquiry that Havelock’s men were the best-behaved in the regiment, “there is no reflection on his courage, or his loyalty, or his moral character?”

“Not the least; but he is a Baptist!”

“I only wish the whole regiment were Baptists, too!” was his lordship’s reply; and Havelock received the appointment.

Notwithstanding all his merits, promotion came very slowly to Havelock, while, not being a rich man, he was prevented from rising to higher rank by purchase; and he had been twenty-three years in the army before he was made captain. This rank was attained in 1838, shortly after which he was ordered to Afghanistan, to accompany the expedition to Cabul to reinstate Shah Soojah. He exhibited his wonted bravery during this campaign, being always found where the fire was fiercest and the enemy most obstinate; and when, in 1841, he took part in the prolonged defence of Jellalabad, under General Sale, it was in a large measure due to his bold measures that the besiegers were unsuccessful. Great though they were, however, for these services he was only promoted to a majority, and made a Companion of the Bath.

Next we find him acting as interpreter to Sir Hugh Gough, the Commander-in-Chief; and when the first Sikh war was raging, he had two horses shot under him at Moodkee; while at the battle of Sobraon a cannon ball entered his charger through the saddle-cloth, and passed within an inch of his thigh.

Soon after these events — like so many of the great heroes of India — Havelock found his health fail; and reluctant though he was to do so at first, he embarked for his native land in 1849, in search of rest and strength. Then after a pleasant stay of two years, first in England, afterwards at Bonn — where he left his wife and children — he returned to the East as brevet-colonel; and not long afterwards he became Quartermaster-General and Adjutant-General of the Queen’s troops in India. His duties during the next five years called him to various parts of the Empire; and it was at the end of that time that he was eagerly looking forward to being rejoined at Bombay by Mrs. Havelock and one or two of the children. But it was not to be. Just before the time arranged for the happy meeting, a sudden and unexpected call to duty came, which caused its postponement, and the brave soldier was never to see his wife again.

At the beginning of 1857 war broke out against Persia, and when, on the recommendation of Sir James Outram, Havelock was appointed to the command of a division, he accepted it. “When the post of honour and danger was offered me by telegraph,” he wrote, “old as I am, I did not hesitate a moment;” and he immediately started for Bombay, whence he sailed in the month of January. During this campaign — in which his eldest son, Henry, who had now joined him, also took part — Havelock won high praise from Sir James Outram for the skill and courage which he again displayed; and in no small degree he contributed to the success of the British operations, which came to a close within two months, when the Persians were beaten, and a treaty of peace signed. Another instance of Havelock’s courage was given during this expedition. As the steamer, conveying his men to Persia, was nearing the coast, he saw that they must be exposed to a heavy cannonade from a fort that was bristling with guns. Thereupon he ordered his men to lie down flat on the deck, and then took his own station on the paddle box, to act as emergency might require. The danger to himself, we are told, was imminent, for there came around him a perfect shower of bullets; but he escaped unhurt.

The campaign in Persia was scarcely at an end when the Mutiny broke out: and when Havelock returned to Bombay at the end of May he was greeted with the intelligence that the Sepoys had risen in revolt at Meerut, that Delhi was in possession of the insurgents, and that disaffection was everywhere spreading in the Upper Provinces. He resolved, therefore, to lose no time in placing his services at the disposal of the Commander-in-Chief; so he took passage to Galle, where he would get an early steamer to Calcutta. It was during this voyage that Havelock had a narrow escape from drowning. As the vessel neared Ceylon she struck upon a reef and became a total wreck. Every moment it was expected that she would go down head foremost; while, to make matters worse, the captain lost his nerve, and the crew became first helpless and then insubordinate. It was when the vessel struck again, and confusion grew worse confounded, that Havelock sought to reassure the sailors. “Now, my men,” cried he, “if you will but obey me, and keep from the spirit cask, we shall all be saved!” And such was the effect of his words that the affrighted crew recovered their calmness, and no lives were lost.

It was on reaching Calcutta, about the middle of June, that Havelock heard that Cawnpore was threatened, and that Lucknow was pressed hard; and he was at once appointed, with the rank of Brigadier General, to the command of the Flying Column for the relief of those places. Hastening to Allahabad, where on his arrival he heard of the surrender of General Wheeler, and of the terrible massacre that followed, he marched from there, within a few days, at the head of only 1,000 European troops, 130 loyal Sikhs, and six guns. It was with such a force, and through a country “which was one sea of mutiny,” that Havelock was expected to do his work; and after joining hands within a day or two with a small detachment, numbering a few hundreds, under Major Renaud, which had already gone forward a short distance, he arrived at Futtehpore. It had been a terrible journey, for it was now the rainy season, and, in addition to having to bear the scorching sun, the troops had been often delayed on the march, owing to the rivers being full, and the country in many places quite under water.

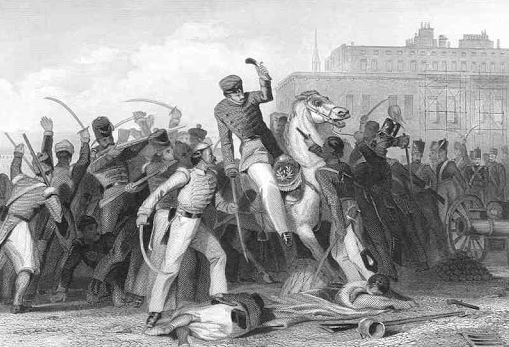

Scarcely had the column encamped at Futtehpore when spies brought in news that the enemy was advancing, some thousands strong, and at the same moment a shot fell close to the General. Every man flew to his post, and soon a heavy fire was opened; but the rebels, though there were 4,000 of them, were no match for the British, and before long they had fled, leaving behind eleven guns.

The march to Cawnpore was now resumed, and three days later another battle was fought, and the enemy utterly routed. The heat during this time was so intense that already twelve men had died from exposure to it, while the fatigue which the troops endured was indescribable.

They were now nearing their goal; but on approaching the bridge of the Pandoo River, which they would have to cross to reach Cawnpore, they found it defended by heavy guns, and the enemy entrenched on the opposite bank. Again Havelock’s men rushed forward, and eventually the enemy gave in at all points, and made for Cawnpore. The gallant little army now crossed the bridge, and on the following day stood face to face with Nana Sahib’s forces, numbering 5,000, strongly entrenched, and so sheltered that it seemed hopeless to attack them. Havelock showed no hesitation, and soon “the admirable strategy of the commander, and the indomitable courage of the British soldiers, especially the 78th Highlanders, gave him a brilliant victory.” The battle commenced at two o’clock in the afternoon, and when evening came, and darkness was approaching, Havelock saw that there was no time to be lost. Pointing to some of the enemy’s artillery, he then rode up to his Highlanders and exclaimed: “Those guns must be taken by the bayonet; and, men, remember I am with you.” And on hearing this command the brave fellows, “like a pack of greyhounds,” dashed forward with a ringing cheer; and so effectual was this movement, that without waiting for the bayonets the rebels had lost all heart, and retreated—hopelessly beaten.

It was on the next morning, July 17th, that Havelock and his army, in full belief that, after their terrible march of 126 miles, the rescue of the 200 women and children whom Nana Sahib had made prisoners was to be accomplished, entered Cawnpore. But what an awful sight met their view On hearing that Havelock had carried the Pandoo bridge, and was advancing on the town, Nana Sahib had crowned his previous atrocities by a deed even more hideous. He had seized his prisoners, butchered them in cold blood, hacked their bodies to pieces, and thrown them all into a deep well! And when Havelock and his troops entered the building in which these helpless women and children had been confined, it was not to free them, but to behold a scene never surpassed in horror. The three narrow rooms in which the captives had been kept were swimming in blood two inches deep; and lying around were scores of mournful relics — little shoes belonging to the children, portions of dresses, leaves of Bibles, locks of hair, and many others — while not far off was the ghastly well into which, some only half dead, the poor creatures had been ruthlessly cast. Well might the soldiers shed tears as they gazed on the scene; well might they, with clenched teeth, swear to avenge the awful massacre.

Too late to rescue the prisoners of Cawnpore, Havelock could now only prepare to press on to Lucknow, from which the sad news of the death of Sir Henry Lawrence had arrived; and having burned to the ground the palace at Bithoor, belonging to Nana Sahib — who had by this time fled with his army — the British marched forward on the 25th of July. Cawnpore was meanwhile left under the command of Colonel Neill, who had just come in with a small force.

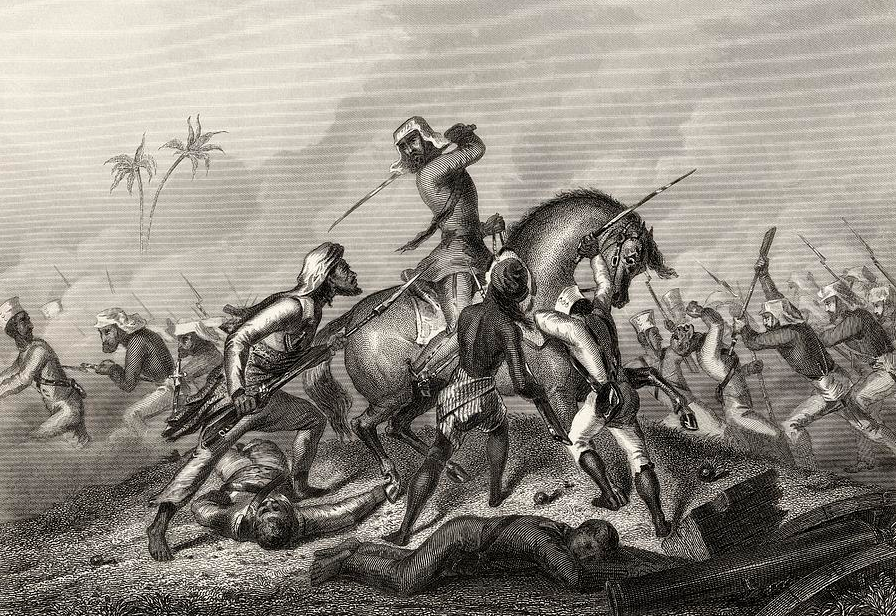

But difficulties greater than any Havelock had yet experienced now began to arise. On the 29th of July, having crossed the Ganges, he had beaten the enemy, some thousands in number, at Aong, capturing fifteen guns; and then another victory was won at Busseerut-gunge. But by this time, besides having lost eighty-eight officers and men in these actions, his troops were being decimated by sickness, and there seemed likely to be many more obstacles to their advance as they neared Lucknow — thirty-eight miles distant. So the general resolved to return to Munglewar to await reinforcements, which he had begged to be sent from Calcutta. But these did not come; and he made a second attempt to advance. Again reaching Busseerut-gunge, he defeated 20,000 mutineers with great slaughter; but the cholera then arrested his march. He therefore returned to Cawnpore. And for more than one reason it was fortunate that he thus turned back; for by this time Nana Sahib had reappeared with a large force at Bithoor, and was threatening Colonel Neill. As soon as Havelock arrived he therefore marched out to Bithoor; and at that place he defeated 4,000 of the rebels, and again put them to flight.

It was after this victory, when his men in spite of their fatigue cheered Havelock, that he said to them, “Don’t cheer me, my men; you did it all yourselves!” and it was on the morning afterwards that he issued his famous Order of the Day, in which the following passages occur: “If,” said he, “conquest can now be achieved under the most trying circumstances, what will be the triumph and retribution of the time when the armies from China, from the Cape, and from England, shall sweep through the land? Soldiers, in that moment your labours, your privations, your sufferings and your valour will not be forgotten by a grateful country. You will be acknowledged to have been the stay and prop of British India in the time of her severest trial.”

Havelock’s army, now sadly reduced by battle and disease, was doomed to enforced inactivity at Cawnpore for five weeks, by which time the reinforcements of which he stood in need arrived. But meanwhile unexpected and startling news reached Havelock. He was to be superseded! Though he had won battle after battle, surmounted the greatest difficulties by which a general could be beset, the Government of India had thought fit to deprive him of his command, and had appointed Sir James Outram in his stead. Sir James was also to resume his duties as Chief Commissioner of Oude — a post he had a few years before given up through ill-health — in succession to Sir Henry Lawrence. It was a cruel blow, and why such a step should have been taken is incomprehensible, but such was the official decision; and whether it had been arrived at thoughtlessly or otherwise, Havelock could only bow to it manfully.