Editor’s note: The following is extracted from African Nature Notes and Reminiscences, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1908). All spelling in the original.

It has always appeared to me that the qualities and characteristics of the African spotted hyæna have met with somewhat scant recognition at the hands of writers on sport, travel, and natural history, for this animal is usually tersely described as a cowardly, skulking brute, and then dismissed with a few contemptuous words.

Yet I think that the spotted hyæna of Africa is quite as dangerous and destructive an animal as the wolf of North America, which is usually treated with respect, sometimes with sympathy, by its biographers, though I cannot see that wolves are in any way nobler in character than hyænas. Both breeds roam abroad by night, ever crafty, fierce, and hungry, and both will be equally ready to tear open the graves and devour the flesh of human beings, should the opportunity present itself, whether on the shores of the Arctic Sea, where men’s skins are yellowy brown, or beneath the shadow of the Southern Cross, where they are sooty black. There is nothing really noble, though much that is interesting, in the nature of either wolves or hyænas, but neither of these animals ought to be despised. Hyænas are big, powerful, dangerous brutes, and at night often show great determination and courage in their attempts to obtain food at the expense of human beings. The following story will illustrate, I think, both the strength and the audacity of a spotted hyæna.

I was once camped many years ago near a small native village on the high veld of Mashunaland to the south-east of the present town of Salisbury. A piece of ground some fifty yards long by twenty in breadth had been enclosed by a small light hedge made of thornless boughs, as it was supposed that there were no lions in this part of the country. In the midst of this enclosure my waggon was standing one night with the oxen tied to the yokes, and my two shooting horses fastened to the wheels. On the previous day I had shot three eland bulls, and had had every scrap of the meat as well as the skins and heads carried to my waggon, and on the evening of the following day there were a large number of natives in my camp from the surrounding villages. These men had brought me an abundant supply of native beer, ground nuts, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, maize, etc., and as I, on my side, had given them several hundredweights of meat, both they and my own boys were preparing to make a night of it in my encampment.

About an hour after dark, the boy who looked after my horses stretched one of the eland hides on the ground behind the waggon, and then pouring a large pot full of half-boiled maize upon it, spread it out to cool before putting it into the horses’ nosebags for their evening feed. At this time my whole camp was lighted up by the blazing fires the natives had lit all along one side of the enclosure, and of course within the hedge. Every one was happy, with plenty of fat meat to eat and beer to drink, and the whole crowd kept up an incessant babble of talk and laughter, as only happy Africans can.

I was quite alone, as I had been for months, with these good-tempered primitive people, and I may here say that I went to sleep every night in their midst, and always completely in their power (as I had not a single armed follower with me), feeling as absolutely safe, as indeed I was, as if I had been in an hotel in London.

I had just finished my evening meal, and was sitting by the fire that had been lighted at the foot of my bed of dry grass, when I saw a big hyæna burst through the lightly made hedge of boughs on the other side of the waggon and advance boldly into the centre of the enclosure, where he stood for a moment looking about him, plainly visible to every one in the bright light cast by twenty fires. The next moment he advanced to where the eland skin lay spread upon the ground behind the waggon, and seizing it, dashed back with it through the fence and disappeared into the darkness of the night.

I had several large dogs with me on this trip, which were all lying near the fires when the hyæna entered the encampment from the other side, but as the latter had come up against the wind, they had not smelt him. When, however, he appeared within a few yards of them, and in the full light of the fires, they of course saw him, and as he seized the eland skin and dashed off with it, scattering my horses’ feed to the winds as he did so, the dogs rushed after him, barking loudly. I do not know exactly what the green hide of a big eland bull may weigh, but it is certainly very much heavier than the skin of a bullock, and of course a very awkward thing to carry off, as the weight would be distributed over so much ground. Yet, although this hyæna had only a start of a few yards, my dogs did not overtake him, or at any rate did not force him to drop the skin, until he had reached the little stream of water that ran through the valley more than a hundred yards below my camp. Here we found the dogs guarding it a few minutes later, and again dragged it back to the waggon.

I knew the hyæna would follow, so I went and sat outside the camp behind a little bush on the trail of the skin, and very soon he walked close up to me. I could only just make out a something darker than the night, but as it moved, I knew it could be nothing but the animal I was waiting for, and when it was very near me I fired and wounded it, and we killed it in the little creek below the camp. It proved to be a very large old male hyæna, which the Mashunas said had lately killed several head of cattle, besides many sheep and goats.

I cannot help thinking that this hyæna must have thrown part of the heavy hide over his shoulders as he seized it, though I cannot say that I saw him do this, but if he did not half carry it, I don’t believe he could possibly have gone off with it at the pace he did, for the dogs did not overtake him until he had nearly reached the stream, more than a hundred yards distant from my camp. I am inclined to the view that this hyæna must have half carried, half dragged this heavy hide, as I once saw one of these animals seize a goat by the back of the neck, and throwing it over its shoulders, gallop off with it. This was just outside a native kraal in Western Matabeleland near the river Gwai. I had outspanned my waggon there one evening, and having bought a large fat goat, which must have weighed fifty pounds as it stood, I fastened it by one of its forelegs to one of the front wheels of the waggon. I then had some dry grass cut, and made my bed on the ground alongside of the other front wheel, not six feet distant from where the goat was fastened.

It was a brilliant moonlight night and very cold, and I had not long turned in, and was lying wide awake, when I heard the goat give a loud “baa,” and instantly turning my head, saw a hyæna seize it by the back of the neck, break the thong with which it was tied to the waggon wheel with a jerk, and go off at a gallop with, as well as I could see, the body of the goat thrown over his shoulders. All my dogs were lying round the fires where the Kafirs were sleeping when the hyæna seized the goat, and as he had come up against the wind, had not smelt him. But when the goat “baaed” they all sprang up and dashed after the marauder, closely followed by my Kafirs. The dogs caught up to the hyæna after a short chase and made him drop the goat, which the Kafirs brought back to the waggon. It was quite alive, but as it had been badly bitten behind the ears I had it killed at once.

A hyæna once played me a particularly mean trick. I was outspanned one night towards the close of the year 1891 in Mashunaland near the Hanyani river, not many miles from the town of Salisbury. It was either the night of the full moon or within a day or two of it. At any rate, it was a gloriously bright moonlight night. I had shot a reedbuck that day, and in the evening placed its hind-quarters on a flat granite rock, close to where my cart was standing. I then made my bed on the ground close to the flat rock, and, as the moonlight was so bright, never troubled to surround my camp with any kind of fence. Pulling the blanket over my head, I soon went fast asleep. During the night I woke up, and was astonished to find that it was dark. This I soon saw was owing to a complete eclipse of the moon. When the shadow had passed, and it once more became light, I found that the choice piece of antelope meat which I had placed on the stone close behind my head was gone, and I have no doubt that it had been carried off by a hyæna during the eclipse of the moon.

Hyænas are always far bolder and more dangerous in the neighbourhood of native villages than they are in the uninhabited wilderness.

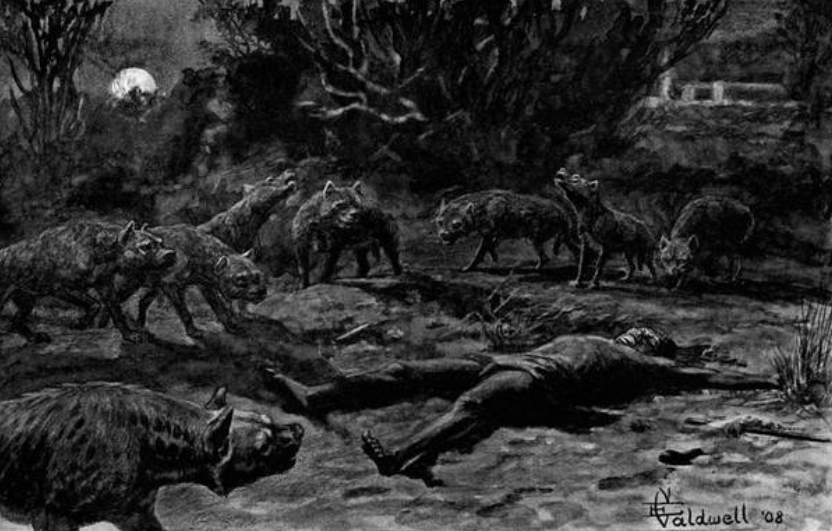

In the year 1872 a Bushman Hottentot who had shot a Kafir in cold blood, was beaten to death with clubs by friends of the murdered man close to where my waggon was standing near the Jomani river, in a wild, uninhabited part of Eastern Matabeleland. I did not know anything about this summary administration of justice until it was over, as it took place at the waggons of some Griqua hunters who were camped near me. The body of the Hottentot was then dragged to a spot less than three hundred yards from my waggon, and quite close to the Griqua encampment. That night several hyænas laughed and cackled and howled round the corpse from dark to daylight, but they never touched it. On the second night they once more left it alone, but on the third they devoured it. I do not know why these hyænas waited until the third night before making a meal off the body of this dead Hottentot, but I imagine that it was because they were hyænas of the wilderness, unaccustomed to, and therefore suspicious of the smell of a human being. I have noticed, too, that in the wilds hyænas will often, though not always, pass the carcase of a freshly killed lion without touching it.

In any part of the country, however, where there is a considerable native population, and where consequently there is little or no game, hyænas have no fear or suspicion of a dead man. They make their living out of the natives round whose villages they patrol nightly. They soon discover any weak spot in the pens where the goats, sheep, or calves are kept, and kill and carry off numbers of these animals. They often, too, kill full-grown cows by tearing their udders open and then disembowelling them, and will sometimes enter a hut, the door of which has been left open, and make a snap at the head of a sleeping man or woman, or carry off a child. When lying once very weak and ill with fever in a hut in a small Banyai village near the Zambesi, I awoke suddenly and saw a hyæna standing in the open doorway, through which the moon was shining brightly. I lay quite still and he came right inside, but he heard me moving as I caught hold of my rifle, and bolted out, carrying with him a bundle tied up with raw hide thongs. The latter he afterwards ate, but we recovered the contents of the bundle the next morning.

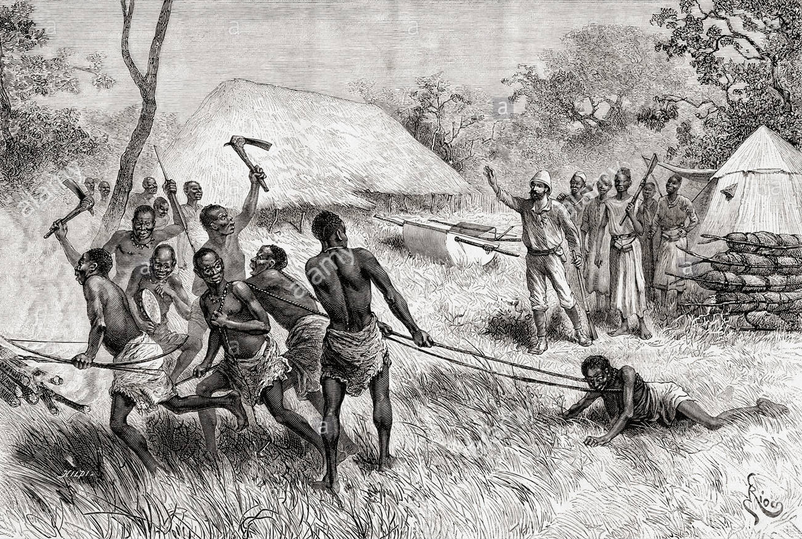

Besides being able to dig up the carelessly buried bodies of natives who have died a natural death, the customs of some of the warlike tribes used to provide hyænas with many a dainty meal. In 1873 my old friend the late Mr. Frank Mandy—afterwards for so many years the manager of De Beers Compound at Kimberley—saw some natives dragging, with thongs attached to the wrists, what he thought was a dead body across the stony ground outside the native town of Bulawayo. On going nearer he was horrified to find that the body was that of an old woman, and that she was alive. On remonstrating with the men who were dragging the poor creature along, and taxing them with their inhumanity, they seemed quite hurt, and said, “Why, what use is she? She’s an old slave, and altogether past work, and we are going to give her to the hyænas.” They accordingly dragged her down to the valley below Bulawayo and tied her to a tree. My friend had followed and watched them, and that evening, as soon as it was dusk, he and a trader named Grant—who was murdered in Mashunaland by the natives during the rising of 1896—went down to her with a stretcher, and cutting the thongs that bound her to the tree, carried her up to Mandy’s hut, where, however, she died during the night.

I do not wish it to be understood that the custom of tying old and worn-out slaves to trees, whilst still alive, to be devoured by hyænas, was very common, but it cannot have been very unusual either, as Mandy told me that many natives looked on with absolute indifference whilst the old woman whose fate I have described was dragged past them; so the hyænas must have got many a good feed in this way, especially round the larger towns. But the native custom which was most advantageous to these animals was the practice of smelling out witches. In Matabeleland, in the time of Umziligazi and his son Lo Bengula, people were continually being tried and convicted of witchcraft, and very often not only was the actual witch, man or woman, killed, but their families as well, sometimes even all their relations, as in the case of Lotchi, head Enduna of the town of Induba, who was put to death in 1888, and the number of whose wives, children, and other relations who were killed with him amounted to seventy. When the evidence had been heard the king pronounced the sentence, which was often conveyed by the two words “niga impisi” (give him, her, or them to the hyænas). The wretches were then taken just outside the kraal fence and clubbed to death. Their huts were also pulled down and thrown out. I remember I was once sleeping at the house of Mr. C——, a missionary in Matabeleland, when a lot of natives came to the door very early in the morning, and kept shouting out in a very excited manner, “Come out, missionary, and give us the witch; we want to take him to his mother, who is a witch also, and kill them both together.” It appeared that the man they said was a witch was a native, who had been left in charge of another missionary’s house during his master’s absence in the Cape Colony, and who by steady work had accumulated enough money to buy a few head of cattle. This man had been accused of bewitching some of the king’s cattle, and Lo Bengula had pronounced sentence of death upon him. Directly I saw the men outside Mr. C——’s house I thought from their manner that they had already killed the falsely accused man, although they denied having done so; but when Mr. C—— and I went across the valley towards the poor fellow’s kraal on the other side, they all left us.

It was as I had surmised; for we found Mr. H——’s faithful servant lying on his face just outside the fence of his kraal, with his elbows tied behind his back and his head in much the same condition as that of Banquo’s ghost, as represented on the London stage. On the evening of that day the sun had not been long down when we heard the hyænas howling, and that night they held high carnival over the murdered man’s remains.

Some idea of the number of hyænas that used to infest Matabeleland in the old savage times may be gathered from the fact that my old friend the late Mr. G. A. Philips once poisoned with strychnine twenty-one of these animals round the old town of Bulawayo in one night.

I was never able to get a full account of the proceedings at a trial for witchcraft in Matabeleland, but from all I have heard they must have been strangely similar to those trials for the same alleged crime which were so common a few centuries ago in England and Scotland. In recent times in Matabeleland, just as in mediæval times in England, everybody, almost without exception, believed in witchcraft, and there can be no doubt that in both countries men and women existed who firmly believed themselves to be possessed of the powers ascribed to witches. One of the commonest accusations against men accused of witchcraft in Matabeleland was that they had been seen riding a hyæna at night, and on this account when one of these animals was killed, it was looked upon as an unfeeling joke to point to it and say to any native, “Nansi ibeza yako” (“There lies your horse”).

Although hyænas eat large quantities of soft meat when they get the chance, they can do very well on a diet of little else than bones. When a large animal is killed by lions, these purely carnivorous animals eat the greater part of the soft meat, and then leave the carcase to the hyænas, which are pretty sure to be at hand. These latter then scrunch up and swallow many of the bones. So powerful are their jaws that they can break the leg-bones of buffaloes and giraffes, the ends of which they gnaw off after extracting the marrow.

I once wounded a large hyæna as he ran out of a patch of long grass, where he had been lying asleep. After following on his blood spoor for a few hundred yards, I came upon him lying under a bush, evidently badly wounded. On the previous day I had bought a very large-bladed assegai from a Mashuna blacksmith, and so, dismounting, I took this assegai from the Kafir who was carrying it, and advanced on the wounded hyæna to give him the coup de grace. When I was still about ten yards away from him, he jumped up and came towards me, not with a rush certainly, but still pretty quickly, and with the evident intent to do grievous bodily harm. As he advanced he repeatedly clacked his jaws together, making a loud noise. I stood my ground with my heavy assegai poised to strike, and when the hyæna was close to me I drove it with all my force into his mouth. His jaws closed instantly on the heavy iron blade, nor was I able to again withdraw it, for although the wounded animal bit it all over from one end to the other, he opened and shut his jaws with such surprising quickness that he never lost possession of it. Finally, he pulled the iron blade of the assegai out of its wooden shaft, and then, weakening from loss of blood, fell to the ground, still clashing his jaws on it. He was not able to rise to his feet again, and the Kafirs speared him to death as he lay. I found that the heavy assegai blade had been twisted and bent and bitten in a most extraordinary manner. I kept it for a long time, and wish I still had it in my possession, as it was a veritable curiosity.

I once caught a hyæna in a very large heavy iron trap, which it required the strength of two ordinary men to set. To this trap I had attached a heavy iron waggon chain, but the other end of this chain was not made fast to anything. I caught this hyæna by hanging up the hind-leg of a sable antelope in a tree by the roadside about a hundred yards from where my waggon was outspanned. The trap was set at the foot of the tree without any bait and carefully covered. The hyæna must have jumped up at the meat and sprung the trap as he came to the ground again. One of the large iron spikes which projected from the jaws of the trap must have gone right through the leg that had been caught, as it was broken off and there was a lot of blood on the trap. When the hyæna was caught he made no noise, at least no one heard anything, but just dragged the trap with the heavy chain attached for a distance of about a hundred yards away from the waggon road and then broke it up. One jaw of the trap had been wrenched off, and the solid iron tongue which supports the plate when such a trap is set, had been twisted right round. The trap, which would probably have held a lion, was of course destroyed and the hyæna gone.

I have killed many hyænas both near native villages and in wild uninhabited parts of the country by setting guns for them, usually baited with a lump of meat tied over the muzzle, and attached with a string to a lever rigged on to the trigger, so that a straight pull exploded the charge. Of course, one arranged the trap in such a way, with the help of a few thorn bushes, that the hyæna was obliged to take the meat from in front; but I never knew these animals show any hesitation in doing so, with the result that they received the charge full in the mouth and were killed instantly. I have no doubt, however, that if a constant practice were made of setting guns for hyænas in a certain district, they would become wary and suspicious after a few of their number had been killed.

On one occasion my own dogs held a large old bitch hyæna until the Kafirs came up and speared her, but this animal had, we afterwards discovered, been shot some time previously through the lower jaw, the end of which, with both the lower canine teeth, was gone, so that she could not bite. This hyæna was, however, very fat, and the wound she had received had long since healed up after all the broken pieces of bone had sloughed out. How she had managed to eat anything but soft food I cannot imagine, for what was left of her lower jaw, being in two separate pieces, must have been useless for scrunching up bones.

One moonlight night I wounded a large male hyæna, partially paralysing his hind-quarters, and my pack of dogs at once ran up to and attacked him. Several of these dogs were large, powerful animals, and holding the hyæna by the ears, throat, and neck, they certainly prevented him from using his teeth to their discomfort, but they seemed quite unable to pull him to the ground, and when I at last drove them off, I could not see that they had hurt him in any way, so I shot him.

My friend Mr. Percy Reid once, when hunting on the Chobi river, heard a great noise, a mixture of howls and yells going on near his camp during the night, and his Kafirs asserted that they could distinguish the cries both of wild dogs and spotted hyænas. The next morning the weird sounds were again heard, and appeared to be approaching the camp, so Mr. Reid went out to see what was going on. He had only walked a short distance when he saw a very interesting sight. An old hyæna was standing with its back to a large tree, surrounded by a double circle of some twelve to fifteen wild dogs. The inner circle of these, by turn, flew in on the hyæna and tried to bite him, falling back after they had done so, and fearing apparently to come to close quarters. At the end of some five or ten minutes the old hyæna, seizing an opportunity, bolted for an adjacent tree, and, standing with his back to this, again renewed the fight. Both the hyæna and his assailants were so intent on their own concerns that they paid no heed whatever to my friend’s approach, and he walked up to within fifty yards of them and shot two of the wild dogs. The remainder of the pack then ran off, leaving the hyæna alone. Mr. Reid would not shoot him, because of the brave and determined fight he had made, and he presently lumbered off at a heavy gallop, apparently none the worse for his all-night encounter with the wild dogs.

Hyænas do not always lie up during the day in caves or in holes in the ground. I have often found them sleeping in patches of long grass, and have had many a good gallop after them. I always found they ran very fast, though I have galloped right up to several in good open ground, but it was just as much as my horse could do to overtake them. Once whilst riding across the Mababi plain in 1879, about two hours after sunrise I heard some hyænas howling; but they were so far off that I could not see them, though the plain was perfectly level and open, as all the long summer grass had been burnt off. As the noise they were making, however, was very great and quite unaccountable by broad daylight, I determined to see what was going on, and galloped in the direction of the strange sounds. After a time I sighted a regular pack of hyænas trotting along towards the belt of thorn bush at the top end of the plain, and beyond the hyænas I could see there were three animals which looked larger and of a different build, and which I thought must be lions. I then galloped as hard as I could in order to get up to these three animals before they entered the bush. As I galloped, I passed and counted fifteen hyænas, trotting along like great dogs, most of which stopped and stood looking at me without any sign of fear as I rode close past them. All the time some of them kept howling. I now saw that the three larger animals were lionesses, and that there were several more hyænas in front of them, so that there must have been more than twenty of these animals out on the plain with the lionesses, two of which latter I succeeded in shooting. After I had skinned them, I rode back over the plain, but could discover no sign of the carcase of a dead animal, as I should have done, had it been anywhere near, by the flight of the vultures. Why had all these hyænas collected round these three lionesses, and why were they escorting them back to the bush again over the open plain? I can only hazard the suggestion that they had followed the lionesses in the hope that they would kill some large animal, whose bones they would then have picked after the nobler animals had eaten their full. When I heard them howling, perhaps they were upbraiding the lionesses for their want of success. Hyænas do not live in packs, but when a large animal has been killed, they scent the blood from afar and collect together for the feast, separating and going off singly to their several lairs soon after daybreak. The rapidity with which hyænas sometimes collect round a carcase is truly astonishing, and shows how numerous these animals are in countries where game is still plentiful.

I remember arriving late one evening, in July 1873, at a small water-hole in the country to the west of the river Gwai, in Matabeleland. I had left my waggon at a permanent water called Linquasi two days previously, but being only armed with two four-bore muzzle-loading elephant guns, and not having met with either elephants, rhinoceroses, or buffaloes, was still without meat for myself and my Kafirs, as, although I had seen giraffes, elands, and other antelopes, I had not been able to get within shot of any of these animals with the archaic weapons which were the only firearms at that time in my possession.

The water-hole was situated on the edge of a large open pan, at the back of a small hollow half beneath a low ledge of rock, and must have been fed from an underground spring, as the Bushmen told me that it never dried up.

As, on the evening in question, the moon was almost at the full, I determined to watch the water during the early hours of the night, in the hope of getting a shot at some animal at close quarters as it came to drink, for there was a great deal of recent spoor in the pan of rhinoceroses, buffaloes, zebras, and antelopes.

As soon, therefore, as my Kafirs had made a “scherm”[1] amongst some mopani trees, just beyond the edge of the open ground, I took one of my blankets and both my heavy elephant guns, and established myself on the ledge just above the pool of water. Lying flat on my stomach, I was completely hidden from the view of any animal coming towards me across the open pan by the long coarse grass, which grew right up to the edge of the rock ledge beneath which lay the pool of water.

I had not long taken up my position when a small herd of buffaloes came feeding up the valley behind me. They, however, got my wind when still some distance away from the water, and ran off.

About half an hour later, I suddenly saw a rhinoceros coming towards me across the open pan, and as the wind was now right, I thought he would be sure to come to the water.

He was, however, very suspicious, and kept continually stopping and turning sideways, apparently listening. In the brilliant moonlight I had made him out to be a black rhinoceros almost as soon as I saw him, for he held his head well up, whilst as a white rhinoceros walks along its great square muzzle almost touches the ground. At last the great beast seemed to make up its mind that no danger threatened it, for after having stood quite still for some little time about fifty yards away from me, it came on without any further hesitation and commenced to drink at the pool beneath the ledge on which I was lying. Its head was then hidden from me, but if I had held my old gun at arm’s length I could have touched it on the shoulder. Raising myself on my elbows, I now lost no time in firing into the unsuspecting animal, the muzzle of my gun almost touching it at the junction of the neck and the chest as I pulled the trigger.

The loud report of my heavily charged elephant gun was answered by the puffing snorts of the rhinoceros, which, although mortally wounded, had strength enough to swing round and run about fifty yards across the open ground before falling dead.

As it was still quite early, and the night was so gloriously fine, I thought I would lie and watch for an hour or two longer to see if anything else came to drink at the water.

I don’t think the rhinoceros had been dead five minutes when a hyæna came across the pan and went straight up to the carcase. This first arrival was soon followed by others, and in less than half an hour there were at least a dozen of these ravenous creatures assembled for the prospective feast. All the time I was watching them they neither howled nor laughed nor fought amongst themselves, but kept continually walking round the dead rhinoceros, or watching whilst one or other of their number attempted to tear the carcase open. This they always attempted to do at the same place—in the flank just where the thigh joins the belly. The soft, thick, spongy skin, however, resisted all their efforts as long as I left them undisturbed, though I could hear their teeth grating over its rough surface. Presently I heard a troop of lions roaring in the distance, and as I thought they might be coming to drink at the pool of water close to which I was lying all by myself and without any kind of shelter, I stood up and shouted to my Kafirs to come and cut up the rhinoceros, and bring some dry wood with them so that we could make a fire near the carcase.

As my hungry boys came running up, the hyænas hastily retired; but after we had opened the carcase of the rhinoceros and cut out the heart and liver and some of the choicest pieces of meat and carried them to our camp, they returned and feasted on what was left to their heart’s content. The noise they made during the remainder of the night, howling, laughing, and cackling, was in strange contrast to their silence when they first came to the carcase, but found themselves unable to get at the meat, owing to the thickness of the hide by which it was covered. The lions which I had heard roaring in the distance did not come to drink at the pool near which we were encamped. They were probably on their way to a much larger pool of water some miles to the eastward.

Spotted hyænas are very noisy animals, and their eerie, mournful howling is the commonest sound to break the silence of an African night.

The ordinary howl of the spotted hyæna commences with a long-drawn-out, mournful moan, rising in cadence till it ends in a shriek, altogether one of the weirdest sounds in nature. It is only rarely that one hears hyænas laugh in the wilds of Africa, as these animals can be made to do in the Zoological Gardens by tantalising them with a piece of meat held just beyond their reach outside the bars of their cage. But when a lot of hyænas have gathered together round the carcase of a large animal, such as an elephant or a rhinoceros, and are feasting on it undisturbed, the noises they make are most interesting to listen to. They laugh, they shriek, they howl, and in addition they make all kinds of gurgling, grunting, cackling noises, impossible to describe accurately. Once, late one evening in 1873, I shot a white rhinoceros cow that had a smallish calf, which, however, I thought was large enough to fend for itself and get its own living. That night, after having cut off all the best and fattest meat of the rhinoceros, we camped some two hundred yards from the carcase, which lay in an open valley close to a pool of water. Soon after dark the hyænas began to collect for the feast, and whether the calf returned to its mother’s remains and the hyænas forthwith attacked it, or whether it resented their presence and first attacked them, I do not know; but we first heard it snorting and then squealing like a pig, and for half the night it was rushing about, closely pursued by some of the hyænas, which, I fancy, must have been hanging on to its ears and any other part they could get hold of. Twice the young rhinoceros charged almost into our camp, squealing lustily. Finally, the hyænas killed it, and had left hardly anything of it the next morning. I shall never forget the extraordinary noises these animals made that night.

Contrary to generally accepted ideas, I have not found hyænas when killed to be more stinking animals than other carnivorous beasts. The carcase of a freshly killed hyæna certainly does not smell as strongly as that of a lion. I have often had the raw hide neck straps attached to the ox yokes of my South African waggon eaten by hyænas at night in Matabeleland, and to do this, these animals must have been right amongst the oxen, gnawing the raw hide thongs within a few feet of them, yet I never remember such a proceeding to have caused them any alarm. On three occasions, two of which were on bright moonlight nights, I actually saw hyænas right in amongst my oxen, and at first thought they were dogs, as they were sniffing about on the ground. Two of these hyænas I shot. On all these occasions my oxen did not pay the very slightest attention to the hyænas, and I cannot therefore believe that these animals have a more fetid or disagreeable smell than dogs. I remember once shooting a hyæna in the Mababi country, close to the permanent camp where my waggons stood all through the dry season of 1879. Several waggons belonging to Khama’s people were standing close by, and when Tinkarn, the headman of the party, saw the dead hyæna he asked me if he and his people might have it. When I inquired what they wanted it for, they answered “To eat,” and averred that no other meat obtainable in the African veld was equal to that of a fat hyæna. I gave them the coveted carcase, and they ate it with every appearance of satisfaction. These men were not low savages, but Christianised Bechwanas, all of whom could read and write. They had plenty of good antelope meat, too, at the time, so that they certainly ate the hyæna from choice. I have, however, never come across any other tribe of African natives who would willingly eat the flesh of a hyæna, their objection to it being that it is that of an animal which eats the bodies of human beings. This objection, however, would not apply to the vast majority of hyænas that live in the wilderness, far from any human habitations. Hyænas will attack and kill old and worn-out oxen after they have become very weak; but I have never heard of a case of an ox or a horse in good condition being interfered with by these animals. They often kill the small native cows of South-East Africa, however, always tearing open their udders, and then dragging out their entrails through the wound thus made. I once started on a journey down the northern bank of the central Zambesi in 1877, taking with me four fine strong donkeys. Three of these donkeys were killed near the mouth of the Kafukwe river by hyænas, and the fourth badly lacerated. These donkeys were so completely devoured by what, judging from the noise they made, must have been a regular pack of hyænas, that it was impossible to tell how they had been killed. In 1882, when travelling through the eastern part of Mashunaland beyond the Hanyani river, I had a very fine large stallion donkey killed one night close to my camp by a single hyæna. We heard the poor creature give a heart-rending screaming cry when it was first seized, and ran to its assistance at once, but when we got to it, it was already dead. Its powerful, strong-jawed assailant had seized it between the hind-legs, torn a great hole in its abdomen, and dragged out half its entrails in an incredibly short space of time.

I have never measured or weighed any of the hyænas I have shot, but Mr. Vaughan Kirby speaks of a very large one as having stood three feet high at the shoulder, and I believe that such an animal must have weighed more than 200 pounds.

Very little is known of the life-history of the spotted hyæna. Bushmen have told me that the females give birth only to two whelps at a time. These are usually born in one of the large holes excavated by the African ant-eaters (Aardvarks). Although I have seen a great number of hyænas on various moonlight nights, I have never seen a very young or even a half-grown one accompanying its mother, and I cannot help thinking, therefore, that young spotted hyænas remain in the burrows where they are born, and are there fed by their parents until they are at least eight or nine months old.

______________________

[1] A semicircular hedge of thorn bushes within which we slept with fires at our feet.

5