Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Thanksgiving: Its Origin, Celebration and Significance as Related in Prose and Verse, by Robert Haven Schauffler (published 1907).

While Thanksgiving in its present form is a distinctively American holiday, it did not spring Minerva-like from the brain of Governor Bradford in 1621 as some imagine. On the contrary we may trace its origin back through the ages and the nations to the land of the Canaanites from whom the Children of Israel copied many of their customs. In the book of Judges we read of the Canaanites:

“And they went out into the field, and gathered their vineyards, and trode the grapes and held festival, and went into the house of their god, and did eat and drink.”

This vintage or harvest celebration appeared later among the Hebrews, as an act of worship to Jehovah and was called The Feast of Tabernacles because everyone lived in booths or tents during the festival in memory of the years when the nation had had no settled home.

In Deuteronomy, Moses transmitted these directions about the holiday:

“Thou shalt keep the feast of tabernacles seven days, after that thou hast gathered in from thy threshing-floor and from thy winepress; and thou shalt rejoice in thy feast, thou, and thy son, and thy daughter, and thy manservant and thy maidservant, and the Levite, and the stranger, and the fatherless, and the widow, that are within thy gates. Seven days shalt thou keep a feast unto the Lord thy God…. because the Lord thy God shall bless thee in all thine increase, and in all the work of thine hands, and thou shalt be altogether joyful.”

In Leviticus the command is, “When ye have gathered in the fruit of the land, ye shall keep a feast unto the Lord….and ye shall rejoice before the Lord your God seven days.”

Nothing could be more fitting and spontaneous than these thanksgivings after harvest which constituted the principal festival of the Jewish year. In the book of Nehemiah the Lord commanded, “Go forth unto the mount, and fetch olive branches, and branches of wild olive, and myrtle branches, and palm branches, and branches of thick trees, to make booths…. So the people went forth and brought them, and made themselves booths, every one upon the roof of his house, and in their courts, and in the courts of the house of God, and in the broad place of the water gate…. And there was very great gladness.”

The harvest festival of ancient Greece, called the Thesmophoria was akin to the Jewish Feast of Tabernacles. It was the feast of Demeter, the foundress of agriculture and goddess of harvests, and was celebrated in Athens, in November, by married women only. Two wealthy and distinguished ladies were chosen to perform the sacred function in the name of the others and to prepare the sacred meal, which corresponded to our Thanksgiving dinner. On the first day of the feast, amid great mirth and rejoicing, the women went in procession to the promontory of Colias and celebrated their Thanksgiving for three days in the temple of Demeter. On their return a festival occurred for three days in Athens, sad at first but gradually growing into an orgy of mirth and dancing. Here a cow and a sow were offered to Demeter, besides fruit and honeycombs. The symbols of the fruitful goddess were poppies and ears of corn, a basket of fruit and a little pig.

The Romans worshipped this harvest deity under the name of Ceres. Her festival, which occurred yearly on October 4th, was called the Cerelia. It began with a fast among the common people who offered her a sow and the first cuttings of the harvest. There were processions in the fields with music and rustic sports and the ceremonies ended with the inevitable feast of thanksgiving.

In England the autumnal festival was called the Harvest Home, which may be traced back to the Saxons of the time of Egbert. “It was known in Scotland as the Kern,” writes Walsh in his Curiosities of Popular Customs, “and was a peculiarly secular method of celebrating the close of the harvest. This still has its local survivals, although they are fast passing away before the modern innovation of a general harvest festival for the whole parish, to which all the farmers are expected to contribute, and which their laborers may freely attend. This festival is commenced with a special service in the village church, beautifully decorated for the occasion with fruit and flowers, followed by a dinner in a tent or in some building sufficiently large and continued with rural sports, and sometimes includes a tea-drinking for the women.

“Nevertheless, as Canon Atkinson says, we cannot even yet use the past tense in speaking of the old harvest-home. In the northern part of Northumberland,’ writes Henderson in his Folk-Lore of North England, ‘the festival takes place at the close of the reaping, not the ingathering. When the sickle is laid down and the last sheaf of corn set on end, it is said that they have “got the kern.” The reapers announce the fact by loud shouting, and an image crowned with wheat-ears and dressed in a white frock and colored ribbons is hoisted on a pole by the tallest and strongest men of the party. All circle round this “kern-baby” or harvest-queen and proceed to the barn, where they set the image on high, and proceed to do justice to the harvest-supper.’ In some places this nodding sheaf, the symbol of the god,’ is quite small, fashioned with much care and neatness, and plaited with wonderful skill; in others it is large and cumbersome, taking a strong man’s strength to bear it….

“The manner of escorting the last load to the barn varied in different places. In many parts of England it was borne in a wagon known as the hock-cart. A pipe and tabor went merrily sounding in front, and the reapers, male and female, tripped around in a hand-in-hand ring, shouting and singing. Herrick’s description shows how ancient is this custom:

Come forth, my Lord, to see the cart

Drest up with all the country art.

The horses, mares and frisking fillies

Clad all in linen white as lilies.

The harvest swains and wenches bound

For joy, to see the hock-cart crown’d.

About the cart heare how the rout

Of rural younglings raise the shout;

Pressing before, some coming after,

Those with a shout, and these with laughter.

Some blesse the cart; some kisse the sheaves;

Some prank them up with oaken leaves:

Some crosse the fill-horse; some with great

Devotion stroak the home-borne wheat;

While other rusticks, lesse attent

To prayers than to merryment,

Run after with their breeches rent.

In some provinces it was a favorite practical joke to lay an ambuscade along the road, and from the vantage-point of some tree or hill to drench the hock-party with water.

An old song with many variants still survives at the bearing home of the last load. Its usual form runs as follows:

Harvest home! harvest home!

We’ve ploughed, we’ve sowed,

We’ve reaped, we’ve mowed,

We’ve brought home every load.

Hip, hip, hip, harvest-home!

“In Herefordshire a final handful of grain was left uncut. But it was tied up and erected under the name of a mare, and the reapers then, one after another, threw their sickles at it, to cut it down. The successful individual called out, I have her!’ ‘What have you?’ cried the rest. ‘A mare, a mare, a mare!’ he replied. ‘What will you do with her?’ was then asked. ‘We’ll send her to John Snooks,’ or whatever other name, referring to some neighboring farmer who had not yet got all his grain cut down.

“This piece of rustic pleasantry was called ‘Crying the Mare.’ It evidently refers to the time when, our country lying all open in common fields, and the corn consequently exposed to the depredations of the wild mares, the season at which it was secured from their ravages was a time of rejoicing, and of exulting over a tardier neighbor.

“Clarke in his Travels (1812) gives this account of a harvest-home festival in Cambridge:

“‘At the Hawkie, as it is called, or HarvestHome, I have seen a clown dressed in woman’s clothes, having his face painted, his head decorated with ears of corn, and bearing about with him other emblems of Ceres, carried in a wagon, with great pomp and loud shouts, through the streets, the horses being covered with white sheets; and, when I inquired the meaning of the ceremony, was answered by the people that ‘they were drawing the Harvest Queen.'”

In addition to this fixed autumnal festival, extraordinary feasts were proclaimed in England upon special occasions such as the defeat of the Spanish Armada, the discovery of Guy Fawkes’s “gunpowder plot” and the recovery of George III from his fit of insanity. In fact these days of thanksgiving soon grew so numerous and so hilarious as to interfere with the more serious affairs of life, and Edward VI finally decreed it “lawful to every husbandman to labor on those holy days that come in time of harvest.”

Even during the Commonwealth under Cromwell more than one hundred feast days were observed in the course of the year and Latimer complained that when he went to preach in a certain church on a holy day he found the village deserted, the church locked, and the people all gone a-maying. These customs shocked the austere souls of the Puritans, but when they fled to Holland they grew used to the more respectable and religious fast and feast days of the Dutch.

And so, being in the blood of America’s first settlers, the custom reappeared early in our land. In the records of the expedition under Frobisher, which settled the first English colony in America, there is this entry:

“On Monday morning, May twenty-seventh, 1578, aboard the Ayde, we received all, the communion by the minister of Gravesend, prepared as good Christians toward God, and resolute men for all fortunes; and toward night we departed toward Tilbury Hope. Here we highly prayed God, and altogether, upon our knees, gave him due humble and hearty thanks, and Maister Wolfall made unto us a goodbye sermon, exhorting all especially to be thankful to God for his strange and marvelous deliverance in those dangerous places.”

This is but a specimen of the many services of thanksgiving held during the perilous pioneer days.

But the first authentic harvest festival was held by the Pilgrims in 1621. During the winter the little colony had been sorely tried. Only fifty-five of the one hundred and one settlers remained alive. They had suffered cold, hunger and disease, and, as one of them confesses, they had been terrified by the roar of “lyons.” Wolves had “sat on their tayles and grinned” at them, while the Indians had proved still more formidable.

“The spring of 1621 opened,” writes Love,[1] and the seed was sown in the fields. They watched it with anxiety, for well they knew that their lives depended on that harvest. So the days flew by and the autumn came. Never in Holland nor in Old England had they seen the like. For the most part they had worked at trades during their exile; they were now farmers, as their ancestors had been. Bounteous Nature, with the pride of a milliner at a fall opening, spread all her treasures before them. Their little plats had been blessed by the sunshine and the showers, and round about them were many evidences of the friendliness of the untilled soil. The woodland, what a revelation it must have been to them, arrayed in its autumnal garments, and swarming with game which had been concealed from them during the summer! The Pilgrim from over sea fell in love then and there with New England, and the bride, clad in her cloth of gold, had been waiting many years for such a suitor. So it happened that there was a wedding feast.”

In Mourt’s Relation is the following account of America’s first harvest festival of thanksgiving: “Our harvest being gotten in, our Governour sent foure men on fowling, that so we might after a more speciall manner rejoyce together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labours; they foure in one day killed as much fowle, as with a little help beside, served the company almost a weeke, at which time amongst other recreations, we exercised our Armes, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest King Massasoyt, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five Deere, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governour, and upon the Captaine (Standish) and others. And although it be not always so plentifull, as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodnesse of God, we are so farre from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plentie.”

Thus the first thanksgiving festival was celebrated in America and by little and little the custom spread, and its influence deepened until it has become a national holiday, proclaimed by the President, reproclaimed by the Governor of each State, and observed on the third Thursday in November by every good American and true.

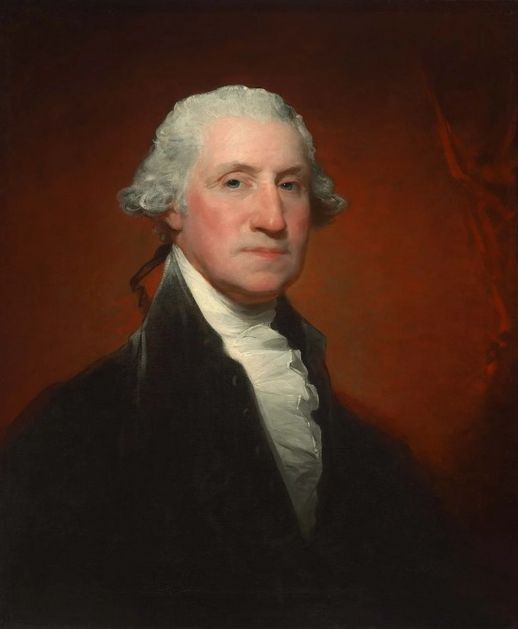

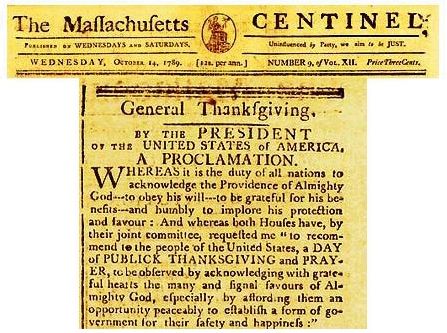

Perhaps the spirit of the festival has never been more happily expressed than by George Washington in his Thanksgiving Proclamation of 1789.

“Whereas it is the duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly to implore his protection and favor; and whereas both Houses of Congress have, by their joint Committee, requested me to recommend to the people of the United States a day of Public Thanksgiving and Prayer, to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness;”

“Now therefore, I do recommend and assign Thursday, the twenty-sixth day of November next, to be devoted by the people of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the Beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be; that we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks for his kind care and protection of the people of this country, previous to their becoming a nation; for the signal and manifold mercies, and the favorable interpositions of his providence, in the course and conclusion of the late war; for the great degree of tranquility, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed; for the peaceable and rational manner in which we have been enabled to establish Constitutions of Government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national one now lately instituted; for the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed, and the means we have of acquiring and diffusing useful knowledge; and, in general, for all the great and various favors, which He has been pleased to confer upon us.”

“And, also, that we may then unite in most humbly offering our prayers and supplications to the great Lord and Ruler of Nations, and beseech him to pardon our national and other transgressions; to enable us all, whether in public or private stations, to perform our several and relative duties properly and punctually; to render our National Government a blessing to all the people, by constantly being a government of wise, just, and constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed; to protect and guide all sovereigns and nations (especially such as have shown kindness to us,) and to bless them with good governments, peace and concord; to promote the knowledge and practice of true religion and virtue, and the increase of science, among them and us; and, generally, to grant unto all mankind such a degree of temporal prosperity as he alone knows to be best.”

(1879-1964)

_______________________________

[1] The Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England, by W. De Loss Love.

Do you take article submissions?

No.

Certificate expired…..

Gentlemen, do you intend to post anything in the future? Unless my browser is in error, there is nothing from Thanksgiving last year until now. I’ve enjoyed your articles, so it would be a shame if this resource went away.

Hey buddy, good to see you. We started out with lots of writers contributing, but that number keep dwindling until it was a couple of us running around trying to find folks that would let us cross post. We decided that was dumb. So we have kept the site up, as there is quite a bit of good material for those who are looking. Occasionally, someone will email and share something to post, or send us a link. I do think we have a couple of articles that are in the works, but for the time being, it won’t be like the old days with multiple posts every day.

That makes sense, sadly. I’m glad to see that you guys are going to keep the site up, as it is a useful resource. I’ll be back to check on things from time to time. Take care.

I appreciate you guys keeping the site up. Keep fighting the good fight.