Editor’s note: Here follow Chapters 33 through 39 of My Reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, by General Ben Viljoen (published 1902). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XXXIII

IN A TIGHT CORNER.

It was now March, 1901. For some time our burghers had been complaining of inactivity, and the weary and monotonous existence was gradually beginning to pall on them. But it became evident that April would be an eventful month, as the enemy had determined not to suffer our presence in these parts any longer. A huge movement, therefore, was being set on foot to surround us and capture the whole commando en bloc.

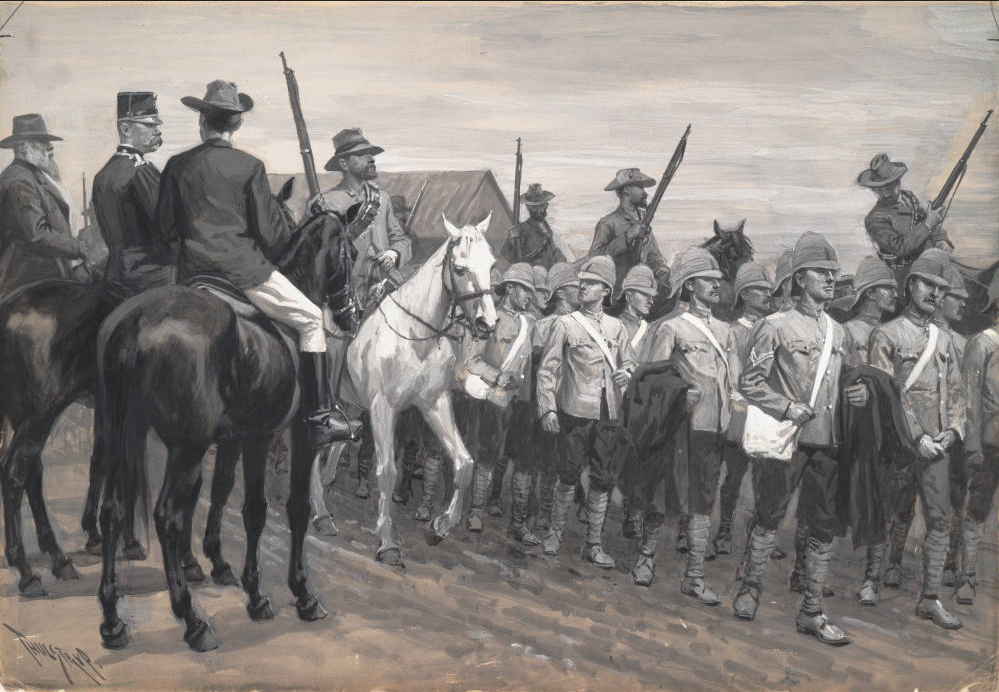

It began with a night attack on a field-cornet’s force posted at Kruger’s Post, north of Lydenburg, and here the enemy succeeded in capturing 35 men and a quantity of “impedimenta;” the field-cornet in question, although warned in time, having taken no proper precautions. By the middle of April the enemy’s forward movement was in full swing. General Plumer came from Pietersburg, General Walter Kitchener from Lydenburg, and General Barber from Middelburg. They approached us in six different directions, altogether a force of 25,000 men, and the whole under the supreme command of General Sir Bindon Blood.

No escape was available for us through Secoekuniland on the north, as the natives here, since the British had occupied their territory, were avowedly hostile to us. To escape, therefore, we would have to break through the enemy’s lines and also to cross the railway, which was closely guarded.

The enemy were advancing slowly from various directions. All our roads were carefully guarded, and the cordon was gradually tightening around us. We were repeatedly attacked, now on this side, now on that, the British being clearly anxious to discover our position and our strength. In a sharp skirmish with a column from Lydenburg my faithful Fighting-General Muller was severely wounded in his shoulder, and a commando of Lydenburgers had been isolated from me and driven by the enemy along Waterfal River up to Steelpoort, where they encountered hostile tribes of kaffirs. The commandant of the corps after a short defence was obliged to destroy his guns, forsake his baggage, and escape with his burghers in small groups into the mountains.

Our position was growing more critical, but I resolved to make a stand before abandoning our carts and waggons, although there seemed little hope of being able to save anything. In fact the situation was extremely perilous. As far as I could see we were entirely hemmed in, all the roads were blocked, my best officer wounded, I had barely 900 men with me, and our stock of ammunition was very limited.

I have omitted to mention that early in April, when we first got an inkling of this move I had liberated all the British officers whom I had kept as prisoners at Middelburg, and thus saved the British authorities many a D.S.O. which would otherwise have been claimed by their rescuers.

The British around us were now posted as follows: At Diepkloof on the Tautesberg to the north-west of us; at Roodekraal, between Tautesberg and Bothasberg, to the west of us; at Koebold, under Roodehoogte; at Windhoek, to the east of us; at Oshoek, to the north-east; and to the north of us between Magneetshoogte and Klip Spruit. We were positioned on Mapochsberg near Roos Senekal, about midway between Tautesberg and Steenkampsberg. We had carts, waggons, two field-pieces, and a Colt-Maxim.

We speedily discovered that we should have to leave our baggage and guns, and rely mainly on our horses and rifles. We had placed our hospitals as well as we could, one in an empty school-building at Mapochsberg with 10 wounded, under the care of Dr. Manning; the other, our only field-hospital, at Schoonpoort, under the supervision of Dr. H. Neethling. Whether these poor wounded Boers would have to be abandoned to the enemy, was a question which perplexed us considerably. If so, we should have been reduced to only one physician, Dr. Leitz, a young German who might get through with a pack-horse. Many officers and men, however, had lost all hope of escape.

It was about the 20th of April when the British approached so close that we had to fight all day to maintain our positions. I gave orders that same night that we should burn our waggons, destroy our guns with dynamite, and make a dash through the enemy’s lines, those burghers who had no horses to mount the mules of the convoy. Hereupon about 100 burghers and an officer coolly informed me that they had had enough fighting, and preferred to surrender. I was at that time powerless to prevent them doing so, so I took away all their horses and ammunition, at which they did not seem very pleased. Before dusk our camp was a scene of wild confusion. Waggons and carts were burning fiercely, dynamite was being exploded, and horseless burghers were attempting to break in the mules which were to serve them as mounts. Meanwhile a skirmish was going on between our outposts and those of the enemy.

It was a strange procession that left Mapochsberg that night in our dash through the British lines. Many Boers rode mules, whilst many more had no saddles, and no small number were trudging along on foot, carrying their rifles and blankets on their shoulders. My scouts had reported that the best way to get through was on the southern side along Steelpoort, about a quarter of a mile from the enemy’s camp at Bothasberg. But even should we succeed in breaking through the cordon around us, we still had to cross the line at Wondersfontein before daybreak, so as not to get caught between the enemy’s troops and the blockhouses.

About 100 scouts, who formed our advance-guard, soon encountered the enemy’s sentries. They turned to the right, then turned to the left; but everywhere the inquisitive “Tommies” kept asking: “Who goes there?” Not being over anxious to satisfy their curiosity, they sent round word at once for us to lie low, and we started very carefully exploring the neighbourhood. But there seemed no way out of the mess. We might have attacked some weak point and thus forced our way through, but it was still four or five hours’ ride to the railway line, and with our poor mounts we should have been caught and captured. Besides which the enemy might have warned the blockhouse garrisons, in which case we should have been caught between two fires.

No; we wanted to get through without being discovered, and seeing that this was that night hopeless, I consulted my officers and decided to return to our deserted camp, where we could take up our original positions without the enemy being aware of our nocturnal excursion.

Next morning the rising sun found us back in our old positions. We despatched scouts in all directions as usual, so as to make the enemy believe that we intended to remain there permanently, and we put ourselves on our guard, ready to repel an attack at any point on the shortest notice.

But the enemy were much too cautious, and evidently thought they had us safely in their hands. They amused themselves by destroying every living thing, and burned the houses and the crops. The whole veldt all round was black, everything seemed in mourning, the only relief from this dull monotony of colour being that afforded by the innumerable specks of khaki all around us. I believe I said there were 25,000 men there, but it now seemed to me as if there were almost double that number.

We had to wait until darkness set in before making a second attempt at escape. The day seemed interminable. Many burghers were loudly grumbling, and even some officers were openly declaring that all this had been done on purpose. Of course, these offensive remarks were pointed at me. At last the situation became too serious. I could only gather together a few officers to oppose an attack from the enemy on the eastern side, and something had to be done to prevent a general mutiny. I therefore ordered a burgher who seemed loudest in his complaints to receive 15 lashes with a sjambok, and I placed a field-cornet under arrest. After this the grumblers remained sullenly silent.

The only loophole in the enemy’s lines seemed to be in the direction of Pietersburg on the portion held by General Plumer, who seemed far too busy capturing cattle and sheep from the “bush-lancers” to surround us closely. We therefore decided to take our chance there and move away as quickly as possible in that direction, and then to bear to the left, where we expected to find the enemy least watchful. Shortly before sunset I despatched 100 mounted men to ride openly in the opposite direction to that which we intended to take, so as to divert the enemy’s attention from our scene of operations, and sat down to wait for darkness.

CHAPTER XXXIV

ELUDING THE BRITISH CORDON.

“The shades of eve were falling fast” as we moved cautiously away from Mapochsberg and proceeded through Landdrift, Steelpoort, and the Tautesberg. At 3 o’clock in the morning we halted in a hollow place where we would not be observed, yet we were still a mile and a half from the enemy’s cordon. Our position was now more critical than ever; for should the enemy discover our departure, and General Plumer hurry up towards us that morning, we should have little chance of escape.

During the day I was obliged to call all the burghers together, and to earnestly address them concerning the happenings of the previous day. I told them to tell me candidly if they had lost faith in me, or if they had any reason not to trust me implicitly, as I would not tolerate the way in which they had behaved the day before. I added:—

“If you cannot see your way clear to obey implicitly my commands, to be true to me, and to believe that I am true to you, I shall at once leave you, and you can appoint someone else to look after you. We are by no means out of the wood yet, and it is now more than ever necessary that we should be able to trust one another to the fullest extent. Therefore, I ask those who have lost confidence in me, or have any objection to my leading them, to stand out.”

No one stirred. Other officers and burghers next rose and spoke, assuring me that all the rebels had deserted the previous night, and that all the men with me would be true and faithful. Then Pastor J. Louw addressed the burghers very earnestly, pointing out to them the offensive way in which some of them had spoken of their superior officers, and that in the present difficult circumstances it was absolutely necessary that there should be no disintegration and discord amongst ourselves. I think all these perorations had a very salutary effect. But such were the difficulties that we officers had to contend with at the hands of undisciplined men who held exaggerated notions of freedom of action and of speech, and I was not the only Boer officer who suffered in this respect.

About two in the afternoon I gave the order to saddle up, as it was necessary to start before sunset in order to be able to cross the Olifant’s River before daybreak, so that the enemy should not overtake us should they notice us. We dismounted and led our horses, for we had discovered that the English could not distinguish between a body of men leading their horses and a troop of cattle, so long as the horses were all kept close together. All the hills around us were covered with cattle captured from our “bush-lancers,” and therefore our passage was unnoticed.

We followed an old waggon track along the Buffelskloof, where a road leads from Tautesberg to Blood River. The stream runs between Botha’s and Tautesbergen, and flows into the Olifant’s River near Mazeppa Drift. It is called Blood River on account of the horrible massacre which took place there many years before, when the Swazi kaffirs murdered a whole kaffir tribe without distinction of age or sex, literally turning the river red with blood.

Towards evening we reached the foot of the mountains, and moved in a north-westerly direction past Makleerewskop. We got through the English lines without any difficulty along some footpaths, but our progress was very slow, as we had to proceed in Indian file, and we had to stop frequently to see that no one was left behind. The country was thickly wooded, and frequently the baggage on the pack-horses became entangled with branches of trees, and had to be disentangled and pulled off the horses’ backs, which also caused considerable delay.

It was 3 o’clock in the morning before we reached the Olifant’s River, at a spot which was once a footpath drift, but was now washed away and overgrown with trees and shrubs, making it very difficult to find the right spot to cross. Our only guide who knew the way had not been there for 15 years, but recognised the place by some high trees which rose above the others. We had considerable difficulty in crossing, the water reaching to our horses’ saddles, and the banks being very steep. By the time we had all forded the sun had risen. All the other drifts on the river were occupied by the enemy, our scouts reporting that Mazeppa Drift, three miles down stream, was entrenched by a strong English force, as was the case with Kalkfontein Drift, a little higher up. I suppose this drift was not known to them, and thus had been left unguarded.

Having got through we rode in a northerly direction until about 9 o’clock in the morning, and not until then were we sure of being clear of the enemy’s clutches. But there was a danger that the English had noticed our absence and had followed us up. I therefore sent out scouts on the high kopjes in the neighbourhood, and not until these had reported all clear did we take the risk of off-saddling. You can imagine how thankful we were after having been in the saddle for over 19 hours, and I believe our poor animals were no less thankful for a rest.

We had not slept for three consecutive nights, and soon the whole commando, with the exception of the sentries, were fast asleep. Few of us thought of food, for our fatigue and drowsiness were greater than our hunger. But we could only sleep for two hours, for we were much too close to the enemy, and we wished to make them lose scent of us entirely.

The burghers grumbled a good deal at being awakened and ordered to saddle up, but we moved on nevertheless. I sent some men to enquire at a kaffir kraal for the way to Pietersburg, and although I had no intention of going in that direction, I knew that the kaffirs, so soon as we had gone, would report to the nearest British camp that they had met a commando of Boers going there. Kaffirs would do this with the hope of reward, which they often received in the shape of spirituous liquor. We proceeded all that day in the direction of Pietersburg until just before sunset we came to a small stream. Here we stopped for an hour and then went on again, this time, however, to the left in a southerly direction through the bush to Poortjesnek near Rhenosterkop, where a little time before the fight with General Paget’s force had taken place. We had to hurry through the bush, as horse-sickness was prevalent here and we still had a long way before us. It was midnight before we reached the foot of the Poortjesnek.

Here my officers informed me that two young burghers had become insane through fatigue and want of sleep, and that several, while asleep in their saddles had been pulled off their horses by low branches and severely injured. Yet we had to get through the Nek and get to the plateau before I could allow any rest. I went and had a look at the demented men. They looked as if intoxicated and were very violent. All our men and horses were utterly exhausted, but we pushed on and at last reached the plateau, where, to everybody’s great delight, we rested for the whole day. The demented men would not sleep, but I had luckily some opium pills with me and I gave each man one of them, so that they got calmer, and, dropping off to sleep, afterwards recovered.

My scouts reported next day that a strong English patrol had followed us up, but that otherwise it was “all serene.” We pushed on through Langkloof over our old fighting ground near Rhenosterkop, then through the Wilge River near Gousdenberg up to Blackwood Camp, about nine miles north of Balmoral Station. Here we stayed a few days to allow our animals to rest and recover from their hardships, and then moved on across the railway to the Bethel and Ermelo districts. Here the enemy was much less active, and we should have an opportunity of being left undisturbed for a little time. But we lost 40 of our horses, who had caught the dreaded horse-sickness whilst passing through the bush country.

On the second day of our stay at Blackwood Camp I sent 150 men under Commandants Groenwald and Viljoen through the Banks, via Staghoek, to attack the enemy’s camp near Wagendrift on the Olifant’s River. This was a detachment of the force which had been surrounding us. We discovered that they were still trying to find us, and that the patrol which had followed us were not aware of our having got away. It appears that they only discovered this several days afterwards, and great must have been the good general’s surprise when they found that the birds had flown and their great laid schemes had failed.

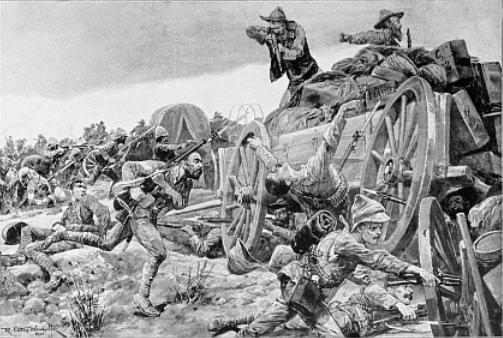

My 150 men approached the enemy’s camp early in the morning, and when at a short range began pouring in a deadly rifle fire on the western side. The British soldiers, who were not dreaming of an attack, ran to and fro in wild disorder. Our burghers, however, ceased firing when they saw that there were many women and children in the camp, but the enemy began soon to pour out a rifle and gun fire, and our men were obliged to carry on the fight.

After a few days’ absence they returned to our camp and reported to me that “they had frightened the English out of their wits, for they thought we were to the east at Roos Senekal, whereas we turned up from the west.”

Of course the British speedily discovered where we were, and came marching up from Poortjesnek in great force. But we sent out a patrol to meet them, and the latter by passing them west of Rhenosterkop effectually misled them, and we were left undisturbed at Blackwood Camp.

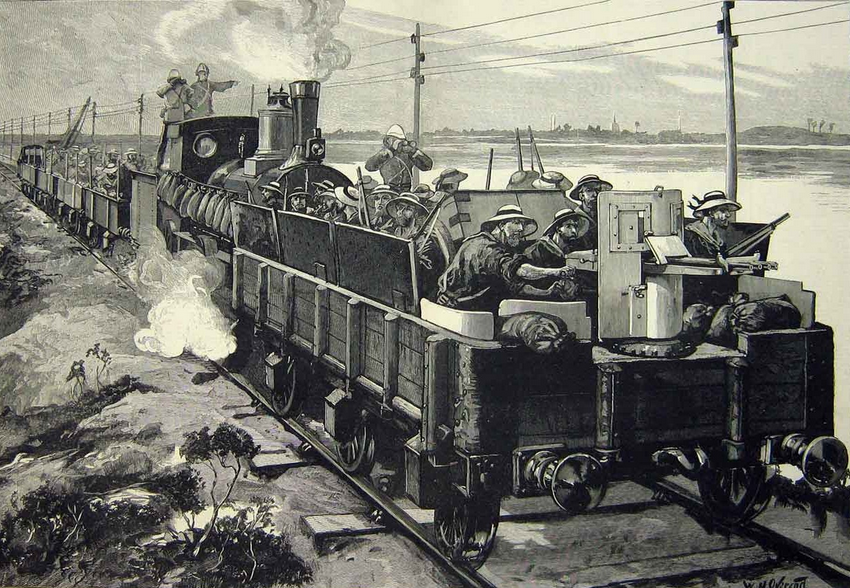

This left us time to prepare for crossing the railway; so I despatched scouts south to see how matters stood, and bade them return the next day. We knew that a number of small commandos were located on the south side of the railway, but to effect a junction was a difficult matter, and we would risk getting trapped between the columns if we moved at random. The railway and all the roads were closely guarded, and great care was being taken to prevent any communication between the burghers on either side of the line.

CHAPTER XXXV

BOER GOVERNMENT’S NARROW ESCAPE.

During the first week of May, 1901, we split up into two sections, and left Blackwood Camp early in the evening. General Muller took one section over the railway line near Brugspruit, whilst I took the other section across near Balmoral Station. We naturally kept as far from the blockhouses as possible, quietly cut the barbed-wire fences stretched all along the line, and succeeded in crossing it without a shot being fired. To split up into two sections was a necessary precaution, first because it would have taken the whole commando too long to cross the line at one point, and secondly, we made more sure of getting at least one section across. Further, had the enemy encountered one of the sections they would probably have concluded that that was our whole force.

We halted about six miles from the railway-line, as it was now 2 o’clock in the morning. I ordered a general dismount, and we were at last able to light up our pipes, which we had been afraid of doing in the neighbourhood of the railway for fear of the lights being seen by the enemy. The men sat round in groups, and smoked and chatted cheerfully. We passed the rest of the night here, and with the exception of the sentinels on duty, all were able to enjoy a refreshing sleep, lying down, however, with their unsaddled horses by their side, and the bridles in their hands—a most necessary and useful precaution. Together with my adjutant, Nel, I made the round of the sentries, sitting a few moments with each to cheer them up and keep them awake; for there is nothing to which I object more than to be surprised by the enemy, when asleep.

The few hours of rest afforded us passed very quickly, and at the first glimmer of dawn I ordered the men to be called. This is simply done by the officers calling “Opzâal, opzâal” (saddle-up) in loud tones. When it was light enough to look round us we had the satisfaction of seeing that all was quiet and that no troops were in the immediate neighbourhood. We made for a place called Kroomdraai, about halfway between Heidelberg and Middelburg, where we knew there were some mealies left; and although we should be between the enemy’s camps there, I felt there would be no danger of being disturbed or surprised.

I also sent a report to the Commandant-General, who was at that time with the Government near Ermelo, and described to him all that had happened. I received a reply some days later, requesting me to leave my commando at Kroomdraai and proceed to see him, as an important Council of War was to be held between the various generals and the Government.

Four days later I arrived at Begin der Lijn (“beginning of the line”) on the Vaal River, south-east of Ermelo, accompanied by three of my adjutants, and reported myself to the Commandant-General.

Simultaneously with my arrival there came two British columns, commanded by our old friend Colonel Bullock, whose acquaintance we had previously made at Colenso. They came apparently with the idea of chasing us, possibly thinking to catch us. This was far from pleasant for me. I had been riding post-haste for four days, and I and my horse were very tired and worn out. However, there was no help for it. I had barely time to salute the members of the Government, and to exchange a few words with General Botha, when we had to “quit.” For eight days we wandered round with Colonel Bullock at our heels, always remaining, however, in the same neighbourhood. This officer’s tactics in trying to capture us were childishly simple. During the day there would be skirmishes between the enemy and General Botha’s men, but each evening the former would, by retiring, attempt to lull us into a sense of security. But as soon as the sun had set, they would turn right about face, return full speed to where they had left us, and there would surround us carefully during the night, gallantly attacking us in the morning and fully expecting to capture the whole Boer Government and at least half a dozen generals. This was a distinct nuisance, but the tactics of this worthy officer were so simple that we very soon discovered them. Accordingly, every evening we would make a fine pretence of pitching our camp for the night; but so soon as darkness had set in, we would take the precaution of moving some 10 or 15 miles further on. Next morning Colonel Bullock, who had been carefully “surrounding” us all night, would find that we were unaccountably absent. Much annoyed at this, he would then send his “flying” columns running after us. This went on for several days, until finally, as we expected, his horses were tired out, and I believe he was then removed to some other garrison, having been considered a failure as a “Boer-stalker.” No doubt he did his best, but he nevertheless managed his business very clumsily.

Not until nine days after my arrival at this perambulating seat of Government did we have an opportunity of snatching a few hours’ rest. We were now at a spot called Immegratie, between Ermelo and Wakkerstroom. Here a meeting was held by the Executive Council, and attended by the Commandant-General, General Jan Smuts, General C. Botha, and myself. General T. Smuts could not be present, as he was busy keeping Colonel Bullock amused.

At this meeting we discussed the general situation, and decided to send a letter to President Steyn, but our communication afterwards fell into the enemy’s hands. In accordance with this letter, President Steyn and Generals De Wet and De la Rey joined our Government, and a meeting was held later on.

The day after this meeting at Immegratie I took leave of my friends and began the journey in a more leisurely fashion back to my commando at Kroomdraai, via Ermelo and Bethel. The Acting-President had made me a present of a cart and four mules, as they pitied us for having had to burn all our vehicles in escaping from Roos Senekal. We were thus once more seated in a cart, which added considerably to the dignity of our staff. How long I should continue to be possessed of this means of transport depended, of course, entirely on the enemy. My old coloured groom “Mooiroos,” who followed behind leading my horse, evidently thought the same, for he remarked naïvely: “Baas, the English will soon fix us in another corner; had we not better throw the cart away?”

We drove into Ermelo that afternoon. The dread east wind was blowing hard and raising great clouds of dust around us. The village had been occupied about half a dozen times by the enemy and each time looted, plundered, and evacuated, and was now again in our possession. At least, the English had left it the day before, and a Landdrost had placed himself in charge; a little Hollander with a pointed nose and small, glittering eyes, who between each sentence that he spoke rolled round those little eyes of his, carefully scanning the neighbouring hills for any sign of the English. The only other person of importance in the town was a worthy predicant, who evidently had not had his hair cut since the commencement of the War, and who had great difficulty in keeping his little black wide-awake on his head. He seemed very proud of his abundant locks.

There were also a few families in the place belonging to the Red Cross staff and in charge of the local hospitals. One of my adjutants was seriously indisposed, and it was whilst hunting for a chemist in order to obtain medicine that I came into contact with the town’s sparse population. I found the dispensary closed, the proprietor having departed with the English, and the Landdrost, fearing to get himself into trouble, was not inclined to open it. He grew very excited when we liberally helped ourselves to the medicines, and made himself unpleasant. So we gave him clearly to understand that his presence was not required in that immediate neighbourhood.

Our cart was standing waiting for us in the High Street, and during our absence a lady had appeared on the verandah of a house and had sent a servant to enquire who we were. When we reappeared laden with our booty she graciously invited us to come in. She was a Mrs. P. de Jager and belonged to the Red Cross Society. She asked us to stay and have some dinner, which was then being prepared. Imagine what a luxury for us to be once more in a house, to be addressed by a lady and to be served with a bountiful repast! Our clothes were in a ragged and dilapidated condition and we presented a very unkempt appearance, which did not make us feel quite at our ease. Still the good lady with great tact soon put us quite at home.

We partook of a delicious meal, which we shall not easily forget. I cannot remember what the menu was, and I am not quite sure whether it would compare favourably with a first-class café dinner, but I never enjoyed a meal more in my existence, and possibly never shall.

After dinner the lady related to us how on the previous day, when the British entered the village, there were in her house three convalescent burghers, who could, however, neither ride nor walk. With tears in her eyes she told us how an English doctor and an officer had come there, and kicking open the doors of her neatly-kept house, had entered it, followed by a crowd of soldiers, who had helped themselves to most of the knives, forks, and other utensils. She tried to explain to the doctor that she had wounded men in the house, but he was too conceited and arrogant to listen to her protestations. Fortunately for them the men were not discovered, for the English, on leaving the village, took with them all our wounded, and even our doctor. With a proud smile she now produced this trio, who, not knowing whether we were friend or foe, were at first very much frightened.

I sympathised with the lady with respect to the harsh treatment she had received the previous day, and thanking her for her great kindness, warned her not to keep armed burghers in her house, as this was against the Geneva Convention.

We told her what great pleasure it was for us to meet a lady, as all our women having been placed in Concentration Camps, we had only had the society of our fellow-burghers. Before leaving she grasped our hands, and with tears in her eyes wished us God speed:—”Good-bye, my friends! May God reward your efforts on behalf of your country. General, be of good cheer; for however dark the future may seem, be sure that the Almighty will provide for you!” I can scarcely be dubbed sentimental, yet the genuine expressions of this good lady, coupled perhaps with her excellent dinner, did much to put us into better spirits, and somehow the future did not seem now quite so dark and terrible as we were previously inclined to believe.

We soon resumed our journey, and that night arrived at a farm belonging to a certain Venter. We knew that here some houses had escaped the general destruction and we found that a dwelling house was still standing and that the Venter family were occupying it. It was not our practice to pass the night near inhabited houses, as that might have got the people in trouble with the enemy, but having off-saddled, I sent up an adjutant to the house to see if he could purchase a few eggs and milk for our sick companions. He speedily returned followed by the lady of the house in a very excited condition:—

“Are you the General?” she asked.

“I have that honour,” I replied. “What is the matter?”

“There is much the matter,” she retorted loudly. “I will have nothing to do with you or your people. You are nothing but a band of brigands and scoundrels, and you must leave my farm immediately. All respectable people have long since surrendered, and it is only such people as you who continue the War, while you personally are one of the ringleaders of these rebels.”

“Tut, tut,” I said, “where is your husband?”

“My husband is where all respectable people ought to be; with the English, of course.”

“‘Hands-uppers,’ is that it?” answered my men in chorus, even Mooiroos the native joining in. “You deserve the D.S.O.,” I said, “and if we meet the English we will mention it to them. Now go back to your house before these rebels and brigands give you your deserts.”

She continued to pour out a flood of insults and imprecations on myself, the other generals, and the Government, and finally went away still muttering to herself. I could scarcely help comparing this patriotic lady to the one in Ermelo who had treated us so kindly. I encountered many more such incidents, and only mention these two in order to show the different views held at that time by our women on these matters, but in justice to our women-folk I should add that this kind were only a small minority.

It was a bitterly cold night. Our blankets were very thin, and the wind continually scattered our fire and gave us little opportunity of warming ourselves. There was no food for the horses except the grass. We haltered them close together, and each of us took it in turn to keep a watch, as we ran the risk at any moment of being surprised by the enemy, and as many in that district had turned traitors, we had to redouble our precautions. During the whole cold night I slept but little, and I fervently wished for the day to come, and felt exceedingly thankful when the sun arose and it got a little warmer.

Proceeding, we crossed the ridges east of Bethel, and as this village came in sight my groom Mooiroos exclaimed: “There are a lot of Khakis there, Baas.”

I halted, and with my field-glasses could see distinctly the enemy’s force, which was coming from Bethel in our direction, their scouts being visible everywhere to the right and left of the ridges. While we were still discussing what to do, the field-cornet of the district, a certain Jan Davel, dashed up with a score of burghers between us and the British. He informed me that the enemy’s forces were coming from Brugspruit, and that he had scattered his burghers in all directions to prevent them organizing any resistance. The enemy’s guns were now firing at us, and although the range was a long one the ridges in which we found ourselves were quite bare, and afforded us no cover.

We were therefore obliged to wheel to our right, and, proceeding to Klein Spionkop, we passed round the enemy along Vaalkop and Wilmansrust.

At Steenkoolspruit I met some burghers, who told me that the enemy had marched from Springs, near Boksburg, and were making straight for our commando at Kroomdraai. We managed to reach that place in the evening just in time to warn our men and be off. I left a section of my men behind to obstruct the advance of the enemy, whom they met the following day, but finding the force too strong were obliged to retire, and I do not know exactly where they got to. At this time there were no less than nine of the enemy’s columns in that district, and they all tried their level best to catch the Boers, but as the Boers also tried their best not to get caught, I am afraid the English were often disappointed. Here the reader will, perhaps, remark that it was not very brave to run away in this fashion, but one should also take our circumstances into consideration.

No sooner did we attack one column than we were attacked in our turn by a couple more, and had then considerable difficulty in effecting our escape. The enemy, moreover, had every advantage of us. They had plenty of guns, and could cut our ranks to pieces before we could approach sufficiently near to do any damage with our rifles; they far surpassed us in numerical strength; they had a constant supply of fresh horses—some of us had no horses at all; they had continual reinforcements; their troops were well fed, better equipped, and altogether in better condition. Small wonder, therefore, that the War had become a one-sided affair.

On the 20th of May, 1901, I seized an opportunity of attacking General Plumer on his way from Bethel to Standerton.

We had effected a junction with Commandant Mears and charged the enemy, and but for their having with them a number of Boer families we would have succeeded in capturing their whole laager. We had already succeeded in driving their infantry away from the waggons containing these families, when their infantry rushed in between and opened fire on us at 200 paces. We could do nothing else but return this fire, although it was quite possible that in doing so we wounded one or two of our own women and children. These kept waving their handkerchiefs to warn us not to fire, but it was impossible to resist the infantry’s volleys without shooting. Meanwhile the cavalry replaced their guns behind the women’s waggons and fired on us from that coign of vantage.

Here we took 25 prisoners, 4,000 sheep and 10 horses. Our losses were two killed and nine wounded. The enemy left several dead and wounded on the field, as well as two doctors and an ambulance belonging to the Queensland Imperial Bushmen, which we sent back together with the prisoners we had taken.

On this occasion the English were spared a great defeat by having women and children in their laager, and no doubt for the sake of safety they kept these with them as long as possible. I do not insinuate that this was generally the case, and I am sure that Lord Kitchener or any other responsible commanding officer would loudly have condemned such tactics; but the fact remains that these unpleasant incidents occasionally took place.

About the beginning of June, 1901 (I find it difficult to be accurate without the aid of my notes) another violent effort was made to capture the members of the Government and the Commandant-General. Colonel Benson now appeared as the new “Boer-stalker,” and after making several unsuccessful attempts to surround them almost captured the Government in the mountains between Piet Retief and Spitskop. Just as Colonel Benson thought he had them safe and was slowly but surely weaving his net around them—I believe this was at Halhangapase—the members of the Government left their carriages, and packing the most necessary articles and documents on their horses escaped in the night along a footpath which the enemy had kindly left unguarded and passed right through the British lines in the direction of Ermelo. On the following day the English, on closing their cordon, found, as they usually did, naught but the burned remains of some vehicles and a few lame mules.

Together with the late General Spruit, who happened to be in that neighbourhood, I had been asked to march with a small commando to the assistance of the Government and the Commandant-General and we had started at once, only hearing when well on our way that they had succeeded in escaping.

We proceeded as far as the Bankop, not knowing where to find them, and it was no easy matter to look for them amongst the British columns.

CHAPTER XXXVI

A GOVERNMENT ON HORSEBACK.

For ten days we searched the neighbourhood, and finally met one of the Commandant-General’s despatch-riders, who informed me of their whereabouts, which they were obliged to keep secret for fear of treachery. We met the whole party on William Smeet’s farm near the Vaal River, every man on horseback or on a mule, without a solitary cart or waggon. It was a very strange sight to see the whole Transvaal Government on horseback. Some had not yet got used to this method of governing, and they had great trouble with their luggage, which was continually being dropped on the road.

General Spruit and myself undertook to escort the Executive Council through the Ermelo district, past Bethel to Standerton, where they were to meet the members of the Orange Free State Government. I had now with me only 100 men, under Field-Cornet R. D. Young; the remainder I had left behind near Bethel in charge of General Muller and Commandants Viljoen and Groenwald, with instructions to keep on the alert and to fall on any column that ventured a little ahead of the others.

It was whilst on my way back to them that a burgher brought me a report from General Muller, informing me that the previous night, assisted by Commandants W. Viljoen and Groenwald, he had with 130 men stormed one of the enemy’s camps at Wilmansrust, capturing the whole after a short resistance on the enemy’s part, but sustaining a loss of six killed and some wounded. The camp had been under the command of Colonel Morris, and its garrison numbered 450 men belonging to the 5th Victorian Mounted Rifles. About 60 of these were killed and wounded, and the remainder were disarmed and released. Our haul consisted of two pom-poms, carts and waggons with teams in harness, and about 300 horses, the most miserable collection of animals I have ever seen. Here we also captured a well-known burgher, whose name, I believe, was Trotsky, and who was fighting with the enemy against us. He was brought before a court-martial, tried for high treason, and sentenced to death, which sentence was afterwards carried out.

Our Government received about this time a communication from General Brits, that the members of the Orange Free State Government had reached Blankop, north of Standerton, and would await us at Waterval. We hurried thither, and reached it in the evening of the 20th of June, 1901. Here we found President Steyn and Generals De Wet, De la Rey, and Hertzog, with an escort of 150 men. It was very pleasant to meet these great leaders again, and still more pleasing was the cordiality with which they received us. We sat round our fires all that night relating to each other our various adventures. Some which caused great fun and amusement, and some which brought tears even to the eyes of the hardened warrior. General De Wet was then suffering acutely from rheumatism, but he showed scarcely any trace of his complaint, and was as cheerful as the rest of us.

Next day we parted, each going separately on our way. We had decided what each of us was to do, and under this agreement I was to return to the Lydenburg and Middelburg districts, where we had already had such a narrow escape. I confess I did not care much about this, but we had to obey the Commandant-General, and there was an end of it. Meanwhile, reports came in that on the other side of the railway the burghers who had been left behind were surrendering day by day, and that a field-cornet was engaged in negotiations with the enemy about a general laying down of arms. I at once despatched General Muller there to put an end to this.

We now prepared once more to cross the railway line, which was guarded more carefully than ever, and no one dared to cross with a conveyance of any description. We had, however, become possessed of a laager—a score of waggons and two pom-poms—and I determined to take these carts and guns across with me, for my men valued them all the more for having been captured. They were, in fact, as sweet to us as stolen kisses, although I have had no very large experience of the latter commodity.

CHAPTER XXXVII

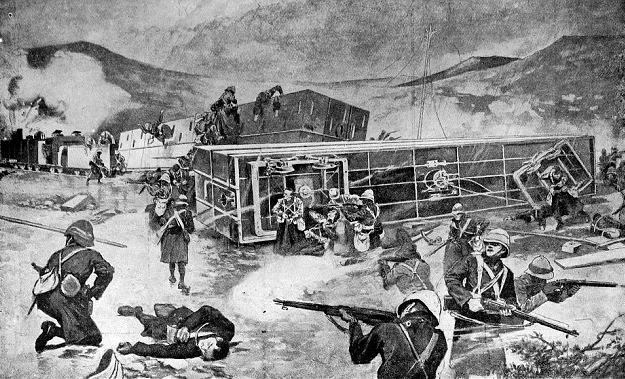

BLOWING UP AN ARMOURED TRAIN.

We approached the line between Balmoral and Brugspruit, coming as close to it as was possible with regard to safety, and we stopped in a “dunk” (hollow place) intending to remain there until dusk before attempting to cross. The blockhouses were only 1,000 yards distant from each other, and in order to take our waggons across there was but one thing to be done, namely, to storm two blockhouses, overpower their garrisons, and take our convoy across between these two. Fortunately there were no obstacles here in the shape of embankments or excavations, the line being level with the veldt. We moved on in the evening (the 27th of June), the moon shining brightly, which was very unfortunate for us, as the enemy would see us and hear us long before we came within range. I had arranged that Commandant Groenwald was to storm the blockhouse on the right, and Commandant W. Viljoen that to the left, each with 75 men. We halted about 1,000 paces from the line, and here the sections left their horses behind and marched in scattered order towards the blockhouses. The enemy had been warned by telephone that morning of our vicinity, and all the pickets and outposts along the line were on the “qui vive.” When 150 yards from the blockhouses the garrison opened fire on our men, and a hail of Lee-Metford bullets spread over a distance of about four miles, the British soldiers firing from within the blockhouses and from behind mounds of earth. The blockhouse attacked by Commandant Viljoen offered the most determined resistance for about twenty minutes, but our men thrust their rifles through the loopholes of the blockhouses and fired within, calling out “hands-up” all the time, whilst the “Tommies” within retorted, “You haven’t V.M.R.’s to deal with this time!” However, we soon made it too hot for them and their boasting was exchanged into cries of mercy, but not before three of our men had been killed and several wounded. The “Tommies” now shouted: “We surrender, Sir; for God’s sake stop firing.” My brave field-cornet, G. Mybergh, who was closest to the blockhouses, answered: “All right then, come out.” The “Tommies” answered: “Right, we are coming,” and we ceased firing.

Field-Cornet Mybergh now stepped up to the entrance of the fort, but when he reached it a shot was fired from the inside and he fell mortally wounded in the stomach. At the same time the soldiers ran out holding up their hands. Our burghers were enraged beyond measure at this act of treachery, but the sergeant and the men swore by all that was sacred that it had been an accident, and that a gun had gone off spontaneously whilst being thrown down. The soldier who admitted firing the fatal shot was crying like a baby and kissing the hands of his victim. We held a short consultation amongst the officers and decided to accept his explanation of the affair. I was much upset, however, by this loss of one of the bravest officers I have ever known.

Meanwhile the fight at the other blockhouse continued. Commandant Groenwald afterwards informed me that he had approached the blockhouse and found it built of rock; it was, in fact, a fortified ganger’s house built by the Netherlands South Africa Railway Company. He did not see any way of taking the place; many of his men had fallen, and an armoured train with a search-light was approaching from Brugspruit. On the other side of the blockhouse we found a ditch about three feet deep and two feet wide. Hastily filling this up we let the carts go over. As the fifth one had got across and the sixth was standing on the lines, the armoured train came dashing at full speed in our midst. We had had no dynamite to blow up the line, and although we fired on the train, it steamed right up to where we were crossing, smashing a team of mules and splitting us up into two sections. Turning the search-light on us, the enemy opened fire on us with rifles, Maxims and guns firing grape-shot. Commandant Groenwald had to retire along the unconquered blockhouse, and managed somehow to get through. The majority of the burghers had already crossed and fled, whilst the remainder hurried back with a pom-pom and the other carts. I did not expect that the train would come so close to us, and was seated on my horse close to the surrendered blockhouse when it pulled up abruptly not four paces from me. The search-light made the surroundings as light as day, and revealed the strange spectacle of the burghers, on foot and on horseback, fleeing in all directions and accompanied by cattle and waggons, whilst many dead lay on the veldt. However, we saved everything with the exception of a waggon and two carts, one of which unfortunately was my own. Thus for the fourth time in the war I lost all my worldly belongings, my clothes, my rugs, my food, my money.

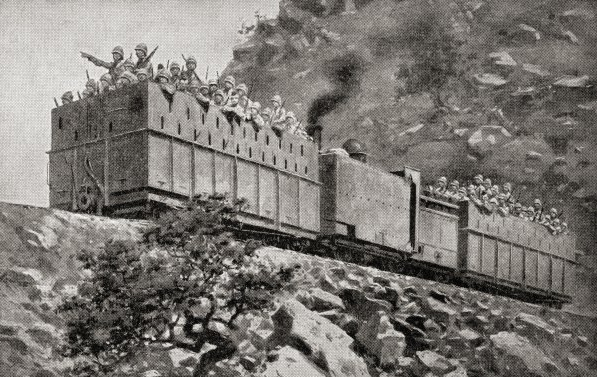

My two commandants were now south of the line with half the men, whilst I was north of it with the other half. We buried our dead next morning and that evening I sent a message to the remainder of the commandos, telling them to cross the line at Uitkijk Station, south-west of Middelburg, whilst Captain Hindon was to lay a mine under the line near the station to blow up any armoured train coming down. Here we managed to get the rest of our laager over without much trouble. The “Tommies” fired furiously from the blockhouses and our friend the armoured train was seen approaching from Middelburg, whistling a friendly warning to us. It came full speed as before, but only got to the spot where the mine had been laid for it. There was a loud explosion; something went up in the air and then the shrill whistle stopped and all was silent.

The next morning we were all once more camped together at Rooihoogte.

CHAPTER XXXVIII

TRAPPING PRO-BRITISH BOERS.

In the month of July, 1901, we found ourselves once more on the scene of our former struggles, and were joined here by General Muller, who had completed his mission south of the railway. This district having been scoured for three weeks by thirty thousand English soldiers, who had carefully removed and destroyed everything living or dead, one can imagine the conditions under which we had to exist. No doubt from a strategical point of view the enemy could not be expected to do otherwise than devastate the country, but what grieved us most was the great amount of suffering this entailed to our women and children. Often the waggons in which these were being carried to imprisonment in the Concentration Camps were upset by the unskilful driving of the soldiers or their kaffir servants, and many women and children were injured in this way.

Moreover, a certain Mrs. Lindeque was killed by an English bullet near Roos Senekal, the soldiers saying that she had passed through the outposts against instructions. Small wonder, therefore, that many of our women-folk fled with their children at the enemy’s approach, leaving all their worldly possessions behind to fall a prey to the general destruction. We often came across such families in the greatest distress, some having taken shelter in caves, and others living in huts roughly constructed of half-burnt corrugated iron amongst the charred ruins of their former happy homes. The sufferings of our half-clad and hungry burghers were small compared to the misery and privations of these poor creatures. Their husbands and other relations, however, made provision for them to the best of their ability, and these families were, in spite of all, comparatively happy, so long as they were able to remain amongst their own people.

Our commandos were now fairly exhausted, and our horses needed a rest very badly, the wanderings of the previous few weeks having reduced them to a miserable condition. I therefore left General Muller near the cobalt mines on the Upper Olifant’s River, just by the waggon drift, whilst I departed with 100 men and a pom-pom to Witpoort and Windhoek, there to collect my scattered burghers and reorganise my diminished commando, as well as to look after our food supplies. At Witpoort the burghers who had been under the late Field-Cornet Kruge, and had escaped the enemy’s sweeping movements, had repaired the mill which the English had blown up, and this was now working as well as before. A good stock of mealies had been buried there, and had remained undiscovered, and we were very thankful to the “bush-lancers” for this bounty.

Still, things were not altogether “honey.” Matters were rather in a critical state, as treachery was rampant, and many burghers were riding to and fro to the enemy and arranging to surrender, the faithful division being powerless to prevent them. We had to act with great firmness and determination to put a stop to these tendencies and within a week of our arrival half a dozen persons had been incarcerated in Roos Senekal gaol under a charge of high treason. Moreover we effected a radical change in leadership, discharging old and war-sick officers and placing younger and more energetic men in command.

Several families here were causing considerable trouble. When first the enemy had passed through their district they had had no opportunity of surrendering with their cattle. But when the English returned, they had attempted to go to the enemy’s camp at Belfast, taking all their cattle and moveables with them. At this the loyal burghers were furious and threatened to confiscate all their cattle and goods. Seeing this, these families, whom I shall call the Steenkamps, had desisted from their attempt to go over to the enemy and had taken up their abode in a church at Dullstroom, the only building which had not been destroyed, although the windows, doors and pulpit had long disappeared. Here they quietly awaited an opportunity of surrendering to the enemy, whose camp at Belfast was only 10 or 12 miles distant. We were very anxious that their cattle and sheep, of which they had a large number, should not go to the enemy, but we could bring no charge of treachery home to them, as they were very smooth-tongued scoundrels and always swore fealty to us.

I have mentioned this as an example of the dangerous elements with which we had to contend amongst our own people, and to show how low a Boer may sink when once he has decided to forego his most sacred duties and turn against his own countrymen the weapon he had lately used in their defence. Such men were luckily in the minority. Yet I often came across cases where fathers fought against their own sons, and brother against brother. I cannot help considering that it was far from noble on the part of our enemy to employ such traitors to their country and to form such bodies of scoundrels as the National Scouts.

Amongst all this worry of reorganising our commandos and weeding out the traitors we were allowed little rest by the enemy, and once we suddenly found them marching up from Helvetia in our direction. A smart body of men, chiefly composed of Lydenburg and Middelburg men, and under the command of a newly-appointed officer, Captain Du Toit, went to meet the enemy between Bakendorp and Dullstroom. Here ensued a fierce fight, where we lost some men, but succeeded in arresting the enemy’s progress. The fight, however, was renewed the next day, and the British having received strong reinforcements our burghers were forced to retire, the enemy remaining at a place near the “Pannetjes,” three miles from Dullstroom.

The English camp was now close to our friends, the Steenkamps, who were anxiously waiting an opportunity to become “hands-uppers.” They had, of course, left off fighting long ago, one complaining that he had a disease of the kidneys, another that he suffered from some other complaint. They would sit on the kopjes and watch the fighting and the various manœuvres, congratulating each other when the enemy approached a little nearer to them.

I will now ask the reader’s indulgence to describe one of our little practical jokes enacted at Dullstroom Church, which was characteristic of many other similar incidents in the Campaign. It will be seen how these would-be “hands-uppers” were caught in a little trap prepared by some officers of my staff.

My three adjutants, Bester, Redelinghuisen, and J. Viljoen, carefully dressed in as much “khaki” as they could collect, and parading respectively as Colonels Bullock, “Jack,” and “Cooper,” all of His Majesty’s forces, proceeded one fine evening to Dullstroom Church, to ascertain if the Steenkamps would agree to surrender and fight under the British flag. They arrived there about 9 p.m., and finding that the inmates had all gone to sleep, loudly knocked at the door. This was opened by a certain youthful Mr. Van der Nest, who was staying in the church for the night with his brother. J. Viljoen, alias “Cooper,” and acting as interpreter between the pseudo-English and the renegade Boers, addressed the young man in this fashion:—

“Good evening! Is Mr. Steenkamp in? Here is a British officer who wishes to see him and his brother-in-law.”

Van der Nest turned pale, and hurried inside, and stammering, “Oom Jan, there are some people at the door,” woke up his brother and both decamped out of the back door. Steenkamp’s brother-in-law, however, whom I will call Roux, soon made his appearance and bowing cringingly, said with a smile:—

“Good evening, gentlemen; good evening.”

The self-styled Colonel Bullock, addressing “Cooper,” the interpreter, said: “Tell Mr. Roux that we have information that he and his brother wish to surrender.”

As soon as “Cooper” began to interpret, Roux answered in broken English, “Yes, sir, you are quite right; myself and my brother-in-law have been waiting twelve months for an opportunity to surrender, and we are so thankful now that we are able to do so.”

“Colonel Bullock”: “Very well, then; call your people out!”

Roux bowed low, and ran back into the church, presently issuing with three comrades, who all threw down their arms and made abeyance.

The “Colonel”: “Are these men able to speak English?”

Roux: “No, sir.”

The “Colonel”: “Ask them if they are willing to surrender voluntarily to His Majesty the King of Great Britain?”

The burghers, in chorus: “Yes, sir; thank you very much. We are so pleased that you have come at last. We have wished to surrender for a long time, but the Boers would not let us get through. We have not fought against you, sir.”

The “Colonel”: “Very well; now deliver up all your arms.”

And whilst the pseudo-colonel pretended to be busy making notes the burghers brought out their Mausers and cartridge-belts, handing them over to the masquerading “Tommies.”

Roux next said to the “Colonel”: “Please, sir, may I keep this revolver? There are a few Hollanders in the hut yonder who said they would shoot me if I surrendered; and you know, sir, that it is these Hollanders who urge the Boers to fight and prolong the War. Why don’t you go and catch them? I will show you where they are.”

Resisting an impulse to put a bullet through the traitor’s head, the “Colonel” answered briefly: “Very well, keep your revolver. I will catch the Hollanders early to-morrow.”

Roux: “Be careful, sir; Ben Viljoen is over there with a commando and a pom-pom.”

The “Colonel” (haughtily): “Be at ease; my column will soon be round him and he will not escape this time.”

The women-folk now came out to join the party. They clapped their hands in joy and invited the “Colonel” and his men to come in and have some coffee.

The “Colonel” graciously returned thanks. Meanwhile a woman had whispered to Roux: “I hope these are not Ben Viljoen’s people making fools of us.”

“Nonsense,” he answered, “Can’t you see that this is a very superior British officer?” Whereat the whole company further expressed their delight at seeing them.

The “Colonel” now spoke: “Mr. Roux, we will take your cattle and sheep with us for safety. Kindly lend us a servant to help drive them along. Will you show us to-morrow where the Boers are?”

Mr. Roux: “Certainly, sir, but you must not take me into dangerous places, please.”

The “Colonel”: “Very well; I will send the waggons to fetch your women-folk in the morning.”

Roux gathered together his cattle and said: “I hope you and I shall have a whiskey together in your camp to-morrow.”

The “Colonel” answered: “I shall be pleased to see you,” and asked them if they had any money or valuables they wished taken care of. But the Boers, true to the saying, “Touch a Boer’s heart rather than his purse,” answered in chorus: “Thank you, but we have put all that carefully away where no Boer will find it.”

They all bid the “Colonel” good-bye, the “Tommies” exchanging some familiarities with the women till these screamed with laughter, and then the “Colonel” and his commando of two men remounted their big clumsy English horses and rode proudly away. But pride comes before a fall, and they had not proceeded many yards when the “Colonel’s” horse, stumbling over a bundle of barbed wire, fell, and threw his rider to the ground. Just as he had nearly exhausted the Dutch vocabulary of imprecations, the Steenkamps, who fortunately had not heard him, came to his assistance and with many expressions of sympathy helped him on his horse, Roux carefully wiping his leggings clean with his handkerchief. After proceeding a little further the “Tommies” asked their “Colonel” what he meant by that acrobatic performance. Whereat the “Colonel” answered: “That was a very fortunate accident; the Steenkamps are now convinced that we are English by the clumsy manner I rode.”

The next morning my three adjutants arrived in camp carrying four new Mausers and 100 cartridges each, and driving about 300 sheep and a nice pony. The same morning I sent Field-Cornet Young to arrest the brave quartette of burghers. He found everything packed in readiness to depart to the English camp, and they were anxiously awaiting Colonel Bullock’s promised waggons.

It was, of course, a fine “tableau” when the curtain rose on the farce, disclosing in the place of the expected English rescuers a burgher officer with a broad smile on his face. They were, of course, profuse in their apologies and excuses. They declared that they had been surrounded by hundreds of the enemy who had placed their rifles to their breasts, forcing them to surrender. One of them was now in so pitiable a condition of fear that he showed the field-cornet a score of certificates from doctors and quacks of all sorts, declaring him to be suffering from every imaginable disease, and the field-cornet was moved to leave him behind. The other three were placed under arrest, court-martialled and sentenced to three months’ hard labour, and to have all their goods confiscated.

Two days later the English occupied Dullstroom, and the pseudo-invalid and the women, minus their belongings, were taken care of by the enemy, as they had wished.

CHAPTER XXXIX

BRUTAL KAFFIRS’ MURDER TRAIL.

At Windhoek we were again attacked by an English column. The reader will probably be getting weary of these continual attacks, and I hasten to assure him that we were far more weary than he can ever grow. On the first day of the fight we succeeded in forcing back the enemy, but on the second day, the fortunes of war were changed and after a fierce fight, in which I had the misfortune to lose a brave young burgher named Botha, we gave up arguing the matter with our foes and retired.

The enemy followed us up very closely, and although I used the sjambok freely amongst my men I could not persuade them, not even by this ungentle method, to make a stand against their foes, and as we passed Witpoort the enemy’s cavalry with two guns was close at our heels.

Not until the burghers had reached Maagschuur, between the Bothas and Tautesbergen, would they condescend to make a stand and check the enemy’s advance. Here after a short but sharp engagement, we forced them to return to Witpoort, where they pitched camp.

Our mill, which I have previously mentioned as being an important source of our food supply, was again burned to the ground.

Our commandos returned to Olifant’s River and at the cobalt mine near there joined those who had remained behind under General Muller. The enemy, however, who seemed determined, if possible, to obliterate us from the earth’s surface, discovered our whereabouts about the middle of July, and attacked us in overwhelming numbers. We had taken up a position on the “Randts,” and offered as much resistance as we could. The enemy poured into us a heavy shell fire from their howitzers and 15-pounders, while their infantry charged both our extreme flanks. After losing many men, a battalion of Highlanders succeeded in turning our left flank, and once having gained this advantage, and aided by their superior numbers, the enemy were able to take up position after position, and finally rendered it impossible to offer any further resistance. Late in the afternoon, with a loss of five wounded and one man killed—an Irish-American, named Wilson—we retired through the Olifant’s River, near Mazeppa Drift, the enemy staying the night at Wagendrift, about three miles further up the stream. The following morning they forded the river, and proceeded through Poortjesnek and Donkerhoek, to Pretoria, thus allowing us a little breathing space. I now despatched some reliable burghers to report our various movements to the Commandant-General, and to bring news of the other commandos. It was three weeks before these men returned, for they had on several occasions been prevented from crossing the railway line, and they finally only succeeded in doing so under great difficulties. They reported that the English on the high veldt were very active and numerous.

About the middle of July I left General Muller to take a rest with the commando, and accompanied by half a score of adjutants and despatch riders, proceeded to Pilgrimsrust in the Lydenburg district to visit the commandos there, and allay as much as I could the dissatisfaction caused by my reorganisation.

At Zwagerhoek, a kloof some 12 miles south of Lydenburg, through which the waggon track leads from Lydenburg to Dullstroom, I found a field-cornet with about 57 men. Having discussed the situation with them and explained matters, they were all satisfied.

Here I appointed as field-cornet a young man of 23 years of age, a certain J. S. Schoenman, who distinguished himself subsequently by his gallant behaviour.

We had barely completed our arrangements when we were again attacked by one of the enemy’s columns from Lydenburg. At first we successfully defended ourselves, but at last were compelled to give way.

I do not believe we caused the enemy any considerable losses, but we had no casualties. The same night we proceeded through the enemy’s line to Houtboschloop, five miles east of Lydenburg, where a small commando was situated, and having to proceed a very roundabout way, we covered that night no less than 40 miles.

Another meeting of all burghers north of Lydenburg was now convened, to be held at a ruined hotel some 12 miles west of Nelspruit Station, which might have been considered the centre of all the commandos in that district. I found that these were divided into two parties, one of which was dissatisfied with the new order of things I had arranged and desired to re-instate their old officers, while the other was quite pleased with my arrangements. The latter party was commanded by Mr. Piet Moll, whom I had appointed commandant instead of Mr. D. Schoeman, who formerly used to occupy that position. At the gathering I explained matters to them and tried to persuade the burghers to be content with their new commandants. It was evident, however, that many were not to be satisfied and that they were not to be expected to work harmoniously together. I therefore decided to let both commandants keep their positions and to let the men follow whichever one they chose, and I took the first opportunity of making an attack on the enemy so as to test the efficiency of these two bodies.

Taking the two commandos with their respective two commandants in an easterly direction to Wit River, we camped there for a few days and scouted for the enemy on the Delagoa Bay Railway, so as to find out the best spot to attack. We had just decided to attack Crocodilpoort Station in the evening of the 1st August, when our scouts reported that the English, who had held the fort at M’pisana’s Stad, between our laager in Wit River and Leydsdorp, were moving in the direction of Komati Poort with a great quantity of captured cattle.

Our first plan was therefore abandoned and I ordered 50 burghers of each commando to attack this column at M’pisana’s fort at once, as they had done far too much harm to be allowed to get away unmolested. They were a group of men called “Steinacker’s Horse,” a corps formed of all the desperadoes and vagabonds to be scraped together from isolated places in the north, including kaffir storekeepers, smugglers, spies, and scoundrels of every description, the whole commanded by a character of the name of ——. Who or what this gentleman was I have never been able to discover, but judging by his work and by the men under him, he must have been a second Musolino. This corps had its headquarters at Komati Poort, under Major Steinacker, to whom was probably entrusted the task of guarding the Portuguese frontier, and he must have been given carte blanche as regards his mode of operation.

From all accounts the primary occupation of this corps appeared to be looting, and the kaffirs attached to it were used for scouting, fighting, and worse. Many families in the northern part of Lydenburg had been attacked in lonely spots, and on one occasion the white men on one of these marauding expeditions had allowed the kaffirs to murder ten defenceless people with their assegais and hatchets, capturing their cattle and other property. In like manner were massacred the relatives of Commandants Lombard, Vermaak, Rudolf and Stoltz, and doubtless many others who were not reported to me. The reader will now understand my anxiety to put some check on these lawless brigands. The instructions to the commando which I had sent out, and which would reach M’pisana’s in two days, were briefly to take the fort and afterwards do as circumstances dictated. If my men failed they would have the desperadoes pursue them on their swift horses, and all the kaffir tribes would conspire against us, so that none would escape on our side. A kaffir was generally understood to be a neutral person in this War, and unless found armed within our lines, with no reasonable excuse for his presence, we generally left him alone. They were, however, largely used as spies against us, keeping to their kraals in the daytime and issuing forth at night to ascertain our position and strength. They also made good guides for the English troops, who often had not the faintest idea of the country in which they were. It must not be forgotten that when a kaffir is given a rifle he at once falls a prey to his brutal instincts, and his only amusement henceforth becomes to kill without distinction of age, colour, or sex. Several hundreds of such natives, led by white men, were roaming about in this district, and all that was captured, plundered or stolen was equally divided among them, 25 per cent. being first deducted for the British Government.

I have indulged in this digression in order to describe another phase with which we had to contend in our struggle for existence. I have reason to believe, however, that the British Commander-in-Chief, for whom I have always had the greatest respect, was not at that time aware of the remarkable character of these operations, carried on as they were in the most remote parts of the country; and there is no doubt that had he been aware of their true character he would have speedily brought these miscreants to justice.

4.5