Editor’s note: The following is excerpted from Hero-Myths and Legends of the British Race, by M.I. Ebbutt (published 1910)

The Roland Legends

CHARLES THE GREAT, King of the Franks, world-famous as Charlemagne, won his undying renown by innumerable victories for France and for the Church. Charles as the head of the Holy Roman Empire and the Pope as the head of the Holy Catholic Church equally dominated the imagination of the mediæval world. Yet in romance Charlemagne’s fame has been eclipsed by that of his illustrious nephew and vassal, Roland, whose crowning glory has sprung from his last conflict and heroic death in the valley of Roncesvalles.

Briefly, the historical facts are these: In A.D. 778 Charles was returning from an expedition into Spain, where the dissensions of the Moorish rulers had offered him the chance of extending his borders while he fought for the Christian faith against the infidel. He had taken Pampeluna, but had been checked before Saragossa, and had not ventured beyond the Ebro; he was now making his way home through the Pyrenees. When the main army had safely traversed the passes, the rear was suddenly attacked by an overwhelming body of mountaineers, Gascons and Basques, who, resenting the violation of their mountain sanctuaries, and longing for plunder, drove the Frankish rearguard into a little valley (now marked by the chapel of Ibagneta and still called Roncesvalles), and there slew every man.

The Historic Basis

The whole romantic legend of Roland has sprung from the simple words in a contemporary chronicle, “In which battle was slain Roland, prefect of the marches of Brittany.”

This same fight of Roncesvalles was the theme of an archaic poem, the “Song of Altobiscar,” written about 1835. In it we hear the exultation of the Basques as they see the knights of France fall beneath their onslaughts. The Basques are on the heights—they hear the trampling of a mighty host which throngs the narrow valley below: its numbers are as countless as the sands of the sea, its movement as resistless as the waves which roll those sands on the shore. Awe fills the bosoms of the mountain tribesmen, but their leader is undaunted. “Let us unite our strong arms!” he cries aloud. “Let us tear our rocks from their beds and hurl them upon the enemy! Let us crush and slay them all!” So said, so done: the rocks roll plunging into the valley, slaying whole troops in their descent. “And what mangled flesh, what broken bones, what seas of blood! Soon of that gallant band not one is left alive; night covers all, the eagles devour the flesh, and the bones whiten in this valley to all eternity!”

A Spanish Version

So runs the “Song of Altobiscar.” But Spain too claims part of the honour of the day of Roncesvalles. True, Roland was in reality slain by Basques, not by Spaniards; but Spain, eager to share the honour, has glorified a national hero, Bernardo del Carpio, who, in the Spanish legend, defeats Roland in single combat and wins the day.

The Italian Orlando

Italy has laid claim to Roland, and in the guise of Orlando, Orlando Furioso, Orlando Innamorato, has made him into a fantastic, chivalrous knight, a hero of many magical adventures.

Roland in French Literature

Noblest of all, however, is the development of the “Roland Saga” in French literature; for, even setting aside much legendary lore and accumulated tradition, the Roland of the old epic is a perfect hero of the early days of feudalism, when chivalry was in its very beginnings, before the cult of the Blessed Virgin Mary added the grace of courtesy to its heroism. Evidently Roland had grown in importance before the “Chanson de Roland” took its present form, for we find the rearguard skirmish magnified into a great battle, which manifestly contains recollections of later Saracen invasions and Gascon revolts. As befits the hero of an epic, Roland is now of royal blood, the nephew of the great emperor, who has himself increased in age and splendour; this heroic Roland can obviously only be overcome by the treachery of one of the Franks themselves, so there appears the traitor Ganelon (a Romance version of a certain Danilo or Nanilo), who is among the Twelve Peers what Judas was among the Apostles; the mighty Saracens, not the insignificant Basques, are now the victors; and the vengeance taken by Charlemagne on the Saracens and on the traitor is boldly added to history, which leaves the disaster unavenged. Thus the bare fact was embroidered over gradually by the historical imagination, aided by patriotism, until a really national hero was evolved out of an obscure Breton count.

The “Chanson de Roland”

The “Song of Roland,” as we now have it, seems to be a late version of an Anglo-Norman poem, made by a certain Turoldus or Thorold; and it must bear a close resemblance to that chant which fired the soldiers of William the Norman at Hastings, when

The “Song of Roland” bears an intimate relation to the development of European thought, and the hero is doubly worth our study as hero and as type of national character. Thus runs the story:

The Story

The Emperor Charles the Great, Carolus Magnus, or Charlemagne, had been for seven years in Spain, and had conquered it from sea to sea, except Saragossa, which, among its lofty mountains, and ruled by its brave king Marsile, had defied his power. Marsile still held to his idols, Mahomet, Apollo, and Termagaunt, dreading in his heart the day when Charles would force him to become a Christian.

The Saracen Council

The Saracen king gathered a council around him, as he reclined on a seat of blue marble in the shade of an orchard, and asked the advice of his wise men.

Blancandrin’s Advice

A wily emir, Blancandrin, of Val-Fonde, was the only man who replied. He was wise in counsel, brave in war, a loyal vassal to his lord.

An Embassy to Charlemagne

Now King Marsile dismissed the council with words of thanks, only retaining near him ten of his most famous barons, chief of whom was Blancandrin; to them he said: “My lords, go to Cordova, where Charles is at this time. Bear olive-branches in your hands, in token of peace, and reconcile me with him. Great shall be your reward if you succeed. Beg Charles to have pity on me, and I will follow him to Aix within a month, will receive the Christian law, and become his vassal in love and loyalty.”

“Sire,” said Blancandrin, “you shall have a good treaty!”

The ten messengers departed, bearing olive-branches in their hands, riding on white mules, with reins of gold and saddles of silver, and came to Charles as he rested after the siege of Cordova, which he had just taken and sacked.

Reception by Charlemagne

Charlemagne was in an orchard with his Twelve Peers and fifteen thousand veteran warriors of France. The messengers from the heathen king reached this orchard and asked for the emperor; their gaze wandered over groups of wise nobles playing at chess, and groups of gay youths fencing, till at last it rested on a throne of solid gold, set under a pine-tree and overshadowed with eglantine. There sat Charles, the king who ruled fair France, with white flowing beard and hoary head, stately of form and majestic of countenance. No need was there of usher to cry: “Here sits Charles the King.”

The ambassadors greeted Charlemagne with all honour, and Blancandrin opened the embassy thus:

“Peace be with you from God the Lord of Glory whom you adore! Thus says the valiant King Marsile: He has been instructed in your faith, the way of salvation, and is willing to be baptized; but you have been too long in our bright Spain, and should return to Aix. There will he follow you and become your vassal, holding the kingdom of Spain at your hand. Gifts have we brought from him to lay at your feet, for he will share his treasures with you!”

He is Perplexed

Charlemagne raised his hands in thanks to God, but then bent his head and remained thinking deeply, for he was a man of prudent mind, cautious and far-seeing, and never spoke on impulse. At last he said proudly: “Ye have spoken fairly, but Marsile is my greatest enemy: how can I trust your words?”

Blancandrin replied: “He will give hostages, twenty of our noblest youths, and my own son will be among them. King Marsile will follow you to the wondrous springs of Aix-la-Chapelle, and on the feast of St. Michael will receive baptism in your court.”

Thus the audience ended. The messengers were feasted in a pavilion raised in the orchard, and the night passed in gaiety and good-fellowship.

He Consults his Twelve Peers

In the early morning Charlemagne arose and heard Mass; then, sitting beneath a pine-tree, he called the Twelve Peers to council. There came the twelve heroes, chief of them Roland and his loyal brother-in-arms Oliver; there came Archbishop Turpin; and, among a thousand loyal Franks, there came Ganelon the traitor. When all were seated in due order Charlemagne began:

“My lords and barons, I have received an embassy of peace from King Marsile, who sends me great gifts and offers, but on condition that I leave Spain and return to Aix. Thither will he follow me, to receive the Faith, become a Christian and my vassal. Is he to be trusted?”

“Let us beware,” cried all the Franks.

Roland Speaks

Roland, ever impetuous, now rose without delay, and spoke: “Fair uncle and sire, it would be madness to trust Marsile. Seven years have we warred in Spain, and many cities have I won for you, but Marsile has ever been treacherous. Once before when he sent messengers with olive-branches you and the French foolishly believed him, and he beheaded the two counts who were your ambassadors to him. Fight Marsile to the end, besiege and sack Saragossa, and avenge those who perished by his treachery.”

Ganelon Objects

Charlemagne looked out gloomily from under his heavy brows, he twisted his moustache and pulled his long white beard, but said nothing, and all the Franks remained silent, except Ganelon, whose hostility to Roland showed clearly in his words:

“Sire, blind credulity were wrong and foolish, but follow up your own advantage. When Marsile offers to become your vassal, to hold Spain at your hand and to take your faith, any man who urges you to reject such terms cares little for our death! Let pride no longer be your counsellor, but hear the voice of wisdom.”

The aged Duke Naimes, the Nestor of the army, spoke next, supporting Ganelon: “Sire, the advice of Count Ganelon is wise, if wisely followed. Marsile lies at your mercy; he has lost all, and only begs for pity. It would be a sin to press this cruel war, since he offers full guarantee by his hostages. You need only send one of your barons to arrange the terms of peace.”

This advice pleased the whole assembly, and a murmur was heard: “The Duke has spoken well.”

“Who Shall Go to Saragossa?”

Roland Suggests Ganelon

“Knights of France,” quoth Charlemagne, “choose me now one of your number to do my errand to Marsile, and to defend my honour valiantly, if need be.”

“Ah,” said Roland, “then it must be Ganelon, my stepfather; for whether he goes or stays, you have none better than he!”

This suggestion satisfied all the assembly, and they cried: “Ganelon will acquit himself right manfully. If it please the King, he is the right man to go.”

Charlemagne thought for a moment, and then, raising his head, beckoned to Ganelon. “Come hither, Ganelon,” he said, “and receive this glove and staff, which the voice of all the Franks gives to thee.”

Ganelon is Angry

“No,” replied Ganelon, wrathfully. “This is the work of Roland, and I will never forgive him, nor his friends, Oliver and the other Peers. Here, in your presence, I bid them defiance!”

“Your anger is too great,” said Charlemagne; “you will go, since it is my will also.”

“Yes, I shall go, but I shall perish as did your two former ambassadors. Sire, forget not that your sister is my wife, and that Baldwin, my son, will be a valiant champion if he lives. I leave to him my lands and fiefs. Sire, guard him well, for I shall see him no more.”

“Your heart is too tender,” said Charlemagne. “You must go, since such is my command.”

He Threatens Roland

Ganelon, in rage and anguish, glared round the council, and his face drew all eyes, so fiercely he looked at Roland.

“Madman,” said he, “all men know that I am thy stepfather, and for this cause thou hast sent me to Marsile, that I may perish! But if I return I will be revenged on thee.”

“Madness and pride,” Roland retorted, “have no terrors for me; but this embassy demands a prudent man not an angry fool: if Charles consents, I will do his errand for thee.”

“Thou shalt not. Thou art not my vassal, to do my work, and Charles, my lord, has given me his commands. I go to Saragossa; but there will I find some way to vent my anger.”

Now Roland began to laugh, so wild did his stepfather’s threats seem, and the laughter stung Ganelon to madness. “I hate you,” he cried to Roland; “you have brought this unjust choice on me.” Then, turning to the emperor: “Mighty lord, behold me ready to fulfil your commands.”

But is Sent

“Fair Lord Ganelon,” spoke Charlemagne, “bear this message to Marsile. He must become my vassal and receive holy baptism. Half of Spain shall be his fief; the other half is for Count Roland. If Marsile does not accept these terms I will besiege Saragossa, capture the town, and lead Marsile prisoner to Aix, where he shall die in shame and torment. Take this letter, sealed with my seal, and deliver it into the king’s own right hand.”

Thereupon Charlemagne held out his right-hand glove to Ganelon, who would fain have refused it. So reluctant was he to grasp it that the glove fell to the ground. “Ah, God!” cried the Franks, “what an evil omen! What woes will come to us from this embassy!” “You shall hear full tidings,” quoth Ganelon. “Now, sire, dismiss me, for I have no time to lose.” Very solemnly Charlemagne raised his hand and made the sign of the Cross over Ganelon, and gave him his blessing, saying, “Go, for the honour of Jesus Christ, and for your Emperor.” So Ganelon took his leave, and returned to his lodging, where he prepared for his journey, and bade farewell to the weeping retainers whom he left behind, though they begged to accompany him. “God forbid,” cried he, “that so many brave knights should die! Rather will I die alone. You, sirs, return to our fair France, greet well my wife, guard my son Baldwin, and defend his fief!”

He Plots with Marsile’s Messengers

Then Ganelon rode away, and shortly overtook the ambassadors of the Moorish king, for Blancandrin had delayed their journey to accompany him, and the two envoys began a crafty conversation, for both were wary and skilful, and each was trying to read the other’s mind. The wily Saracen began:

To Betray Roland

The bitterness in Ganelon’s tone at once struck: Blancandrin, who cast a glance at him and saw the Frankish envoy trembling with rage. He suddenly addressed Ganelon in whispered tones: “Hast thou aught against the nephew of Charles? Wouldst thou have revenge on Roland? Deliver him to us, and King Marsile will share with thee all his treasures.” Ganelon was at first horrified, and refused to hear more, but so well did Blancandrin argue and so skilfully did he lay his snare that before they reached Saragossa and came to the presence of King Marsile it was agreed that Roland should be destroyed by their means.

Ganelon with the Saracens

Blancandrin and his fellow ambassadors conducted Ganelon into the presence of the Saracen king, and announced Charlemagne’s peaceable reception of their message and the coming of his envoy. “Let him speak: we listen,” said Marsile.

Ganelon then began artfully: “Peace be to you in the name of the Lord of Glory whom we adore! This is the message of King Charles: You shall receive the Holy Christian Faith, and Charles will graciously grant you one-half of Spain as a fief; the other half he intends for his nephew Roland (and a haughty partner you will find him!). If you refuse he will take Saragossa, lead you captive to Aix, and give you there to a shameful death.”

Marsile’s Anger

Marsile’s anger was so great at this insulting message that he sprang to his feet, and would have slain Ganelon with his gold-adorned javelin; but he, seeing this, half drew his sword, saying:

The Saracen Council

However, strife was averted, and Ganelon received praise from all for his bold bearing and valiant defiance of his king’s enemy. When quiet was restored he repeated his message and delivered the emperor’s letter, which was found to contain a demand that the caliph, Marsile’s uncle, should be sent, a prisoner, to Charles, in atonement for the two ambassadors foully slain before. The indignation of the Saracen nobles was intense, and Ganelon was in imminent danger, but, setting his back against a pine-tree, he prepared to defend himself to the last. Again the quarrel was stayed, and Marsile, taking his most trusted leaders, withdrew to a secret council, whither, soon, Blancandrin led Ganelon. Here Marsile excused his former rage, and, in reparation, offered Ganelon a superb robe of marten’s fur, which was accepted; and then began the tempting of the traitor. First demanding a pledge of secrecy, Marsile pitied Charlemagne, so aged and so weary with rule. Ganelon praised his emperor’s prowess and vast power. Marsile repeated his words of pity, and Ganelon replied that as long as Roland and the Twelve Peers lived Charlemagne needed no man’s pity and feared no man’s power; his Franks, also, were the best living warriors. Marsile declared proudly that he could bring four hundred thousand men against Charlemagne’s twenty thousand French; but Ganelon dissuaded him from any such expedition.

Ganelon Plans Treachery

Welcomed by Marsile

Marsile was overjoyed at the treacherous advice and embraced and richly rewarded the felon knight. The death of Roland and the Peers was solemnly sworn between them, by Marsile on the book of the Law of Mahomet, by Ganelon on the sacred relics in the pommel of his sword. Then, repeating the compact between them, and warning Ganelon against treason to his friends, Marsile dismissed the treacherous envoy who hastened to return and put his scheme into execution.

Ganelon Returns to Charles

In the meantime Charles had retired as far as Valtierra, on his way to France, and there Ganelon found him, and delivered the tribute, the keys of Saragossa, and a false message excusing the absence of the caliph. He had, so Marsile said, put to sea with three hundred thousand warriors who would not renounce their faith, and all had been drowned in a tempest, not four leagues from land. Marsile would obey King Charles’s commands in all other respects. “Thank God!” cried Charlemagne. “Ganelon, you have done well, and shall be well rewarded!”

The French Camp. Charles Dreams

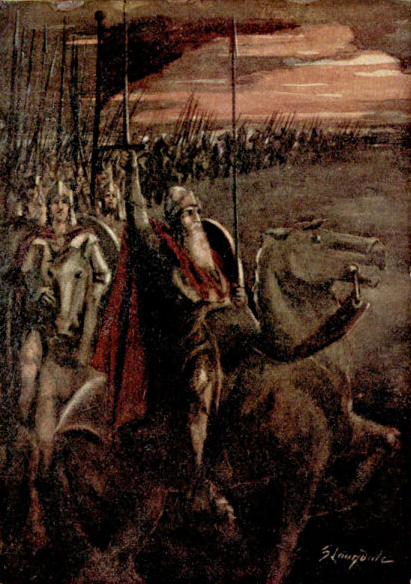

Now the whole Frankish army marched towards the Pyrenees, and, as evening fell, found themselves among the mountains, where Roland planted his banner on the topmost summit, clear against the sky, and the army encamped for the night; but the whole Saracen host had also marched and encamped in a wood not far from the Franks. Meanwhile, as Charlemagne slept he had dreams of evil omen. Ganelon, in his dreams, seized the imperial spear of tough ash-wood, and broke it, so that the splinters flew far and wide. In another dream he saw himself at Aix attacked by a leopard and a bear, which tore off his right arm; a greyhound came to his aid but he knew not the end of the fray, and slept unhappily.

A Morning Council

When morning light shone, and the army was ready to march, the clarions of the host sounded gaily, and Charlemagne called his barons around him.

When Roland heard that he was to command the rearguard he knew not whether to be pleased or not. At first he thanked Ganelon for naming him. “Thanks, fair stepfather, for sending me to the post of danger. King Charles shall lose no man nor horse through my neglect.” But when Ganelon replied sneeringly, “You speak the truth, as I know right well,” Roland’s gratitude turned to bitter anger, and he reproached the villain. “Ah, wretch! disloyal traitor! thou thinkest perchance that I, like thee, shall basely drop the glove, but thou shalt see! Sir King, give me your bow. I will not let my badge of office fall, as thou didst, Ganelon, at Cordova. No evil omen shall assail the host through me.”

Roland for the Rearguard

Charlemagne was very loath to grant his request, but on the advice of Duke Naimes, most prudent of counsellors, he gave to Roland his bow, and offered to leave with him half the army. To this the champion would not agree, but would only have twenty thousand Franks from fair France. Roland clad himself in his shining armour, laced on his lordly helmet, girt himself with his famous sword Durendala, and hung round his neck his flower-painted shield; he mounted his good steed Veillantif, and took in hand his bright lance with the white pennon and golden fringe; then, looking like the Archangel St. Michael, he rode forward, and easy it was to see how all the Franks loved him and would follow where he led. Beside him rode the famous Peers of France, Oliver the bold and courteous, the saintly Archbishop Turpin, and Count Gautier, Roland’s loyal vassal. They chose carefully the twenty thousand French for the rearguard, and Roland sent Gautier with one thousand of their number to search the mountains. Alas! they never returned, for King Almaris, a Saracen chief, met and slew them all among the hills; and only Gautier, sorely wounded and bleeding to death, returned to Roland in the final struggle.

Charlemagne spoke a mournful “Farewell” to his nephew and the rearguard, and the mighty army began to traverse the gloomy ravine through the dark masses of rocks, and to emerge on the other side of the Pyrenees. All wept, most for joy to set eyes on that dear land of fair France, which for seven years they had not seen; but Charles, with a sad foreboding of disaster, hid his eyes beneath his cloak and wept in silence.

Charles is Sad

“What grief weighs on your mind, sire?” asked the wise Duke Naimes, riding up beside Charlemagne.

“I mourn for my nephew. Last night in a vision I saw Ganelon break my trusty lance—this Ganelon who has sent Roland to the rear. And now I have left Roland in a foreign land, and, O God! if I lose him I shall never find his equal!” And the emperor rode on in silence, seeing naught but his own sad foreboding visions.

The Saracen Pursuit

Meanwhile King Marsile, with his countless Saracens, had pursued so quickly that the van of the heathen army soon saw waving the banners of the Frankish rear. Then as they halted before the strife began, one by one the nobles of Saragossa, the champions of the Moors, advanced and claimed the right to measure themselves against the Twelve Peers of France. Marsile’s nephew received the royal glove as chief champion, and eleven Saracen chiefs took a vow to slay Roland and spread the faith of Mahomet.

“Death to the rearguard! Roland shall die! Death to the Peers! Woe to France and Charlemagne! We will bring the Emperor to your feet! You shall sleep at St. Denis! Down with fair France!” Such were their confident cries as they armed for the conflict; and on their side no less eager were the Franks.

“Fair Sir Comrade,” said Oliver to Roland, “methinks we shall have a fray with the heathen.”

“God grant it,” returned Roland. “Our duty is to hold this pass for our king. A vassal must endure for his lord grief and pain, heat and cold, torment and death; and a knight’s duty is to strike mighty blows, that men may sing of him, in time to come, no evil songs. Never shall such be sung of me.”

Oliver Descries the Saracens

Hearing a great tumult, Oliver ascended a hill and looked towards Spain, where he perceived the great pagan army, like a gleaming sea, with shining hauberks and helms flashing in the sun. “Alas! we are betrayed! This treason is plotted by Ganelon, who put us in the rear,” he cried. “Say no more,” said Roland; “blame him not in this: he is my stepfather.”

Now Oliver alone had seen the might of the pagan array, and he was appalled by the countless multitudes of the heathens. He descended from the hill and appealed to Roland.

Roland will not Blow his Horn

Roland was a valiant hero, but Oliver had prudence as well as valour, and his advice was that of a good and careful general. Now he spoke reproachfully.

It is Too Late

“Ah, Roland, if you had sounded your magic horn the king would soon be here, and we should not perish! Now look to the heights and to the mountain passes: see those who surround us. None of us will see the light of another day!”

“Speak not so foolishly,” retorted Roland. “Accursed be all cowards, say I.” Then, softening his tone a little, he continued: “Friend and comrade, say no more. The emperor has entrusted to us twenty thousand Frenchmen, and not a coward among them. Lay on with thy lance, Oliver, and I will strike with Durendala. If I die men shall say: ‘This was the sword of a noble vassal.’”

Turpin Blesses the Knights

Then spoke the brave and saintly Archbishop Turpin. Spurring his horse, he rode, a gallant figure, to the summit of a hill, whence he called aloud to the Frankish knights:

The Frankish knights, dismounting, knelt before Turpin, who blessed and absolved them all, bidding them, as penance, to strike hard against the heathen.

Then Roland called his brother-in-arms, the brave and courteous Oliver, and said: “Fair brother, I know now that Ganelon has betrayed us for reward and Marsile has bought us; but the payment shall be made with our swords, and Charlemagne will terribly avenge us.”

“Montjoie! Montjoie!”

While the two armies yet stood face to face in battle array Oliver replied: “What good is it to speak? You would not sound your horn, and Charles cannot help us; he is not to blame. Barons and lords, ride on and yield not. In God’s name fight and slay, and remember the war-cry of our Emperor.” And at the words the war-cry of “Montjoie! Montjoie!” burst from the whole army as they spurred against the advancing heathen host.

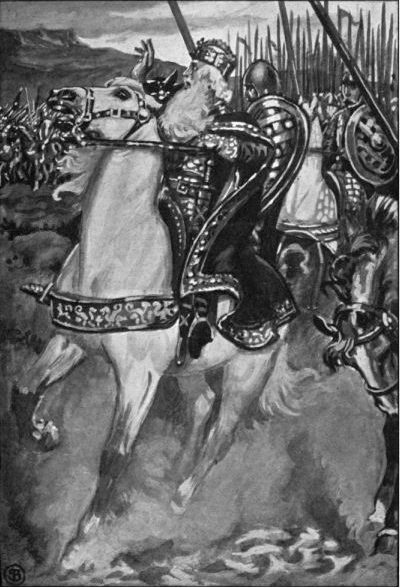

The Fray

Great was the fray that day, deadly was the combat, as the Moors and Franks crashed together, shouting their cries, invoking their gods or saints, wielding with utmost courage sword, lance, javelin, scimitar, or dagger. Blades flashed, lances were splintered, helms were cloven in that terrible fight of heroes. Each of the Twelve Peers did mighty feats of arms. Roland himself slew the nephew of King Marsile, who had promised to bring Roland’s head to his uncle’s feet, and bitter were the words that Roland hurled at the lifeless body of his foe, who had but just before boasted that Charlemagne should lose his right hand. Oliver slew the heathen king’s brother, and one by one the Twelve Peers proved their mettle on the twelve champions of King Marsile, and left them dead or mortally wounded on the field. Wherever the battle was fiercest and the danger greatest, where help was most needed, there Roland spurred to the rescue, swinging Durendala, and, falling on the heathen like a thunderbolt of war, turned the tide of battle again and yet again.

Like the red god Mars he rode through the battle; and as he went he met Oliver, with the truncheon or a spear in his grasp.

The Saracens Perish

Thus the battle continued, most valiantly contested by both sides, and the Saracens died by hundreds and thousands, till all their host lay dead but one man, who fled wounded, leaving the Frenchmen masters of the field, but in sorry plight—broken were their swords and lances, rent their hauberks, torn and blood-stained their gay banners and pennons, and many, many of their brave comrades lay lifeless. Sadly they looked round on the heaps of corpses, and their minds were filled with grief as they thought of their companions, of fair France which they should see no more, and of their emperor who even now awaited them while they fought and died for him. Yet they were not discouraged; loudly their cry re-echoed, “Montjoie! Montjoie!” as Roland cheered them on, and Turpin called aloud: “Our men are heroes; no king under heaven has better. It is written in the Chronicles of France that in that great land it is our king’s right to have valiant soldiers.”

A Second Saracen Army

While they sought in tears the bodies of their friends, the main army of the Saracens, under King Marsile in person, came upon them; for the one fugitive who had escaped had urged Marsile to attack again at once, while the Franks were still weary. The advice seemed good to Marsile, and he advanced at the head of a hundred thousand men, whom he now hurled against the French in columns of fifty thousand at a time; and they came on right valiantly, with clarions sounding and trumpets blowing.

And the battle raged anew, with all the odds against the small handful of French, who knew they were doomed, and fought as though they were “fey.”

Gloomy Portents

Meanwhile the whole course of nature was disturbed. In France there were tempests of wind and thunder, rain and hail; thunderbolts fell everywhere, and the earth shook exceedingly. From Mont St. Michel to Cologne, from Besançon to Wissant, not one town could show its walls uninjured, not one village its houses unshaken. A terrible darkness spread over all the land, only broken when the heavens split asunder with the lightning-flash. Men whispered in terror: “Behold the end of the world! Behold the great Day of Doom!” Alas! they knew not the truth: it was the great mourning for the death of Roland.

Many French Knights Fall

In this second battle the French champions were weary, and before long they began to fall before the valour of the newly arrived Saracen nobles. First died Engelier the Gascon, mortally wounded by the lance of that Saracen who swore brotherhood to Ganelon; next Samson, and the noble Duke Anseis. These three were well avenged by Roland and Oliver and Turpin. Then in quick succession died Gerin and Gerier and other valiant Peers at the hands of Grandoigne, until his death-dealing career was cut short by Durendala. Another desperate single combat was won by Turpin, who slew a heathen emir “as black as molten pitch.”

The Second Army Defeated

Finally this second host of the heathens gave way and fled, begging Marsile to come and succour them; but now of the victorious French there were but sixty valiant champions left alive, including Roland, Oliver, and the fiery prelate Turpin

A Third Appears

Now the third host of the pagans began to roll forward upon the dauntless little band, and in the short breathing-space before the Saracens again attacked them Roland cried aloud to Oliver:

Roland Willing to Blow his Horn

Oliver Objects. They Quarrel

Turpin Mediates

Archbishop Turpin heard the dispute, and strove to calm the angry heroes. “Brave knights, be not so enraged. The horn will not save the lives of these gallant dead, but it will be better to sound it, that Charles, our lord and emperor, may return, may avenge our death and weep over our corpses, may bear them to fair France, and bury them in the sanctuary, where the wild beasts shall not devour them.” “That is well said,” quoth Roland and Oliver.

The Horn is Blown

Then at last Roland put the carved ivory horn, the magic Olifant, to his lips, and blew so loudly that the sound echoed thirty leagues away. “Hark! our men are in combat!” cried Charlemagne; but Ganelon retorted: “Had any but the king said it, that had been a lie.”

A second time Roland blew his horn, so violently and with such anguish that the veins of his temples burst, and the blood flowed from his brow and from his mouth. Charlemagne, pausing, heard it again, and said: “That is Roland’s horn; he would not sound it were there no battle.” But Ganelon said mockingly: “There is no battle, for Roland is too proud to sound his horn in danger. Besides, who would dare to attack Roland, the strong, the valiant, great and wonderful Roland? No man. He is doubtless hunting, and laughing with the Peers. Your words, my liege, do but show how old and weak and doting you are. Ride on, sire; the open country lies far before you.”

Ganelon Arrested

Then Charlemagne called aloud: “Hither, my men. Take this traitor Ganelon and keep him safe till my return.” And the kitchen folk seized the felon knight, chained him by the neck, and beat him; then, binding him hand and foot, they flung him on a sorry nag, to be borne with them till Charles should demand him at their hands again.

Charles Returns

With all speed the whole army retraced their steps, turning their faces to Spain, and saying: “Ah, if we could find Roland alive what blows we would strike for him!” Alas! it was too late! Too late!

How lofty are the peaks, how vast and shadowy the mountains! How dim and gloomy the passes, how deep the valleys! How swift the rushing torrents! Yet with headlong speed the Frankish army hastens back, with trumpets sounding in token of approaching help, all praying God to preserve Roland till they come. Alas! they cannot reach him in time! Too late. Too late!

Roland Weeps for his Comrades

Now Roland cast his gaze around on hill and valley, and saw his noble vassals and comrades lie dead. As a noble knight he wept for them, saying:

He Fights Desperately

So saying, he rushed into the battle, slew the only son of King Marsile, and drove the heathen before him as the hounds drive the deer. Turpin saw and applauded. “So should a good knight do, wearing good armour and riding a good steed. He must deal good strong strokes in battle, or he is not worth a groat. Let a coward be a monk in some cloister and pray for the sins of us fighters.”

Marsile in wrath attacked the slayer of his son, but in vain; Roland struck off his right hand, and Marsile fled back mortally wounded to Saragossa, while his main host, seized with panic, left the field to Roland. However, the caliph, Marsile’s uncle, rallied the ranks, and, with fifty thousand Saracens, once more came against the little troop of Champions of the Cross, the three poor survivors of the rearguard.

Roland cried aloud: “Now shall we be martyrs for our faith. Fight boldly, lords, for life or death! Sell yourselves dearly! Let not fair France be dishonoured in her sons. When the Emperor sees us dead with our slain foes around us he will bless our valour.”

Oliver Falls

The pagans were emboldened by the sight of the three alone, and the caliph, rushing at Oliver, pierced him from behind with his lance. But though mortally wounded Oliver retained strength enough to slay the caliph, and to cry aloud: “Roland! Roland! Aid me!” then he rushed on the heathen army, doing heroic deeds and shouting “Montjoie! Montjoie!” while the blood ran from his wound and stained the earth blood-red. At this woeful sight Roland swooned with grief, and Oliver, faint from loss of blood, and with eyes dimmed by fast-coming death, distinguished not the face of his dear friend; he saw only a vague figure drawing near, and, mistaking it for an enemy, raised his sword Hauteclaire and gave Roland one last terrible blow, which clove the helmet, but harmed not the head. The blow roused Roland from his swoon, and, gazing tenderly at Oliver, he gently asked him:

And Dies

Now Oliver felt the pains of death come upon him. Both sight and hearing were gone, his colour fled, and, dismounting, he lay upon the earth; there, humbly confessing his sins, he begged God to grant him rest in Paradise, to bless his lord Charlemagne and the fair land of France, and to keep above all men his comrade Roland, his best-loved brother-in-arms. This ended, he fell back, his heart failed, his head drooped low, and Oliver the brave and courteous knight lay dead on the blood-stained earth, with his face turned to the east. Roland lamented him in gentle words: “Comrade, alas for thy valour! Many days and years have we been comrades: no ill didst thou to me, nor I to thee: now thou art dead, ’tis pity that I live!”

Turpin is Mortally Wounded. The Horn Again

Turpin and Roland now stood together for a time and were joined by the brave Count Gautier, whose thousand men had been slain, and he himself grievously wounded; he now came, like a loyal vassal, to die with his lord Roland, and was slain in the first discharge of arrows which the Saracens shot. Taught by experience, the pagans kept their distance, and wounded Turpin with four lances, while they stood some yards away from the heroes. But when Turpin felt himself mortally wounded he plunged into the throng of the heathen, killing four hundred before he fell, and Roland fought on with broken armour, and with ever-bleeding head, till in a pause of the deadly strife he took his horn and again sent forth a feeble dying blast.

Charles Answers the Horn

Charlemagne heard it, and was filled with anguish. “Lords, all goes ill: I know by the sound of Roland’s horn he has not long to live! Ride on faster, and let all our trumpets sound, in token of our approach.” Then sixty thousand trumpets sounded, so that mountains echoed it and valleys replied, and the heathen heard it and trembled. “It is Charlemagne! Charles is coming!” they cried. “If Roland lives till he comes the war will begin again, and our bright Spain is lost.” Thereupon four hundred banded together to slay Roland; but he rushed upon them, mounted on his good steed Veillantif, and the valiant pagans fled. But while Roland dismounted to tend the dying archbishop they returned and cast darts from afar, slaying Veillantif, the faithful war-horse, and piercing the hero’s armour. Still nearer and nearer sounded the clarions of Charlemagne’s army in the defiles, and the Saracen host fled for ever, leaving Roland alone, on foot, expiring, amid the dying and the dead.

Turpin Blesses the Dead

Roland made his way to Turpin, unlaced his golden helmet, took off his hauberk, tore his own tunic to bind up his grievous wounds, and then gently raising the prelate, carried him to the fresh green grass, where he most tenderly laid him down.

With great pain and many delays Roland traversed the field of slaughter, looking in the faces of the dead, till he had found and brought to Turpin’s feet the bodies of the eleven Peers, last of all Oliver, his own dear friend and brother, and Turpin blessed and absolved them all. Now Roland’s grief was so deep and his weakness so great that he swooned where he stood, and the archbishop saw him fall and heard his cry of pain. Slowly and painfully Turpin struggled to his feet, and, bending over Roland, took Olifant, the curved ivory horn; inch by inch the dying archbishop tottered towards a little mountain stream, that the few drops he could carry might revive Roland.

He Dies

However, his weakness overcame him before he reached the water, and he fell forward dying. Feebly he made his confession, painfully he joined his hands in prayer, and as he prayed his spirit fled. Turpin, the faithful champion of the Cross, in teaching and in battle, died in the service of Charlemagne. May God have mercy on his soul!

When Roland awoke from his swoon he looked for Turpin, and found him dead, and, seeing Olifant, he guessed what the archbishop’s aim had been, and wept for pity. Crossing the fair white hands over Turpin’s breast, he sadly prayed:

Roland’s Last Fight

Now death was very near to Roland, and he felt it coming upon him while he yet prayed and commended himself to his guardian angel Gabriel. Taking in one hand Olifant, and in the other his good sword Durendala, Roland climbed a little hill, one bowshot within the realm of Spain. There under two pine-trees he found four marble steps, and as he was about to climb them, fell swooning on the grass very near his end. A lurking Saracen, who had feigned death, stole from his covert, and, calling aloud, “Charles’s nephew is vanquished! I will bear his sword back to Arabia,” seized Durendala as it lay in Roland’s dying clasp. The attempt roused Roland, and he opened his eyes, saying, “Thou art not of us,” then struck such a blow with Olifant on the helm of the heathen thief that he fell dead before his intended victim.

He Tries to Break his Sword

Pale, bleeding, dying, Roland struggled to his feet, bent on saving his good blade from the defilement of heathen hands. He grasped Durendala, and the brown marble before him split beneath his mighty blows; but the good sword stood firm, the steel grated but did not break, and Roland lamented aloud that his famous sword must now become the weapon of a lesser man. Again Roland smote with Durendala, and clove the block of sardonyx, but the good steel only grated and did not break, and the hero bewailed himself aloud, saying, “Alas! my good Durendala, how bright and pure thou art! How thou flamest in the sunbeams, as when the angel brought thee! How many lands hast thou conquered for Charles my King, how many champions slain, how many heathen converted! Must I now leave thee to the pagans? May God spare fair France this shame!” A third time Roland raised the sword and struck a rock of blue marble, which split asunder, but the steel only grated—it would not break; and the hero knew that he could do no more.

His Last Prayer

Then he flung himself on the ground under a pine-tree with his face to the earth, his sword and Olifant beneath him, his face to the foe, that Charlemagne and the Franks might see when they came that he died victorious. He made his confession, prayed for mercy, and offered to Heaven his glove, in token of submission for all his sins. “Mea culpa! O God! I pray for pardon for all my sins, both great and small, that I have sinned from my birth until this day.” So he held up towards Heaven his right-hand glove, and the angels of God descended around him. Again Roland prayed:

He Dies

Again he held up to Heaven his glove, and St. Gabriel received it; then, with head bowed and hands clasped, the hero died, and the waiting cherubim, St. Raphael, St. Michael, and St. Gabriel, bore his soul to Paradise.

So died Roland and the Peers of France.

Charles Arrives

Soon after Roland’s heroic spirit had passed away the emperor came galloping out of the mountains into the valley of Roncesvalles, where not a foot of ground was without its burden of death.

Loudly he called: “Fair nephew, where art thou? Where is the archbishop? And Count Oliver? Where are the Peers?”

Alas! of what avail was it to call? No man replied, for all were dead; and Charlemagne wrung his hands, and tore his beard and wept, and his army bewailed their slain comrades, and all men thought of vengeance. Truly a fearful vengeance did Charles take, in that terrible battle which he fought the next day against the Emir of Babylon, come from oversea to help his vassal Marsile, when the sun stood still in heaven that the Christians might be avenged on their enemies; in the capture of Saragossa and the death of Marsile, who, already mortally wounded, turned his face to the wall and died when he heard of the defeat of the emir; but when vengeance was taken on the open enemy Charlemagne thought of mourning, and returned to Roncesvalles to seek the body of his beloved nephew.

The emperor knew well that Roland would be found before his men, with his face to the foe. Thus he advanced a bowshot from his companions and climbed a little hill, there found the little flowery meadow stained red with the blood of his barons, and there at the summit, under the trees, lay the body of Roland on the green grass. The broken blocks of marble bore traces of the hero’s dying efforts, and Charlemagne raised Roland, and, clasping the hero in his arms, lamented over him.

His Lament

The Dead Buried

The French army buried the dead with all honour, where they had fallen, except the bodies of Roland, Oliver, and Turpin, which were carried to Blaye, and interred in the great cathedral there; and then Charlemagne returned to Aix.

Aude the Fair

As Charles the Great entered his palace a beauteous maiden met him, Aude the Fair, the sister of Oliver and betrothed bride of Roland. She asked eagerly:

“Where is Roland the mighty captain, who swore to take me for his bride?”

“Alas! dear sister and friend,” said Charlemagne, weeping and tearing his long white beard, “thou askest tidings of the dead. But I will replace him: thou shalt have Louis, my son, Count of the Marches.”

“These words are strange,” exclaimed Aude the Fair. “God and all His saints and angels forbid that I should live when Roland my love is dead.” Thereupon she lost her colour and fell at the emperor’s feet; he thought her fainting, but she was dead. God have mercy on her soul!

The Traitor Put to Death

Too long it would be to tell of the trial of Ganelon the traitor. Suffice it that he was torn asunder by wild horses, and his name remains in France a byword for all disloyalty and treachery.

5

Just terrific.

It’s time Ganelon came back into use as a byword for disloyalty and treachery.

4.5