Editor’s Note: We are happy to offer another gem from our buddy, Rolf. You should already know him as the author of the great novel, The Stars Came Back. Here, he talk about shooting – and shooting effectively.

Precision shooting means different things to different people. To a deer hunter it might mean an eight-inch group at 200 yards – “minute of deer” for a reasonable chest-cavity shot. To a competition pistol shooter, it might mean 1”x3” eye-slot at ten yards (and doing it quickly). Many default to MOA (minute of angle), about one inch at 100 yards (technically, 1.047”) because that’s what the pros talk about. The ten-ring on a thousand-yard target at Camp Perry is 20” across (about 2 MOA). For someone attending a fun shoot like Boomershoot, the explosive targets are 4” at 375 yards, and a mix of 4- and 7-inch targets from 600 to 700 yards.

Precision shooting, regardless of how you define it, requires practice. Pull out your calendar. If you don’t have any range-time scheduled, take a moment to schedule some. Send an email to invite a friend, too.

I’ll wait.

Done? OK, then.

Scoring for a competition is points, or points divided by time. For a deer hunter, “scoring” is meat right there, short track, long track, clean miss, and the worst possible negative score: gut shot and got away. At Boomershoot, precision is binary: boom or no boom (alternately, smile/no-smile).

Old eyes and a limited budget will have a much lower standard than younger eyes or a larger budget might consider acceptable. Indoor, close range home-defense puts a premium on speed, target selection (and never, ever, hitting a “no-shoot” target), and aggressive follow-through over tight groups; minute-of-goblin is sufficient. Meat hunters put a premium on middle-distance under any and all shooting conditions, even unsupported, hunched over, off-hand at a weird angle on a hillside, while standing on a log with strange shadows with gusty winds at an unknown distance (been there, done that, ate the venison). Long range competitive target shooters might spend more on glass and do-dads than a casual hunter spends on ammo in his whole life.

Which is “correct?”

They all are… or none are. It depends.

You need to realistically assess what YOUR situation, needs, budget, physical capabilities, family, and available training opportunities are. But one thing that you must not lose sight of, if you’ll pardon the pun: you are likely the weakest link in your gun’s ability to put a bullet where you want it. Most modern arms have a mechanical accuracy greater than 95% of the population are capable of shooting. You need to expect to practice what you actually need to do: there are few shooting benches in the field with deer set up 100 yards away during deer season.

For the purposes of this essay, I’ll be primarily talking about rifle shooting, somewhere in the Venn diagram overlap between sniper, hunter, rural home defense, and casual mid-distance target shooter.

Define your needs (not mere wants), budget, time-frame, limitations, and your current armory. Got 39 guns and no training budget? Sell a few. Got nothing to shoot but a healthy bank account? Buy a basic pistol and an inexpensive rifle (both in a common and inexpensive caliber, like 9mm and .223, or 22 LR) and hit the range with an experienced buddy or trainer to put a few cases downrange and learn enough to figure out what is the “best” one for your situation; it may not be what you think it will be.

[anecdote: I once took a mousy, middle-aged woman who had never shot before to the range with a bag of guns so see what suited her. After many rounds, she decided the Glock 10mm and the full power .357 mag loads in a long-barreled GP100 were the best options. “Duh heck?!” I thought. Oh, yeah, she’s a massage therapist: very strong hands and arms. She was certain. Good groups, big smile, totally comfortable with them. She said they felt “substantial,” and gave her confidence they’d be able to do the job of dropping a local meth-head. Looking at her hand-sized group from 15 yards, I couldn’t really argue.]

Try a few before you buy.

So, you made it this far.

When is your scheduled range-time? No? Seriously? Schedule it.

Got it? For real? Good. Pop-quiz later.

Can you take your spouse or children with you? Few things make younger kids think their pop is awesome, especially boys, than knowing he can nail a target like a boss. Few things make a wife feel as safe as knowing that her husband is able to protect her and the family competently. Few things give you the motivation to up your game then having your child out-shoot you for the first time; it will also be one of the proudest moments of your life. At the very least, go shooting with a friend, and either coach/spot for one another, or make it a friendly completion.

Can you take your spouse or children with you? Few things make younger kids think their pop is awesome, especially boys, than knowing he can nail a target like a boss. Few things make a wife feel as safe as knowing that her husband is able to protect her and the family competently. Few things give you the motivation to up your game then having your child out-shoot you for the first time; it will also be one of the proudest moments of your life. At the very least, go shooting with a friend, and either coach/spot for one another, or make it a friendly completion.

OK, so you’ve budgeted the time.

How much ammo have you budgeted? (Budget more).

How deliberate can you be?

Do you take notes?

Do you have records you can check to see how you did last time?

Do you have a goal for improvement?

Do you know what your guns are capable of?

Are any of your guns capable of achieving what you set for a goal?

Do you have a steady hand when shooting unsupported, or are your groups minute-of-barn-door at twenty paces because you are quitting coffee, cola, and cigarettes the same week?

Do you know what your biggest strength is?

What’s your most crippling weakness with regard to accuracy?

Best resources available to you for training?

If you don’t know these things for certain, take a minute and think about them, then write them down. Be honest with yourself. But also be pragmatic and realistic. If you “need” to shoot MOA at 200 yards, and all you have is a 1948 Russian SKS with a plywood stock your cousin made, you are going to have to change your goal or your gun. If you need fast minute-of-goblin-head at hallway length distance, your rifle will do fine. If you really do have a real requirement to spank a golf ball sized target at 158 yards, you’re going to have to upgrade your hardware.

Look at the list – what do you have most control over, and what is the most limiting? Prioritize your list as to what you can/should focus on.

Some practice is better than none, but bad instruction can be worse than no instruction. Expect to try out several different instructors, talk to other shooters you respect. Ask at the range if you don’t know any yourself. Find a teacher who will try to understand your goals and help you get there, or has a class that meets your immediate needs.

[Anecdote: look for a teacher who has students that are well-known; they are more likely to know what they are doing that someone that is only a good shooter themselves.]

A good rule of thumb when doing deliberate training (slow, careful, thoughtful) for accuracy is that you’ll want a couple of hours and a hundred rounds per range session. Yes, I know your AR has a cyclic rate of 550/rounds minute. You’re trying for some degree of precision and improvement, not a trophy for the hottest barrel.

[Anecdote: yes, you can cook bacon on the suppressor with foil, string, and four 30-round mags. However, you are unlikely to improve your accuracy much when doing so.]

So you get to the range with a friend, and he’s set up to spot over your shoulder. He can look for trace and call the impact. He can also help call the wind. You need to think about each shot. What went right, what went wrong? Did it hit where you expected? Do you need to adjust your scope, aim, rest, ammo, clothing, bench, or whatever? Or are you ready to take the next shot? Adjust what you have to.

Train as you desire to be able to shoot. Start simple, gain confidence in your equipment and know what it can and cannot do, then work your way up. The following is a possible dialog and events between a shooter(S) and his coach(C)/spotter on a trip to the range.

C “Spotter ready. Light wind from the right. Maybe three mph.”

S “OK. Holding dead center.”

C “Send it.”

Bang! The shooters head pops up like a prairie dog. He squints at the target. He carefully ejects the brass and puts it in the box, picking up the next one.

C “Good trace. What happened?”

S “Oh. my fault.”

C “So… what happened?”

S “Jerked the trigger. Broke right a ways.”

C “Right? You hit left. 9 o’clock on the 8-ring. Try it again, no adjustment. Wind’s the same.”

S “OK.” He loads up and settles down behind the rifle, adjusting the rest under the forestock and the small sandbag underneath the buttstock. The spotter watches the shooter, the line, the wind, with both eyes open and relaxed.

C “Remember to follow through.” There is a long pause for final breathing and focus.

S “Ready.” The coach / spotter settles in behind the 40x spotting scope and gets a clear image of the target and the slightly wavering summer air.

C “Spotter ready. Send it.”

BANG! No prairie-dogging this time. Good.

S “Clean break, dead center.”

C “Hit 9 o’clock, 7 ring. Wind kicked up a bit just before you fired. Same thing again.”

S “Can do.” He reloads, fiddles a moment, settles down. “Shooter ready.”

C “Wind’s up more from the right. Hold and inch right.”

S “Holding an inch right.” BANG! “Clean break, inch right.”

C “Looks like another at 9 o’clock, 7 ring. Might have to adjust the scope.”

S “Oh yeah. Last time I was at the Puma range with Fred we had a heck of a wind from the left. Steady twelve to fifteen. Got to take that off the scope.”

C “Did you have that in your notes?”

S “Crap. No, figured I’d just remember it.”

C “That’s why we take notes. Take it off, and add… oh, about an extra two inches. Puma’s two thousand feet lower. And make a note of it.”

The shooter makes the adjustment, and scribbles down a couple of notes, thinks a bit and adds a few more words. “Up to nearly 1400 rounds on this barrel.”

C “Got a while still before you can shoot better than it can, though. At least another six hundred.”

S “More like ten thousand six hundred at this rate.”

After working together that way until the shooter gets a pair of solid four shot groups on the point of aim (it takes another twenty rounds), they switch off and do the same again to “settle in” the other man and let the first barrel cool. Not letting the barrel get too hot helps improve accuracy and extends barrel life.

Part way through, they remembered to put on sunscreen and take a drink of water.

Once they are both comfy and making respectable groups on paper with a good rest (meaning they KNOW the rifle and ammo they are using are in perfect working order), they compare the targets with a couple of older targets that had notes on them, and decide that this brand of ammo appeared to be shooting a better group in one gun, and a worse group in the other. Food for thought at the next ammo purchase, or when they started reloading.

They then switched to a closer target, shooting from classic field supported positions: cross legged (elbows on knees), prone (with and without an ammo-box rest, and kneeling (one elbow on one knee, with a little cheat of leaning against the range roof support beam), practicing for twenty round in each position in groups of five (shot slowly), switching between each set to relax and let barrels cool.

They took a couple of short breaks to chat with neighbors, see what sort of hardware and ammo they had, offer an observation, loan a sheet of paper and pencil to a newbie, admire an old 1898 Mauser in beautiful condition that shot passable groups, talk about training opportunities, and relax their eyes and backs (not quite as young as they used to be).

They shot their final 15 rounds from the bench, going for a fast shot with two follow-up shots and a reload as quickly as possible, then getting back on target for a “possible fourth shot.” Each string was followed by a quick self-critique and observations by the coach. Then a bit of clean-up, brass collection, police call to make sure they left no garbage or equipment, and final note-taking while it was fresh in their minds. A proper notebook would be nice, and a reminder to follow-through and talk more clearly about what happened when he pulled the trigger. They both still needed improvement at doping the wind, but the trigger-squeeze was getting better. And neither of them scoped himself at all, so that was a plus.

That is what some quality practice might look like.

That is not what hunting looks like. You can do a pushup or twenty, right? How well can you shoot after running fifty yards, climbing an embankment, scrabbling through the brush, and pulling your pack past the barb-wire fence to get that shot at… 120, 150, 210 yards?

Hunting also requires you be in reasonable physical shape… speaking of which, pull out your calendar. Now would be a great time to schedule a workout, and check your email to see if your buddy can make the shooting range date you scheduled.

Happy shooting!

Precision Shooting

5 Comments

Leave a Reply

Latest from Culture

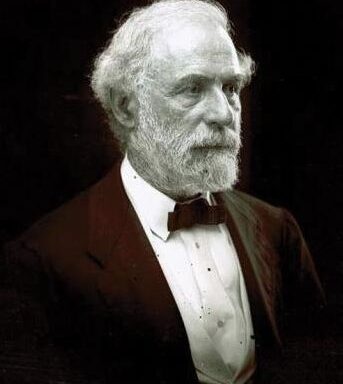

A Memory of Robert E. Lee

"Everyone obeyed him, not because they feared but because they loved him."

The Venerable Bede

"Arising from the gloom of a dark age, he is still considered one of the most illustrious of the learned men of England."

Gildas

The underrated chronicler who paints "fully and vividly the thought and feeling of Britain in the fifty years of peace which preceded her final overthrow."

Movie Review: The Thing (1982)

A brilliant horror movie that blends the right amount of suspense, schlock, body horror, and practical effects to create a classic.

Friday Music: September 87 – Room Service

Editor’s note: See the previous chapters at these links: Bad Dream Baby and Light Years.

Good stuff. There’s nothing like hearing the steel ring after a hit at 500 yards or farther.

I highly recommend Project Appleseed for an intro to basic rifle marksmanship. They teach to a 4 MOA standard (man size target at 500 yards) from prone with nothing but a rack grade rifle, iron sights and sling. They hold hundreds of shoots a year all over the country. It’s a great foundation for precision shooting.

3.5

5

I am a hunter. Mostly for deer and hogs. And, any other varmint I can see. My favored rifle is a BAR .270. I keep my Leupold scope sighted at 150 yds. I prefer neck shots.

If it’s beyond 150, I’ll go for the shoulder shot.

Great post! Have nice day ! 🙂 9oabd